French master Jean-Pierre Melville is the king of the crime film. His work is ruled by principles of confidence, control, and the mystery of silence that sees the development of rich, fascinating cinematic worlds filled with ice-cool ex-cons and ruled by a fever-pitch of tension. So, too, does this style benefit the world at war, and his quiet command has delivered some of the finest movies ever set in WWII. Regardless of the period or place, a constant is his enviable simplicity and how it is used to realize time-tested stories beautifully. The question is: How?

Silence

Perhaps the most distinct element of Melville’s method is in his preference for working without sound. Diegetic or not, Melville often leaves the ambient tracks on his films bare, allowing for a consuming quiet to fill the background of a scene. It’s a purposefully vacant style that accentuates the action through a noticeable absence of any other distraction. In this way, Melville makes his moments uniquely important in the eyes of the audience and, in turn, fuels further compulsion as we are constantly re-assured that everything on-screen is crucial.

Moreover, Melville’s command of sound allows him to in turn illuminate beautifully smooth pieces of score and make them special amidst this sea of silence. Sequences where Melville uses music, as mundane as some of them are, shimmer with cinematic vigour and prove exemplary not only for the study of sound design, but how structuring your movie around its sound can prove fruitful when handled with the same pace and purpose as directing on-screen.

A scene that personifies this mastery with a vividity and power to move any cinemagoer is the execution in Army of Shadows, whereby three of its main players in the French Resistance of WWII kill a young man who has betrayed them. Melville makes use of ambient noise to give the setting context, referencing the sound of a gun in dialogue to highlight the need for stealth. The silence creeps further and further in as the boy is strangled, finally rushing away in an awe-inspiring wave of music as the room is left empty save the leader reflecting on what has just transpired- paired perfectly with Melville’s rigorous direction.

The man peppers things from as large as trains to as tiny as footsteps into his scenes to quickly sharpen the sense of suspense that permeates his work- silence always implicitly stating a looming shadow of a conflict that hangs over each exchange, glance, movement: Anything can be elevated with a coiled spring of tense energy Melville can trigger at his leisure and hold onto to harass us, fear as one of the many weapons in his cinematic arsenal.

Control

Moreso even than the famed Stanley Kubrick, Jean-Pierre Melville is a director with beautifully refined control over the medium. His touch is light enough not to disturb the process of the movie and yet utterly meticulous in how it reaches every facet of the film-making process to ensure absolute cinematic effect- where Kubrick’s overpowering presence can throttle the mood of a movie.

A big part of this difference is patience. Melville is happy to take any situation, both intense and calm, with as much time as he requires. The Camera drifts and sits and shudder whenever he sees fit and there is never a moment which speaks to a rigidity in his visual language- always reflexive and ready for any situation. In this, his style is difficult to pin down and thus becomes more expansive and absorbing than more acutely focused minds of the medium.

Yet despite this, a mark of Melville is his specificity. His exactness in achieving his goals and the precision with which the camera moves, the actors are blocked and the sound seeps in. Developing a form vague enough to enthral an audience and still strong enough to hold them transfixed is down entirely to the details: Refusing to work with flashy editing techniques like fades in favour of simple, swift, authoritative cuts. Making use of simple camera moves that are limited by time and movement- in that when he holds the camera is static and when he makes use of complex controls, the shot does not last very long. In doing this, Melville hides the seams of cinema remarkably well and provides an entrancing experience married to the ambiguity of its writing, rather than hampered by a plot that refuses to reveal itself like overtly lucid, abstract works.

Confidence

There is nothing in cinema as crucial as confidence. You can feel when a movie is failing to achieve its potential and when the artists behind it are struggling with their ideas. No matter how strong his scripts are, Melville handles them with a confidence that every budding patron of cinema should study in detail. His mediocre Les Enfants Terribles and Leon Morin, Priest both feature the same fantastic singular sequences as his greatest work- making full use of the cinematic medium and finding scenes in these lesser scripts with which he can grab the audience and coast along the rest of the ride.

That in mind, as we covered in his control Melville never becomes complacent. He is able to cushion the weaknesses of his lesser pieces but that does not mean that mediocrity is enough to settle for. The man consistently makes it clear to his audience not only that he knows what he’s doing- but that he knows what he’s doing three steps ahead of where we are. A vital part of cinematic confidence is instilling in your audience an abundant desire to watch the rest of your work- promising great things to come through careful build-up and, as Melville does so impeccably, hinting this through concise manipulation of things like sound, pacing and visual design.

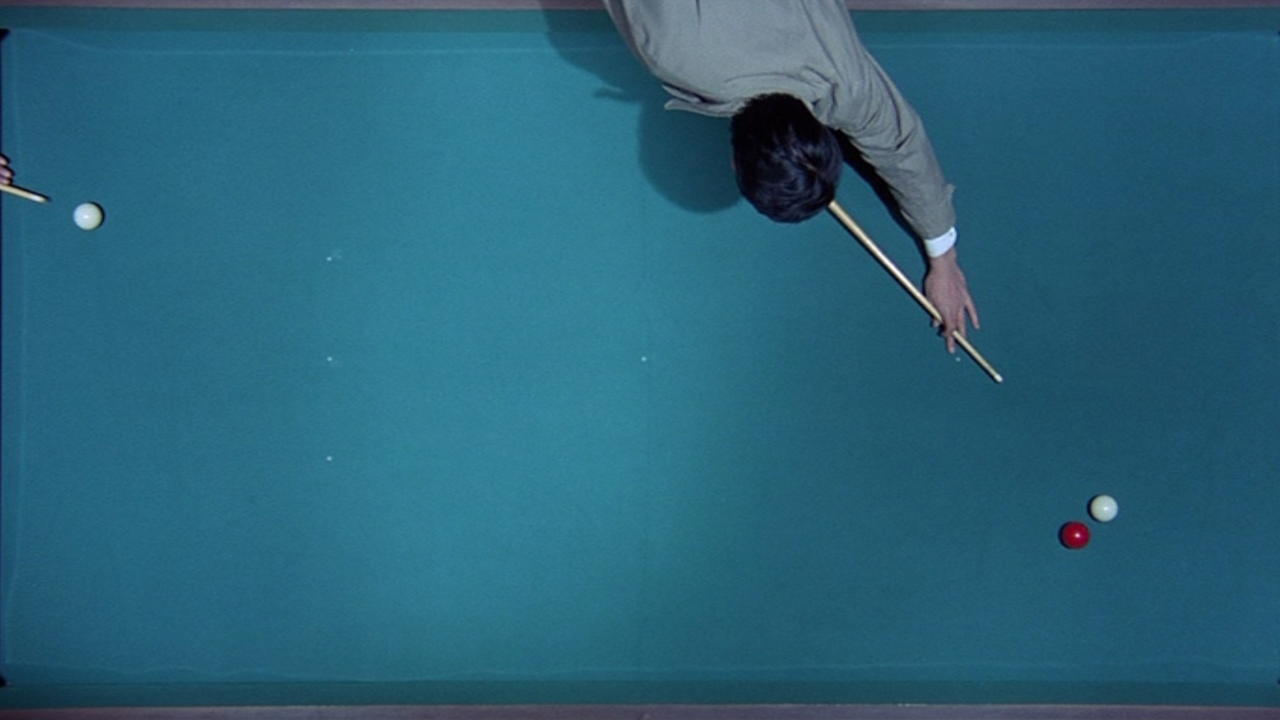

No-where is this confidence and its implications for the audience better realised than in the heist from Le Cercle Rouge. The scene in 25 minutes long- a large portion of the flick as a whole- and features absolutely zero dialogue. This is, however, not a hindrance for Melville; he does not write or direct the sequence with speech as an obstacle he has to work around- but a tool. The way he separates the heist from the rest of the movie by devoting such a great amount of time to it, as well as stripping away speech, demonstrates total faith in what he has to show us. Each second of the scene builds momentum for the next, promising a payoff that is richly rewarded in return for our undivided attention- just the same way that each scene of each movie he has made remains fascinating for every single frame.

You must be logged in to post a comment.