A vivid, ever evolving association with Stanley Kubrick’s cinema may not always stem from an authoritative, ingenious work of acting. Filmmakers of Kubrick’s kin believe more in exploring ideas and intuitions based on evidences more imagined than analysed. The culture has long since accepted their accomplishments to be more in discovering newfangled means of subconscious transportation to destinations widely unplumbed than in indulging in iconographic, voluble recitals of banal schmaltz. Famously quipping, “Cinema is not photographing reality, it’s photographing the photograph of reality.”, Kubrick’s contentiously diverse oeuvre appears to unfledged eyes as deliberate alienation with a disturbing regularity.

What one may make of the use of music, or the playfully many-leveled, lissom editing in ‘A Clockwork Orange’ contrasting crisply with the sluggish, nearly sedate one in ‘Barry Lyndon’, both exhilarating atmospheric contrivances, or even of the anesthetizing visual ostentation, is at first unbeknownst to one’s own self. Time is of great assistance with cinema of this breed and memory perhaps the most reliable auxiliary. Float the images in your head and a lasting faculty of impressions is found to be at work.

Kubrick didn’t possess a marked propinquity towards most of his actors. It is evident from his stately precipitation of complete, unqualified hegemony exercised by him in nearly all the films he made. The man famously drove Shelley Duvall to frequent instances of ill-health during the protracted production, a feature common to nearly all his films post ‘Dr. Strangelove’. Malcolm McDowell once shared exuberantly his recollections from his time on ‘A Clockwork Orange’, but offered in conclusion an absurd detail: Kubrick refused to take his calls when the film was in the can, dismissing the friendship as if it hadn’t transpired in the first place.

But then how did he manage to draw out some of the most memorable performances in cinematic history? The man who didn’t put requisite stock in narrative or character as he did in procuring that right alloy of sound and image nevertheless ordained in the most opulent of cinematic voices that his actors’ legacy would be inextricably intertwined with his masterpieces. So electing the most magnificent performances from his filmography didn’t prove to be as much of a quest as ranking them did, purely for the fact that they all work for varying reasons and are part of such varying films.

So with that, these are the 10 greatest film performances in the films of Stanley Kubrick, ranked in order of their success in being the tools at his disposal, because frankly, they should’ve never hoped to be anything more.

10. Peter Sellers, ‘Lolita’

Sellers had an unimpeachable aura of sublime intelligence etched into his very being. Playing the delectably over-the-top playwright Clare Quilty, he injects a consciously out-of-control edginess to the film, which is hard to accomplish in one about the infatuation a man in his 40s harbors for a teenage girl. The film’s footing remains as one Kubrick’s weaker works, but Sellers’s infectious double whammy of disastrous silliness and ironic self-seriousness is what secures ‘Lolita’s’ place in Kubrick’s enviable lists of opuses as one of his most original.

9. George C. Scott, ‘Dr. Strangelove’

An ever-notable stimulus for political black comedies from across the globe, ‘Dr. Strangelove’ fully established Kubrick’s celebrity among the section of population so lovingly deemed ‘hip’ by their not-so-hip counterparts. And the impudent spirit of the film is primarily defined by actors given full leeway so long as their antics were unorthodox enough for the filmmaker’s camera. George C. Scott’s General Buck Turgidson is the definitive nightmare: goofy, eccentric and uncharacteristically perverted. And Scott plays him with such pomp, your sensibilities are contradicting at almost every moment he utters some delirious piece of insight. Also, that level of acumen at gum-chewing warrants extra points.

8. Douglas Rain, ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’

Playing what is essentially the most para-human character in what could be called an ornately cold, somber film can be onerous if you’re not afforded the facility to show, but only to speak. It gets threateningly precarious if you’re playing a computer. But Douglas Rain and his ineffaceable voice did the trick as if it were entirely perspicuous. From the very first time we hear it, it’s unmistakable that the technology it belongs to has manifested capability to be in command of faculties outside its existence. Aside from the glaring fact that all of the film’s dramatic force is pivoted around it, HAL 9000 is another addition to Kubrick’s creations of fantastical, insatiable monsters with perturbing potential of mirroring reality.

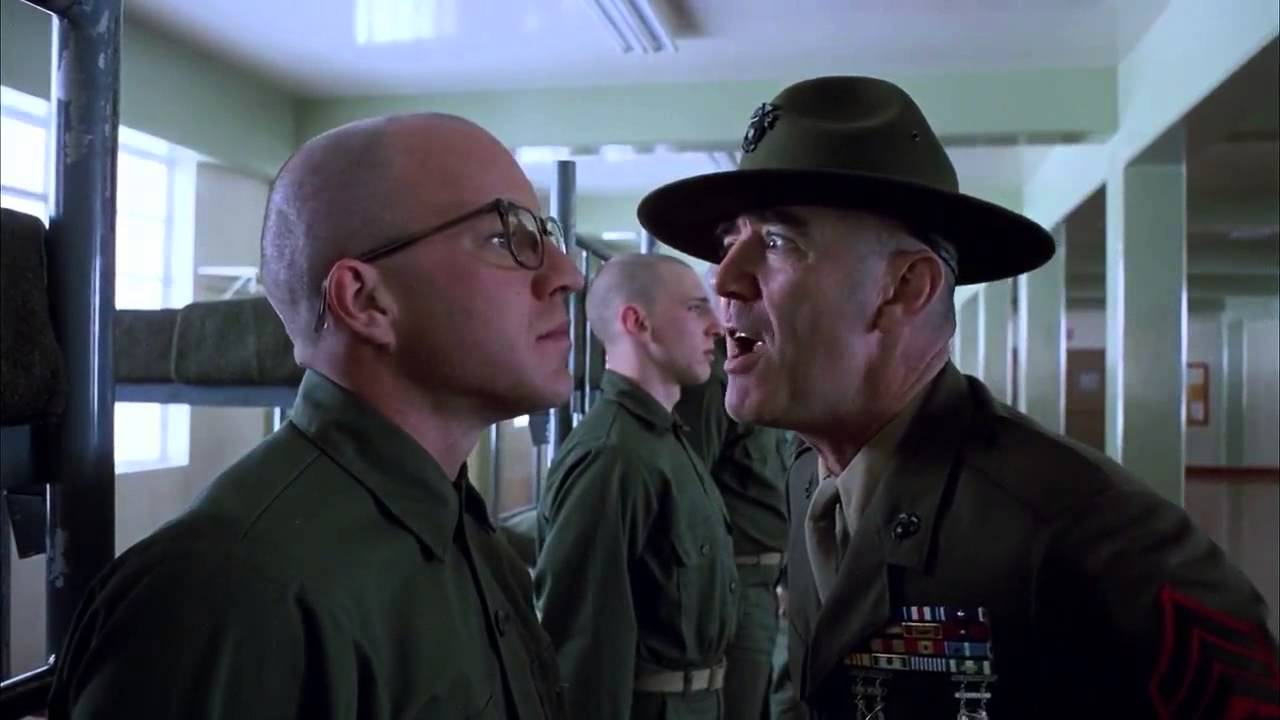

7. R. Lee Ermey, ‘Full Metal Jacket’

Keeping my personal umbrage of Mr. Ermey’s untrue contention that Kubrick had been duped into making ‘Eyes Wide Shut’ (a film beloved by your humble author) a certain way and that he was disappointed with the finished product, he gave a galvanizing realization of a sadism of nearly brutal proportions. Performers like Ermey can’t always be reliable when it comes to possessing a propensity for range, but Kubrick never fostered a real empathy for uncloaked depth in his characters, and when two-dimensionality can lead to such lavish dividends as in the case of Ermey’s demonic, and by turns sagacious and incongruous performance, does it really matter?

6. Kirk Douglas, ‘Paths of Glory’

If George C. Scott’s General Turgidson and Ermey’s Sergeant Hartman are eerily reflective of the bête noire some men become in times of war, whether it be Cold or Veitnam, Kirk Douglas’s Colonel Dax is Kubrick throwing a bone to the heroes. He would never tell the stories of heroes again, and even with this one can’t cope with painting an unadulterated heroic triumph. But ‘Paths of Glory’ finds startling, moving wherewithal in its bleakness to question and elucidate in truly poetic fashion. With the sturdy, paladin, Douglas at the center lending admirable succor to the situations, it can’t have been too exigent.

5. Ryan O’Neal, ‘Barry Lyndon’

Diverging at times from his wonted casting of bombastic performers, Kubrick sporadically exploited attractive, mannered, graceful performers, the likes of which include Douglas, O’Neal and Tom Cruise among others. O’Neal here plays the colossally flawed protagonist of William Makepeace Thackeray’s lush novel: a man so pitiably controlled by his circumstance that he never administers any sense of personal strength to all that surrounds him. The weakness registers from the very first time the camera lands on O’Neal’s resplendently divulging face, educating the audience of the character all too soon, and then blends into the ceremonious proceedings as if he’s just an ensemble of colors the painter has chosen for his painting.

4. Jack Nicholson, ‘The Shining’

Jack Nicholson firmly belongs in the category of the bombastic actor. Unsurprisingly, Stephen King, who desired a stubbornly conventional adaptation, was weary of the idea of Nicholson as the Overlook Hotel caretaker whose fervid descent into madness is the primary source of horror in his story. He felt the audiences would be conversant of something wrong inside that stiff exterior. And he was right, but toying with the audience’s expectations, Kubrick and Nicholson still manage to instill reverberating trepidation and the explosive nature of performing only makes the quieter moments enormously disconcerting.

3. Malcolm McDowell, ‘A Clockwork Orange’

McDowell was 28 when he played Kubrick’s notoriously iconic Alex DeLarge. But he plays him like a high-strung child, albeit a frighteningly and somewhat hilariously precocious, hyper-observant and devilishly playful one. We’re never told what made Alex or everything around him so repulsively warped, all of it shuttling towards catastrophe at full speed, but we buy into it because the Beethoven fan who pets snakes and call his friends his “droogs” is also dangerously endearing, and Kubrick’s painting becomes a mirror this time around.

2. Nicole Kidman, ‘Eyes Wide Shut’

It is not by accident that Alice Harford is the only female character on this list, for Kubrick never gave any of his actresses as much to sink their teeth into as he did the diaphanous Nicole Kidman. But before you adjudge him to be a misogynist, also realize that she is the only instrument he used to impart a moral lesson, thus, also making her the wisest of all his characters. She slaps her husband awake and relays to him the fable of a conscious, breathing woman full of inordinate amount of complexities. Kidman’s seductive poise compounded with breathtaking fragility works its wonders like few things in Kubrick’s majestic canon do.

1. Peter Sellers, ‘Dr. Strangelove’

And there we have it. From Peter Sellers to, well, Peter Sellers. And I can hardly complain. Sellers is the greatest comedic force cinema, a medium the analysis of which continues to dismiss the gigantic balancing-act comedy is as frivolity, has ever been privileged enough to be graced by. He strikingly plays three different men here. He was originally intended to play four, including the commander-pilot of the B-52 bomber, who was later played with generational flair by Sim Pickens. Kubrick’s idea was that Sellers be in metaphorical and literal control of all situations on display, exploring the idea of human uniformity across differing conditions. But Sellers’s magnetic timing and off-kilter absurdities still bolstered every element of the film, landing it smoothly in the legion of all-time greats.

Read More: The 10 Best Performances in Steven Spielberg’s Movies, Ranked

You must be logged in to post a comment.