French cinema’s pre-Nouvelle Vague directors often eclipse the creatively rampant artists who emerged during the 1960s, though a curious oddity who worked through both periods and beyond is Robert Bresson, a man famous for his express simplicity and nuanced command of eliciting human emotion. An undeniably attractive quality of his work is the short running times all of his movies come packaged with, few ever taking above 90 minutes and some even stooping below 70. With that in mind, if this post intrigues you remotely, I highly suggest checking out his work: It’s an imbalanced collection of botched projects mixed in with some utterly masterful creations that make for a fascinating career progression if you have the time to track through.

Impressionism

Robert Bresson’s cinema is like little you will ever see. Imitators fail to capture his everyday poetry primarily because the man’s impressionism so strongly characterizes the way his stories are told. To put it bluntly: Trying to make a Bresson film instantly fails to do so because his work is hugely personal, using characters and situations to insert his individual worldview. Nothing in his oeuvre so clearly exemplifies this personality as Lancelot du Lac, Bresson’s retelling of Arthurian legend and the quest for the Holy Grail.

Unlike contemporaries of the time, John Boorman and Terry Gilliam, with Excalibur and Monty Python, the Frenchman takes a far more restrained take on a piece that has been steeped in fantasy for centuries. Rather than knights in shining armor battling beasts, it pits soldiers against each other in brutal, bloody combat (a rare success for the violence-abhorring Bresson) and uses the setting as a shade through which to place men and women and observe the differences in Medieval society. Like Haneke, this look at life incorporates the existential issues the characters face- marking Lancelot du Lac as the most mature and effective story of King Arthur I’ve seen, despite itself.

Such an uncompromising vision allowed Bresson to share dramatic power with the simplest of stories; Mouchette’s tale of one girl living in a rural town is of particular note for its impressive minimalism mixed with a fiercely effective directorial technique that draws tension, dread and penetrating waves of shock out of the situation. Impressionism personalizes every screenplay the man takes on, slipping over a second sheet of observation for the audience to relate to, their experience with Bresson’s work colored not only by the story itself but the way the man views it.

Intimacy

Bresson makes frequent use of narration (a quality of Pickpocket that inspired Paul Schrader when he was writing the screenplay for Taxi Driver) and isolates the audience with a specific set of characters, forcing us to share both a physical and mental space. This technique does not automatically bear warmth; however, as such close proximity allows Bresson to highlight the flaws in his characters, meticulously studying their humanity through subtle revelations in their narration and relationship to the world around them.

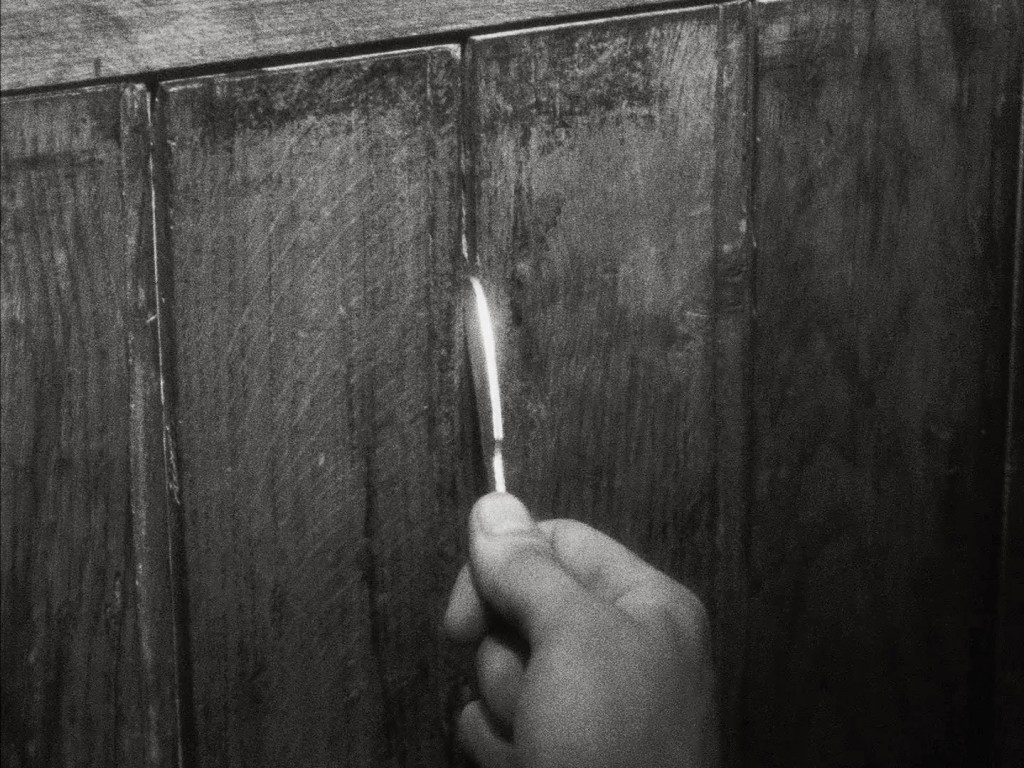

Most successful amidst these characters is Francois Letterrier, the eponymous Man Escaped in his 1956 masterpiece. Bresson cages us with the meek little guerrilla in a tight cell, our only windows to the outside seen through cast-iron bars and occasional wanderings in the yard and washrooms. The hugely intimate space we share with Letterrier is a keen insight into his worldview given real texture by his constant struggle to ply through the door of his cell. If the man was simply to sit and wait, Bresson’s philosophies would become opaque and heavy-handed- but with the vessel of such a well-developed individual, he is able to insert himself into the movie whilst also giving it a strongly defined protagonist.

Austerity

It would be wrong to ignore the faults of Bresson’s famously minimalist method, most damning in his terrible The Devil, Probably with its angry, rambling narrative devoid of any connection between characters or ability to compel the audience. It’s a loose expression of rage from Bresson himself which, in some scenes, works- but is ultimately fatal considering the simplicity of his style compared to incendiary masters like Gillo Pontecorvo who could have handled such a story far better. It’s important to note the man’s difficulty in portraying intense emotions and especially violence, certain scenes of physical attack coming across as laughably under Bresson’s inept hand.

So then, why is austerity also one of his chief strengths? Minimalism defines Bresson’s work in the cinematic consciousness- marking his separation from the ultra-modern artists of the Nouvelle Vague as well as the melodramatists of French cinema throughout the 40s and 50s. In au hasard Balthazar, it allowed the man to strip away the conventionally contrived plot elements which often abstract human reality and so acutely explore the cruelty and compassion of his characters. With jarring cuts through scenes, he efficiently slashes through his storylines without an ounce of fat to trim, combined with economical composition to cram as much into each scene as possible.

And it is due to this comfortably restrained direction that such dense cinema never becomes overwhelming. Instead, each scene is a richly layered depth that we are invited to dive into, rather than some byzantine construction overflowing with intricacies that swamps the audience. Stanley Kubrick’s work is infamous for losing its cinematic charm to overconsidered direction- and it is the technique of Robert Bresson that offers a fascinating alternative: Density done right that may lack the sweeping impact of Kubrick’s tsunami of information- but more than makes up for it with a uniquely intimate, tender and pure body of work.

Read More: Best French Movies of All Time

You must be logged in to post a comment.