“The times were a changing”, crooned folk singer Bob Dylan, perhaps not knowing just how true his words were at that time. All forms of art were changing radically in the 1960s, as society heaved and grunted and brought about a counter-culture revolution, the likes of which the world had not ever seen before.

The Cold War, the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, and Senator Robert Kennedy headed for the presidency, brought about a profound sense of mistrust between the youth and the establishment. Young people lashed back at authority, vowing to trust no one over thirty, protesting the war in Vietnam, which had become a hugely unpopular war that America was losing. The Americans very nearly went to war with Russia and Cuba, as Kennedy stared down Russia during the Cuban Missile Crisis, perhaps showing his mettle as a President before his death. Live television allowed audiences to see Kennedy’s killer himself assassinated on TV the following day, while images broadcast home from Vietnam showed the futility of that dirty little war. Man raced to the moon, with the Americans landing in 1969, just a few years after Kennedy declared that man would land on the moon by the end of the decade. Rioting in Detroit and the South reached manic heights as blacks and whites clashed in the Civil Rights Crisis, leading to marches on Washington and the eventual signing of the bill by Johnson that gave blacks equal rights in all areas. At the end of the decade, thousands gathered in peaceful protest to watch rock bands perform at Woodstock, which would come to define the 1960s.

The extreme revolution in society saw art change because art reflects society. Yet cinema was the last major art form to change, though when it did, it did so virtually overnight. Television, literature, music, theater, and paintings all changed long before the film did, and everyone wondered what the hold-up was, but of course, it was the old guard struggling to hang on to their dwindling power. As the old directors retired or died off, Hollywood had no choice but to take chances with the new filmmakers emerging, and their work was bold, innovative, and heavily influenced by that of the fine directors at work in Europe.

It would lead to a remarkable time in film, headed directly into the seventies, the most exceptional ten year period in movie history. Interesting, though they worked in American film, three of the directors on this list are British, as they chose to make films in America. Two of them would win Academy Awards for Best Director, the third would revolutionize the horror genre in ways no one ever saw coming.

The leader of the French New Wave, Jean-Luc Godard, once said he could make a film with a guy and a girl and a gun, and he was right. The film that changed everything in American cinema did just that, and never looked back.

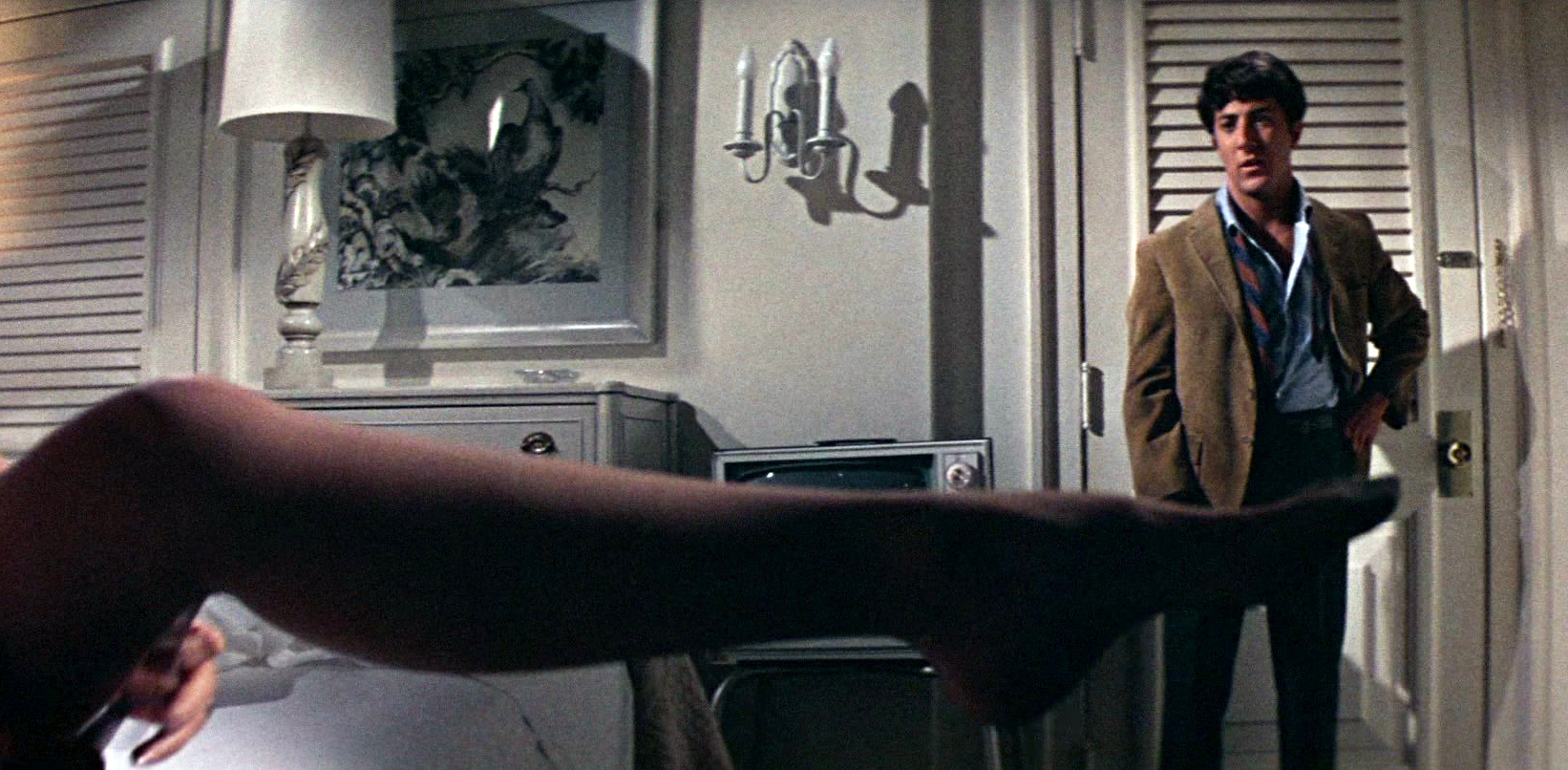

10. Mike Nichols – The Graduate (1967)

Newly educated, a college graduate with no other life experience save the classroom, Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) returns home the conquering hero but is quickly aimless, unmotivated, and not interested in anything. He spends his days in his parents’ pool, drinking beer, and his nights in a hotel in the arms of Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), his mother’s best friend. Their relationship is pure sex, nothing more and becomes dangerously complicated when Ben falls in love with her daughter, Elaine. The love Elaine has for him is shattered when the mother exposes her relationship with Ben to her. But Ben is relentless, he is in love, Elaine completes him and he knows it. She is the only person he has ever wanted to be with. The film spoke to the disenchanted youth of the time, to the sadness the young possessed at not being able to trust their elders. Ben simply cannot believe the cruelty of Mrs. Robinson, nor understand why she does not think him good enough for her daughter. The film is punctuated by a haunting song score by Simon and Garfunkel, but the actors carry the day and wisely Nichols allows it to happen. With that haunting ending shot, both Ben and Elaine uncertain of their future, Nichols crafts the defining cult movie of the 1960s

9. Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins – West Side Story (1961)

Though they fought constantly and eventually were not speaking, I wonder if they realized while making the film they were changing the course of musical film history. A smash hit on Broadway, the transfer to the screen would be a formidable job, so they took to the streets of New York for their Romeo and Juliet tale set in the world of gangs. Wise handled the dramatic sequences while Robbins took care of the dance sequences, turning the fights between the gangs into breathtaking ballet, jazz and modern dance numbers. The film had a furious energy from the opening sequence through to the end, it never seemed to stop moving, everyone, everything was always in motion. The cast was virtually unknown, except for Natalie Wood as Maria, but two of them won Oscars, George Chakaris and Rita Moreno, for their supporting roles. Dance became more than ever, a formidable language as never before, performed with anger and rage. The film won Oscars for both men. Wise would win again for ‘The Sound of Music’ (1965).

8. Alfred Hitchcock – Psycho (1960)

Hitchcock learned so much working in TV: how to shoot fast and cheaply, and how to surprise his audience in ways no one had ever thought of doing before. Based on the strange case of Ed Gein, a serial killer who was also a cannibal, Hitchcock fashioned this story. Shot in black and white in twenty-eight days for less than a million dollars, he altered the face of horror cinema by making his killer the boy next door; nothing supernatural here. His star is slaughtered just thirty minutes into the film, a vicious killing in the shower by a knife in which the audience thinks they see a lot more than they do. From there, it veers off into madness as the killer is not at all what we expect him to be and is utterly mad. Hitchcock took many risks that paid off with the film, from killing off Janet Leigh, which threw the audience off track, to casting boyish Anthony Perkins as the insane killer, to insisting critics not to reveal major plot points and finally, not allowing anyone to be seated after the film had started rolling. I am not a fan of Hitchcock, but he got everything right here and created a much more realistic and terrifying horror film. Supernatural creatures like vampires, werewolves, or mummies did not scare audiences anymore, but a knife-wielding maniac chilled them to the bone.

7. Sydney Pollack – They Shoot Horses Don’t They? (1969)

One of the most nominated films in Academy history without the benefit of a Best Picture nomination, this powerful study of the thirties was nominated for nine Oscars, including Best Actress (Jane Fonda), Best Supporting Actor (Gig Young), which it won, Best Supporting Actress (Susannah York) and for Pollack as Best Director. Seeing the dance marathon as a metaphor for life, he plunges into the fast-moving world of crooked contests. Thinking they are dancing for a five to ten thousand dollar prize, the contestants have no clue every meal is deducted, every glass of water, their cots and blankets cost them, they might walk away with a few hundred dollars for punishing themselves for more than a month. Jane Fonda is searing as Gloria, the caustic and bitter young starlet rejected by Hollywood, adrift and alone, dancing to get away. Gig Young is creepy, as is the all-knowing, crooked MC who spends days and nights shouting, “Yowza! Yowza!” Into the microphone. Red Buttons is heartbreaking as the tough old Sailor, York brilliant as the damaged stage actor, and Michael Sarrazin is excellent as the sad-eyed partner for Fonda, who will do her a service at the end that the title speaks of. Directed with power and careful intimacy for the actors, it marked the first time Pollack was recognized as great, but certainly not the last.

6. Stanley Kubrick – Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Imagine a few years after 9/11, an up-and-coming director decides to make a nasty comedy about it, a vicious black comedy. In the immediate years after Kennedy stared down at Russia during the infamous Cuban Missile Crisis, Kubrick gave us Dr. Strangelove… (1964), a stunning black comedy about the end of the world coming about by accident, by human error, and as it is unfolding, governments try to minimize the impending destruction. Courage? Guts? You bet it was. A renegade Colonel takes a bomber and heads to Russia armed with a nuclear bomb, causing the US to go into panic mode, calling Russia to let them know they are not under attack, but a nuclear holocaust is coming their way. Is there any chance Russia could see themselves clear and not counterattack with nuclear missiles aimed at the States? Well, of course not. Darkly comic but deeply disturbing, the picture contains stand-out performances from Sterling Hayden, George C. Scott, and, in several roles, the extraordinary Peter Sellers. Remarkable on so many levels and black right through to the end, Kubrick had the great sense not to waver from his vision. It became a habit.

5. Robert Rosen – The Hustler (1961)

Cities all have them pool halls, sometimes in the back of other businesses such as a smoke shop or magazine store. Some were stand-alone establishments, but they all looked and smelled the same: clouds of smoke, with the smell of cigarettes, cigars, stale smoke, whisky, and sweat. The characters who hung out were dubious-looking folks, tough guys, no question, the sort of people you did not mess with. And man, could they shoot pool. Robert Rosen captured that world to perfection in his remarkable film ‘The Hustler’ (1961), an uncompromising film about a selfish, unspeakably arrogant young pool player on the rise who learns harsh life lessons when he mistreats the woman who loves him. Paul Newman is brilliant as Eddie Felton, Piper Laurie superb as the doomed woman who loves him, Jackie Gleason sublimely confident as Minnesota Fats, and best of all, George C. Scott as the demonic Bert, who manages Eddie and ruins his relationship. Dark, gloomy, often without any sense of humanity, the film is a tough go, but Newman draws us in. Rosen was among the first to see that Newman was at his best as a bastard. It takes great courage for a director to cast a major star and then make him a cruel, unfeeling man. Rosen captured this world beautifully and those who inhabit it to perfection.

4. Arthur Penn – Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

Hired by producer Warren Beatty to direct the film, Penn had worked with the actor on ‘Mickey One’ (1964) and Beatty believed Penn had the smarts and vision to share the film with him. The film was strongly influenced by the French New Wave cinema emerging from France, but Penn conceived many exciting aspects in creating the picture. Number one was making the tragic criminals metaphorically modern young outlaws, not unlike the kids in America who were lashing out at the authority governing them. Beatty and Faye Dunaway were iconic as the bank robbers who graduated to murder, with great support from Gene Hackman, Michael J. Pollard and Estelle Parsons in the fast-paced rollicking film. There were moments of grand fun, suddenly brought to a halt by murder or the realization that they were eventually doomed, and every step they take is one towards their eventual doom. The infamous death scene is now one of the movie’s most famous massacres, a shocking, swift death for the two outlaws, when they least expect it. Penn directed the picture with energy, giving it a jaunty feel, which he would suddenly crush with an intense sequence. This film was the changing point in American film, the one that forever altered everything about movies and opened the door for the New American Cinema movement. Penn did fine work after, but nothing like this. Nominated for ten Academy Awards, the film won just two.

3. John Schlesinger – Midnight Cowboy (1969)

Hiring a British director to make this very New York film was a stroke of genius because he did not get caught up on what New York was known for. He took his cameras to the street, to capture the street life, to find the living heart of the city, to explore its pulse and what made it tick. Shooting often without permits, he superbly guided his game actors to some of the best work of their careers. Dustin Hoffman is the tubercular pickpocket Joe Buck (Jon Voight) meets and foolishly trusts before realizing he has been taken. However they develop a curious bond and come to need each other to stay alive. Ratso (Hoffman) dreams of Florida where the sun and orange juice will burn the disease out of him. In many ways, it is a modern day Of Mice and Men tale, set in the harsh streets of New York where it is survival of the fittest. Joe comes to New York, straight out of Texas hoping to become a male stud, but finds he does not have the street smarts or the contacts and ends up servicing young gay men on 42nd street. Eventually heartbreaking, the film is a powerful love story about two men who find they need one another but lack the smarts to survive. Schlesinger brilliantly captured the energy of the city, and the two men moving about it, trying to stay alive as everyone is talking at them, and they do not hear a word they are saying. Truly shattering.

2. Stanley Kubrick – 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

One of the most brilliant films ever made, but also amongst the most confounding in that Kubrick challenges his audience to make of the film what they will, allowing them to decide what it is about. What is the monolith, what does it mean, what happens when it appears. The film advanced the language of the cinema as much of it is silent, or without dialogue. Beginning at the Dawn of Man, we encounter prehistoric man, still apes really, and to them the monolith appears. One of them touches it and there appears to be an advancement in intellect as they figure out how to hit with a bone, how to kill with a bone, thereby bringing their tribe food and control of the water hole. From there we advance millions of years to where mankind has found the monolith now on the moon, again they touch it and they find themselves headed to Jupiter. On the way the computer breaks down and kills one of the men, and tries to do away with the rest before it is disconnected in a chilling sequence. We end up on Jupiter where mankind will connect with the aliens there to create the star child, staring ominously at the audience as it heads, we expect, to earth. The film, for me, is about the advancement of intellect, raw brain power. Technology fails miserably when they must disconnect the super machine meant to drive the ship. Using the music of the classical masters, the great star-ships move through space performing a virtual ballet of movement; it is remarkable. Critics initially hated the film, but it was a huge success on college campuses, bringing critics back to the picture where they changed their tune and declared it a masterpiece. It was the first realization that Kubrick was beyond good, he was a genius.

1. David Lean – Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Though a biographical film, it is also a grand adventure, and a penetrating character study of an extraordinary, deeply flawed man who altered the course of the First World War with what he accomplished in the deserts of Arabia. T. E. Lawrence was a British officer, an oddball that no one knew what to do with, so in essence they banished him to Arabia hoping he would settle in and disappear. Instead he banded the warring tribes of Arabia together to create a fearsome fighting force, and went to work conquering the enemies of the Arabians and the British. With startling desert vistas, the director plunges into oceans of san, and heat which Lawrence came to love as his lifeblood. He conquers Aqaba from behind, crossing the desert to do so, knowing that their massive guns are pointed at the sea expecting a naval invasion, goes guerrilla in the desert and attacks who gets in his way. His flaws were that he was a homosexual when one was not permitted to be such, he loved bloodshed, loved to kill and enjoyed pain. It was said the only reason he escaped death at the hands of the Turks was because he loved being sodomized by their cruel Bey. Director David Lean brilliantly captures the life of Lawrence, not shying away from what he was, and gives us vast expanses of desert, with the gleaming whiteness of Lawrence’s robes turning crimson with blood to show his intense blood-lust. It might be a perfect film. Peter O’Toole is brilliant as Lawrence, with strong support from Anthony Quinn, Omar Sharif and Alec Guinness, superb as Faisal. And that Maurice Jarre score sounding as mysterious as the desert itself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.