Several years ago while lecturing a large group of film students on the cinema of the fifties, the subject of Marlon Brando came up. One of the young men put their had up and asked if he was the actor in The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996), asking directly if he was the fat one who had behaved so terribly on set. Bowing my head, I admitted that yes indeed, that was Marlon Brando. It occurred to me that an entire generation had no clue of the impact Brando had had on acting in the fifties, that they knew him only as the grossly overweight trouble maker on film sets in his later years.What a shame, when DVD and Blu Ray offer youth the chance to see him when he was the greatest actor in cinema, I mean no one was even close, and he changed it all for everyone. You can actually see the changes that took place in acting after 1951 in the work of established stars such as John Wayne, Kirk Douglas and Burt Lancaster, there was more of a an effort to be real, to find the truth in their work. They might not have been as method as Brando, but the search for truth in the role became paramount.

What a curse it must have been for Brando to be the greatest of his time and yet grow so bored with acting so fast when he was no longer challenged. He brought naturalistic acting to the theater and then the cinema, and even in his worst work he is fascinating to watch because he is so present in the moment…he is just there. Thank God, film is forever. Thank God, generations to come can go back and look at the extraordinary work of this immensely gifted man so many called a genius.

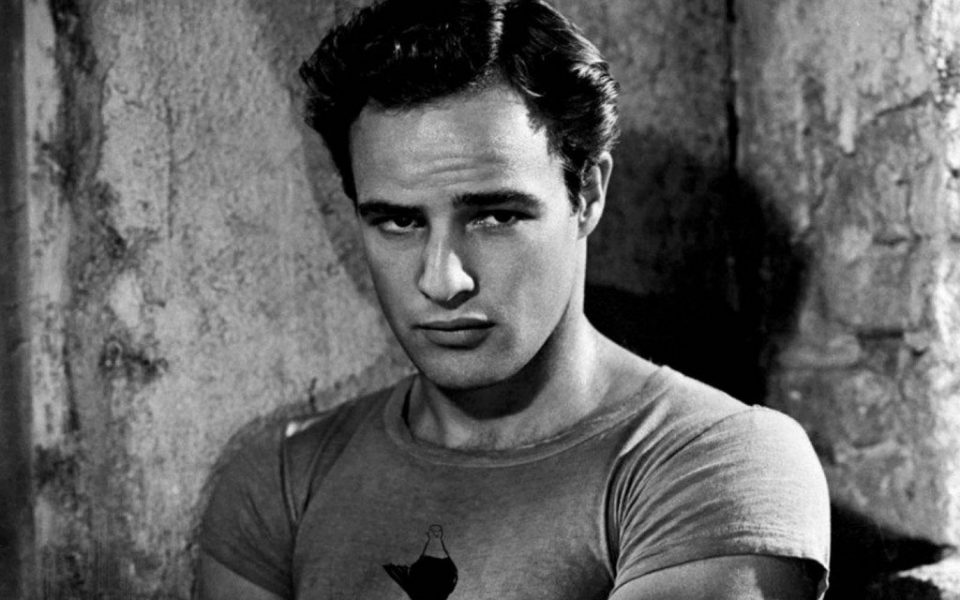

Blessed with stunning good looks and a perfect physique as a young man, Brando exploded into film with his searing performance as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), a role he had made famous on stage. Under the direction of Elia Kazan, who knew how to work with the young actor he gave one of the most searing performances in the history of the cinema, forever changing the art of acting with his startling realism. Brando did not merely act the role, he became the part, allowing the role to seep into his pores, so that he stalked the screen like a young lion. Critics were stunned, blown away by the realism of the performance, they had simply never seen anything like him before.

A year later, again under the guidance of Kazan he gave another superb performance as Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata in Viva Zapata! (1952) earning his second consecutive Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. Stung by the critics who griped that he mumbled, that the performances were alike (rubbish) he accepted an offer from John Houseman to portray Marc Anthony in a film version of Julius Caesar (1953), in which he would be surrounded by British actors who had grown up on the work of Shakespeare. Brando responded with one of his finest performances, speaking the words of the Bard in precise perfect diction exploding with the simmering rage of the character. Houseman was astounded not by the talent, which he knew already was there, but by the commitment; Brando gave himself over to the role in every way possible. Standing over the slain Caesar, he roars to the gathering crowd and pulls them over to his side, very gently, with absolute force. He dominates the film, and for his efforts received a third straight Oscar nomination for Best Actor.

With On the Waterfront (1954) he not only won the Academy Award, he gave one of the greatest performances ever put on film and one of the most iconic performances of his time. As Terry Malloy, the punchy ex-boxer, betrayed by his brother, now being used as a pawn in a murder, he was electrifying. We can see the slow dawn and realization of what has happened to his life come over him in the famous taxi cab scene with Rod Steiger as his brother Charlie. In the tender moments we see with Eva Marie Saint, we see a boxer tormented by his actions, his past, trying to be a decent man, trying to be a good person, because for the first time in his life he is in love with someone who loves him back. There was something dreamy about the manner in which he played the part, struggling for the next thought, knowing right from wrong, at war with the fact his own brother betrayed him and the men he thought were friends were anything but.

On the Waterfront (1954) is among the greatest of American films, and anchoring the film is Brando with a stunning performance of such purity and beauty it must be seen to behold.The film became one of the biggest hits of the year and was nominated for a slew of Academy Awards, winning eight in all, including Best Picture, Best Director and of course, Brando’s first Oscar.

It would be eighteen years before he again won an Oscar, and the years in between were bleak as he fell out of favor with the studios, became virtually unemployable as he was deemed increasingly more difficult to work with. He was responsible for directors being fired off films, drove others away and his terrible behaviour drove the budget of Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) far past its original budget. By the end of the sixties, he could not get a job and was considered a has been. Throughout that decade he was attacked by critics for his self indulgent work on screen, for his terrible attitude on most film sets and for squandering his talent. He did direct one film, the western One Eyed Jacks (1961) taking over when he fired Stanley Kubrick, and making a solid, very different western that has since become a cult classic, and he worked with one of his idols, Charlie Chaplin though the experience was not good for either man. Hollywood had stopped taking him seriously as an actor.

However, many had not forgotten his early genius and kept their eye on him. Francis Ford Coppola wanted him for the lead in his film The Godfather (1972), to portray a seventy five year old gangster chief. The studio balked, claiming Brando was finished, but Coppola would not hear it, fought for Brando, managed to get a screen test which convinced Paramount he was right for the part. The result was one of the most iconic performances in movie history, a brilliant, haunting piece of acting in which he portrayed a mafia leader, a father, husband and grandfather, allowing us to see the humanity under the monster. For his work he won his second Academy Award, which he refused in an action that has become legend. When his name was announced, a woman dressed in full Native American garb walked to the stage and refused the Oscar for Brando because of the treatment of the Indian on film. It was sort of cowardly move on Brando’s part, he should have refused the award himself rather than subjecting this woman to such scorn and wrath.

His performance in The Godfather (1972) was fascinating, fearless, as he acted his first moments in the film with a cat in his lap. and his death scene with a child, both usually the bane of an actors existence. We wondered often throughout the film how could this seemingly gentle man be a minster, a man who plays with his grandchildren yet orders a horse head placed in the bed of an enemy, or orders the murder of his foes…it is an astounding performance and though on screen for just thirty minutes of the films three hour running time, he dominates the film, his presence in every frame.

A year later he gave the one of the best performances of his career in Last Tango in Paris (1973) as a widowed American adrift in Paris who enters into a purely sexual affair with a younger woman to escape the grief of losing his wife. Brando is paralyzing in this film, which was almost entirely improvised from an idea by the great director Bertolucci. Drawing on his own life, this might be the most pure of all his performances, the one closest to his soul and for it he won a slew of critics awards and should have won the Oscar, but there was no chance of that after refusing the Oscar for The Godfather (1972).

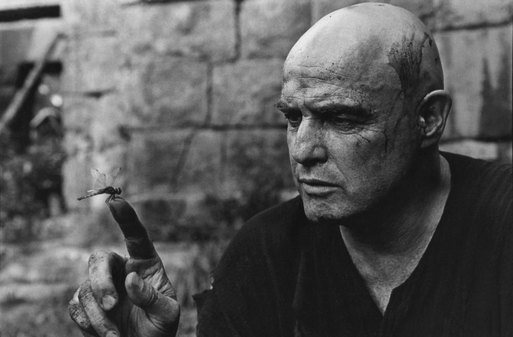

Suddenly red hot again he saw the chance to fill his pockets with movie deals and wasted no time in doing so, using the money for his island in Tahiti and for the Indians causes he was caught up in. Huge paydays for The Missouri Breaks (1976), Superman (1978), in which he is superb playing Jor-El as God the father, and The Formula (1980) kept him in the public eye but it was his searing work in Apocalypse Now (1979) that critics adored. Once again though the old Brando was showing up on set, causing issues with his erratic behaviour. Even though he admired Coppola as a director that did not stop him from showing up on set wildly over weight having not read the script and bursting with ideas about the character that slowed down filming when Coppola was over budget. Yet the Brando genius was also at play; he understood Kurtz, how to infuse the character with his own beliefs about the war, and captured perfectly the ache of brilliant man seen for being ordinary at long last. It was his last great film performance, though he worked consistently through 2001,and one for which he deserved an Oscar nomination.

Brando won an Emmy for a frightening cameo he did in Roots II – The Next Generations (1979) as American Nazi leader George Lincoln Rockwell, and for his single scene with James Earl Jones as Alex Haley he won Best Supporting Actor in a mini-series. His final Oscar nomination for The Dry White Season (1989) as a lawyer in South Africa, though the film was little seen and the nod felt like one of those sentimental nominations they throw out to elderly actors at the end of theirs careers. He was far more deserving for his comedic performance in Don Juan DeMarco (1994).

Brando changed everything about film acting around the globe, bringing to it a new realism that had simply not been there before. We were finally see ourselves on screen with all of flaws and foibles, and he was fearless in portraying that to us. Utterly fearless. And, while we watched breathless as he stunned us on screen, we also watched him grow bored with acting, fat with indulgence and finally detaching from society into his home on Mulholland Drive. In thirty years, I have not interviewed an actor who did not hold Brando in high esteem, who did not discuss his work with energy and eyes ablaze. He changed everything and paved the way for those who followed. And of course, he was surpassed — that is what is supposed to happen, is it not ?

He was at the end a fallen God, who through the years despite the genius, the absolute genius, had shown he was finally, all too human.

You must be logged in to post a comment.