The ten-year period that was the 1970s remains the most astonishing in film history because of the sheer quality of the work coming out of America. It would come to be known as the “director’s era”, a point in history when directors became all-powerful, making the films they wanted to make, often with subjects that had been previously taboo, eventually with outlandish budgets that would be part of what would bring this era crashing down.

New directors emerged out of film schools, bursting with knowledge of film history, enthralled by watching movies, and now they were to make them. Many emerged from television, having learned their craft in the fast-paced world of making a new show every couple of days. They would take Hollywood by storm and dominate the decade but become obscenely wealthy and spoiled; the budgets of their films would skyrocket out of control until one of them was responsible for bankrupting one of the oldest studios in the business.

Freed from the constraints of what was acceptable fare on movie screens, with language now an “anything goes” sort of thing, nudity and sexuality very frank, directors could explore what for years had been taboo. Holding their cameras up to society, capturing life, they created art. And what art! Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, William Friedkin, Peter Bogdonavich, Stanley Kubrick, Robert Altman, Sidney Lumet, Woody Allen, Brian De Palma, Sydney Pollack, Bob Fosse, Hal Ashby, Robert Benton, Alan J. Pakula, and Michael Cimino led the charge among American directors while foreign born Miloš Forman and Roman Polanski enjoyed great success in America cinema.

No director in the history of film would dominate a decade as Coppola did the 1970s. He directed four films, three of them top this list, the fourth just missed; he produced ‘American Grafitti’ (1973), which not only launched the career of George Lucas, but created a renaissance in 1970s music, clothing and spawned two hugely successful TV sitcoms. He created his own studio, wanting to help young directors make their films free of the tyranny of the studios, and was the first director to announce he was tackling Vietnam as a subject for his next film. Coppola was awarded two Best Director Awards from the DGA, along with two other nominations, and he personally won five Academy Awards for his work, Best Director for ‘The Godfather Part II’ (1974), along with two other nominations. Each film he directed was a Best Picture nominee, and he seemed to have an innate understanding of the coming video and digital media age.

He was a God in the 1970s. And he helped others on the way up, bringing attention to their work. Steven Spielberg, Martin Scorsese and George Lucas would have staggering impacts on the 70s, Spielberg most of all, as he and Lucas more or less created the blockbuster. They loved movies, old movies, each other’s movies, they just lived for cinema. They were the movie brats, a generation of gifted artists the likes we had seen before nor likely will again. What is astonishing is that so many of them are still active, still vital, making movies that impact the world. They are now the old guard, but looking at them together, presenting Scorsese finally with his Oscar, we could almost see the ghosts of their younger selves behind them, full of hope and promise.

They were once a group of up-and-coming artists who spent Sundays on the beach in a cottage rented by Margot Kidder, who fed them while they talked film. Coppola would hold court, listening to the ideas and enthusiasm of the younger men, George Lucas, close by. Across the room, dressed in a white three-piece suit, full of old-world charm, would be tiny Martin Scorsese, animated and talking with a machine gun delivery. Brian De Palma would be off seducing the newest girl to the group or watching John Milius surf. Sitting in the corner, quietly taking it all in was Steven Spielberg, the least sophisticated but the most gifted of the group.

I wonder then if they knew they were on the cusp of history, about to make their own history? About the list. Yes, Coppola holds the first three spots, and it killed me to leave Woody Allen and Sidney Lumet off. Neither will you find Michael Cimino for ‘The Deer Hunter’ (1978), and that was intentional in every way.

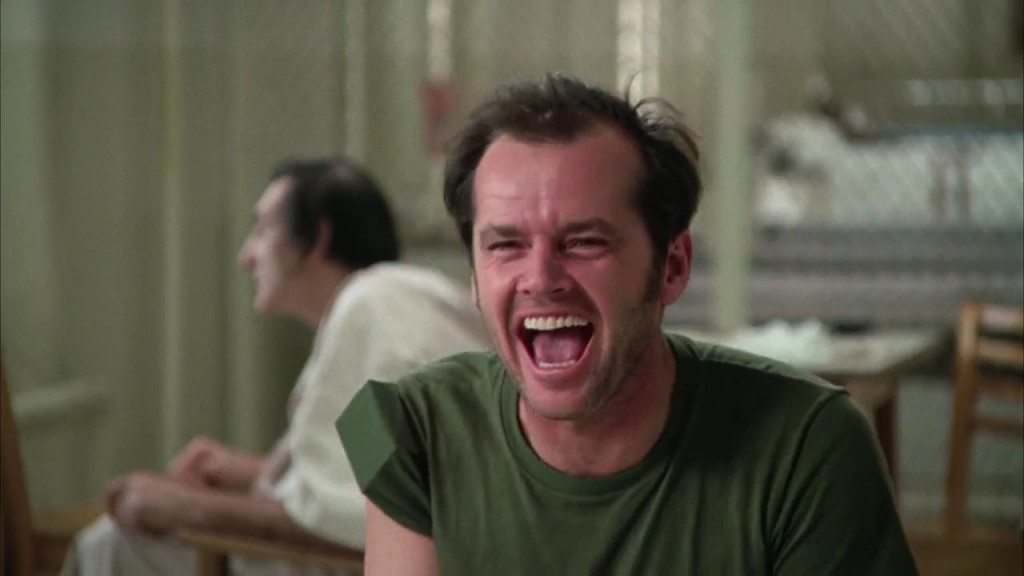

10. Milos Forman – One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

Knowing that no American director could bring the documentary-like, European feel he knew the film required, producer Michael Douglas sought out Czech filmmaker Forman who he believed had it in him to make the film. Douglas knew the director was the difference between a masterpiece and a dud. They found a mental hospital that permitted them to shoot using real patients as background characters. The doctor played the head of the place, and for eight weeks, they were in that place creating art. Jack Nicholson got the role of a lifetime as McMurphy, the rebel sent from jail to the hospital because he believes it is a cushier sentence, not realizing that he has been committed and they will decide when leaves. The war he starts with Nurse Ratched will bring about his doom, as she has metaphorically castrated each man, stripping them of their self-esteem. That McMurphy will not play her game is what will end him. What she does not count on is that the spirit of McMurphy lives on in each man, a small part of that rebel allows each man in their own way to be free and whole again.

Nicholson is as astonishing and breathtaking as McMurphy, portraying the role with such authenticity that we are never not looking at him. Louise Fletcher took the role no major actress wanted, Nurse Ratched, and chose not to play her as a monster, though her actions are monstrous, and make her one. The film swept the Academy Awards, winning the big five and remains one of the greatest American films ever made.

9. Bob Fosse for Cabaret (1972)

The most remarkable and powerful musical ever made, ‘Cabaret’ won eight Academy Awards, including Best Director, but lost Best Film to ‘The Godfather’. No other film has won so much without winning that top prize. Fosse directed the film with precisely what was needed, sleaze and sex, without once trivializing the very serious subject matter, that being the steady rise of the Nazis in Berlin as Hitler made his move to power. In an Oscar-winning, sensational, star-making performance, Liza Minnelli became a star as Sally Bowles, the manipulative singer who sleeps around looking for someone to take care of her. As the MC of the nightclub, Joel Grey is an allegory of evil, sleaze, Nazism, corruption, decadence, and even Hitler, and he is brilliant in his Oscar-winning work. Fosse allows only two songs to take place out of the club; all others happen on the stage, commenting on the times.

The film moves constantly, the choreography is superb, the portrayal of the rise of the Nazis haunting. Is there a more chilling moment in any musical than the scene in the beer garden? A beautiful, blonde, blue-eyed boy stands and begins to sing a song, his clear voice reaching all ears. As he sings he becomes more frantic, people join in and we realize he is a Hitler youth, and the song Tomorrow Belongs to Me, a Nazi anthem. The most searing musical ever made.

8. Steven Spielberg – Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977)

Fresh off the success of ‘Jaws’ (1975), the wonder-kid was wooed by each of the major studios to make his next film. He decided to make a film about mankind’s contact with alien beings for the first time, though that turns out not to be quite accurate. The film is a burst of light from its beginning in the race to encounter the aliens at their selected point. What is interesting is that as the government and the United Nations unlock the codes being sent to them, hundreds of ordinary men, women and children have had burned into their minds an image that they cannot shake for those that figure it out, they find themselves at Devil’s Tower in Wyoming where the encounter will take place.

The final forty-five minutes of the film are breathtaking, like seeing a God. Mankind does encounter benign, gentle aliens, making contact in a stunning, peaceful sequence filled with love. Richard Dreyfuss is superb as the every-man who has a close encounter that becomes an obsession that will become part of the most remarkable event in the history of mankind. Spielberg fills the screen with awe, with majesty, with a wonder we had not experienced before. When the small alien, eyes wise beyond our comprehension, approaches the French scientist, and they communicate with sign language and a smile, you will weep. But you will be weeping for joy.

7. Alan J. Pakula – All the President’s Men (1976)

Based on the Pulitzer Prize winning novel by reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein of the Washington Post that would lead a recently elected President to resign, director Pakula made the perfect decision to make the film as a detective style thriller, a neo-noir. Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman portray the two reporters who stumble onto the story of the century, and the further they dig, they realize how far-reaching it all is. Jason Robards won an Oscar and all the critics awards for his gruff but mentoring Ben Bradlee, and both leads are excellent. Hal Holbrook is quietly superb as Deep Throat, the insider who fed them information and kept them on track.

From a simple break-in story, they put the pieces together at considerable peril to themselves and brought down a President who had recently won the election with the most one-sided victory in the history of America. The film’s designers did an astounding job of creating the offices of the Washington Post, and watching the film now, it is alarming not to see computers, but rather typewriters. Very much a film of the time, but so literate, so intelligent, it is timeless. Pakula won several critics awards for Best Director for his achievement and received the only Oscar nomination for Best Director of his career. The finest film about journalism ever made, a remarkable historical film

6. Steven Spielberg – Jaws (1975)

The genius of this film is how little we see the shark, the massive great white shark feasting on bathers off the East Coast. Though three mechanical sharks were built for the shoot, two of them sunk to the bottom of the sea, so Spielberg improvised on set, showing the attacks from the point of view of the shark. Using the adage, less is more, the director showed the impending attack, the devastation of the attack, and the aftermath. With a superb, simplistic score by John Williams that launched the career of the greatest film composer in history, the film is genuinely terrifying.

The performances of the actors are terrific, especially Robert Shaw as Quint, the tough old Ahab obsessed with getting this killer, though we sense, rightly, he is doomed. Roy Schieder and Richard Dreyfuss are equally good, though the director is the star of this film. Oddly, Spielberg was famously snubbed for a Best Director nomination, though the film won three of the four it was nominated for and revolutionized the horror film. Spielberg became a household name with this, and has remained such ever since.

5. Stanley Kubrick – A Clockwork Orange (1971)

The greatest thing you can say about this startling drama set in the future is that today, forty years later, it still feels futuristic, it still seems possible. The finest film of Kubrick’s career, based on the Anthony Burgess novel about a dystopian society in the near future, we encounter Alex (Malcolm MacDowell) in the opening frame, where his baleful stare pulls us into the film. The leader of the droogs, Alex spends his nights beating, pillaging and raping anyone in his path, all with a gleeful smile on his face. When caught and convicted of murder, he goes to prison where he is chosen to take part in a unique program that where any urge to do harm or wrong makes him physically ill. Cured, he is released, where he finds his life going full circle, all those he harmed coming back at him.

Kubrick directed the film superbly, giving McDowell a jaunty step, an upbeat demeanor throughout, even when conducting violence. He might be the most happy bad guy you will ever encounter. The fights are beautifully staged, almost balletic in their execution, yet shocking and frightening. The rape sequence is downright perverse as Alex bursts into song, crooning Singin’ in the Rain, as he kicks and punches. You want to look away but cannot. An always moving in your face, the camera gives the viewer a glimpse into Alex’s bizarre mind. It’s blackly comic and downright scary.

4. Martin Scorsese – Taxi Driver (1976)

One of the first things we see is steam roaring from a sewer grate, as though the metal lid were holding back Hell, which threatened to explode from below at any more mention. This is the New York City of the 1970s, when it was a dangerous city, where crime ran rampant, where Times Square was a haven for drugs, hookers and murderers. Travis (Robert de Niro) is a Vietnam veteran who cannot sleep so he takes a job driving a cab at night, going to the places in the city no one else will go. All around he sees filth, and wonders aloud when someone will come along and flush the entire city down the toilet, or clean it up. The more he thinks the further into despair he sinks. Meeting a twelve-year-old hooker, Iris (Jodie Foster) seems to push him over the edge and he decides it will be he who cleans it up. Damaged by the rejection of a woman he believes he is love in with, he buys an arsenal of weapons and gets himself into shape. When his assassination of a presidential candidate fails, he swoops in on the men and pimps who control Iris, slaughtering them all in cold blood. And the great irony, he is elevated to the status of a hero because he saved Iris, returning her to her home in Minnesota.

At the film’s conclusion we catch his eyes in the rear view mirror, and realize he is again a time bomb and will go off again. De Niro gives a seething performance of barely controlled rage and Jodie Foster is remarkable as the pre-teen hooker. Scorsese captures the hell that was New York before Giuliani, and never shies away from the tough aspects of the film. The violence is brutal and swift, the night always dangerous, the night-life dream-like. Superb.

3. Francis Ford Coppola – The Godfather (1972)

Upon being hired to direct and co-write ‘The Godfather’, Coppola poured over the novel and discovered the film, which to him, was a dark metaphor for the American Dream. Immigrants have come to America to seek a better life, wealth, and sometimes find it through crime. The Corleones have done that. Aging Vito (Brando) now in his seventies is the country’s most powerful Don, presiding over a criminal empire with fairness. He orders murder only when threatened, or when his family is threatened, but make no mistake, the old man is a killer. When an attempt is made on his life, idealistic war hero Michael (Al Pacino), his youngest son, is drawn into the family business and kills the men responsible. When the Don gets well, he grooms Michael to take over the business, which the other crime families see as a sign of weakness, though Michael proves more ruthless and deadly than his father.

Marlon Brando is superb as the Don, people often forget he was just forty five when he played this role, making it instantly iconic. Al Pacino carries the film as Michael, a remarkable arc, with strong support from James Caan, Robert Duvall, Richard Castellano, Diane Keaton, Abe Vigoda, Talia Shire, and John Cazale. Beautifully shot by Gordon Willis, the film is darkly lit, which plunges audiences into back rooms where the murder business takes place. The director brilliantly captures a family, one with a loving father, sons, daughters, wives, just like most of us, and yet, their business happens to be crime.

2. Francis Ford Coppola – Apocalypse Now (1979)

The lights went down, the screen was black. Slowly, a jungle setting comes onscreen, lush, green, beautiful. On the track we hear guitar music, then the whoosh of helicopter blades. As Jim Morrison mournfully croons The End, the jungle erupts into an inferno and just like that we are thrust into the war in Vietnam. Though ‘The Deer Hunter’ (1978) and ‘Coming Home’ (1978) might have beaten Coppola’s film into theaters, neither film matched either the artistry or power of ‘Apocalypse Now’ (1979), which captured the absolute madness but sensual quality of the war, a place where young men, soldiers could play God. Loosely based on Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Willard (Martin Sheen), an army assassin struggling with his own sanity, is sent on a mission to execute a decorated Colonel Kurtz (Brando) who the military believe has gone mad in the jungle and formed his own army. The further into the jungle and closer to Kurtz he gets, he comes to understand why Kurtz has acted as he has.

Robert Duvall as Kilgore steals the film, a high from where it never quite recovers, as a surfing obsessed nut who attacks a village to be able to surf. His infamous line “I love the smell of napalm in the morning”, is part of movie legend. The picture is in every way a stunning work of art, the cinematography the finest in film history, and the performances are impeccable. Told surrealistically, we feel the presence of Coppola, but never does he distract. As he boldly told critics at Cannes before showing them his film, “My film is not about Vietnam, it is Vietnam.”

1. Francis Ford Coppola – The Godfather Part II (1974)

Magnificent. Somehow Coppola surpasses the first film, giving this second an epic sweep, and becomes far more powerful than the first in exploring the reach and overwhelming power of the Mafia. Yet even with that scope, those stunning images of the immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, staring at Lady Liberty with such hope, such wonder, he brings greater intimacy to the story. Darker, richer, more complex than the first, somehow Coppola goes past his astounding work on the first film. Moving easily between the past and present, the film explores the past by showing how Vito arrived in this country, grew into a man, portrayed by Robert De Niro, and became a powerful crime lord, while the present explores Michael (Al Pacino), now at the height of his substantial power as the chieftain. Coppola makes it clear that the Mafia is big business, reaching across the globe like a dark hand.

Superbly acted by one of the finest ensembles in film history, including Pacino, De Niro, Robert Duvall, John Canaletto, Diane Keaton, Talia Shire, Lee Strasberg, and Michael V. Gazzo. In a master stroke, the director explores how absolute power corrupts absolutely, and we see Michael lose his soul, forever morally dead. I am not sure the editing of the film has ever been given credit for allowing the film to move as it does, to come to life, gently yet perfectly moving between the past and present within the film. Watching Michael grab Fredo and kiss him on the mouth, telling him he knows Fredo has betrayed him is far more frightening than seeing the actual killing of Fredo. Gordon Willis deserved an Academy Award for his sublime cinematography, but again, incredibly, was not even nominated. Coppola won the DGA Award for the film, and the picture won six Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, all to Coppola, with De Niro winning Best Supporting Actor. The greatest film of the 1970s and for me, the greatest film ever made.

Read More: The 10 Greatest American Directorial Achievements of the 1960s, Ranked