The many superfluous and agitated conversations one has the chance to be witness to if one holds even the mildest of interests in the pizzazz and glamour of the Academy Awards cannot be, in any overt manifestation, nimbly recounted. It’s a mirage of insightful observations and a scintillating parley of the innumerable foibles of the Academy membership that, from the perspective of one possessing proximity to said tête-à-tête would reveal to be little more than a congregation of fanatics seeking complacency in their self-aggrandizing and largely ill-informed opinions.

The internet has turned this into an unceasing multitude of amusement respites, from frivolously crafted opinion pieces filled with witty soundbites to the notorious advent of the meme culture. And it succeeds in its grail thanks to its ability to incite in us an empathy for the underdog. Envision a situation where DiCaprio had won the Oscar in ’93 for ‘What’s Eating Gilbert Grape?’. Do you see, in that hypothesis, all the attention his citations for ‘The Wolf of Wall Street’ or ‘The Revenant’ garnered?

And yet, with the inception of every awards season, our unfailing obsession over the Oscars begins to hound us. When the nominations are announced, they surpass even the slightest shred of restraint and elucidate themselves in expressions of either boundless exuberance or conspicuous vexation, much to the chagrin of our ménage and peers.

But were any justification to be found in this rather inconsequential palaver, it would be that some of the Academy’s many decorations are too inequitable to compensate for the various meritorious candidates that were erroneously omitted from consideration. If a member of the audience, smitten by the prestige the Oscars command, decided to watch the best films of the 1960s, it would be trivial to point out that he might skip ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, the impossibly avant-grade classic that wasn’t up for Best Picture in the year of its release, and might have to endure the insipidity of ‘Oliver!’, the winner of the category that year.

So with the intention of preventing a legion of moviegoers from being denied the field day of discovering artistic brilliance disregarded by the Oscars, these are the performances, ranked in order of their efficacy, that vindicate all of the movie enthusiasts who grumble and disapprove when a worthy choice is looked over for lesser alternatives:

15. Jim Carrey, ‘The Truman Show’ (1998)

Aside from the apparent peculiarity and discerning inventiveness of the rendering that landed ‘The Truman Show’ nominations for Best Director and Best Supporting Actor (for the incisive performance from Ed Harris that seems to perfectly concur with the societal commentary implicit to the film’s striking ability to prognosticate the dreary future of reality television), one of the film’s most humongous achievements was to expend Jim Carrey’s disposition towards serious acting and not the marginally off-putting, and customarily gauche clowning he so often sanctions himself to be a victim of. Instead, ‘The Truman Show’ builds to a searing rendezvous of his contrasting yet oft-unavowed capacities of both a stupendous comic actor with inordinate comic timing and a dramatic character actor brimming with observable and serene humanity.

14. Julie Delpy, ‘Before Sunset’ (2004)

Richard Linklater’s ostensibly implausible saga of the anatomy of human conversation is an unmatched odyssey of mortal affinities channeled with such pathos and humor that it’s quite hard to describe the singularly towering work of Julie Delpy, who, in my most unprejudiced opinion, steals every ‘Before’ film from Ethan Hawke. It’s the air of irreverence, that unbridled spark of independence, that holds such immaculate allure to her Céline. There is a nearly latent, affecting sense of despondency in her eyes as she contemplates the many opportunities of a more joyful life now perished and an incandescent reinvention in the expression of joy at the plethora of possibilities that still await her. It’s akin to watching a photo album featuring variegated, fleeting memories that we seem to have lost the faculty to behold and look at with necessary relish.

13. Björk, ‘Dancer in the Dark’ (2000)

Danish filmmaker Lars Von Trier probably does not think of cinema as a medium of escapism in the basest of senses. The intellectual exploration of somewhat inscrutable ideas that form the very kernel of his decidedly controversial films can lead to equal amounts of intrigue and repulsion. ‘Dancer in the Dark’, a film whose current marketing strategy exploits the very magnitude of its critical polarity, is a textbook case of a Von Trier film being horrendously hated and deferentially beloved. And while I vote with those who disparage its stark dose of maudlin, the depth in a performance so accessibly heart-wrenching and forthright in its rendering of the ugliness of its subject’s predicament just cannot be misprized. But it was.

12. Marcello Mastroianni, ‘La Dolce Vita’ (1960)

The banal heed an average moviegoer pays to the visionary, cinematic interpretation of a certain way of life would never suffice if one were to seek the true bliss of ‘La Dolce Vita’. What would the iconic scene in the fountain mean to him? What would the inescapable enticement of the shoddy profession of entertainment journalism signify? What would Nino Rota’s exalted score bring to his consciousness? What part of Marcello Mastroianni’s understated, utterly bewitching, resplendent performance, attuned to Fellini’s vision, void of any irregularity, lead to retrospection, soul-searching, even? Wouldn’t he dismiss this as a mere probe into the art of neo-realism Fellini is celebrated for? Maybe he will. My estimation of his misfortune cannot be overstated.

11. Bill Murray, ‘Groundhog Day’ (1993)

The modus operandi of our quotidian lives is so excruciatingly prosaic that Phil Conners’s peripheral cynicism seems to be rather sagacious. Slogging away in a job that, in its inconsequentiality, is in no accord with his ambitions, self-loathing forms the genesis of forced cheekiness and impertinent humor in his interactions with the world around him. A clock ticks on one fateful Groundhog Day, and Conners is bestowed with the benefaction of a forever, which he initially greets with sparse amusement, which swiftly transmutes into utter perturbation and then evinces signs of self-immolation desires, before it’s incontestable to Conners what it was always intended to be: an opportunity to try. After all, as an ameliorate Conners would have us know, “When Chekhov saw the long winter, he saw a winter bleak and dark and bereft of hope. Yet we know that winter is just another step in the cycle of life. But standing here among the people of Punxsutawney and basking in the warmth of their hearths and hearts, I couldn’t imagine a better fate than a long and lustrous winter.” Maybe there’s no tomorrow and the childish search for a new day will always one day surcease to become the adult accession to the same old, but Murray and his dignified perspicacity is infectious as is his tenderness gladsome.

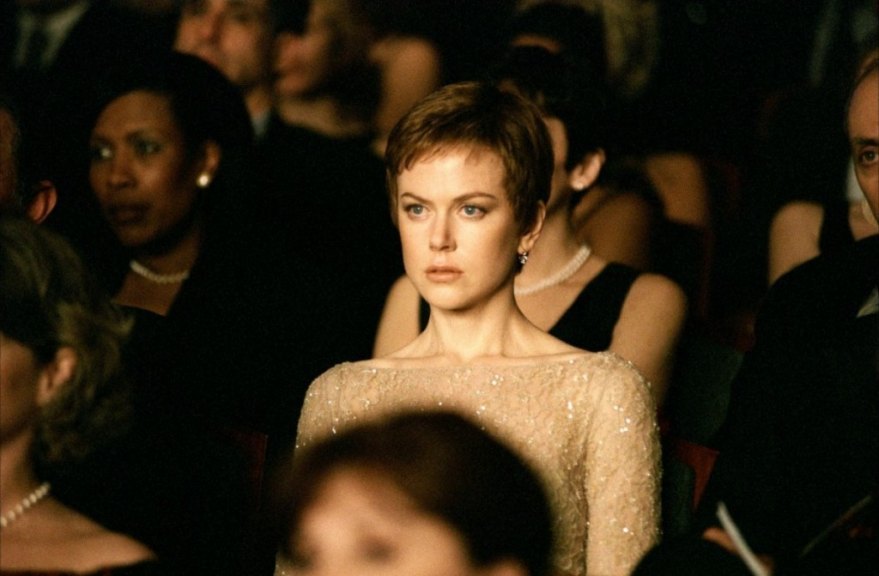

10. Nicole Kidman, ‘Birth’ (2004)

Our insatiable propinquity to the dead is characterized, more often than not, by our underestimation of our own solitude. As Kidman’s Anna acutely contemplates her maddening acceptance of the 10-year-old claimant of the identity of her departed consort, her face flickers with fervent trepidation, as if falling into a bottomless pit as the harrowing opera she’s audience too blazes on to consume her entirely. The infinity of detail to delve into in that single sequence would be abundant in its quantum for a fully disparate analysis, but Kidman’s forlorn sadness, exhibited with such balletic finesse, will corroborate with anyone incriminating the Academy for not being adequately risqué.

9. Al Pacino, ‘Scarface’ (1983)

The grand canvass of the cinematic career of Al Pacino is too enigmatic and colossal to decipher using the rudimentary wealth of words. He’s been handsomely quiet and grotesquely bombastic, strikingly tender and repulsively garish. In this rather misconstrued and confounding crime drama, Pacino employs his most efficacious performing tool: authenticity. There’s no ounce of superficiality in that arresting and expressive face, each layer built on nothing but the sincerest veracity. A Cuban immigrant turned drug kingpin, the absence of a proclivity towards the crime-drama staple of character arcs is what makes this film and this performance so deliberately incongruous.

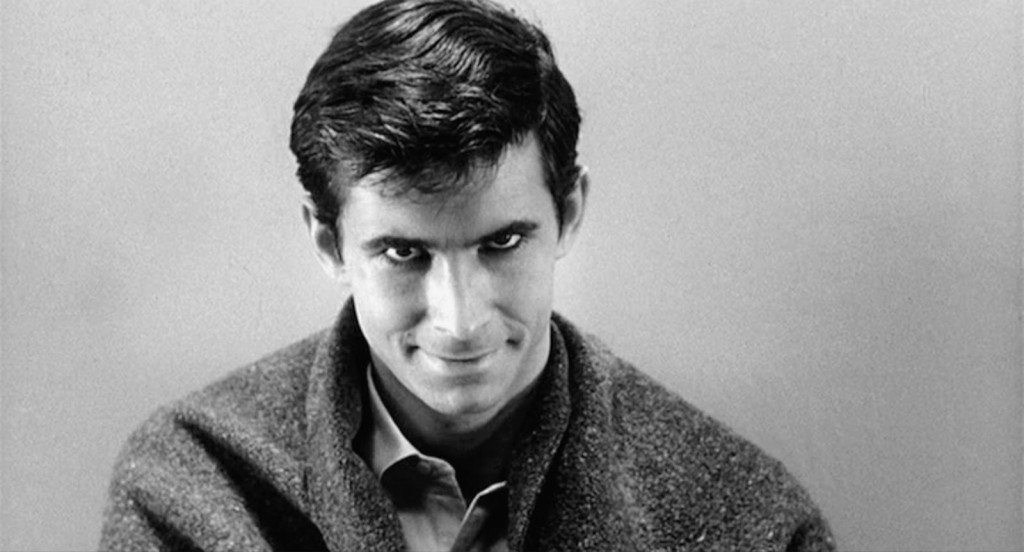

8. Anthony Perkins, ‘Psycho’ (1960)

My very first experience with Hitchcock’s masterpiece was one where the proceedings haunted me in a way that defined my palate for the horror genre. If it wasn’t Psycho good, it wasn’t worth it. An essential, cardinal part of that predisposition was Norman Bates’s superlative characterization by Anthony Perkins. A man too normal to be hackneyed, too much of a simpleton to be a comfortable presence to be around. And assuredly, Janet Leigh’s Marion cannot help but feel the unease when she first espies a slightly unhinged soul staring at her behind that deceiving facade. It’s not so much the suspense that make for a spectacular climax, but the viewer’s speculation of the provocation of Norman’s descent into madness, which Hitchcock and Bates, with such intoxicating hypnosis, let run wild.

7. Dennis Hopper, ‘Blue Velvet’ (1986)

Ever been on a reckless spree with people you don’t exactly trust, but compel yourself, snubbing all coyness and insecurity threatening to implode in your chest, to continue down the heedless venture? And then there comes a moment where one of your unscrupulous companions threatens to precipitate a tornado of your very worst insecurities, coercing you to contemplate consequences that horrify you to your very marrow. Dennis Hopper played the gas-inhaling, sadomasochism-inflicting, suave-men-loving, petrifying and recognizable monster who believes in writing cataclysmic love letters to his enemies and hurting his victims while swaying to Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams”, is the textbook definition of that one guy in David Lynch’s surrealistic ‘Blue Velvet’. It remains unclear how much of that night would continue to haunt Kyle MacLachlan’s unassuming, troubled Jeffrey Beaumont, but Frank Booth will always be in my dreams.

6. Mia Farrow, ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ (1968)

Paranoia is seductive monster. Your deepest predilections pull you in, just as a constantly pragmatic subconscious tries to suggest the implausibility of your presuppositions. As we stare into Rosemary’s pusillanimous and gradual destruction of her own joyful, mildly blithe spirit, Roman Polanski manages to elicit a response from his audience so entirely full of fear for her, even as a cloud of mystery starts shrouding her very being. A mystifying portrayal, marked by a certain off-kilter aura that is widely adjudged to be the reason behind Farrow’s casting, it moves past the ranks of platitudinous 1960s thriller queens, to be a perceptible, harrowing part of your experience.

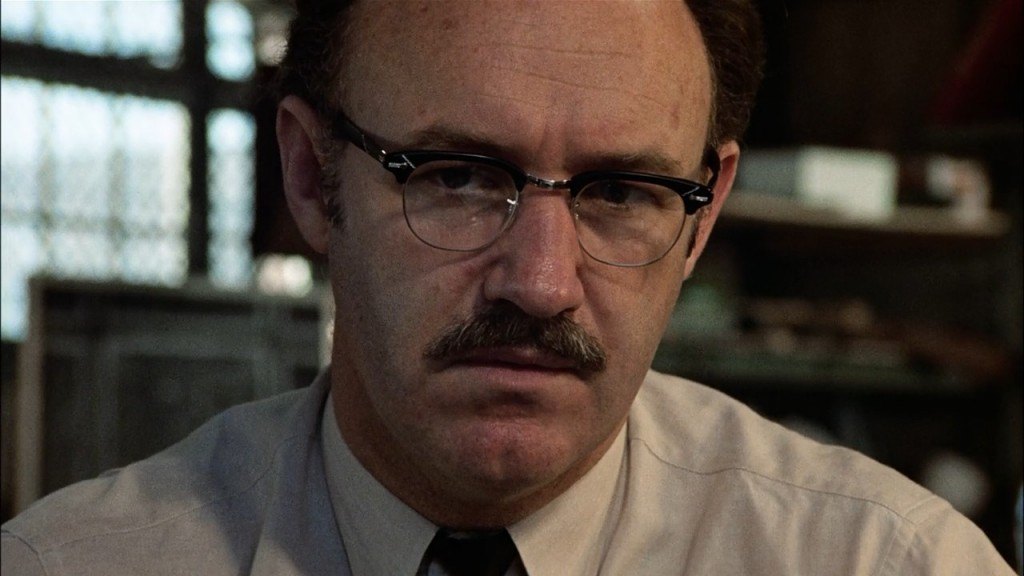

5. Gene Hackman, ‘The Conversation’ (1974)

Weltschmerz is not inherent to a pragmatic man. But the world we live in constantly drives even the most sanguine among us to be cautious of every step we take, every infinitesimal turn off the impregnable path. A distrait viewer might find Hackman’s Harry Caul to be aloof, introvert and even a social deviant. But personally, it’s that desire of our protagonist to bask in his isolation that enthralled me to his unnerving quiet. A surveillance expert tasked with listening to conversations of individuals so alien to him, the ramifications of his profession, just as alien to him, plague him to an extent where he begins to apprehend his own security. Would he ever be comforted? If that were a foreseeable reality, he wouldn’t be so ardently relatable.

4. Jack Nicholson, ‘The Shining’ (1980)

Frank Capra said, “There are no rules in film-making, only sins. And the cardinal sin is dullness.” With an obscure, cabbalistic hypnosis achieved by Jack Nicholson’s telling of Jack Torrance’s expeditious plummet into lunacy, Stanley Kubrick could’ve never found himself in the realm of that cardinal sin so many of those sophomoric artists do. Many believe, including “The Shining” author Stephen King, who despises the film, that Nicholson’s performance is nothing more than grandiloquent. But the coldness of his convictions and the anonymity of his motivations, Jack Torrance, a typical Kubrickian creation, a product of his detached approach to movie-making, manages to elevate the effectiveness of Kubrick’s inimitable knack at atmospheric cinema to a level only the scene with Jack and Charles Grady in that vividly red restroom can perfectly elucidate.

3. Ingrid Bergman, ‘Casablanca’ (1942)

Radiating gob-smacking beauty of both body and spirit, with that nonpareil voice that emanates anguish like little else in the world, Bergman’s Ilsa Lund was destined to be the paragon of all romantic heroines. Sharing divinely understated chemistry with co-star Humphrey Bogart, she captured the essence of a women’s profound comprehension of the erosion of the past accelerated by war. A motion picture frequently attributed with the induction of war romances in cinema is sans all pulchritude, all sublimity, all depth, were it not for Bergman, euphoniously asking Sam to play “As Time Goes By”.

2. Malcolm McDowell, ‘A Clockwork Orange’ (1971)

Lest we not forget that a future so atrociously dystopian could be in plain sight, lest we not err in our estimation of the rectitude of society’s power-wielding individuals, and lest we not relish monstrosity in it’s most unsavory apparition, Kubrick wanted us to be privy to all of those in his resplendent, punk, unorthodox masterpiece. At the center of this radical vision was Malcolm Macdowell’s Alex DeLarge, a vicious teenager with amorality running in his blood and a sempiternal love for anarchy. McDowell’s eyes betray his insouciance for the piece’s importance and it works to lend Alex and the world he occupies a gravely somber undertone, driving in the point that in an increasingly perfunctory world, a man without a choice is not a man.

1. Naomi Watts, ‘Mulholland Drive’ (2001)

Ah, no one smiles like that Betty. From our very preliminary encounter with Watts’s saccharine, downright ingénue-esque, personification of navieté, Betty Elms, our guard is off. She’s superlatively lovable, but also bewilderingly labyrinthine. Her other incarnation, Diane Selwyn, is crafted in absolute divergence from Elms: dark, desolate and certifiably manic. As the film glides over dream and reality, with no portent to where the narrative might go from a certain point, Watt’s performance ratchets up a storm of cinematic brilliance, all of it climaxing in that one audition sequence where all of Lynch’s anomalous delirium collectively seems to transcend the very medium of cinema. Is this the girl? You bet.

Read More: Best Thrillers of All Time