The genius of A Clockwork Orange (1971), arguably, the greatest film Stanley Kubrick ever directed, is that today, forty four years later it still feels futuristic, the future depicted within the film still feels possible. As other futuristic films have aged, time eroding their vision of what might come, A Clockwork Orange (1971) remains as timely, as urgent as ever.

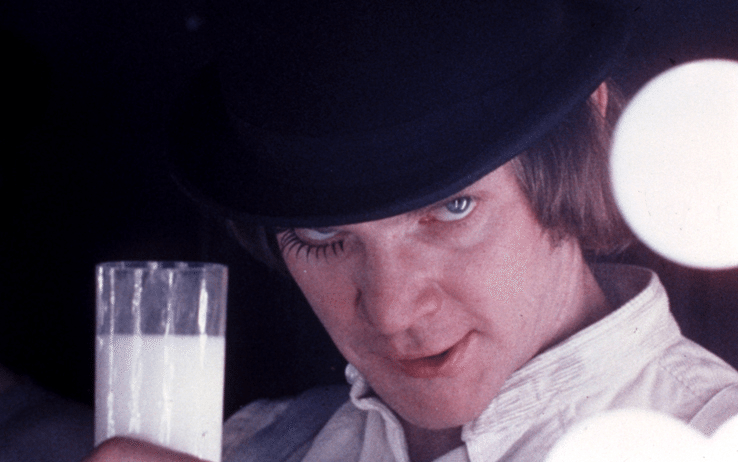

It is not an easy film to watch, darkly brilliant, vicious, yet with moments you cannot look away from the screen, akin to a car wreck. There are moments of perversity, comedy and chilling, cold blooded violence, yet the jaunty manner of the film and Malcolm MacDowell’s brilliant upbeat performance keeps us interested in the film throughout. It is a profoundly brilliant performance in that despite his horrific acts, we cannot help but like him, root for him and be horrified when he is used as part of a mind control experiment that takes away his free will.

A Clockwork Orange (1971) is set in the near future of Britain, where it looks and seems as though some sort of Communist society is governing. Without question it is a dystopian crime thriller that will ask many moral questions and attempt to answer them through what happens with Alex. He is a thug, nothing more than a common criminal, a sociopath delinquent whose primary interests include Beethoven, rape, fighting, violence of any kind, criminal behavior of any kind and what he calls the old unltra violence, which is violence ramped up by drink. He steals routinely, does what he pleases when he wants.

The film explores a crime spree he and his Droogs carry on, one in which they burst into the home of a writer and his wife, rape her, and beat the old man until he is paralyzed and left in a wheelchair. This sequence contains one of the films most chilling scenes, as Alex is preparing the woman for the rape that is to come, he bursts into a song and dance, crooning Singin in the Rain as he punctuates each stanza with a punch, a kick, or a beating from his cane. It is an alarming sequence, like a car wreck from which you want to look away but cannot. Their night ends with a fight with Billy Boy and his own thugs, interrupting a rape they are going to perform on a young woman, and then Alex returns home to sleep. The next night they go out again, but his Droogs are unhappy with his leadership and betray him, and after he kills a woman, they smash a milk bottle in his face allowing the police to capture him.

Sent to prison, Alex wants to reform, we think and volunteers for a mind control program that will drive thoughts or actions of any sort of violence from him. The problem is that as he watches the images unfold before him and becomes increasingly ill, he also develops an aversion to his beloved Beethoven, which is the music playing behind the images. Thus when he finishes the treatment and is ready to be a productive member of society, he becomes violently ill at the very thought of rape, violence of any kind, and upon hearing Beethoven. His freedom of choice has been taken away. His nightmare continues when he encounters a group of old homeless men he used to terrorize, his Droogs now police men beat him senseless, and he arrives at the home of the writer he made paralyzed, whose wife has died, and who is fixated on revenge. The old man takes him in, not recognizing him, cares for him feed him, and offers him a warm bath, and it is in that bath that Alex betrays himself, singing Singin in the Rain as he soaks, the old man outside the door listening. They lock Alex in the attic and begin playing Beethoven to drive him mad, driving him to attempt suicide.

He is now a sort of hero, a victim of government mind control, and a sensation. The government owes him, and has no idea the thoughts in Alexs mind are of rape, murder and mayhem. He was back all right.

Beyond the startling performance of the gifted Malcolm MacDowell, who never did anything remotely close to this brilliant again, we have Kubricks direction, which is audacious and bold. His camera seems to be always moving, bringing an energy to the film that is like the MacDowell performance, buoyant and jubilant.

Here was a film about moral choice, that actually suggested it was better for a criminal to make their own choices, however wrong they might be than to be controlled by an Orwellian government who saw all and knew all. The film is dramatic no question, but also a black comedy, as dark as they come, and executed with genius by the director. Slapped with a X rating in the United States, it won the New York Film Critics Award for Best Film and Best Director, and despite howls of protest was nominated for four Academy Awards including Best Picture and Best Director. But of course the Academy would never honor a film like this, its real reward were the nominations I suppose.

Its greater reward is that time has had no impact on the film, it remains as topical as it was forty four years ago, and there are very few films that can lay claim to that. A dark, troubling work of art.

You must be logged in to post a comment.