First off, I’d like to devote some time to honourable mentions and near misses: The unappealing Miko Naruse’s laborious Floating Clouds, When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, Yearning and the more forgivable Sound of the Mountain did not make it. I’ve tried left plenty of time to warm to his work but it continually fails to interest me, sad to say. Tampopo, Castle of Sand, the Man Behind the Sun, Angel’s Egg, Belladonna of Sadness and The Taste of Tea also sadly didn’t suit my cinematic pallet. To cut tidal flow on an over-abundance of Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu I did not include their superb Stray Dog, Scandal or Kagemusha; nor the demonstrably prolific Ozu’s I was Born But…, Early Summer, Late Autumn, The Only Son, The End of Summer, The Flavour of Green Tea over Rice and A Hen in the Wind respectively.

Keep in mind that this list is for the best films: So none of these movies actually quite pipped it to the no.100 spot regardless. I just wanted to acknowledge their quality amidst so many other gems. So too are Shohei Imamura’s solid but ultimately unsatisfactory Pigs & Battleships, The Pornographers and A Man Vanishes absent, along with Yoshishige Yoshida’s beautiful Coup D’état and Wuthering Heights, Kon Ichikawa’s humble Conflagration, The Heart and Ten Black Women as well as Hirokazu Koreeda’s touching After Life, Like Father Like Son and Nobody Knows… all of which have made me excited to seek out After the Storm when this is over. Finally, I’d like to take a moment to speak about the work of Sion Sono: Despite frustrated perseverance and desperate hope- I can’t say a single piece of his I tried was worth the effort. Cold Fish, Tokyo Tribe, Guilty of Romance and the execrably poor Love Exposure are all duds, not least of all the latter- which was the very worst film I saw on this journey through Japanese cinema. Unbearable.

With that out of the way: Let’s begin. Here is the list of top Japanese movies ever made.

100. Gate of Hell (1953)

A luxuriously outfitted period venture, Gate of Hell’s appeal lies in its gorgeous palette of designs. Directed by Teinsuke Kinugasa, most famous for his 1926 landmark A Page of Madness, it’s a tightly wound tale that takes about two tries to fully appreciate, especially for Western reviews unfamiliar with the honour-bound code of Feudal Japan- but rewards with a richly crafted twist and sinister hints at the supernatural menace to which it’s title alludes.

99. Lone Wolf and Cub Series (1972…74)

An odd contender for the king of comic-book franchises, Lone Wolf and Cub tracks an exiled executioner and his young son through a seven-part series of flicks all of which make up this spot on the list. Part III: Baby Cart to Hades and Part VI: White Heaven in Hell are the strongest in my mind- though each are worthy of a watch and newly available from the Criterion Collection as of this year. It’s a selection of warm character pieces with tantalizing action and humor to eclipse any formalities in narrative- all worth a watch and more than worthy of forging their own space here.

98. Ichi the Killer (2001)

Outrageous beyond outrageous, Miike’s fearless flurry of style undermines any need for substance, centralising a focus on depravity and excess from the word go and fulfilling its promise of pain and bloodshed to an extent few films on the legal side of the line can even comprehend. It’s gloriously goofy fun with a lick of darkness so extreme you have to take it seriously. I can’t help but respect Ichi the Killer for being so comfortable in its own absurdity- and whilst the titular character proves to be a clichéd bore, Miike finds enough momentum in the early stages to push through to the finish with me confused, perplexed and utterly fascinated by the experience every time.

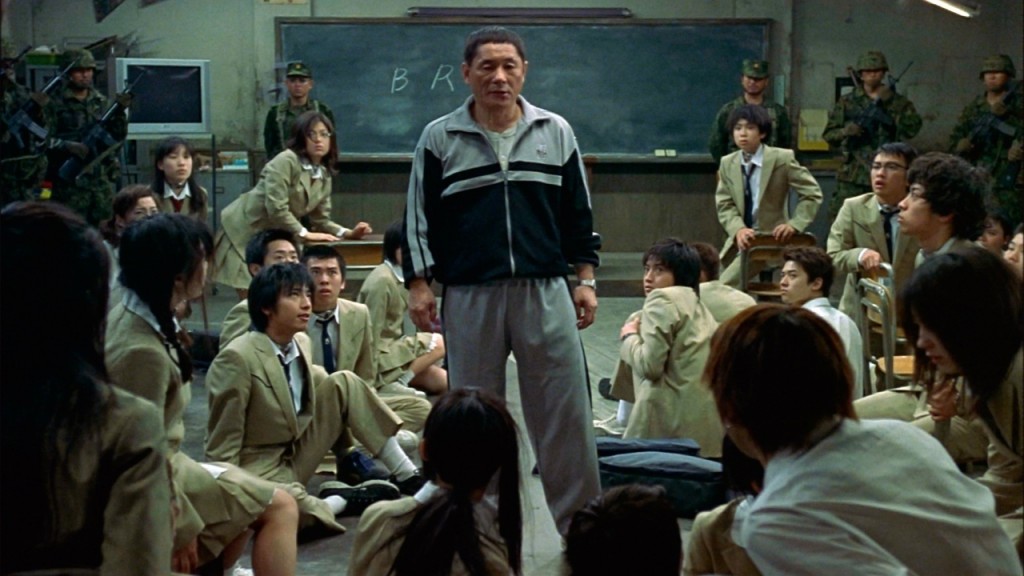

97. Battle Royale (2000)

Kinji Fukasaku, the man behind the crime anthology Battles Without Honour or Humanity, is an artist who here expresses a pervading quality so wonderful about wider Japanese cinema: Being unafraid of embracing genre film-making. Battle Royale is singularly designed as an uber-silly satirical comedy and whilst it hits humanist marks along the way, the rivers of splatter and impeccable comedic timing Fukasaku attaches to even the most morbid of situations make the flick an absolute blast. Takeshi Kitano’s turn is particularly notable, scrapping all notions of respectability for an all-out assault on wit and taste. Battle Royale is messy, that much is true, but the way it so tirelessly regroups time and time again for yet another attack on the sceptical is glorious. Without hesitation, Fukasaku understands the blunt weapon he holds in his hands and swings it at full force. The fact it was his final film lends a certain dignity to the man’s endeavours- a suicide mission striking at a funny bone you’d have to be comatose not to feel prickle at least once or twice throughout. Essential entertainment.

96. Godzilla (1954)

A classic monster film to rival the likes of King Kong and any one of Universal’s sterling original lineup, in scale at least. Godzilla doesn’t quite have the humanity and wit of The Invisible Man or the ferocious longing of The Creature from the Black Lagoon- but it is fun. Watching a big man in a deathly difficult suit traverse urban Japan is an engaging experience to this day, primarily for its inescapably humble charm. It feels in the moment and despite its rapidly dating effects it’s more than welcome to stay there as the relic of an era long since lost- and now is a better time than any to hope it’s masked lead Haruo Nakajima rests in peace.

95. Crazed Fruit (1956)

A fore-running founder of the Japanese New Wave, Crazed Fruit’s focus on the flame of youth finds its feet with a simple story that extends far beyond its humble parameters: Jumping the fence of two men in love with the same woman to reflect an impression of the post-war generation as a whole. These people are fierce, independent and desperate to prove themselves- scarred by the repeated desecration of their nation’s values. It finds a niche of storytelling that ricochets through social and political contexts- and represents the broad first steps of the New Wave. As this list continues, we will see that the long-lived movement forever ventured inward- either fascinated or frightened and in doing so finding a narrative not of nations- but of sexuality, perversion, violence, greed, supernaturality and psychosis. The Second World War may still lurk in these stories- but I find it intriguing that tackling it as openly as Crazed Fruit did was eventually met with focus, rather than explosion of theme.

94. The Life of Oharu (1952)

Our first flick by Kenji Mizoguchi, The Life of Oharu proves a classically moving character study that makes its protagonist reflective of the situation for women in post-war Japan, something Mizoguchi did admirably throughout his career. An expansive, complex dramatic piece that uses time to highlight the plight that quickly becomes its focus, Mizoguchi produces one of his finest works purely for the way he so humanistically buckles and breaks along with Oharu herself- the director moved by the adversity she faces. It is this relationship that bleeds straight through the screen that allows the film to elevate its drama beyond credibility.

93. Dreams (1990)

Written off the back of his own subconscious, Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams is a painterly portrayal of the inside of one man’s mind: Loosely comparable to Pastoral except lacking its New Wave sensibilities in favor of a more measured, calm exploration into Kurosawa’s nighttime wanderings. The resultant collection of vignettes reveal something raw and unique about the way life is filtered through the lens of our subconscious- and in this might just be the most honest film Akira Kurosawa ever made. A lucid, lovely little gem.

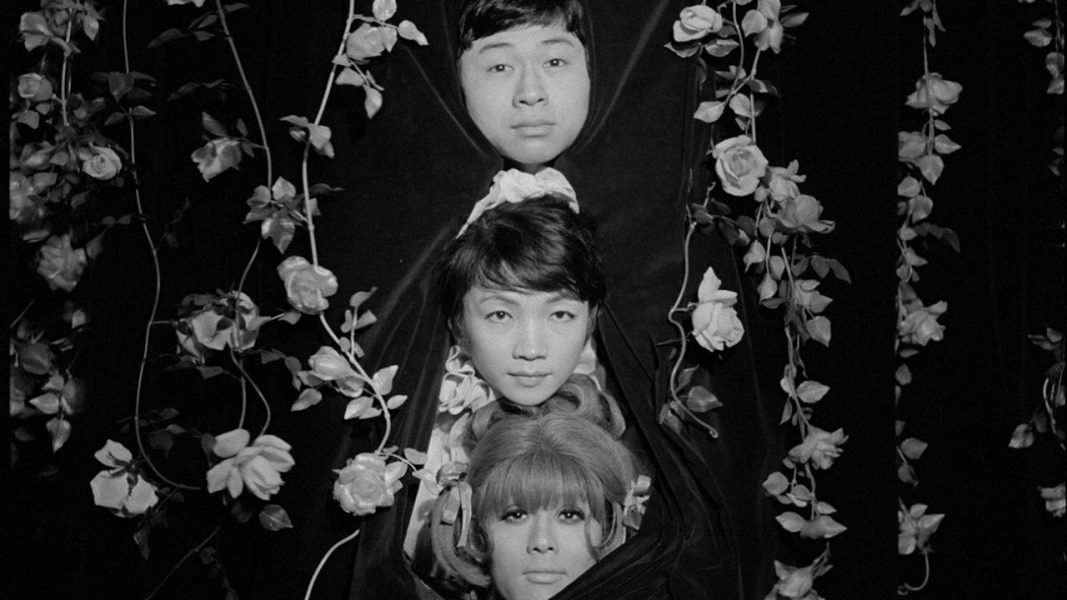

92. Funeral Parade of Roses (1969)

Director Toshio Matsumoto’s wide-open take on Oedipus Rex (perhaps the finest cinema has to offer), Funeral Parade of Roses marks a crucial watershed for alternative sexuality and gender-challenging imagery in Japanese cinema- and markets itself without the boundaries that have transformed the movement today. It is both a celebration and a criticism of human expression, understanding the confusion its characters face as well as embracing their own decisions with humility and joy. This critical conjecture of confliction is what defines Funeral Parade of Roses’ success and whilst I don’t think it’s the dearly departed Matsumoto’s crowning achievement, the way it championed its subjects in such an honestly flawed way is something we could all learn from today.

91. Paprika (2008)

Satoshi Kon’s 2008 flick is oft compared to Chris Nolan’s Inception– both based around concepts of dream invasion and coercion. I think the key difference that leaves fans split across a barricade is the fact that Nolan’s attempt holds greater emotional resonance and character focus- but all this gets bogged down in a tedious structure. Kon writes for 85 minutes and fills each frame with an intoxicating flourish of energy and colour- bridging between layers with such freedom and flexibility in storytelling that Nolan’s denser work simply cannot keep up. In the end both stand as solid examples of craft and ingenuity- but in terms of what I’d rather put on at the end of a rough day there is no contest. And to discover the vast array of creative powers Paprika holds in its arsenal, above just being a fun flavour of Inception- one only needs to grab a blu ray and hit play.

90. Ecstasy of the Angels (1972)

As an industry-wide movement, I feel the prevailing points of the Japanese New Wave revolved on the base of sex and violence. Both are intrinsic to life and art- elements that continue to carpet worldwide cinematic output- but I feel few movies tackle them in an engaged. Ecstasy of the Angels understands it’s own vulgarity. Director Kōji Wakamatsu’s continued dealings with such extreme subject matter afforded him the ability to hone depiction of brutally violent personalities- and the result is a crazed Sid & Nancy-esque exploration in anarchic loss of self, as well as a bitter tinge of romance thrown into the blender. Regardless of your view at the end, it’s a wild ride.

89. Ornamental Hairpin (1941)

Of all the pre-war artists whose memory is being abstracted by time, Hiroshi Shimizu is perhaps chief among those in dire need of rediscovery. Despite a bountiful Eclipse release by the Criterion collection (a pain to get a hold of and play anywhere outside of America), he seems ill-mentioned among the most important directors of the period and I absolutely hold to the belief that he should be championed amongst the best of them. Ornamental Hairpin was released as Japan was dragging America into the Second World War and yet it is laced with a hopefulness and simplicity that harkens to a more civilised age- or at least speaks to the pacifism Shimizu might have lived by from day to day- ignoring a conflict he deems barbaric and defying the outside image of Japan at the time. Without muddying this description in too many politics, Ornamental Hairpin lies among the finest features Shimizu crafted and it is his enduring minimalism that secures its beautifully understated resonance.

88. Ugetsu Monogatari (1953)

I don’t doubt being met with widespread vitriol for placing such a universally admired classic so low- but it has to be said that among countless thousands Ugetsu Monogatari still ranks among the 100 finest Japanese films ever made. I have a distinct distaste for Mizoguchi’s professed masterwork: A lingering wound of occasionally over-simple direction that often destroys his so often perfect artifice and ruins any and all of its previous effect. That being said, I’d be lying if not to mention how singularly fascinating this flick was for me when I was younger and, despite a disappointing series of rewatches in recent times, the magical moments where everything falls into place and Mizoguchi’s miraculously composed, cinematically engrossing and ultimately human attraction crept back into my veins. Ugetsu Monogatari slinks onto the list in part because it’s a seminal work, which is a shame because I pride myself in putting personal preference over status: But the crux of the matter is that I want to love it. Someday soon the affection might resurface and Mizoguchi’s masterwork will rise even higher. Time will tell.

87. Inferno of First Love (1968)

Tracing parallels in its conception squarely back to the likes of Breathless and Eric Rohemer’s meditative companionship in My Night at Maud’s from the ongoing Nouvelle Vague, Inferno of First Love is a quiet, beautifully absorbing observation of a couple taking their first steps together and the inviting, passionate, sullen, cold, often empty air that hangs around them as they attempt to harness the connection that the film’s title so boldly promises its audience. It’s a low-maintenance work of art that rewards patient viewers with moving human interaction.

86. Cure (1997)

The editing in Cure is deadly. It progresses to a point in which you want to look away, Kurosawa filling the audience with an implicit understanding of his movie’s mercilessness in the way it cuts through domestic routine and blood-spattered corpses as naturally as breathing; and it is this exceptionally cold, almost psychotic acceptance of death in life that makes me question its leading officer, Takabe, and just how hellish the situation concerning violence in Japan is to have grown so accustomed to brutal killings. Whilst it moves at a sluggish crawl that begins to undermine the breathless tension Kiyoshi Kurosawa has been able to breathe into the piece, Cure is still a more than worthy addition to his strong cinematic canon.

85. The Bad Sleep Well (1960)

Akira Kurosawa’s weakest Shakespeare adaptation remains one of his strongest films, loosely tracking the tale of Hamlet with a barb of corporate critique waiting in the wings. Held against other versions, despite its tangentially, BSW sits as a weak rendition of the revered play whose dialogue laden composition fails to capture the breadth and weight of Shakespeare’s drama- though it does cultivate a uniquely Kurosawan style of storytelling that adds an extra dimension to the source material and forges a deliciously compelling narrative beat. Altogether more modern and suspenseful than its inspiration, The Bad Sleep Well is a must-see for Kurosawa fans craving the skill and subtlety of his contemporary-set efforts.

84. Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)

Tackling Tetsuo with a weak stomach is like taking a bullet without a vest. Scrambled together with a mess of scrap props, cluttered sets and painful special effects- there is a vivacity to Tetsuo: The Iron Man’s pursuit of the unpleasant that makes it admirable. I have a respect for the cheapness its creators dealt in to achieve the most mortifying experience possible: Shocking with their pounding sound mix and grimy monochromatic visuals that cast what we know into the realm of enigma. Black and white paints even the most recognisable objects that make up Tetsuo’s world as horrific bastions of the unknown, crawling out under crevices and latching themselves onto us in order to begin a metamorphosis of mutation both violent and unavoidably sickening. It’s a piece of work past the point of concern for its audience’s delicate sensibilities- and that’s exactly what good body horror should be. Tetsuo: The Iron Man is without doubt one of the very best.

83. Black Rain (1989)

An oddly timed film considering it co-insided with Isao Takahata’s own treatise on the human toll of the nuclear bombs dropped at the climax of WWII and deals in similar themes, Black Rain’s inferiority to the wonderful Grave of the Fireflies in no way means it is to be disregarded. If anything, the legions of admirers that rightly collect around Takahata’s work should flock here too. Shohei Imamura’s first flick on this list, Black Rain takes a profoundly tragic, painstakingly personal look at the weight of the nuclear blast: Tackling survivor’s guilt, ostracision, grief, loss and acceptance of the event and its grave ramifications in a tactfully straight-forward style characteristic of Imamura that is it its own way just as striking and immediate as Hiroshima mon amour’s dreamlike lucidity.

82. Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937)

A formalist classic in the same realm as Kenji Mizoguchi’s venerable body of work, except that here equally revered director Sadao Yamanaka holds himself with a humility that everyone planning to enter the world of cinema can learn from. His other famous picture, The Million Ryo Pot, is a comparably calm, soberly composed and expertly dramatized tale- though I think the edge hits home for Humanity and Paper Balloons because it manages to make a wider statement about the essence of everyday life. The comfort of its playfully ambitious title echoes in every frame and whilst it’s not a flick I found intensely compelling or even patiently moving- there is something here that demands a watch.

81. Silence (1971)

Adapted from the same novel that was recently tackled by Martin Scorsese, Masahiro Shinoda’s Silence serves as a fascinating spotlight on the differences between Western and Eastern cinematic styles. Scorsese’s outwardly stoic, harsh tone is folded in favor of a far more humble outlook under Shinoda’s studious hand, allowing for a hair of remorse and sentimentality in an otherwise engrossingly naturalistic, stripped-down take on the book. A scene that highlights Shinoda’s prowess in developing a worldly atmosphere for his religious tale without the need for manipulation comes in the form of an old woman singing to a room full of people: Barely a word spoken resonates with the story at hand, nor is any further characterization conveyed- and yet it imbues the rest of the film with an inescapable vitality that so evocatively buckles under the weight of the anguish and desperation the priests and their disciples face. Understated and alluring, its humility tops the legendary Italian-American director’s piece for me any day.

80. Go Go Second Time Virgin (1969)

Immediately making matters difficult for itself, Go Go Second Time Virgin hits off its 65 minute runtime with one of several uncomfortable rape scenes. Fashioning a narrative out of the afflicted young girl’s serendipitous relationship with an equally youthful, disturbed killer who watched from afar- director Kōji Wakamatsu’s brief but vital opus defines itself by never attaching narrative convention to the pairing. Left to their own devices, revelations and conversations, the flick makes surprising use of its abundantly low budget with frequently effective composition in character of the Japanese New Wave- as well as a confrontational depiction of sexual violence far more engaging, dense and prescient than Nagisa Oshima’s infamous 1976 artistic misfire (and that’s putting it generously) In the Realm of the Senses.

79. The Sinners of Hell (1960)

Marked by a less than intuitive script and lackluster plot, The Sinners of Hell still manages to carve out its place on this list for its otherwise exceptional control of the artifice. Every frame is steeped in dank lighting and dabbled with a murky colour palette, occasionally punctuated by piercing stabs of red that serve as a subtle reminder of the agony to come. You see, Jigoku is a waiting game: A movie that bides its time in the monotonous real world before plunging into Hell. The excellent opening scene gives the audience a whiff of blood that tentatively tantalizes in every other scene until we are finally allowed to experience Tartarus for ourselves: A cavalcade of stunning setwork, glorious colour, excessive extras and genuine panic as the characters are given time to contemplate the consequences of their actions. So whilst tedious, the payoff it rewards us with warrants watching The Sinners of Hell at least once- for little in cinema matches its intrinsically conflicted, eerily lifeless vision of the underworld.

78. Twenty-Four Eyes (1954)

Following a young woman’s matriarchal place at the head of a class of schoolchildren and its implications on surrounding society, Twenty-Four Eyes is a feminist text that lacks the transcendental gender neutrality of something as masterful as Jeanne Dielman, but retains its place as an important work for strong central performance from Hideko Takamine and the Thiassos-esque narrative track that runs from 1928 to 1946 in a broad study of internal politics and the progression of perception across the years from peace to wartime.

77. Mr. Thankyou (1936)

Hiroshi Shimizu’s tactful meditation on our interaction, Mr. Thankyou follows a group of people on a bus and explores all manner of emotional character on the hour-long journey to their destination (thankfully veering away from a bus drive that would end far less smoothly a little later on this list). It’s a charming portrait of the poetry in everyday life that rises above so many more superficially ambitious films on this list for its ability to sit and talk for just over 60 minutes without missing a beat. A tiny little treasure.

76. Street of Shame (1956)

Teetering on the edge of an opus, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Street of Shame is one of the great swansongs- one that draws from all the man’s cinematic experience thus far in his career and assembles it into a timely, characteristically careful and remarkably human work. Living in a whorehouse during the twilight of prostitution’s legality in Japan, Mizoguchi constructs a beautifully moving tapestry of conflict and apparent ‘amorality’ given its true face that pierces perception and allows us to see past prejudice. Nowadays, audiences often relish in plainly anti-heroic or criminally unsound characters thanks to the flashy glitz of GoodFellas and other lionising, often cheerily sadistic portrayals of morally unsound characters. In 1956, particularly during a legal transition- such a film must have been unheard of. The women of Street of Shame are just trying to live- and that’s what makes their burden all the more heartbreaking.

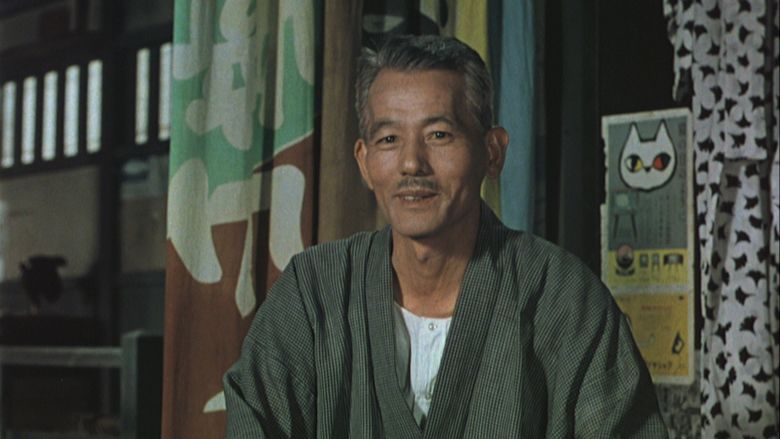

75. Floating Weeds (1959)

Rightfully regarded among Ozu’s greatest achievements as an artist, 1959’s Floating Weeds tracks a travelling troupe of performers and the family issues they face during their travels- particularly the reunion of previously separated parties that threatens to absolve the lucrative theatre company. Its just as powerful as Ozu’s best films but I do take issue with a measure of storytelling here, notably the structure. Held against some of the later Ozu films we’ll encounter here it can’t hold a candle to them- but at the very least it is a measure of how skilled an artist he was that Floating Weeds still manages to break the top 75 in luminously quiet, contemplative form. Still seminal.

74. Pastoral: to Die in the Country (1974)

Shūji Terayama’s Pastoral is a sublime exercise in oddity. It would be naïve for anyone to dub this particular branch of the bizarre ‘surreal’ because Pastoral is far less subtle than that: Packing its brief runtime full of absurdist comedy and fantastical imagery that harkens to a memory the director experienced in his future. The incomprehensibly of such an inspiration is little in the face of its plot and ideas- though as with his earlier work Terayama’s laxity of plot does not in any way detract from the experience he is attempting to provide- and if his magnum opus attempts to express the anger and passion of a disaffected youth then this is his own more personal follow-up: An exploration into an enthralling mind gorgeously photographed and warmly realised. It easy to make a film weird, but to then accentuate the impact it’s visual virtuosity with personality, technique and directorial ability is something the man achieves here. It’s really something to be seen.

73. Perfect Blue (1998)

A defining cry of talent from animator Satoshi Kon, Perfect Blue finds physicality in the internal struggle of a retired pop idol attempting to grasp her new identity- all wrapped up in the ever-evolving push of the modern world. Kon’s visual sensibilities lead to both superb and so sadly overdone cinematic moments- but I think the intoxicating narrative design Perfect Blue finds in the relentlessness with which its protagonist tortures herself and, in doing so, is tortured pushes it past any directorial hiccups. It’s a metaphysical piece that allows itself to make horror real- that pushes the boundaries of traditional animated features for something altogether more dark and disturbing for its bravery. Despite himself, Kon does not shy away from reality in his depiction of mental degradation- and that is what anchors the otherwise dated dilemmas of Perfect Blue to this day. A fascinating, often perplexing experiment of animation.

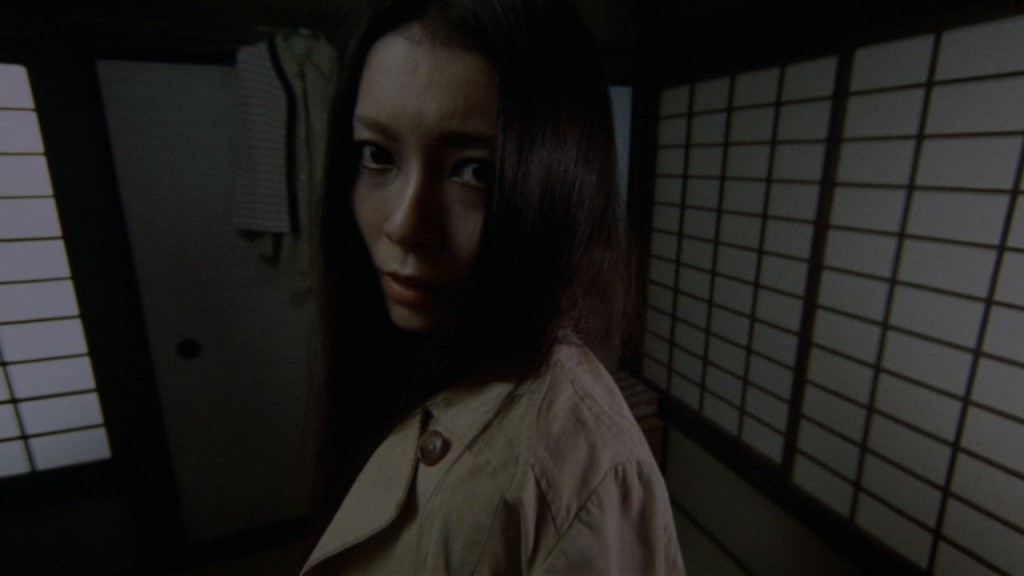

72. Dark Water (2002)

A direct evolution of the terrifying Ringu, Hideo Nakata’s Dark Water represents the director’s second and perhaps only other hit- and one that manages to bring his style even further. It’s graced with a maturity that escapes many J-Horrors, underpinning the power of it’s drama with a sly attention to poise and precision that lesser artists would be utterly unable to grasp. It’s pulsating pursuit of some unseen goal reverberates throughout every scene and fashions inevitability into a weapon not only of fear- but compulsion too.

71. Yûkoko: the Rite of Love and Death (1966)

Yûkoko: the Rite of Love and Death is infamous for a few reasons, namely because its director Yuiko Mishima also committed suicide through seppuku after a failed military coup. The man was the basis of Paul Schrader’s very best film, A Life in Four Chapters, and centres himself as a demonstrably fascinating subject here- making use of Noh staging and strong composition to profess his wordless message. The squeam-inducing special effects are hugely impressive for their time, simulating the act of Harakiri to startling effect and making for the perfect punctuation to Mishima’s patriotism. No surrender.

70. Akira (1988)

A shimmering, neon-laced landmark of Japanese animation and its infiltration of the international centre-stage, Akira marks a revolutionary point from anime and impresses even today in its glittering colours, cute futurism and amorphous, abominable title character’s grim transformation. Whilst the story structure is cluttered with side notes and unable to find a clear direction in which to thrive, the popping realisation of Akira’s action and more impressive feats of animation are what makes it so influential and aggressively engaging- searing screens with expressively crafted vignettes and transcending the slack-jawed stupidity of its progression for something genuinely spectacular. It’s vicious, dynamic and endearing- a worthy classic and a kick-start to a wondrous age of producing high-quality animation.

69. Sansho the Bailiff (1954)

It is at this point I have to confess: I have never liked the work of Kenji Mizoguchi. Despite trying several times to worm my way through his pictures, nothing has ever really stuck. Little about his work engages me and what is there on a written level descends into dullness once he so bluntly transplants it to the screen. Doubtless there is wonder to be found in the man’s work- but it continues to illude me. All of this in mind, I did at the very least find some solace in my re-watch of Sansho the Bailiff for this list- a film that had formerly left me frustrated with its waste of such powerful material. This attempt blossomed into a newfound appreciation of Mizoguchi’s iconoclastic approach, one that feels vacant in his earlier work. Its peppered with profoundly affecting scenes and whilst I feel the film is about 20 minutes too long- and could rise to the realms of mastery in a more succinctly moving space- it has at least made ground for the legendary artist on this list. Maybe years from now I’d put Mizoguchi’s work higher on here- one can only hope.

68. Onibaba (1964)

Our first film from Kaneto Shindo, Onibaba spins a story of distrust and deception- two thieving women influenced by a possessed mask that soon seeks its own agenda. The atmosphere of paranoia Shindo develops through his careful staging and jarring story is tantamount to the flick’s success- splicing in new characters and events to heighten the audience’s sense of trepidation along with that of his main players to fuel a uniquely parallel emotional connection. But I think, above all of this, Onibaba’s enduring status as a classic of Japanese Horror cinema stems from one shot: A single image that packs so much visceral energy into its paralyzing stillness that I was physically taken aback by it- discouraged from venturing back into Onibaba in fear of encountering that same terrifying presence. In the face of that one, perfectly haunting set of frames, the rest of the movie almost pales in comparison: But to discount it entirely would be to miss the point of such a controlled build-up, as well as its sensationally handled climax.

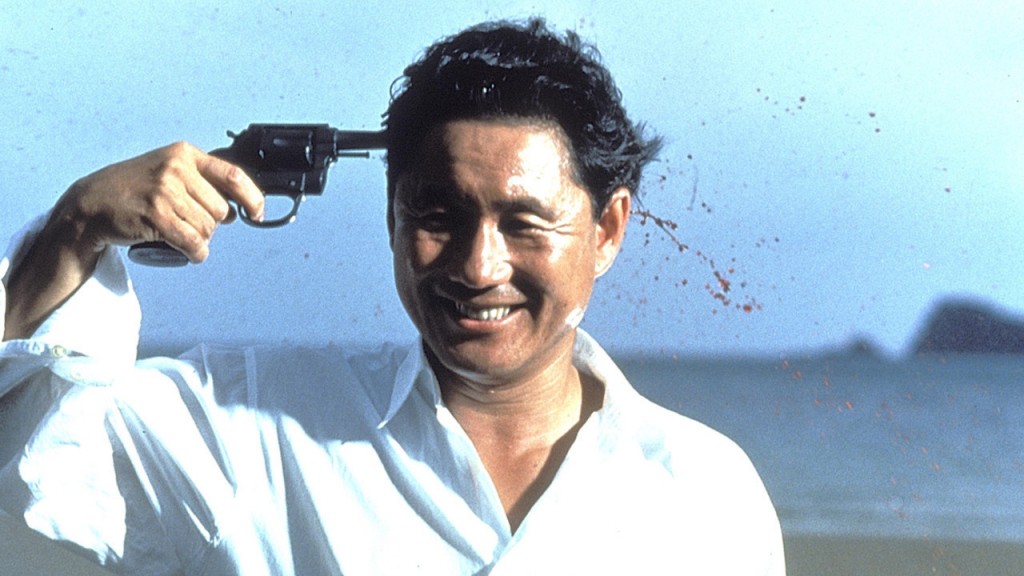

67. Sonatine (1993)

What is always impressive about the work of Takeshi Kitano is the way he lends levity to even the most gruelling scenarios. The near-missing Fireworks and Violent Cop are both in a way sharing their spot on the list with his opus, Sonatine, and all speak to his popularity in native Japan as a screen comedian and how those roots subtly seep into his cinematic offerings. Each frame he inhabits shines- despite his composition of dark and often brutal storylines. Playing with our perception of human morality and likability so deftly is what makes Kitano as fascinating a figure as has emerges from Japanese cinema in the last few decades- and proves, as was so adeptly said by Rodger Ebert after I saw Sonatine, that gritty crime studies need not sacrifice depth for engagement a-la Tarantino with his superficial monologues and mouthpiece ‘characterisation’. Kitano can do both.

66. Demons (1971)

New Wave watermark Toshio Matsumoto stunned 2 years prior with his exquisite Funeral Parade of Roses and 71’s demons maintains his sensory momentum with a starkly shot nightscape that plunges each image into utter darkness- only places and players illuminated in the nightmarish gloom. Other directors have experimented with this technique, perhaps an earliest notable example lying with Louis Malle’s interrogation in Elevator to the Gallows- but few have pushed it to such invasive effects- each shot piqued with an extensive sense of dread and, crucially, despair. No matter how close its protagonists come to escaping their supernatural attackers- nothing is ever safe. That, clearly, is exemplary existential Horror.

65. Still Walking (2008)

I think the towering shadow of Yasujiro Ozu can cast a sizable shadow over any dramatic film-maker, and the highly treasured Hirokazu Koreeda is perhaps chief among the afflicted. The man attempts to evade comparison by likening his work to that of Ken Loach, moreso than the Japanese legend, however such a likeness is inescapable and highlights several shortcomings in Koreeda’s method. Ozu invites you to sit down with his characters and gradually unravels the point of the story, whereas Koreeda sticks his camera in the same room as the drama and just silently observes. His style is a lot less direct, somewhat reminiscent of Taiwanese master Hsiao-Hsien Hou’s technique yet still even more detached.

All this in mind, Koreeda’s refusal to intrude does, however, lead to some powerfully intimate moments later down the line- where he begins to blossom as the characters allow us to bridge the six degrees of separation between their world and ours. Something as simple as a person approaching a piano, extreme disparity in focus underlining the importance of the scene, works wonders in giving the audience tiny, evocative glimpses into the minds of his characters. Indeed Still Walking is a bastion of hope encouraging the film-makers of contemporary Japan to fall into the fold of family drama and strive to imbue it with the same compulsion and impact as artists like Ozu and Naruse did all those years ago. With directors like Sion Sono on the scene, it’s a gift that people like Hirokazu Koreeda are still around to coast above the seedy underbelly and give us something so quiet and captivating in its portrait of suburban life.

64. Confessions Among Actresses (1971)

A brutally honest, characteristically open film- not dissimilar to the unforgiving inquisition of Winter Light– Yoshishige Yoshida’s Confessions Among Actresses follows the traumas that caused three women to commit to their craft- the director’s first film in colour and, fascinatingly: One that in this new, blushing richness of colour strips away a lot of his extreme camerawork for a drab, bare pursuit of the truth and its effect on these people. Revelation is, in its own way, a form of healing- and Kiju Yoshida’s Confessions Among Actresses works wonderfully as a debate on that idea.

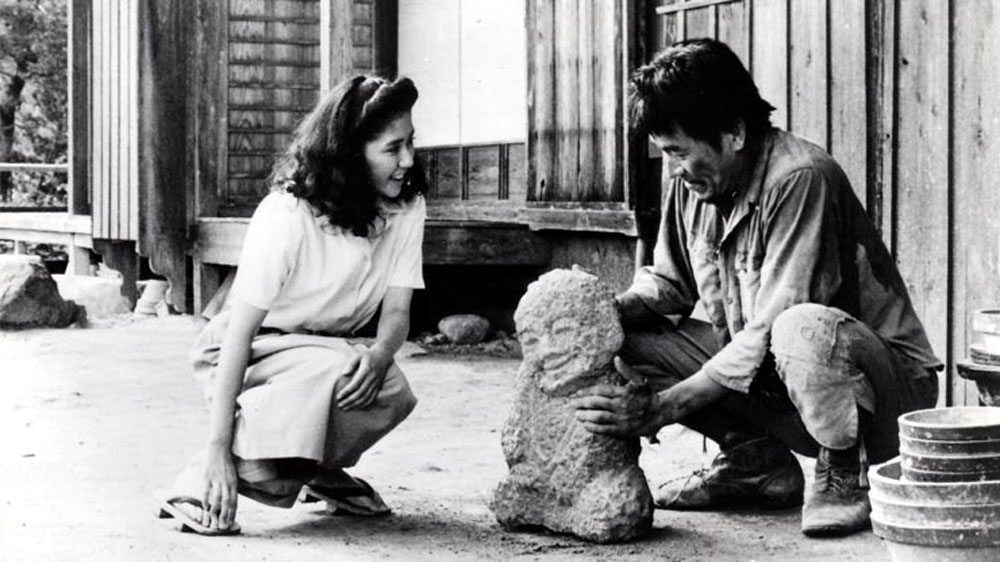

63. The Ballad of Narayama (1984)

The Ballad of Narayama represents perhaps Shohei Imamura’s most famous film, in itself a remake of an equally revered classic. What sets Imamura’s piece apart is his tactile approach to human action- fascinated with the grim responses and mutated psyches great emotional strain force upon a man or a woman’s mind. His earlier films handled such subjects much better, however I feel that does not exclude The Ballad of Narayama from standing tall among them. Its familiar folkish tale is just as careful a study of human behaviour and whilst it lacks the morbidity that gave his 60s work its bite- Shohei Imamura still delivers a satisfyingly compassionate, real piece of art.

62. Mandara (1971)

Mandara is, in its own way, one of the most cinematically fascinating films of the early seventies. Challenging but universally rewarding in theme, photography and the astounding mood it creates- it’s a peerlessly odd piece of work that might have made its way into the upper echelons of this list had I had time to dive deeper into its richly bizarre world. Sufficed to say: This little-seen New Wave gem is an absolute must.

61. The Tale of Princess Kaguya (2012)

The venerable Isao Takahata’s 2012 return-to-form after 1988’s stunning Grave of the Fireflies, The Tale of Princess Kaguya is just gorgeous. A family fable fit for any age, its’ absolutely beautiful style of animation harkens back to classical designs painted into a blanket of white- a back-to-basics ideal that has inspired properties in more than one medium since. The far-reaching aesthetic pull of Kaguya isn’t quite eclipsed by the story- but its luminous cinematic compulsion is still inescapably intoxicating from beginning to end and demands attention from any fan of animation.

60. Your Name (2016)

The most recent film on this list, last year’s Your Name is a revelation. Popular cinema in America can often be so lifeless and cynical, even its indie scene beginning to be attracted by fame more than artistic merit (not to discredit the obvious exceptions to this growing observation). I say all of this because having studied contemporary Japanese releases for this list, its thrilling to have a film as wonderful as Your Name be as successful in the mainstream as it was. Japan has been both swamped and gifted with a slew of animated features ever since Akira in 1988 and whilst the rough often swamps the diamonds beneath it- a film this strong broke through with ease. Without introduction or comment just see Your Name. It’s something with the heart and honest intentions we could all take a lesson from today.

59. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is an early bastion of animation titan Hayo Miyazaki’s sublime skill as an artist. The storytelling is exquisite- building some kind of sullen apocalyptic future as if in our own world with freedom of direction and gorgeous realisation of the land’s unique flora and fauna- all populated with a diverse cast of lonely souls who express the creeping recognition of their unwelcome world wonderfully. The first of many genuinely heartfelt, original and lusciously inspired works from Miyazaki.

58. Shall We Dance? (1996)

I think what separates Shall We Dance? from any other ‘life affirming’ flick is how earnest it is. Akira Kurosawa’s own treatise on fulfilment (or horrifying lack-thereof) in Ikiru is a sharp contrast to the harmless charm here- one that germinates naturally and slinks into our hearts, rather than clawing their way in through cynically driven plot-points. It’s a wonderful film- one that has been gifted such a high position for how joyfully believable its story is and how comfortable director Yoshikazu Suo is with his product. A delight.

57. Akitsu Springs (1962)

Kiju Yoshida’s big breakthrough, Akitsu Springs represents the dawn of something special within the realms of the Japanese New Wave. As early as 1962, Yoshida was able to bring the psychosexual focus of many Japanese films at the time to a head and plug its inner depths with impeccable accuracy- a fascination he would only continue to sharpen as time went on. A series of similarly fantastic follow-ups cemented him as a key member of the movement but for me it is Akitsu Springs that holds strongest as the proprietor of his cinematic genius.

56. A Wife Confesses (1961)

Our first film courtesy of the prolific Yasuzo Masumura, 1961’s A Wife Confesses is a crowning achievement of the early Japanese New Wave. Following a woman charged with the supposedly accidental death of her husband, it captures the waves of aggression, cynicism and diversion characteristic of the darker side of Japanese cinema at the time- except without any of its often bloody, brutal violence. What we have here is violence of the mind- shot through voices barbed with bitterness and watched by eyes baying for some poor, life-imprisoned case to compare their own misery to. It is the veiled morbidity of A Wife Confesses that gives a weighty snap to its societal bite.

55. Profound Desires of the Gods (1968)

Shohei Imamura’s longest film, Profound Desires of the Gods is also perhaps the movie that most fully exemplifies his style. Following the tense dynamics of an isolated colony and the burgeoning romance that blossoms in its wake, Imamura’s slightly off direction and permeating sheen of almost journalistic integrity allows for a fascinating document on native life, love and how we are inextricably drawn to our own desires- be that through a consciously shared primal urge, or some intangible implant sent straight from above. In the end Imamura’s principle question to me was hard to manage: Is it easier to accept that our gods are cruel, or that we are?

54. The Human Condition part 1: No Greater Love (1959)

The first in an epic trilogy of films, The Human Condition part 1: No Greater Love is a movie that would set the precedents for its follow-ups- a list of both strengths and weaknesses director Masakai Kobayashi would only have time to learn from in hindsight, never quite clarifying the perfect balance for his hugely ambitious piece. No Greater Love features several immortal moments, most notably an execution scene that lasts for 10 minutes and sees the seething wrath of the oppressed Manchu bubble beyond the fear all the guns and barbed wire inspire for something especially resonant to this day- as well as the end of an arc for several characters. It’s an overlong, oversaturated and ultimately ineffective film… but it’s also a masterfully handled examination of the toll of war. Imbalanced to an extreme, The Human Condition’s opening chapter finds solid enough ground to form a film neither execrable or exceptional: But one still more than worthy enough to tap into the top 60 here.

53. Throw Away your Books, Rally in the Streets (1971)

Throw Away your Books, Rally in the Streets is a rush of blood to the head. A vibrant, listless arrangement of disconnected vignettes painting a vivid picture of the Japanese youth’s detachment from old values. A rejection of formalism for something altogether more modern, futurist- sliced up into pieces and yet totally comfortable in its own incomprehensibility. It’s the creative nature of the industry made manifest in the minds of the young, resulting in a startling, alluring and often boggling batch scenes. Few films from even the Japanese New Wave can light that same rigorously rebellious fire.

52. Red Angel (1966)

Massively prolific master Yasuzo Masumura worked on a colossal 33 films just during the 1960s- and one of the highlights of his swelling oeuvre is 1966’s sublime Red Angel. Centred on a romantically engaged young nurse being thrust into warfare, Red Angel develops its gruelling world exceptionally well: Beginning with the legions of veterans netted with scars and spattered with their own blood and sweat on the operating table in a dingy, derelict complex- all before finally being thrown into the crucible of this deadly conflict. The palpable fear is a mark of Masumura’s lavishly impressionistic edge- and marks him as a defining, sadly overshadowed voice of the nation’s cinema during the 1960s.

51. The Man Without a Map (1968)

A woefully underseen entry from Hiroshi Teshigahara’s impeccable oeuvre, dutifully overshadowed by his towering body of work from ’62 to ’66, 1968’s The Man Without a Map sees the rigorously iconoclastic director transition from stark monochrome to alluring colour photography: Gazing out across the sprawling labyrinth of industrial Japan with a sombre, somewhat dull palette that so richly echoes the protagonist’s unsated desire for answers. The Man Without a Map runs in rivers of doubt and confusion, landing its detective in deep water for the smallest of incursions and rarely allowing him a second to breathe and take in the vastness of it all.

Teshigahara playfully urbanises the torturous pursuit of his protagonists with a world that denies catharsis at every turn, commenting on the unceasing uncertainty of modern life with devilish precision. He abandons the nuanced supernaturality and surrealism of his earlier work for a far more grounded piece that is as a result perhaps even more haunting than the Sisyphean agony of Woman in the Dunes or Pitfall’s unthinking, unfeeling advance of death. The Man Without a Map strikes us on our home turf and that is why it is so perplexing- so unnerving- and why it remains such a vital piece of cinema to this day.

50. The Insect Woman (1963)

Our fourth film thus far by venerated master Shohei Imamura, the somewhat more respectable side of Nagisa Oshima’s more dangerously excessive coin, The Insect Woman is an exemplary representation of why Imamura’s vision of sexual politics was always far more fascinating than that of his controversial contemporary. It’s a film of sumptuous visual control: Instilling its images with meaning and weight as well as delicious aesthetic power that bleeds so much meaning in monochrome- The woman’s daily life beset by a baying sea of black and white that turns so much to mystery, as in Tetsuo: The Iron Man. Its eerily prescient opening scene, whilst simple, sews the seeds of the Kafkan cage Tome (played beautifully by the deservedly honoured Sachiko Hidari) is placed in- and hints at the monstrous implications Imamura’s vicious title sets in motions. It’s difficult viewing, not in the least aided by Imamura’s issues with pacing- but remains truly vital cinema throughout.

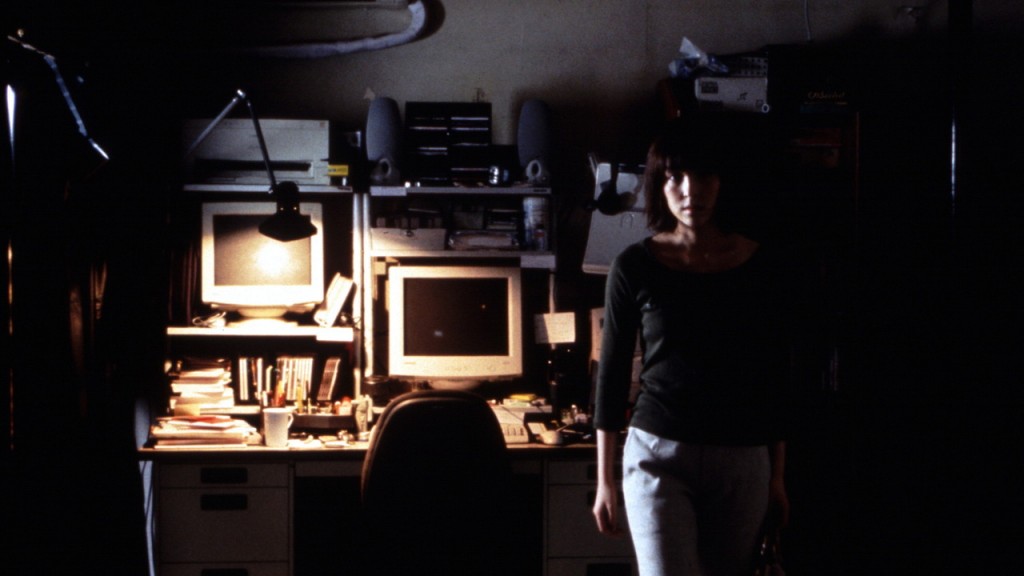

49. Pulse (2001)

Kiyoshi Kurosawa has steadily punched above his class under the weight of his familiar namesake with a fantastic string of ominous efforts- but none have quite eclipsed the overwhelming vacancy of 2001’s Pulse. Dripping with dread and making keen use of timely technological references without relying on them to such an extent that it ages the picture, Pulse is a superlatively scary take on modern haunting that makes far more effective use out of the familiar face of its Yūrei spirits than many more famous depictions of the pale-faced stalkers.

48. Battles Without Honour or Humanity (1973…1975)

Kinji Fukasaku’s multi-part crime anthology is The Godfather jacked up on every drug under the rising sun. Free from the oftentimes overbearing structuralism of Coppola’s perfectionist piece, Fukasaku films violence as jazz as he follows a ruling criminal family through the years- Often diving into gratuitous hyperstylised angles and editing to ensure the evanescent effect of his kinetic montage. Whilst it lacks complex character development, thematic resolution or even basic taste- there is something so blisteringly alive in Battles Without Honour or Humanity that I can’t help but love it. Each film adds to the last and collectively represent a zenith for populist crime cinema in 70s Japan. Little could ever come close.

47. Kwaidan (1964)

Masakai Kobayashi’s characteristically well-crafted Horror anthology, Kwaidan is a riveting dive into the mystery and malice of aged Japanese fables, the Medieval roots of J-Horror’s assorted cast of ghoulish apparitions and inescapable curses. The relentless lack of mercy or respite omnipresent in Japan’s thriving Horror scene is touched by the hand of a master here, resulting a visually sumptuous gem that manages to breathe alarming new life into otherwise dated stories. It is without a shadow of a doubt the finest Horror Anthology ever made: With the undiluted voice of an exquisite film-maker sounding off loud and clear that J-Horror is something to be feared. Decades later, we are still trapped in its ghoulish grasp.

46. Tokyo Drifter (1966)

Blazing maverick Seujin Suzuki’s damning slice of pop art genius, Tokyo Drifter goes off like a firework and lends more to its stylistic edge than even Quentin Tarantino and Martin Scorsese can claim today. The film’s fiery influence notably marks their editing and approach to action- not dissimilar to the way Goddard’s interminably excessive Breathless continues to shape the way we cut. To a much lesser extent does Suzuki’s piece slink into so many frames of modern crime cinema- but it is the stronger example of style ridding all need for substance: Its gunplay going off like a firework with zappy neon effects flaring crimson glory with each hail of gunfire. Made by a master choreographer at the top of his game- Tokyo Drifter is pulp cinema at its thrilling best. Electric and still a big barrel of fun.

45. Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

On the surface an inverse of Hayo Miyazaki’s universal-audience fables, Ghiblian icon Isao Takahata’s venerable Grave of the Fireflies stands as one of the most acclaimed animations ever made- heaving with emotional weight born of its masterful use of the medium. Case in point: Grave of the Fireflies would not be as universally appreciated or even notable if it were to have tackled said story in the realm of reality. Takahata’s lens, however, is drawn. His images are injected with an elegance and innocence indicative of childhood- one that compliments his protagonists’ plight perfectly. Whilst to some Im sure it comes across as a batant switch, few films have so adeptly utilized the art of animation to gracefully accentuate the power of their message. Cripplingly anti-war, Takahata’s expressively elegiac visuals does begin to clash against the overwhelmingly sad setup of the story: Letting a whiff of cynicism escape from its air-tight aesthetic hold- though it is of little consequence. Grave of the Fireflies is a haunting and often beautiful experience of wartime.

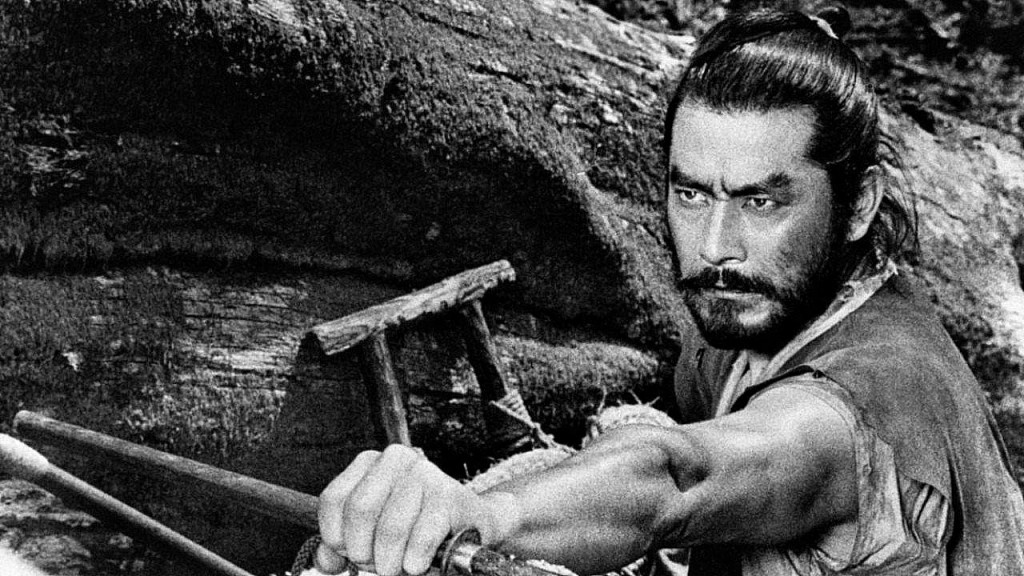

44. The Samurai Trilogy (1954-55-56)

An exquisite swathe of swashbuckling entertainment, director Hiroshi Inagaki’s deliciously appealing populist series is a landmark in action-adventure film-making- and quite possibly the finest trilogy to grace the sub-genre. Led by an as-always sterling performance from Toshiro Mifune and pockmarked with little glimpses of maturity, most notably at the end of the first film, Inagaki’s relatively inoffensive and incomplex narratives are buoyed on as sharp and exciting a grasp of cinematic action as the 1950s have to offer. His movement of the camera is thrilling, directing actors with a ferocity and vigour that aids the trilogy in overcoming its storytelling dry spells with the addition of a thrilling swordplay sequence. It’s nothing special on a dramatic front- but boasts enough passion for the craft and surprising soulfulness in its successes to warrant such a high placement. Vital viewing for fans of adventure cinema.

43. The Burmese Harp (1956)

Kon Ichikawa’s breakout piece about a Japanese soldier slipping into the country he once occupied and attempting to find peace in the pain of a post-war world, The Burmese Harp has drawn understandable criticism for its often blunted depiction of war: More dancing platoons and facile plot-point movements than a full, engrossing take on the time. Paradoxically, I think what helps The Burmese Harp overcome these issues is the heart behind them. Despite his abundantly controlled storytelling, Ichikawa weaves beautiful imagery throughout the film- gracing each scene in at least one frameable tableau that whilst contributing to the static sophomoricism of his direction does effectively manage to convey the mood- most notably in a sequence where death-driven soldiers are cut down by mortars and our hero wakes amidst a bloody sea of corpses: With inspired shots more akin to the stunningly tight composition of Rembrandt than any regular wartime affair. Its simplistic in a sense, but its weakness never overshadows the collective impact Ichikawa’s illuminating photography and staunch humility creates.

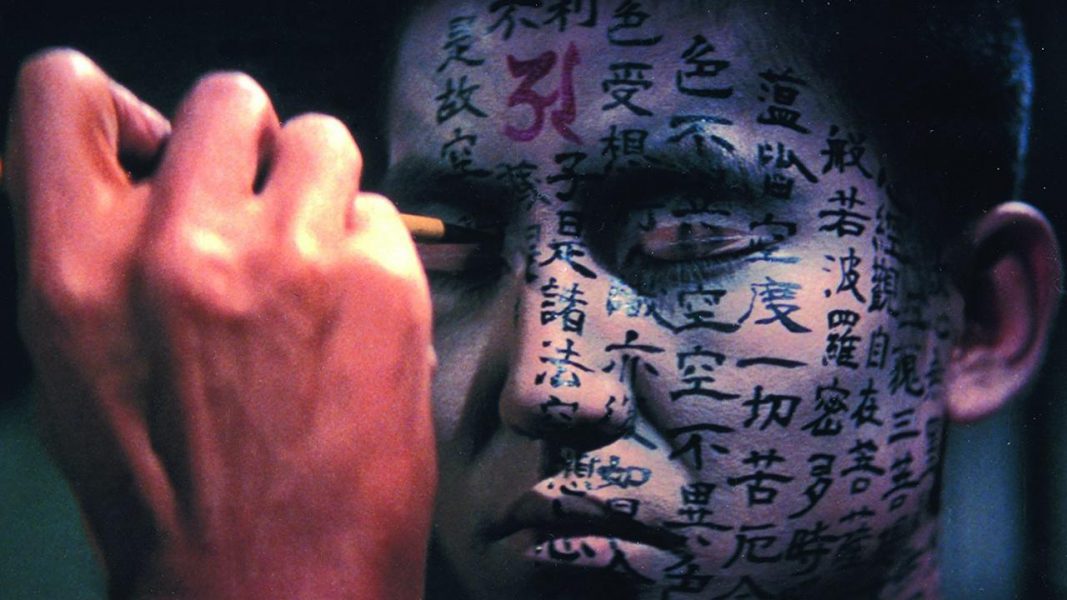

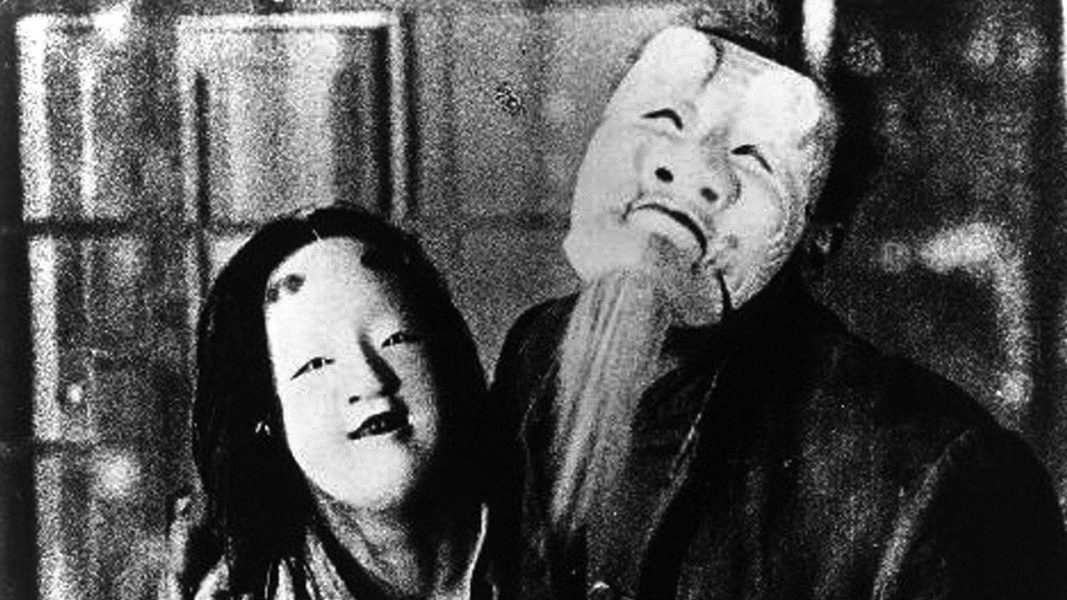

42. A Page of Madness (1926)

The earliest piece on this list, A Page of Madness is a staple of silent Japanese cinema for its resounding aesthetic voice: A piece that has informed the insanity and bristling creative spark that fuels the most wondrous works of their industry even today. Its portrait of an asylum lacks the nuance or profundity of something like Titucut Follies or even the humanity of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in fictitious form- however the transcendent takeway from this 1926 milestone is a widened appreciation of Japanese pre-war cinema outside of dramatic titans like Ozu, Mizoguchi, Yamanaka and Shimizu. What we have here is a source of their still-running river of cinematically challenging, stylistically provocative and intentionally dangerous pieces of work that is all the more fascinating with this gaggle of tragic artists in mind.

41. The Hidden Fortress (1959)

George Lucas’ infamous little franchise Star Wars was built off the back of The Hidden Fortress, with A New Hope stealing everything but it’s settling from this exceptional adventure tale. It’s a shame to see this ‘unofficial remake’ get away with murder, crushing Kurosawa’s flick under the weight of its colossal following- because The Hidden Fortress is a far worthier classic flick than Lucas’ series could ever claim to be. Packed with exciting action, hilarious characterisation and a strong visual flair customary of even Akira Kurosawa’s most middling efforts. All this in mind, I don’t begrudge Star Wars for this- just wish that Kurosawa’s brilliant piece of work was held in the same breath.

40. The Human Condition pt 2: The Road to Eternity (1960)

The battle-bitten piece of Masakai Kobayashi’s epic trilogy, The Road to Eternity serves as a sizable Japanese wartime epic fit to contest any Saving Private Ryan, if not quite as dangerous as something like Sam Fuller’s The Big Red One or even Steel Helmet. It retains the messy ethical obsession of The Human Condition part 1: No Greater Love but manages to build upon it with visceral combat experience and a measured, consistent approach to its characters that is underlined by their life and death in a deadly part of human history. As with each proceeding segment, The Human Condition comes closer and closer to achieving its namesake and whilst part 2 does not realise this ambition- it does at least try. More than we can say for most any film of the time.

39. Heroic Purgatory (1970)

Immediately incomprehensible, expressive and visually perplexing: Heroic Purgatory is a perfect primer for Yoshishige Yoshida’s exceptional filmography. His gorgeously alien aesthetics are oftentimes disorienting- each shot bending our relationship with space, each cut fragmenting time not dissimilar to the frenetic memory-inspired narrative of Alain Resnais- and in all honesty making the plot of Heroic Purgatory in particular genuinely difficult to both follow and understand. His fragmented storytelling technique puts even further strain on less open audiences’ desire for a totally cohesive narrative experience- but the indefinable delights that lie within Yoshida’s warped world do justice to their precedent over tightly structured storylines. To describe Heroic Purgatory would be impossible. To not recommend it purely because of its own impossibility- would be a crime.

38. Intentions of Murder (1964)

Shohei Imamura’s bleak triptych of Pigs & Battleships, Intentions of Murder and The Pornographers hit its uncontested peak dead centre with a film that observes with perilous detail the plight of a woman flirting between a degrading relationship with her husband and an afflicted affair with her rapist. The latter’s first encounter and the scene that directly follows it are beautifully succinct examples of how sublimely ugly Imamura’s worlds can be- and how human contact can often drive his characters to extremes many might attempt to discredit as unacceptable. In truth, Intentions of Murder’s cruel but honest study of oppression and some sick freedom through carnal expression manages to reflect just as accurate a portrait of any one of us in the same situation as his best films.

37. Assassination (1964)

Masahiro Shinoda’s double-release year in 1964 predictably saw two of the finest films the country has yet produced, the latter of which was Assassination. A shining example of comfort in scale, Assassination weaves a thematically unambitious drama that draws enough out of its simple story to regarded amidst the finer films on this list: As gorgeously lit and photographed as any film of the mid-60s with action as precise and powerful as you would expect from the stables of Shinoda. It’s underplayed mimicry of mental state as wild rumours about the target are quashed and quelled all around form a narrative that revels in its moments of unpredictable incomprehensibility- swiftly switching from reality to the past to leave both the audience and several apprehensive groups of would-be killers on the razor’s edge of triumphant victory and assuredly deadly defeat.

36. The Naked Island (1960)

Kaneto Shindo’s stoic examination of a quiet country life, The Naked Island contains almost no spoken dialogue- shifting the focus entirely to its images to tell its story or, more accurately, to create its _feeling_. Shindo’s iconoclastic approach to filmmaking leads to some beautifully resonant pictures throughout his filmography but whilst Onibaba and Kuroneko’s images enhance their narrative in small pockets of visual inspiration- The Naked Island is 96 minutes of essential photography. It weaves together in a way that would make Bergman blush, cultivating a mood and allowing it to blossom into something universal and affecting. The tranquillity and tribulation Kaneto’s little family of islanders face every day, almost like an oddly optimistic inverse of Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse. What it lacks in that film’s crushing power, Shindo instead develops into a ritualistic celebration of human endurance and the natural beauty such effort can bestow. Endearing, enlightening- and an impossibly absorbing little experience.

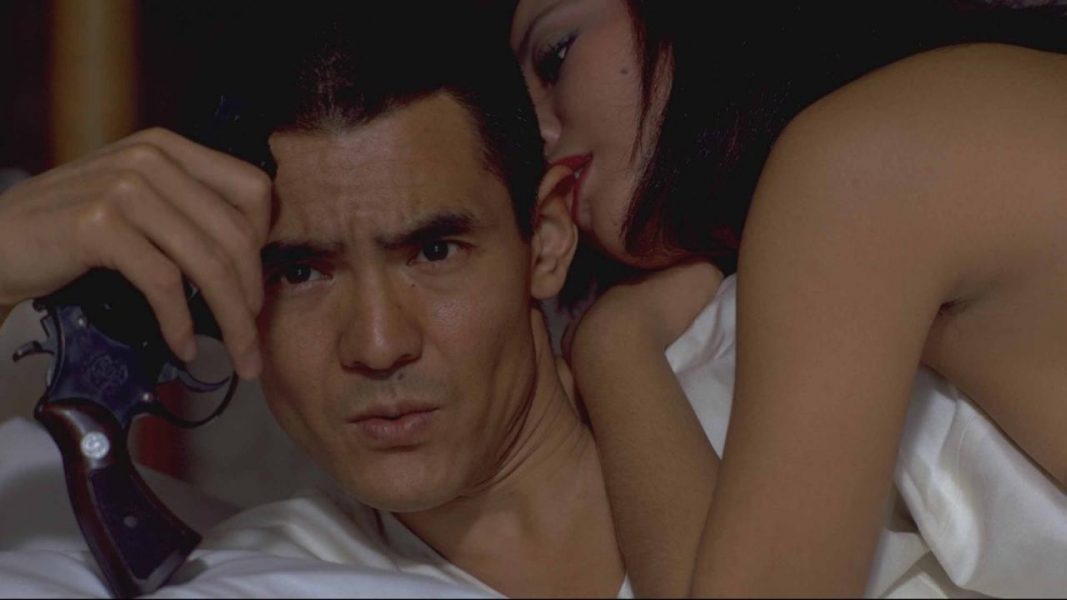

35. Branded to Kill (1967)

If the aforementioned Sejiun Suzuki would hit his stylistic peak with 1966’s Tokyo Drifter, a film so reviled by his producers that they damned his follow-up pictures to tighter budgets and sapped away any chance of him using colour, then Branded to Kill would become his creative zenith- and a perfect example of art through adversity. The man’s electrifying magnum opus, Branded to Kill follows a contract killer attempting to illude an even deadlier assassin whilst blasting his way through legions of goons and a lightningrod romance. Its forever sharp without losing its grit, tentatively reaches into more dramatically ambitious territory and still manages to pack settings full of faceless baddies for our anti-hero to gun down in droves. Branded to Kill’s style still managing to search for meaning, no matter the result, is what marks it out above the rest of the pack.

34. The Sword of Doom (1966)

Action maestro Kihachi Okamoto’s stylish pilot for a sadly cancelled trilogy, The Sword of Doom is the ultimate cinematic catharsis. It’s an expertly choreographed display of fiendish swordplay as leading legend Tatsuya Nakadai faces off against Toshiro Mifune and an endless horde of nameless goons all hell-bent on demonstrating just how deadly the titular weapon can be. Tens fall before the blade, most notably in the flick’s gloriously reckless unresolved final scene, and whilst it’s devotion to storytelling and character is tangential at best- the atmosphere and directorial bravado throughout saves it from becoming just another action highlight reel. Well worth seeing through to the bitter, bloody end.

33. Hausu (1977)

As high a compliment as someone can pay a weird movie is that it stays weird. Many of us have dubbed something strange because we are uninitiated- only to find that it’s supposed oddity pales in comparison to later cinematic discoveries. Such is the way of our path through film- as is this a very long-winded way of stating that Hausu is totally mental. Constantly harried by a sometimes inspired, often grating but always insane background score and filled with scenes of schoolgirls battling possessed watermelons, being eaten by killer pianos and escaping a ghoulish phantom cat hell bent on cursing every soul that crosses its threshold. Basically, it’s Ju-On but with the self-awareness and dizzying creativity to go the whole way on style alone- foregoing the background mythos storyline that so often mars haunted house stories with an absolute devotion to dizzying artifice. The resultant experience is a glorious blast-furnace of fun.

32. Ikiru (1951)

Akira Kurosawa’s much-touted portrait of old age, Ikiru runs as a staunch parallel to Ozu’s own work on people in their Winter years- losing his minimalist direction for Kurosawa’s far more direct, intense work. The result packs a punch: Several scenes licking with kinetic feedback solely through the strength of their images and the silence or swells of sound that accompany them. I think Kurosawa’s voice contributes little new to the exceptionally strong canon of cinema about ageing and generally fails to hit the revelatory heights of Wild Strawberries or The Life & Death of Col. Blimp despite their comparative lack of cinematic immediacy- however none of that detracts from the stunning resonance of AK’s work here.

31. Blind Beast (1969)

An incomparable exploration of sensuality and physical essence, Blind Beast tracks the relationship between a blind man and a woman he takes captive, trapped in a laboriously designed labyrinth carpeted in sculptures of the human form- with walls covered in eyes and lips whilst the floor is netted with an inavigable tangle of limbs. It’s surreality and intriguing premise are not windows into any truly dense thematic ground, though director Yasuzo Masumura does manage to externalise the relationship of lust with longing far better than the consistent knife-edge of failure Nagisa Oshima so often slips and slices himself on. For more contemplative pieces on sexuality, Yoshishige Yoshida is an essential artist- but to deny Masumura’s wholly unique vision here would be criminal- regardless of its lacking substance. Instead, he fills his film with gorgeous sets and aching feelings that claw at the characters. On a stylistic front, Blind Beast absolutely soars.

30. The Human Condition pt 3: A Soldier’s Prayer (1961)

Masakai Kobayashi’s devastatingly powerful conclusion to his ten-hour-trilogy, The Human Condition part 3: A Soldier’s Prayer serves as a culmination of everything Kobayashi has been developing throughout, equal parts impactful and overwrought- as with the other pieces. It’s a shame that the series never quite overcame the limp length of the book, nor the forced humanism that can occasionally stunt the otherwise strong form of its director: However without these stilted moments we would never have been gifted with an overwhelming collection of beautifully realised scenes that could have made a masterpiece all on their own. A Soldier’s Prayer is no more delicate than its predecessors- however that sense of an ending hangs over Kobayashi’s work like a weary dawn- keen to take the new day with a renewed stock in the Japanese film industry. Both a towering triumph of epic cinema and, more importantly, that final step through the gateway of fame that afforded Kobayashi bountiful artistic freedom for the following decade. The result is, as we shall see, more than worth a few hours of practice…

29. Double Suicide (1969)

An alarmingly eerie exploration of the creative process, Double Suicide sees a wood puppet play staged with the intention of its two leads ending themselves brought to life- with shadowy figures prowling the stages to progress their mock-narrative. A feverishly scary tale when the façade falls down and its nightmarish puppeteers exact their next moves- often morphing the sets in conjunction with Masahiro Shinoda’s shifting camera to form a hideously contorted sense of space. Outside of its multi-faceted artistic device, the plot of Double Suicide is relatively conventional and fails to find any profound ground- but that is perhaps what assures its success: Shinoda’s careful probing into his own creative block as prying demonic hands tug at the edges of his vision to make it more precise- as well as derail its intentions entirely. Be they a representation of his inner struggles or a workforce the director is failing to co-ordinate- the two-fold conceit of Double Suicide transcends its mediocre fable for a cinematic experience deserving of the top 50 and more than exemplary of Masahiro Shinoda’s colossal talents as a film-maker.

28. Ringu (1998)

Whereas the somewhat similar Ju-On suffocates under the strain of its own vacant tedium, Ringu’s emptiness is its deadliest weapon. Director Hideo Nakata’s seeping sea of silence pervades and invades each passing scene, highlighting each noise with the heightened intensity of a fear-fuelled person pulsing with adrenaline- no matter how mundane the scene. And so relevant sound counters like the phone ringing slice through the silence with uncompromising ferocity. There is no escape from Ringu in any corner of your mind. No matter where you run- as soon as you will hit play you are merely prolonging the inevitable. After all, what could be more terrifying than death confirmed by our own inescapable curiosity?

27. Kuroneko (1968)

Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko feels like a blistering mirage of Horror movie composites strewn together for a perfectly demonic vision of absolute nightmare. The complex moral dilemma simmering below the surface is a fresh take on those unstoppable spirits Japanese Horror media has been banking on since the beginning- forging an intrinsic narrative that overcomes the roughness of Shinoda’s earlier Onibaba to form something special. It’s a seductively shot, aesthetically engaging work that bridges the gap between reality and sinister fantasy with a distinctly compassionate eye- despite the bristling rage of its subjects. Not just a definitive J-Horror film- but also a classic of world drama in the late sixties.

26. Spirited Away (2001)

There is little in the way of animation that can fully compete with Spirited Away, at least in a creative sense. The film is overloaded with a stunning sea of unique designs and memorably crafted characters that all move and speak as expressively as the leads. The detailed universe Hayo Miyazaki managed to craft does, in my mind, vastly outweigh the characteristically odd storytelling and pacing of his work- not dissimilar to Akira in that it jumps forwards and backwards in progression at random intervals for the sake of eking out another act’s worth of material; though the listless danger Spirited Away finds itself in does at the very least allow us to soak in its vivid creations for a little longer.

25. Death by Hanging (1968)

I’ve shot petty little remarks at acclaimed director Nagisa Oshima throughout this list and understand the infantility of such a stance: But I only do this because this genuinely talented filmmaker is so often drowned in obsessively oversexualised cinematic output. Imamura’s comparably confrontational string of early work is effective in its underlying commentary on human emotion- but with Oshima so little is left to the imagination I begin to believe that there is nothing behind is frustratingly inept work. That is, to say, with the exception of 1968’s brilliantly bizarre Death by Hanging. The story of an executee that refuses to die, Oshima uses his crass but nonetheless perceptive lens to highlight a slew of social issues, governmental failures and human expressions- all wrapped in a constantly hilarious farcical comedy with a confident self-awareness a filmmaker as frequently mucky as Oshima had previously seemed so far removed from. Not before or since has he managed to match this inspired shot at capital punishment, which is a shame- but at least we got to see him soar at least once.

24. A Fugitive from the Past (1965)

Tomu Uchida’s A Fugitive from the Past is, in a word: Exceptional. The surviving films of its competent enough director are simply incomparable to the work on display here, speaking to some kind of serendipitous lightning in a bottle as Uchida was gifted with exactly the right story to fulfil his promise as an artist. A Fugitive from the Past looks into violence and self-inflicted grief in a way few films can- measuring both against the sand of time as it trickles down and more characters come close to delivering divine retribution onto our protagonist- a uniquely challenging character to both root for or against as he attempts to escape the bloody path of violence he carved through Japan in his early years. I find that A Fugitive from the Past is so singularly powerful and even possibly profound in its resolution that I should say no more other than, of course, to see it as soon as possible.

23. Pitfall (1962)

Hiroshi Teshigahara’s startling feature debut, Pitfall blends genres with the confidence and precision of an aged master- much less a director who had only ever handled documentaries prior. Whilst he somewhat struggles to keep his story compelling for the full 97 minutes- what Pitfall offers outweighs any issues with its narrative execution. Playing with our perception of reality through mixing murderers, phantoms and surreal imagery- Pitfall is frequently terrifying as its many characters desperately attempt to fend off their unstoppable attacker: A normal man clad in a white suit brandishing a switchblade. The humanity of Teshigahara’s ghoulish killer acts as the first of many social commentaries his works make in image alone- never sacrificing time or credibility to pushing a point home. Absent of its leftist leanings, Pitfall retains its power as a harrowing cinematic experience: Featuring several shocking scenes that speak to the clarity and craft of Teshigahara’s method as he injects even the most singular moments with a vast range of emotions that so freely dance around eachother- dovetailing from humour to horror in a heartbeat. Few debuts have been as meticulously aware of their master’s career path.

22. Tokyo Twilight (1957)

Yasujirō Ozu’s final black and white film, Tokyo Twilight’s tolls as both a contextual elegy to the man’s monochromatic outings, as well as perhaps his murkiest feature. Ozu’s notable shift away from his own 360 degree rule to instead sit behind characters, their sullen faces replaced with an overwhelmingly blank, cold head of hair is a masterful departure from his characteristically involving blocking and composition for a far bleaker affair- one reflective of his key players’ unyielding plight. Tokyo Twilight takes cues from Hollywood noir with its lingering shadows and muddy, imperfect stages to create a universally unforgiving, ultimately aimless cinematic world that affects in its grim emotional parallels to our own society, rather than a disproportionate dystopia that would surely lost its lustre in time. An exceptional, sorely underscreened gem.

21. Eureka (2000)

The longest single film on this list, S’s Eureka stretches on for s- and I feel it would be unforgivable to divulge any one of its plot-lines. Even for the richest year in recent cinematic memory, Eureka still ranks amongst the very finest flicks of 2000- and indeed of the decade as a whole: A solemn, visually striking and uniquely… Japanese portrait of grief. Only in such a country could such sobriety and affecting melancholia be paired with a tactile stream of humor, levity and unwittingly welcome absurdism- all woven into a heaving tapestry of human emotion that quite simply has to be seen. Don’t read any synopses- Don’t look into it- Just see Eureka.

20. Vengeance is Mine (1979)

Director Shohei Imamura is a superlative figure of indecent cinema. His dark, damaged characters and confrontationally charged situations articulate a shameless fascination with the corruptibility of the human soul. Vengeance is Mine transposes Ryūzūo Saki’s account of real-life serial killer Akira Nishiguchi with harrowing sophistication: Presenting a deeply violent, sociopath and yet unmistakably real human being with all of our idiosyncrasies netting his nest of amoral destruction. Imamura’s pacing does clash with the flow, as per, but I find that in this case the story warrants an extended runtime and in the end delivers a uniquely metaphysical resolution to such a brutal piece of work- calling on the wind and the earth itself to cast their last judgement.

19. Yojimbo (1961)

In the realms of action cinema, little snaps at our heels quite like Yojimbo. Kurosawa’s endearing use of leitmotif stings a spring into the step of his characters and works as well at tentpoling tension as well as any Morricone score. The sharp action sequences are somewhat blunted by the slappy sound design and appreciation of public squeam- something flicks like The Sword of Doom and Assassination have no trouble with- but what it gives in exchange is a constantly comedic take on the base of Red Harvest- Mifune turning out a classic performance that oozes with physical personality and wit, working as the keystone to what is arguably the finest straight-up action film ever made.

18. Audition (1999)

Audition is a film with feverishly precise control of its own tone. The otherwise hit-and-miss Takashi Miike has made his name off the back of a prolific, occasionally fruitful career that has given life to seminal classics like Visitor Q and Gozu– but little about his directorial style outwardly conveys the confidence and acute skill required to pull off something as audaciously twisted as Audition. Far more mature than any of his surrounding work, Miike’s opus explores a simple premise with brutal efficiently: Tainting each tender moment with a lusciously grim palette and eerie pacing that sets every scene on a razor’s edge of something going horrifically wrong. Audition represents a mesmerizing peak of that endlessly admirable Japanese comfort with genre film-making: Unraveling its crystal clear enigma to transcendentally shocking effect. To see is to believe.

17. Ran (1985)

Kurosawa’s most famed Shakespeare adaptation- if one that in my mind surrenders too much ground to its inspiration. King Lear is an impeccable piece of writing- but on the screen it lags to a sluggish grind that fails to recapture the stunning sensation that is the first 85 minutes. From beginning to the unfathomably profound siege sequence- Ran is a masterpiece: A slice of cinematic artistry unparalleled within Kurosawa’s more than impressive oeuvre- and a doubtless shoe-in for the Top 10. But after this masterfully handled build-up and payoff Kurosawa continues the tale of King Lear in a way that seeps along tediously- listless and flat despite the efforts of perfectly played villain Lady Kaede. It’s a genuine shame that Ran squanders so much potential, in my mind anyway, on faithfulness- but at the very least the incandescent flame of the first half burns bright enough to secure its place in the top 20.

16. Princess Mononoke (1997)

Hayo Miyazaki’s dark fantasy allure has never been particularly complex. Any movie with a message usually fails to communicate it in a sophisticated way and as Orson Welles so aptly put it: “It could be written on the head of a pin”. The blunt and blatant message of Princess Mononoke, however, rings a little truer in the heart than it does in the mind. Miyazaki’s carefully constructed divide between men and monsters drives fascinating comparison with how the ancients saw our world- and how the inevitable collapse of their civilisations might one day mirror our own. The mystique and mysticism of its characters is the core that allows Mononoke to transcend traditionally vapid message movie pitfalls- to slip its omnipresent through-line in without a word, every action gifting it gravitas and in doing so reinforcing the cinematic impact of what is on screen. The mutualistic relationship on display here speaks of Hayo Miyazaki’s profound talent as a film-maker- and that his work is more than dazzling creativity run riot.

15. An Autumn Afternoon (1962)

I think, for me to comment on An Autumn Afternoon, would be to waste breath I’ve already spent examining the movie Ozu made over a decade prior that he effectively remade here to be his final film. An Autumn Afternoon is just as elegiac, subtle and melancholy- managing to evolve several concepts put forth in the first film and expand upon them. It drifts away from some elements of the original to focus on other ideas- allowing a rare opportunity for a great artist to plug similar depths in the same mould. Ozu would spend his entire career making very similar films, yet managing to mine new areas of human interaction each time- producing some of the greatest movies ever made. Leaving such a venerable legacy in his wake, the man could have ended his run any way he wanted. An Autumn Afternoon is the perfect close to his shimmering oeuvre.

14. Throne of Blood (1957)

A masterful adaptation if there ever was one, Throne of Blood takes Shakespeare’s unparalleled Macbeth and forges an artistic text that stands on its own. Toshiro Mifune’s controlled, devastatingly human descent into murderous insanity remains one of the man’s finest roles- and Kurosawa himself bookmarks his film with exceptional images that are almost out of place with a director disassociated with centralised iconoclastic practice. Yet it is the imagery of Throne of Blood that makes it so massive. So engrossing and supernatural. The climactic attack sees one of the finest character conclusions ever put to film and cements it as a work of art that somehow sidesteps the imposing shadow of its parent play entirely.

13. Tokyo Story (1953)

Speaking of landmarks from the 1950s, there are few films that so indomitably run your aspirations as a filmmaker as Tokyo Story. A shimmering peak of Yasujirō Ozu’s impeccable filmography, always at his best, it’s a movie that exercises disarmingly simple cinematic language to achieve piercing, intimate effects. The audience are sat down with the characters- quiet voyeurs to a family slowly shutting the gradually degrading older generation out of their lives. Ozu allows all his characters a voice, composes elegant and impactful moments of revelation and only moves his camera once for a full 136 minutes. There is no objective “greatest” or even “great” film, but to those of you who choose what to watch based on such sites, I have to add that Tokyo Story is THE highest rated piece of work on Rotten Tomatoes, with an unbelievable 9.7 score average. Sufficed to say it’s patient, reflexive look at life and age has touched many immeasurably- and warrants anyone reading this list to give it a go for themselves.

12. Fires on the Plain (1959)

From Kon Ichikawa, arguably the most compellingly humanistic figure of postwar Japanese cinema, Fires on the Plain tells a tale of one man lost amidst a losing battle in the heat of WWII. It’s a film brave in its loneliness- depicting wartime situations in a vacant landscape absent of life and teeming with the emptiness of dread, each corner bearing another Odyssean figure set to either accompany or destroy our weathered hero. And, as with Homer’s epic poem, Ichikawa’s grasp over the bigger picture creates a densely emotional world, in which our hero is a puzzle piece being moved and motivated by generals far from the front lines. It’s a movie reeking in its own isolation, missing home and driven to amoral acts by the terror of survival. Masterful work by a quaint but nonetheless vital figure of the industry in the 1950s.

11. Samurai Rebellion (1967)

A key strength of Masakai Kobayashi’s drama is that he allows it to simmer, almost to a fault. His meticulous compositions and impeccably timed actions circle tighter and tighter around the central conflict- squeezing dry every inch of breathing room until all that’s left is the necessity to act- an underlying asset to his characters’ ever-present ideals of morality. In Samurai Rebellion, the act itself is at hand even upon reading the title but the man plays on it for every second- prickling audiences with tiny twinges towards the first sword being drawn before finally resolving in a bitter, brutal and ultimately bloody affair that continues with the remorseless rigour Kobayashi carries off so well: An incomparable ability to both construct the terminal inevitability of his characters’ situation as well as empathise with them every step of the way. It is in Samurai Rebellion that this selective humanism reaches its most evocative heights- and marries to the career culmination of one of Japan’s Greatest artists.

10. Eros + Massacre (1969)