Long takes or shots as a trend has recently seen an irritating amount of exploitation for the sake of acclaim since there seems to be an assumption that longer takes are more impressive by nature than a well-edited sequence of short shots. The list below is populated by just six directors because drawing the most out of an extended take often requires a huge amount of patience, artistry, and technical skill. The people behind these impressive feats of cinema often incorporate them into their visual language and, as a result, go on to consistently produce exceptional long takes — some might say the very best.

Whilst I won’t deny the choices below favor certain artists, I also think it’s undeniable that their careful deployment of the long-take method fully deserves being honored once, twice and maybe even three times on the list below.

10. Apocalypse Now – The End

The eerie beat of propeller blades cuts swathes through the darkness Coppola begins on and then we fade onto a jungle, bushes and brush occasionally offset by little gusts of wind as helicopters swoop by and little jets of yellow smoke signal the arrival of an inescapable doom. Its genius. Brief, beautifully shot and masterfully directed by the much-revered Francis Ford Coppola; this tiny fragment of ‘Apocalypse Now’ might be the finest thing he ever put on a screen. Wonderful.

9. Sátántangó – Sunrise

Belá Tarr crafted his 450 minute magnum opus Sátántangó through the use of only around 150 long take shots and whilst his deeply effective first scene just barely missed my Top 10 Opening Scenes list there is no way this indelible achievement of the medium is going to lose out here.

The shot itself is simple: Just a sunrise. Yet take a look at what it means in the context of the world-building Tarr is attempting to achieve and the focus on feeling over thought that he foregrounds in the form of his film-making, and you have a brief run of inescapable wonder as a pitch-black room is gradually filled with light. Such an ingenious visual device with which to kick-start the story of the film.

8. The Thin Red Line – Letter

After quite literally several hours of dread-imbued carnage, seeing countless brothers in arms torn to shreds by unending hails of machine gun fire, Terrence Malick finally settles down and brings us up to date with one of his many characters: A man whom has been gifted with beautiful visions of his distant lover that served as some solace amidst the hellish combat he was exposed to. Malick’s brief dives into this man’s past at home are gorgeously photographed, intimate and refreshingly plain: Free of intercutting with nature or spatters of blood. Honest. Heartfelt.

Then the platoon’s mail comes through and this man, after everything, reads the note that banishes the woman he loves from his mind. He took too long. She found someone else. Actor S does absolutely astounding work in selling the denial, anger, bargaining, depression and final, haunting acceptance in an utterly tragic microcosm of grief that Malick masterfully chooses to handle in a single take- and from an observer’s distance to almost impart some shame onto the audience for not leaving this poor, poor soul alone to weep for his loss.

7. The White Ribbon – Sawmill

Whilst the agonising take from ‘Funny Games’ where two parents reel from the death of their child for 10 straight minutes is a horrifying sight, I think Haneke’s work in ‘The White Ribbon’ where a man stumbles into a ramshackle little room to find the mutilated corpse of his wife is even more moving. There is something about the angle he captures it from: Positioned just around the corner of a wall so that we see the bed she lies on but can only imagine the horror of her face after a deadly accident at the sawmill.

It’s a moment that despite our prior lack of time spent with either of these characters is as painfully evocative as having sat there with the woman you adore for a lifetime — and then have to sit there again and watch the life that used to wash through her be totally absent from the lifeless body that remains. Exactly. Silent, torturous and incomparably moving.

6. The Third Man – Ignored

The final shot of Carol Reed’s pitch-perfect masterwork sees Anita Valli icily ignore the helping hand of Joseph Cotten, walking from a huge distance in one of the most incredible, well-framed and limitlessly ambitious shots ever mounted. Like the rest of the film it’s an impeccable practice in every form of the craft — even down to Anton Karas twanging away the final few notes of the movie’s minimalist Zither score. Stunning.

5. Stalker – The Rules

I can’t deny the fact that there is no master of long take shots more adept in their art than Andrei Tarkovsky. Modern auteurs like Alfonso Cuarón do sterling work in the likes of ‘Children of Men’ and especially ‘Gravity’ but I can’t help but in part fill the latter half of this list with sequences from the great Russian master.

And starting us off at 5 few moments from ‘Stalker’ are as hauntingly powerful as that in which the titular Stalker explains the deadly forces that sweep throughout the zone and the respect that they are due: Giving a frenzied and genuinely frightened performance under the steady gaze of Tarkovsky’s up-close lens that effectively sells the terrifying magic such a place can bring to bear.

The icing on the chemical-infused cake here is the final pan away from the stalker’s face over to Writer and Professor — who turn to “The Room” in awe. When we began the shot it stood clear as day in front of the characters but is now hidden behind an unbelievably dense sheet of icy white fog. The fact that the supernatural mist drifted in as our eyes were off the Room but more importantly all in one take speaks to a consummate technical mastery from the special effects team on the scene and makes that crowning moment all the more realistic and stunning.

4. Werckmeister Harmonies – Hospital

Violence on screen has been done every way under the sun. From the grueling 10 minute rape and beating scene from ‘Irréversible’ to quick cuts in the likes of ‘The Bourne Ultimatum’, few directors can come up with a truly original take on human brutality.

Hungarian genius Belá Tarr not only does something unique but morally profound. In a 7 minute long drifting take through a hospital, his violence does not motivate in any way other than disgust. Distinctive realism in punches and kicks achieved through misses, soft blows and an occasional horrifying hard crack on the head lends a naturalism to the sequence that subverts the clearly simulated world on show in this highly controlled long shot and allows us to connect with the characters on-screen, rather than the technique behind it. Unexplained and unfathomably disquieting, it’s a mesmerizing piece of movie-making anyone with access to the DVD should go out of their way to see.

3. Nostalghia – Candle

The second Tarkovsky, ‘Nostalghia’s protracted conclusion watches the main character, Andrei, walk across an ancient bathing pool that has long since lost its water. It’s difficult to describe the effects and connotations of the sequence without everyone reading having seen the film and perhaps even more difficult if you do watch it; because ‘Nostalghia’ is a deeply personal piece of work that appeals to the mind of the individual rather than sweeping waves of feeling through the masses.

All I can say is that Tarkovsky’s patient pace and unwavering focus on Andrei makes a conceptually dull piece of cinema fly by in a heartbeat and, in the end, leave us with as profound and crucial a message as the artist may have ever left us. In short: Get watching.

2. Irréversible – Hope

Gaspar Noé’s divisive 2002 masterpiece follows the rape and apparent “revenge” of a woman, except shot in reverse — a narrative choice directly inspired by ‘Memento’. In doing this, we contemplate the consequences of the revenge long before we understand what it is about and thus are faced with a uniquely difficult experience in navigating Noé’s labyrinthine hellscape of swirling cameras and the hungry jaws of brutality flashing their teeth around every corner.

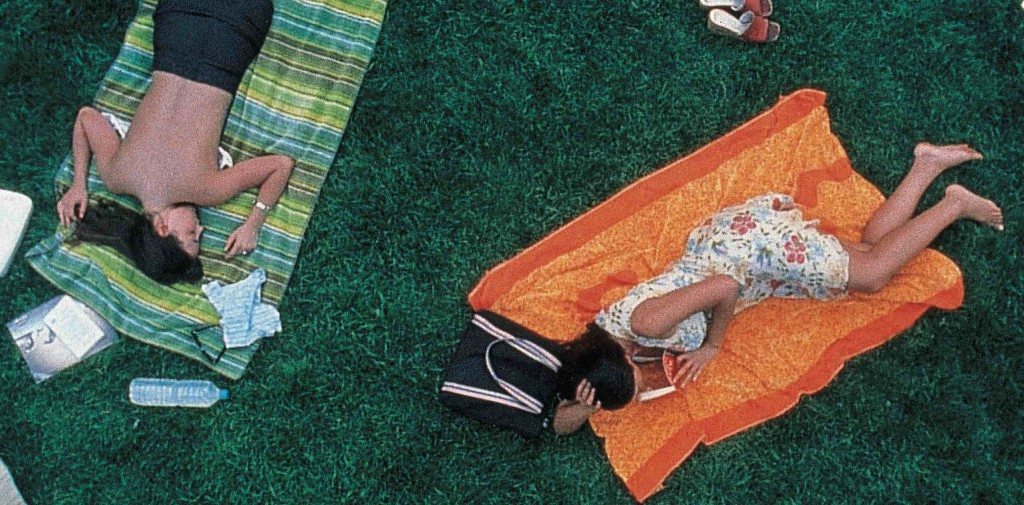

But what marks the piece out as something special for me is the second half, in which the narrative becomes technically inconsequential to the plot of the movie and yet does wonders in fleshing out the people to which this tragedy is about to befall. They go about their lives wearing smiles and unknowingly acting out haunting preludes to the nightmare to come — all culminating in a 3 minute take whereby Noé drifts out of the girl Alex’s window and down to her, earlier in the day, watching children play in a park.

A subtly ominous symphony blasts in the background as we witness the woman dream about the pleasure childbirth might bring her. All the laughter and grinning and playfulness that those bundles of joy might bring and how it could take it all- everything- and enrichen her life beyond measure. Hope, shimmering beautifully against the grim darkness of the human condition that seeks to encircle and destroy her. As Noé’s final words preach: “Time Destroys All Things”- and yet I can’t help but be taken away by the overwhelming sense of simple joy that flows through this scene.

1. The Mirror – Fire

There is quite literally nothing to say here. I could go on about the beauty of the sequence, of Tarkovsky’s perfect pacing, sound design, composition and application of practical effects. Every discipline of the silver screen is practiced here at its absolute zenith and yet that might be the exact reason why the Fire from ‘Mirror’ is so special: You don’t notice any of it. Despite all of this technical wizardry, you can’t help but become totally lost in the wordless wonder of the moment. The shining peak of Pure cinema.

Read More: All Andrei Tarkovsky Movies, Ranked

You must be logged in to post a comment.