‘Dunkirk’ is unlike any other Nolan film you may have watched. It is perhaps his most experimental piece of filmmaking since ‘Memento’, and probably ‘Inception’. There are huge risks he takes with this one (to be discussed later); whether they pay off or not are certainly matters of personal choice, but it does illustrate command and an uncompromising stand on the man’s part.

One of the greater risks was the film’s historical setting. Nolan has, for the most part, worked on original scripts beaming with new ideas. ‘Dunkirk’ would be his foray into completely new territory: a film based on an actual historical event. While I had no doubts in Nolan’s ability in handling the subject, I was overcome in the way the director succeeded in lending the film his inherent touch with the kind of subject matter it had, giving us a very different kind of war film.

‘Dunkirk’ is based on the incredible true story of the evacuation of close to 300,000 stranded men, belonging to the allied British, French and Belgian forces, upon being surrounded by the German forces. Following the battle of France, the allied forces were forced to retreat to the northern French coast by the German resistance. The stranded soldiers were then rescued from the beaches and harbours of a small French town, after which the movie is named.

Following the decision of the commander of the British Expeditionary Forces (BEF), pertaining to evacuate personnel from Dunkirk via the English Channel, the German High Command issued a halt order, charging the Luftwaffe, its military air force division to prevent the evacuation at all costs. The Luftwaffe, though facing resistance from the British Royal Air Force (RAF), thus frequently bombed and gunned down hoards of trapped soldiers, and sunk and destroyed numerous rescue ships, making them fish in a barrel, awaiting their fate.

With the evacuation underway, a rescue fleet was assembled including destroyer ships from the Royal Navy, and hundreds of fishing boats, merchant boats, and leisure yachts, some of them voluntarily provided by civilians in an attempt to bring the helpless soldiers home. While the rescue operation off the coast of Dunkirk started slow, the British were able to rescue over 300,000 men within eight days, enlisting the services of close to 800 marine vehicles. As with any war, the losses too were huge. Nearly 70,000 BEF soldiers lost their lives, and all weaponry, tanks, and equipment had to be abandoned prior to the evacuation. The then British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill called it a “miracle of deliverance”, while at the same time accepting that it wasn’t a victory either. “Wars are not won by evacuations”, as he said.

For a more detailed insight into the history behind the film, this article may be a good read. For now, without further ado, we’ll get to explaining the plot and its ending.

Plot Summary

Like many of Nolan’s other works, this film too follows a non-linear approach to storytelling, which is pretty non-conventional for a film of this nature. Apart from its non-linear screenplay, Nolan also chooses to tell the historical tale as a Triptych, that is, involving three different perspectives that somehow find interrelation or congruence towards the end. Three separate POVs provide the viewer with an insight of what went into the evacuation; how ultimately it was a victory for all the people who worked together to make the ‘Miracle of Dunkirk’ happen.

The three different perspectives are related to the ground, naval, and aerial modes of combat, and are literally spelt out for the audience in the first fifteen minutes of the film or so, as The Mole, The Sea and The Air. What’s more, these sequences, in the film’s timeline, last for differing amounts of time, or as Nolan himself said it, exist in “different temporalities”. According to the maverick director, the soldiers stayed stranded on the beach for almost a week, the events at sea lasted a whole day, and the aerial warfare lasted nearly an hour, because that’s the amount of fuel British Spitfire planes would be carrying. The three different sequences play out separately in the beginning, with the scenes continuously oscillating back and forth, only to bring them all together in a crescendo of well mounted pieces, backed by Hans Zimmer’s winning score, in a very, well, Nolan-esque finale, for the lack of a better word. Now, we offer up a breakup of the plot, under the three different perspectives, arranged in a linear fashion.

1. The Mole

The film opens with a group of soldiers scourging the streets of Dunkirk, when they are fired upon by German soldiers. All except Tommy (played by Fionn Whitehead), a British army private, are gunned down one by one. A startled Tommy tries to escape and makes his way to the Beach of Dunkirk, where he sees soldiers lined up for evacuation, and crammed up on the mole, from where they are to be loaded to the next ship leaving the shore.

While there, he befriends Gibson (Aneurin Barnard), who appears to be burying his comrade. The two men then carry a critically injured soldier on a stretcher, rushing and dodging, as they hope to make it to a departing ship, in a stunningly shot sequence. Upon being denied entry to the ship, they hide under the mole, in hopes of sneaking aboard the next ship. However, the ship is attacked and sinks eventually, but the duo end up saving another private, Alex (Harry Styles) from the wreckage due. The three are able to board another ship sometime later, where they are offered food, warmth and a little comfort. This too doesn’t last and the ship is hit by a torpedo, presumably from a submarine (referred to as a U-Boat in the movie), and sinks, leaving the men struggling to make their way to the shore. While swimming back, they attempt to get on a row boat but are refused owing to less space, by Cillian Murphy’s character, who plays another unnamed soldier, and has a greater part in ‘The Sea’ sequence.

Just in case you were wondering, “mole” here doesn’t refer to, well, its common interpretation of a spy. It would have made some sense, you will know as you read on, but it is actually far from it. Mole here refers to an architectural element; it is the large pier like structure on which the soldiers were crammed up, almost like sheep, awaiting to board the next ship. Its significance in the story of Dunkirk, is much more than providing a claustrophobic setting, which also by the way, it does effectively. Since the actual harbour was destroyed by German bombing, and the beaches were too shallow for large ships, the marine vessels were lined up along the eastern mole. The idea of using the mole for getting soldiers off, and the subsequent evacuation was overseen by Captain William G. Tennant. This eased the evacuation process, since the mole also functions as a breakwater, providing sufficient depth to make way for large vessels, and just enough space for soldiers to board.

The next day, Alex, Tommy and Gibson tag along a group of Highlanders (Scottish soldiers) while they seek refuge in an abandoned boat far from the waters, in the hopes that it will be afloat once the high tide hits in a few hours. Since the boat is beyond the marked British perimeter, Germans start shooting at it by way of target practise. Once the tide hits, the boat starts buoying, but the group soon realises it won’t float because of the bullet holes. The group then decides to take some weight off the boat, leading Alex to accuse Gibson of being a German Spy, because of him being suspiciously mute during their ordeal. Tommy defends him, but Gibson reveals himself to be a French soldier, and that he had assumed a false identity, the one of the British soldier he buried, to improve his chances of evacuation from the coast. The boat finally sinks, and among the ensuing peril, Gibson loses his life.

Tommy and Alex, while now being stranded at sea, try to get aboard a minesweeper (A naval warship for minesweeping from the sea), but that too is sunk by a German aerial bomber. The duo is then FINALLY rescued by Mr. Dawson’s civilian yacht that arrives on scene (from the sea sequence, to be discussed in the next section), allowing them to return to England after they board a train from Dorset. Back home, they are being hailed as heroes, even though it was a military defeat, and Alex doesn’t feel like one. “All we did was survive!” he says, following which Tommy reads Churchill’s now iconic speech, that he finds published in the newspaper, reasserting that they may have lost the war until that point in time, but saving 300,000 lives that would have otherwise been obliterated (or captured), was in itself a tremendous moral victory in times when war and loss were omnipresent.

2. The Sea

The second sequence begins in parallel with the first sequence, roughly ten minutes into the film, occurring at presumably the last day of the week long timeline of ‘The Mole’. The Royal Navy enlists civilian vessels and private boats to accompany in the evacuation ensuing at Dunkirk. Mr. Dawson, played on screen by Mark Rylance, owns a leisure yacht named ‘Moonstone’, but insists that he take it out himself, accompanied by his young son Peter (Tom Glynn-Carney) and hastily joined by Peter’s friend, George (Barry Keoghan) who wishes to do something of notice in the war. As they are sailing, they encounter the sole survivor of a sunken minesweeper that presumably left Dunkirk the previous night (as shown in ‘The Mole’), and the unnamed soldier played by Cillian Murphy is rescued and brought on board. Murphy’s character is shell shocked (PTSD) from the ordeal, and upon learning that they are travelling back to Dunkirk and not England, he tries to resist, and in the process, ends up pushing George down the stairs of the lower deck. George suffers an injury to the head, later revealing that he was unable to see, eventually succumbing to them and meeting an untimely end.

The group then encounters a crashed Spitfire plane in the midst, and Dawson steers to attempt saving the pilot, eventhough he is uncertain, rescuing RAF pilot Collins (Jack Lowden), one of the three engaged in direct aerial combat with the Luftwaffe in the ‘Air’ sequence. In the ensuing conversations, it is also revealed that Mr. Dawson had an elder son, who was a pilot, who he lost in the beginning of the war.

Proceeding forward, and avoiding fire from the ongoing air battle, Dawson and crew come across another minesweeper (the same one that Tommy and Alex are trying to swim to; it is here when the convergence of the three perspectives begins) taking fire from the German bomber, getting hit and spilling oil onto the sea escalating the already difficult ordeal. The German bomber plane is taken down and crashes into the sea, but the wreckage ignites the oil, burning several soldiers. Dawson and Peter rescue as many soldiers as they can, including Alex and Tommy, and drop them off at Dorset. Dawson emerges an unlikely hero, and upon being asked about George, Peter lies to Murphy, telling him that George will be alright, sparing the shell shocked soldier the guilt of having been responsible for a boy’s death. Back home, Peter honours George’s wish by submitting his photograph to the local newspaper, which later lauds him as a local hero.

In a way, I couldn’t help but feel George’s story was somewhat a replication of the Dunkirk incident on a miniscule scale. What is to be noted in both cases is, that the story that is told is more powerful than reality. Because sometimes, people deserve more than the truth, sometimes, people deserve to have their faith rewarded.

3. The Air

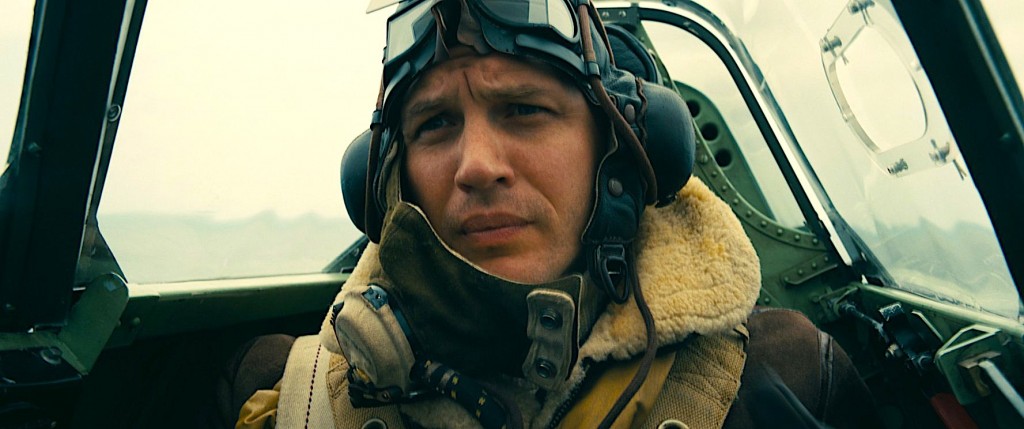

The sequence begins with a trio of British Spitfires being dispatched to provide air support to the trapped forces at Dunkirk, piloted by Farrier (Tom Hardy), Collins and an unnamed Squadron leader. While flying over the English Channel, they are attacked by a Luftwaffe plane and lose their squadron leader, also damaging Farrier’s fuel gauge. Having been informed earlier, that they had to keep flying at a low altitude to preserve fuel, as they only had an hour worth of it before they had to return, Farrier continuously corresponds with Collins about his fuel level and intuitively leads the duo onwards to France. They encounter another German bomber that Farrier takes down, but not before Collins’ plane gets hit and he is forced to crash land in the middle of the sea (later rescued by Mr. Dawson).

Farrier reaches Dunkirk alone and engages with the German bomber threatening evacuation attempts (the same one that crashed igniting the spilled oil), taking him down valiantly. The soldiers clap and cheer as Farrier flies above them on reserve fuel. The rotor soon stops spinning implying that the plane is totally out of fuel, leading Farrier to land the plane on the beach, albeit far from the British perimeter. Accepting his fate, he climbs out of his plane, sets fire to it and watches in the distance, as German troops surround him and take him in as a prisoner of war.

Themes and Interpretations

While it concerns itself with the cinematic retelling of a historic event, Nolan’s ‘Dunkirk’ is hardly a war film. It works more on the lines of a survivor flick, or as Nolan himself put it, a “suspense film”. There are battle sequences, but they are only montages to show the great odds against which the soldiers had to survive. Perhaps for this reason, Nolan consciously decided against giving his characters any backstory whatsoever, and minimal dialogues, casting relatively newer faces for the ‘The Mole’ sequence, which is also incidentally the longest of the three. Nolan’s film is then unsurprisingly void of a lot of drama that usually entails a movie from this genre, but that is in no way saying that the film doesn’t have any emotional moments.

The whole film works this way, there is no introduction to the characters and no closure about their fate; no precursor as to what led to this war and evacuation, and no premonition of what followed it. The film doesn’t look to inspiring speeches, or political camaraderie, concerning itself with one and only one thing: Survival. The film is merely an account, much like a slice of life film, that has just been lifted from a particular section of history and retold as a simple tale of human resilience, the will to fight in the face of all odds, the will to find what one calls, “Home”.

Another questionable but conscious decision that Nolan took with the film was not showing the antagonist on screen. The film, not only lacks the presence of flaring German General shouting orders, it also doesn’t show one German soldier behind arms well until the final scene. This ended up working big time for me, because in a way, this establishes that the faceless enemy is omnipresent. Since the audience knows zilch about the proceedings on the German side, and the film doesn’t show any strategic discussions or base meetings on their side, you don’t know when or how the Germans strike. It lends a handful to the uncertainty factor, an element which is played around with a lot of times in the film.

Time is another omniscient theme in Dunkirk’s narrative, or rather the lack of it. Everything that they decided to do was measured, and had an impact on the interconnected stories. One of the major things that plays out in Dunkirk’s favour is that it doesn’t give you time to settle, it’s pacing is breakneck to say the least, while other Nolan movies unfurl somewhat leisurely, hence the short running time. For this reason alone, I think, it may be one of the frontrunners at the academy this year in the editing department. It operates with the urgency of a ticking time bomb, which is also reflected for the most part in Zimmer’s score. Interestingly, the constant ticking you hear in the background score is actually Nolan’s pocket watch that Zimmer recorded for the film’s score.

Final Word:

In closing, I am sure that Dunkirk will remain a highly talked about feature in the times to come, such is the nature of the film. While some of the decisions Nolan took for the way the film came out to be might put off some viewers, we know at the end of the day, it’s about how the film made YOU feel. Whether those decisions worked for you or not completely ends up being personal opinion. For me, they did. For anyone else seeking to understand the film, the themes are spelled out in the final trailer for the film, and etched in my mind ever since it first aired. “Hope is a weapon. Survival is victory.”

Read More: Inception Ending, Explained

You must be logged in to post a comment.