The freedom directors knew in the 1970s was taken away in the 1980s, as a result of several major bombs at the box office that left studios gasping for survival. One of them went bankrupt, undone by the constantly rising costs of Michael Cimino’s ‘Heaven’s Gate’ (1980), which all cost nearly fifty million dollars. Incredibly, it was not the cost of the film that ended the freedom of filmmakers, it was Cimino’s blatant disregard for the very fair requests and questions of the producers and studio executives; his arrogance, and terrible self-indulgence in his quest to make his film, seeming to have no regard nor respect for the executives funding his film. His behavior was repellent and earned him no friends.

The man had just won the Academy Award and DGA Awards for Best Director for ‘The Deer Hunter’ (1978) and overnight, everyone wanted to be in Cimino’s business. When his massive four-hour Western opened in late 1980 and was pulled from release the next day, he became a leper no one wanted to know. He could not get a job, he could not get a film financed, no one wanted him. He was finished in Hollywood, having bankrupted United Artists, having displayed unspeakable arrogance towards the studio chiefs. Ironically, I would argue Cimino’s direction of ‘Heaven’s Gate’ (1980) surpassed that of ‘The Deer Hunter’ (1978), but the staggering indulgence and length killed him.

With studios now hyper-cautious about spending, directors were forced to work with the budgets given, something that had been done before the seventies and would be done again. It seemed each of the major new filmmakers had a huge flop to contend with, some coming sooner than later. They learned how to work with a budget, those that did not, did not work. It was as simple as that.

Scorsese, Spielberg and Woody Allen had continued success in the 1980s but all around them, they watched their friends fall, sometimes rise again, then fall. In addition to Cimino, Francis Ford Coppola had the crushing flop ‘One from the Heart’ (1982), while George Lucas would produce the massive failure ‘Howard the Duck’ (1986). Brian De Palma would be in the era with back-to-back thrillers, ‘Dressed to Kill’ (1980) and ‘Blow Out’ (1981), the first a huge hit, the second a masterpiece piece but box office failure, throwing the director into a tailspin from which he would not recover until ‘The Untouchables’ (1987). Woody Allen maintained his film a year pace, sometimes two, managing to hold on to exceptional freedom from the studios because he made his films cheaply, actors dropped their price to work with him, and his pictures always were awards-bait.

New and outstanding filmmakers emerged, including the strange David Lynch, whose work almost always had a touch of the surrealistic within, his finest film being and still remaining ‘Blue Velvet’ (1986). Barry Levinson stepped behind the camera after years of writing and proved to have a delicate touch with actors in films such as ‘Diner’ (1982) and his Oscar winner Rain Main’ (1988). Robert Zemeckis, a Spielberg protégé, proved to have the golden touch with audiences as well as critics with his blockbusters ‘Romancing the Stone’ (1983), ‘Back to the Future’ (1985) and best of all ‘Who Framed Roger Rabbit’ (1988) which would win four Academy Awards and should have seen him nominated for Best Director. Bombastic, unsubtle writer Oliver Stone, the Oscar winner for his ‘Midnight Express (1978) screenplay, earned an Oscar for Best Director for his masterwork about Vietnam, ‘Platoon’ (1986), which came along at the right time, ending the comic mentality that had taken hold in that nasty war. Writer Lawrence Kasdan best known for his script for ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ (1981) directed a stunning noir as his debut, ‘Body Heat’ (1981), that was a powerful film, dripping in sexuality and darkness.

More and more actors began stepping into the director’s role, some were brilliant, some not. The best ones, Warren Beatty for ‘Reds’ (1981) and Clint Eastwood for ‘Pale Rider’ (1985) proved they could indeed have a second career with no issue, others such as Sylvester Stallone proved not.

Though the decade began with some tough news for directors and a grand loss of financial freedom, the best of them recovered just fine, working with what they had, creating art and box office hits. While it was happening, the 1980s were a frustrating time for directors and audiences, but in hindsight, it appears to have been a strong period for movies and filmmakers. More and more women were stepping behind the camera and doing excellent work; Randa Haines, Barbra Streisand, Kathryn Bigelow and Penny Marshall among them, but it was not until the 1990s that another woman would be an Oscar nominee for Best Director and still many years before a woman would hold a Best Director Oscar.

10. Martin Scorsese – The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

Scorsese would be here for sheer courage and patience in getting this film made, but being Scorsese, he is here because he created a sublime work of art. For the first time in film history, Christ is flesh, just a man, portrayed beautifully by Willem Dafoe; initially terrified by the voice he hears and what it is telling him, he gives himself over to it and becomes a leader of men though he knows he is doomed. There is a sadness about this Jesus we have not seen before, and it grounds him and makes him more accessible in some way. One of the best scenes comes with Pilate (David Bowie), who matter-of-factly condemns him to death.

The crucifixion scene became infamous because Christ, tempted by the Devil, came down off the cross to live his life as a man. He marries, fathers children, grows old, and, on his deathbed, returns to fulfill his destiny on the cross. Shot on an impossibly low budget for such a film, Scorsese managed to make a stunning, deeply felt religious film that brought to me true catharsis. Scorsese was nominated for an Oscar, the only one the film received.

9. Brian De Palma – Blow Out (1981)

Released in the summer of 1981, earned rave reviews, but no one went and watched it, preferring ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ (1981), ‘Arthur’ (1981) or ‘Superman II’ (1981). ‘Blow Out’ (1981) was rediscovered on home video and later Blu Ray. The beautiful Criterion edition has brought this superb thriller to an entirely new generation. John Travolta is astounding as a sound designer for B movies who accidentally records the assassination of a presidential candidate. His life, and that of the young girl in the car are placed in peril by the assassin, played with icy brutality by John Lithgow. Nancy Allen takes some getting used to as the sleepy voiced sex kitten who knows more than she is saying. In a race to save her, Travolta records what is happening and ends up with sound effects that will haunt his nightmares. De Palma keeps the film moving at breathtaking speed with split screens and fast, smart editing but never loses sight of the superb Travolta performance, his first real adult role. I love this movie.

8. James L. Brooks – Terms of Endearment (1983)

An astonishing debut that won Brooks, a veteran of TV three Oscars and countless critics awards for Best Film. It remains the finest film about mother-daughter relationship ever made, acted with beauty and fury by the great Shirley MacLaine, never better, Debra Winger, her equal, and Jack Nicholson as the rascal next door. The turbulent relationship between the mother and daughter goes from infancy to death, surprising you and never going where you think it is going. As the imperious Aurora, MacLaine is astounding, giving one of the screen’s greatest performances, while Winger, an earth mother, matches her every step of the way. How sad they did not tie for Best Actress because each feeds off the other’s performance, one cannot be without the other. Nicholson is superb as the guy who turns out to be precisely what the doctor ordered in his devotion to Aurora. The film won five

The film won five Academy Awards – Film, Director, Actress (MacLaine), Supporting Actor (Nicholson) and Adapted Screenplay. The actors swept all the critical awards that year, and Brooks made one of the best directorial debuts in film history. He has had films nominated for Best Film since, but he has never again been a Best Director nominee. He beautifully balances humor with tragedy here, creating a film that replicates life. You never see the bad coming in life, but neither do we see the good.

7. Oliver Stone – Platoon (1986)

When Oliver Stone, a decorated veteran of the Vietnam war and an Academy Award-winning screenwriter, made ‘Platoon’ (1986), that war had become a comic book for film, with films such as ‘Rambo: First Blood Part II’ (1985) and ‘Missing in Action (1984) trivializing the war. Stone’s grimly realistic film brought back the startling realism of being a grunt soldier on the front, hacking your way through the jungle in unbearable heat, being eaten by insects, and never seeing the enemy till they attacked. It was an alarming work, intense, electrifying and powerful, whip-smart in its dark brilliance.

Tom Berenger is frightening as the fearless marine who loves war, while Willem Dafoe his equal as a man seeking peace. They go to war, it seems, over the soul of Chris (Charlie Sheen), each tugging him into their world. Stone shot the film for six million dollars and it became a sensation late in the year, bringing in more than one hundred and eighty million dollars. Death comes suddenly and without mercy, bodies are torn apart by bullets and booby traps. The realism gives us an idea of what these young men endured, the abject terror they must have felt each and every day in the jungle. The film won the Academy Awards for Best Film and Best Director.

6. Sydney Pollack – Tootsie (1982)

What can go wrong directing farce? Only everything. When you are blessed with gifted actors with opinions, it can be even worse. That was what Pollack faced when he directed ‘Tootsie’ (1982), which emerged as the finest comedy ever made and the greatest, most insightful film made about acting. Workiwhip-smartscript, the director plunges us into the world of New York actors, constant auditions, classes, supporting one another, and often, waiting tables. When a difficult actor, Michael Dorsey (Dustin Hoffman) cannot get work, he disguises himself as a woman, Dorothy Michaels and lands a network soap, quickly becoming a huge star and spokesperson for feminism. Discovery means the end of his career, and when he falls in love with his co-star, Julie (Jessica Lange) he finds himself becoming a better man as a woman than he ever was as a man.

There is a breathtaking moment in the film where we lose Hoffman and Michael and accept Dorothy as a person. And when she is gone, like Julie, we miss her. Hoffman is a revelation in the film, the finest performance of his career and Pollack balances the farcical aspects with the truths within the film. There is no better film on the art of acting, and no greater comedy has ever been made. How did Hoffman lose the Academy Award? The scene between him and his agent, George, played perfectly by Pollack, is legendary.

5. Steven Spielberg – Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

The first ten minutes of this knockout adventure film are worth the Oscar alone, as Indiana Jones steps out of the darkness of the jungle to become the most iconic hero of our time. Defying booby traps set centuries ago, and certain death, he leaps, runs, jumps, and when needed, cracks his bullwhip to get the job done and manages to always stay alive. Harrison Ford was cast as Jones, after Tom Selleck begged off to do his TV Series ‘Magnum PI’ (wonder if he regrets that) and within five minutes of screen time, Ford owns the character. That said, he owes his career to Spielberg, who plunged him into a film in which he is always moving, always in peril, always saving the day, always with a sardonic comment or scowl on his face. It is an absolute delight. The film is based on the B movie serial films of the 1930s – ‘Jungle Jim’, ‘Flash Gordon’, ‘Tarzan’, even

The film is based on the B movie serial films of the 1930s – ‘Jungle Jim,’ ‘Flash Gordon,’ ‘Tarzan’, even Westerns; all kind of meshed together to give us Jones, an archaeologist who is also a teacher (secret identity), a swashbuckling hero, hell with a bullwhip, fearless with a gun, able to run, be dragged, just relentless in his pursuit of the Ark of the Covenant. The movie never stops; the characters are always in motion, yet the director manages to let the actors be their characters. Just a mesmerizing kick ass adventure film that does not let up till that mysterious ‘Citizen Kane’ (1941) ending.

4. Warren Beatty – Reds (1981)

Imagine, during the presidency of Carter and Reagan, having the immense courage to make a film about the American communist movement in 1915-1919. Unbelievable courage is what Warren Beatty had in making this sprawling though intensely intimate film about the radical writers John Reed and Louise Bryant. Reed would write the seminal book on reporting history, Ten Days That Shook the World, his eye witness account of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia. Beatty acts in as Reed, directs, produces and co-wrote this magnificent epic that is a remarkable study of artists and their passions. He creates a deep intimacy with the characters, and handles the epic scenes with bold confidence. The massive scene of the people taking over Moscow to the tunes of The Internationale are breathtaking, as are the scenes in the desert where suddenly camels are moving beside the train. Beatty is excellent as Reed, capturing the essence of a man forever chasing history. Keaton gives one of her most compelling performances as the complicated Bryant, who realizes only at the end what politics means to Reed. Jack Nicholson does a slow, searing, sexual burn as Eugene O’Neill, Reeds’ best friend and Bryant’s lover. Maureen Stapleton is outstanding, winning an

Keaton gives one of her most compelling performances as the complicated Bryant, who realizes only at the end what politics means to Reed. Jack Nicholson does a slow, searing, sexual burn as Eugene O’Neill, Reeds’ best friend and Bryant’s lover. Maureen Stapleton is outstanding, winning an Oscar as the anarchist Emma Goldman. Nominated for 12 Academy Awards, Beatty won Best Director, Best Supporting Actress went to Stapleton and the film won for its Cinematography. An American masterpiece.

3. Milos Forman – Amadeus (1984)

The music of the 1700s was opera, the popular songs of the day came from the operas of the time. Opera was the major art form of the day, the tunes from them hummed by the people roaming the halls of the palace to the peasants in the streets. Peter Shaffer’s great stage play was partly biographical about Mozart, partly imagined, the jealousy felt by court composer Antonio Salieri towards the much younger man blessed with God-given talent. Every young and middle aged actor in Hollywood auditioned for the film, every major actor made it known they wanted the part, including Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino for Salieri, Kevin Bacon, Tim Curry and Tom Cruise for Mozart. In the end, Forman decided on F. Murray Abraham as the jealous old composer telling the story in flashback, as he remembers it, while Tom Hulce won the plum role of the giggling, braying, arrogant, fascinated with bodily functions Mozart. So great was the old man’s love for music that he alone knew Mozart’s music was timeless and would be remembered long after he was forgotten, and in fact, as he grew older, he saw his music become extinct, while that of Mozart was revered and remained for ages. Forman gives the film an energy and bounce most period pieces lack (read: boring), which brings the time to life; it is alive, the streets are teeming with people, Mozart jauntily walks the streets, smiling, drinking, and we are there. The performances of the actors are stunning, just brilliant. They each came out of nowhere to give them and then returned to oblivion, never again coming even close to doing this level of work again. Mozart is treated, rightly so, as a rock star, looking closing at his wigs, they are all tinged with pinks and purples, set apart from everyone else, just like his music. The portrayal of genius might never be so accurate. The film won eight

Forman gives the film an energy and bounce most period pieces lack (read: boring), which brings the time to life; it is alive, the streets are teeming with people, Mozart jauntily walks the streets, smiling, drinking, and we are there. The performances of the actors are stunning, just brilliant. They each came out of nowhere to give them and then returned to oblivion, never again coming even close to doing this level of work again. Mozart is treated, rightly so, as a rock star, looking closing at his wigs, they are all tinged with pinks and purples, set apart from everyone else, just like his music. The portrayal of genius might never be so accurate. The film won eight Academy Awards, including the second for Forman and Best Picture. His greatest accomplishment is giving the film life, absolute life, and that life is through music. Does Mozart ever look as alive as when he is conducting that which he has composed?

2. Steven Spielberg – E. T. : The Extraterrestrial (1982)

This dreamscape of a film about a child’s relationship with an alien left behind by accident is directed with sublime confidence and love by Spielberg. The many images he conjures throughout the film are staggering in their sheer beauty; that ride across the moon, the plant growing after the death of the alien signalling his resurrection, the tiny alien pulling Elliott (Henry Thomas) for a farewell embrace, the ship leaving a shooting a rainbow in its wake, pure movie magic. What is often forgotten and multiplies the accomplishment of the director is that the leading character is a special effect, a latex-created creature with eyes modeled on Einstein and voiced in post-production. Further, the performance he gets out of his child actors are equally astounding, in particular Thomas who should have been nominated for an

Further, the performance he gets out of his child actors are equally astounding, in particular, Thomas who should have been nominated for an Academy Award for his sublime work, the finest work by an actor under 12 I have ever encountered. In keeping with the time of lower budgets, Spielberg managed to keep the budget for the film to under ten million dollars, an extraordinary feat considering it is an effects-driven film. He had indeed learned much from his failure at the end of the 1970s. Nominated for nine Academy Awards, the film won four and though anointed Best Director by the LA and National Society of Film Critics, Spielberg again lost, though winner Richard Attenborough stopped on his way to the podium to tell him he should have won. No question he should have. One of the many times he should have.

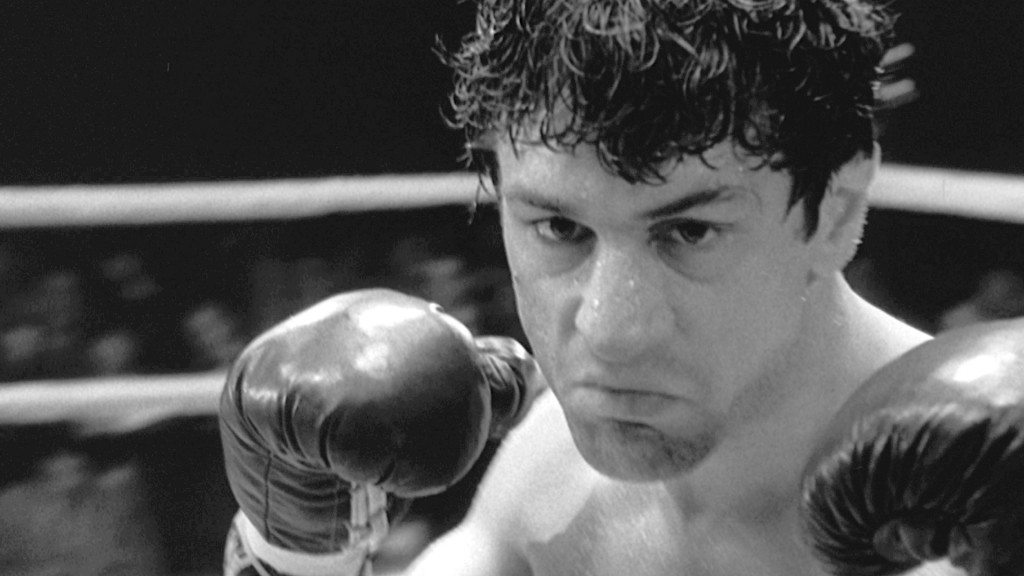

1. Martin Scorsese – Raging Bull (1980)

The opening title sequence hints to us what this film is about as we see Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro) shadow boxing in the ring before a fight, already at war with himself, forever fighting his demons, fighting himself. Scorsese had no interest in directing a boxing film, and I daresay he did not direct such a film, rather, he made the finest film set in the world of prize fighting, exploring what makes these men tick. What drives a man to whip himself into peak condition, put on gloves, a mouth guard and climb into the ring to beat the hell out of his opponent, before the other man does the same to him, that was what drew Scorsese into the story of LaMotta. He raged, both in the ring and out of it, which drove everyone away from him, his beloved brother, his first and second wives, his children, his friends, even his fans came to despise him for what he was. Insanely jealous of his second wife, the gorgeous Vicki (Cathy Moriarty), he would go ballistic over the slightest look she gave anyone or they gave her, leaving her a prisoner in her own life. We see LaMotta rise in the ranks, and throw a fight to get his chance at a title, which he loathes doing, sobbing afterward about what he did, until finally, he wins the middleweight championship of the world. And then we watch in horror as he begins a long descent, alienating everyone he loves out of his life, finally thrown in jail for serving minors in his bar and statutory rape, having sex with minors. De Niro is remarkable in the role, in incredible condition for the sequences of Jake as a fighter, fat and bloated, having gained eighty pounds for the scenes where he is finished with fighting. More so than any other director, Scorsese places us in the ring with the fighter, right in the thick of it, allowing us to hear what they must hear and see what they must see. As realistic as anything I have ever seen in a film, the scenes are powerful and visceral and as we watch LaMotta take a terrible beating, his arms outstretched on the ropes like a man crucified, we understand what boxing is to him, a way of punishing himself for the sins of his life. Shot in stark perfect black and white, the film is a dark masterpiece you might only wish to see once or twice in your life. Raging Bull gave us our first look at Joe Pesci as LaMottas younger brother, brilliant. A punishing, searing work of art.

De Niro is remarkable in the role, in incredible condition for the sequences of Jake as a fighter, fat and bloated, having gained eighty pounds for the scenes where he is finished with fighting. More so than any other director, Scorsese places us in the ring with the fighter, right in the thick of it, allowing us to hear what they must hear, see what they must see. As realistic as anything I have ever seen in a film, the scenes are powerful and visceral and as we watch LaMotta take a terrible beating, his arms outstretched on the ropes like a man crucified, we understand what boxing is to him, a way of punishing himself for the sins of his life. Shot in stark perfect black and white, the film is a dark masterpiece you might only wish to see once or twice in your life. Raging Bull gave us our first look at Joe Pesci as LaMottas younger brother, brilliant. A punishing, searing work of art.

Read More: The 10 Greatest American Directorial Achievements of the 1970s, Ranked