Time for some trivia sessions. How many times have you watched a movie wherein a certain person, object or a set of motives has been hailed as something incredibly important, as if the only thing that mattered in the film was the object under discussion, only to find out by the end that it was alluding to something completely different? I bet, a number of times. Take a simple example from a basic narrative structure: a hero and a villain after the same thing in the movie only mentioned to be incredibly important, but no concrete explanation is offered as to why it is so. Numerous chases, confrontations and run-ins until one of the following is finally revealed:

a) The object was made up or doesn’t exist in the first place and was used as a motive driver for something else. b) It exists, but is far less consequential than made out to be in the film, and points to something larger/ more significant in the third act, or earlier in rare cases. c) It is significant as well, but alludes to a more intangible set of connections/emotions that are integral to the essence of the film. d) It exists, is significant in tangible forms as well, but by the end finds itself naught in the hands of either pursuant, thereby diminishing its physical value.

There could be other innumerable outcomes of the scenarios, but the core of the idea remains the same. What you’ve witnessed in all these cases, and more, is not a trivial movie twist. In film terminology, it’s a very common technique writers and storytellers often employ (and have been employing for decades now), called the MacGuffin. To sum it up, the MacGuffin in films is a plot device, something that is told to be of immense importance, but in reality is just used to drive the plot forward.

History and Usage

Plot device or not, come to think of it, MacGuffins have been an important, albeit unsaid or barely mentioned part of even daily conversations and exchanges. Infact, many theoreticians would argue that the first ever MacGuffin, even before it was called that, would be ‘The Holy Grail’. That’s right. Borrowed as a literary object from Arthurian literature, literally, according to biblical sources, it would be the chalice Lord Jesus drank from during The Last Supper. Figuratively, it is a plot device used to denote something elusive that the protagonists were after (akin to its modern definition) and is of great significance.

A treasure, or a map to a treasure is also among the oldest used examples of a MacGuffin for plot progression. Here, the treasure becomes the prime motivator, often for both the protagonist and antagonist, and the film/story may end in one of the four outcomes discussed in the introduction.

It was the famous auteur then, Alfred Hitchcock, who popularised the term ‘MacGuffin’ through its usage, and employment as a plot device in a number of films, starting with ‘The 39 Steps’ (1935), to be followed in his most famous works including ‘Psycho’ and ‘North by Northwest’. The term, though popularised by Hitchcock, may have been coined by his friend and screenwriter Angus MacPhail, but that is a discussion for another day.

As the years passed, and films changed form, appearance and structure, the definition of the term ‘MacGuffin’ has seen a lot of deliberation too. While filmmakers continue to argue as to what the ‘true’ nature of the MacGuffin is, regarding its usage, interpretation and who it motivates or affects most (including the audience), the core, as said earlier, remains essentially the same: it is indispensable in taking the plot forward, wherever employed, consciously or unconsciously. In that nerve, it would be informative to delve into what three accomplished personalities in the field of film have to say about it. Read on.

Alfred Hitchcock’s ‘Lion Trapping Apparatus’

In a series of lectures and interviews, Hitchcock has fondly narrated this story that indicates what the MacGuffin meant to him. “It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men in a train. One man says, ‘What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?’ And the other answers, ‘Oh that’s a McGuffin.’ The first one asks ‘What’s a McGuffin?’ ‘Well’ the other man says, ‘It’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.’ The first man says, ‘But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands,’ and the other one answers ‘Well, then that’s no McGuffin!’ So you see, a McGuffin is nothing at all. In crook stories it is always the necklace and in spy stories it is always the papers.”

In other words, he completes: “It (MacGuffin) is the thing that the characters on the screen worry about but the audience don’t care.” This here is a very important differentiator for the modern usage of the term from the Hitchcockian one.

George Lucas’ ‘Driving Force’

In a more modern sense, and very much in contrast with the Hitchcockian school of thought, George Lucas described the MacGuffin as such. “MacGuffin is still an object/prop that acts as a plot device, but it’s just as important to the audience as it is to the characters. Things like the ring in The Lord of the Rings, the horcruxes in the Harry Potter series, and the Ark of the Covenant in Raiders of the Lost Ark are great examples of the modern MacGuffin.” Lucas said this in an interview explaining the search for R2-D2 in ‘A New Hope’, as his interpretation of the modern MacGuffin as something that was essential to, and “the driving force” for the plot, something the audience cared about deeply for the sake of involvement, as much as the protagonists and antagonists did on-screen.

Yves Lavandier’s ‘M.O. of the Villain’

Lavandier’s interpretation is much more along the lines of Hitchcock’s, but differs in it affecting and motivating the villain more than the hero. The protagonist, in the strictly narrative sense, is just someone who gets caught up in the pursuit and wants an out. “In a broader sense, a MacGuffin denotes any justification for the external conflictual premises of a work”, he says. While it is a fresh school of thought and completely ripe for discussion, I feel that it encompasses lesser movies in its purview than the other interpretations, ones I would like to term the ‘Classical’ and ‘Modern’ definitions. It then lands up somewhere in between Hitchcock’s and Lucas’ interpretations, and finds merit in a select few films like Hitchcock’s own ’39 Steps’.

Popular MacGuffins

Having made a significant effort in understanding what a movie MacGuffin actually means, the discussion would be incomplete if we don’t delve into the most popular/significant examples of MacGuffins in films we have seen. Some of them are classical examples (Hitchcockian) and the others are more akin to the modern definition. What is constant is filmmakers’ and storywriters’ obsession with them, especially those in the thriller and adventure genre.

1. Citizen Kane (1941)

That one of the greatest films ever made would incite dialogues and discussions over its plot years hence should come as no surprise. The MacGuffin in this one is quite tricky though. ‘Rosebud’, the singular word around which the entire film is strewn about, the famous last word uttered by Charles Kane, is in many ways a MacGuffin, and in many other ways, not. In those, it becomes more of something that actually holds and imparts meaning (contrary to a MacGuffin that actually loses meaning as the film approaches its end). The sled on which 8 year old Kane played on his last day in Colorado is symbolic of his lost childhood and innocence, something he traded for a successful life in the publishing business. For Jerry Thompson, finding the meaning of ‘Rosebud’ becomes the primary presence guiding him through what he does in the film, though elusive as ever. In the end, he dismisses Kane’s last word as an unsolvable mystery, later to be revealed to the audience and meeting an inopportune end in a furnace.

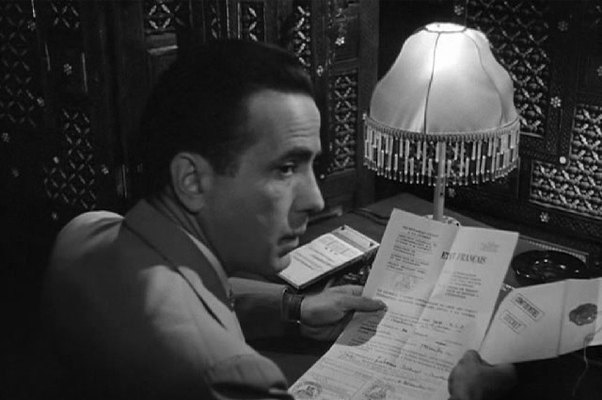

2. Casablanca (1942)

The quintessential classic American film. The story is squarely about the two lovers set against the backdrop of the early stages of the Second World War, and the tough decision faced by Bogart’s character, of hanging on or letting go, when an old flame shows up at the doorstep of his nightclub in Casablanca. The famed ‘Letters of Transit’ prop is the MacGuffin here, in the sense that it motivates majority of the actions happening in the club that night, but it essentially serves as a backdrop, therefore diminishing in its own importance and fostering something almost completely different from what it’s supposed to accomplish.

3. North by Northwest (1959)

Mentioning popular uses of the MacGuffin and not discussing the master’s works would be a blasphemy to his name. The interesting thing to note here before we begin, and to derive from the definitions is that Hitchcock never intended the MacGuffin to be more than a gimmick, a false trail of sorts to be pursued only in vain in his movies. How his movies end up supremely entertaining masterpieces despite the primary motive of the pursuants being something shallow or non-existent is a matter of his craft. The MacGuffins in North by Northwest are dual in nature and just as equally inconsequential. The first, George Kaplan, a fictional man Thornhill (the protagonist) is after to prove his own innocence; and the second, the microfilm in the Mexican sculpture, never really shown on screen, yet touted to be something of immense importance. What does the microfilm hold? Nuclear Secrets? Financial codes? The key to invincibility? We’ll never know.

4. Psycho (1960)

‘Psycho’ was the first Hitchcock film I saw back in the day, and I was completely enthralled by the multiple layers of corruptivity and the sheer complexity in plot the film exhibited. There are a lot of things the film is popular for, none perhaps more than the infamous shower scene and Norman Bates’ menacing smile towards the close of the film. What the film is also popular for among many film enthusiasts is its probable use of a double MacGuffin. In the same vein, here is some food for thought. In the strictly Hitchcockian sense, everyone quite knows that the $40,000 stolen by Marion Crane is the primary MacGuffin in the film, since it guides her character almost completely and is elusive in nature but keeps the proceedings going for about forty minutes into the film. By killing off Leigh’s character, seemingly the protagonist with Perkins, somewhere along a third of the film’s runtime, didn’t Hitchcock introduce another MacGuffin, one that the audience knew won’t obviously be found/attained, yet keeps the pursuit interesting enough until Bates’ chilling revelation?

5. Pulp Fiction (1994)

The MacGuffin in ‘Pulp Fiction’ finds itself somewhere more aligned to the classical definition, yet again sticking true to the core of what a MacGuffin is. The briefcase Jules and Vincent are sent to retrieve for Marcellus Wallace at the beginning of the film is an able MacGuffin, one that is juggled in different hands and progresses the already eccentric and non-linear plot ahead. As is completely true for the nature of the MacGuffin, the true contents of the briefcase are never revealed. What the audience sees is a rather faint golden glow. While it piques curiosity, come to think of it, the briefcase doesn’t really matter when the credits roll, and that if you ask me is what the MacGuffin is meant to signify in the first place.

6. Titanic (1997)

Many of you may have pointed this one out, or at least felt the insignificance of it as a plot propeller. The Heart of the Ocean necklace in ‘Titanic’ is indeed a MacGuffin that establishes its significance in the beginning of the film as the search party salvages the wreckage of the ill-fated ship to find it. As an aged Rose Dewitt begins sharing her journey with the others, the plot focus shifts entirely on her romance with Jack and the sinking of the ship, as the necklace itself diminishes in value, until finally revealed to be with Rose the whole time who drops it in the ocean before the film ends.

7. The Big Lebowski (1998)

Easily one of the most outrageously funny movies I have ever seen, this one has a rather hilarious, albeit ridiculous MacGuffin that is employed by the Coen Brothers to mine well-earned laughs. You guessed it right: it’s the Rug, because it really tied the room together, ya know?

8. The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003)

One Ring to rule them all. The One Ring is another significant example of a modern MacGuffin as a device used for plot progression that is equally important and is pursued with the same fervour by both the protagonists (the Fellowship), and the antagonist (Sauron) and his forces. The Ring, though in the films renders the bearer invisible for a short time, is said to be capable of far more powerful feats that are neither described nor shown. The Ring was forged by Sauron as part of his plan for dominion over Middle Earth in the fires of Mount Doom, and is later destroyed in the same fires by Frodo at the end of the trilogy, despite being the prime motivator, directly or indirectly, for all the happenings in the films.

9. Mission Impossible III (2006)

Perhaps the only MacGuffin on the list that satisfies all criteria laid and is as readily acceptable. In explaining this section though, I will let this piece of dialogue from the film do the work, mouthed by Benji in a conversation he has with Ethan before flying off to Vatican City.

“I’m assuming it is a kind of code-word for a deadly weapon, something Davian is going to sell to his unspecified buyer for 850 million, by the way. Or maybe it’s not a code-name, maybe it is just a really, really expensive bunny appendage. Whenever I see, like, a rogue organization willing to spend this amount of money on a mystery tech, I always assume…it’s the Anti-God. End-of-the-world kinda stuff, you know. But no, I don’t have any idea what it is. I was just speculating.”

There, you have it. In the classic hero-villain scenario explained earlier in the article, the MacGuffin here (the rabbit’s foot) is something the villain wants badly for his nefarious plans to take shape, and the hero, though unaware of what it can actually do won’t stop at anything to keep it from the villain’s hand, knowing probably just the nefariousness of the plan. The audience on the other hand, are just there for the fights and explosions!

10. The Harry Potter Series (2001-2011)

If you consider the entirety of the eight films composing the series, the MacGuffin doesn’t occur or even make its existence known until the close of the sixth film, ‘The Half-Blood Prince’, eventhough it did guide a motive or two in the first five films. The Horcruxes are what I call essential MacGuffins, very much in line with Lucas’ definition and essential in every sense, even crucial to the progression of the plot, so much so that the last two films in the series are almost entirely focused on Harry hunting down the Horcruxes with Ron and Hermione. Yet still, what the Harry Potter books, films and fandom solemnly stand for is not them. Infact, it is quite the opposite.

…..

There could be another hundred examples of films that employ the MacGuffin as an effective narrative device, several Indian films too among them. While the true meaning of a MacGuffin, I believe, will always remain under question and thereby form ripe ground for discussion, the prevailing dichotomy dictates that in a film, it is everything, yet nothing. Matter of perspective, you say?

Read More: How Are Sex Scenes Filmed, Explained

You must be logged in to post a comment.