Indian cinema overseas is more often than not equated with the great Satyajit Ray and his enviable array of works. While some might find it only befitting, it upsets the very concept of natural justice. Anyone remotely associated with the realm of cinema would know that the Indian reel world extends much beyond Ray and his creations. To start with, let us consider the curious case of Ray’s lesser known Bengali peer Ritwik Ghatak. A virtuoso by all means and rated as one of the most influential Indian auteurs ever, Ghatak wasn’t fortunate enough to receive the sort of universal acclaim that Ray received during his lifetime. Repeated box office failures, frequent political feuds with the power that be, a life full of worldly misdemeanours and a largely hated existence; Ghatak had taken it all in his kitty! But to his credit and fortunately for us, he still made some of the finest pieces in the history of global cinema.

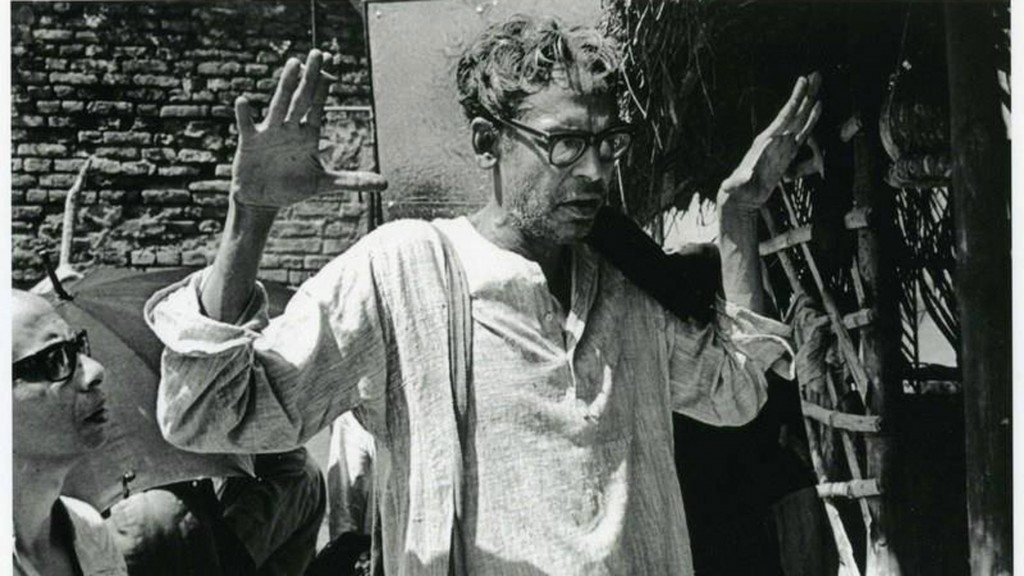

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to note that he was a true maverick, someone who never bothered to emulate anyone else’s style and someone whose style could never be emulated by anyone else. In fact, no one dared to walk down the same alley traversed by him for an obvious fear of sure-shot failure. It is rather interesting to note that Ghatak never considered cinema to be a source of entertainment. His opinion on cinema and entertainment becomes apparent when he writes in his essay ‘My Coming into Cinema’, “I do not believe in ‘entertainment’ as they say it or slogan mongering. Rather, I believe in thinking deeply of the universe, the world at large, the international situation, my country and finally my own people. I make films for them. I may be a failure. That is for the people to judge.”

An actor, writer, playwright, producer and director; the principal reason Ghatak forayed into the field of cinema is the medium’s widespread reach and universal acceptability. Also a teacher par excellence, Ghatak’s brief stint at ‘Film and Television Institute of India’ (FTII) in Pune shaped the careers of a number of future filmmakers who in turn tried to extend Ghatak’s vision through their own cinematic ventures. The list includes such stalwarts of Indian cinema as Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Saeed Akhtar Mirza, Kumar Shahani and Mani Kaul.

Born into a family of litterateurs in Dhaka (then in East Bengal, subsequently in East Pakistan and now the capital of Bangladesh), the Partition of India had a profound impact on his repertoire of works. The resultant cultural dismemberment of the Bengalis would go on to become the primary motif in most of his ventures. If we carefully look at the history of cinema, we would be able to appreciate that the founder of the Parallel Cinema movement wasn’t Ray, as is popularly believed. The actual initiator of the movement was Ghatak. The movement gained momentum with his movie ‘Nagarik’ (‘The Citizen’), an immaculately tragic portrayal of postcolonial India with partition acting as the subtext. Although the film was released in the year 1977, a year after Ghatak died, it was actually completed in 1952, a good three (3) years before Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali’ (‘Song of the Little Road’) was released. No wonder then that critics and film theorists often falsely identify ‘Pather Panchali’ to have pioneered the movement.

Ideologically an out and out communist, Ghatak was associated with the ‘Indian People’s Theatre Association’ (IPTA) during its initial days and played a significant role in reviving Bijon Bhattacharya’s legendary neorealist drama ‘Nabanna’, based on the 1943-Bengal Famine. Having made his debut through the unreleased ‘Nagarik’, Ghatak ventured into uncharted territories and made the highly experimental ‘Ajantrik’ (‘Pathetic Fallacy’ or ‘The Unmechanical’) (1958), a rather complex narrative on the emotional relationship between a driver and his car. A movie that expanded the Indian cinematic horizon significantly, it was released much before Walt Disney came out with its ‘Herbie’ series that also features a sentient vehicle. In fact, his next commercial release ‘Bari Theke Paliye’ (‘Running Away From Home’) (1958) had uncanny resemblances with François Truffaut’s ‘The 400 Blows’ (1959), that went on to become one of the standout pieces of the French New Wave. Both the films dealt with juvenile delinquency and societal neglect and had similar storylines. However, it needs to be noted here that ‘Bari Theke Paliye’ was released a year earlier!

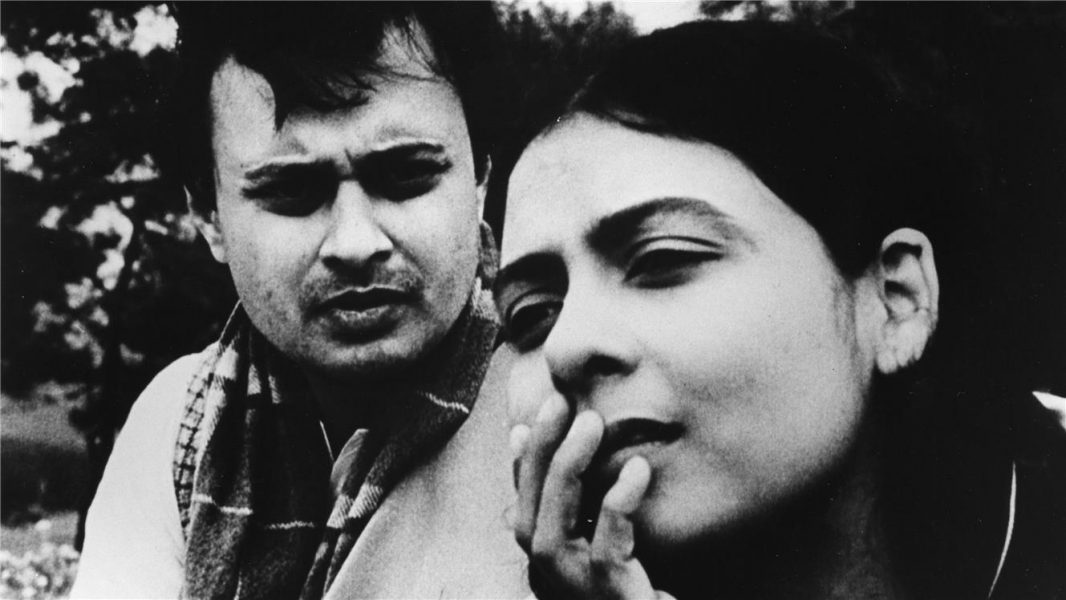

Ghatak’s next three films constituted a landmark development in Indian cinema in general and Bengali cinema in particular. ‘Meghe Dhaka Tara’ (‘The Cloud-Capped Star’) (1960), ‘Komal Gandhar’ (‘The Gandhar Sublime’ or ‘E-Flat’) (1961) and ‘Subarnarekha’ (‘The Golden Line’) (1962) documented the tragedy associated with the Partition of Bengal like nothing before. ‘Meghe Dhaka Tara’ went on to become one of the most celebrated Indian films ever made. In the 2002 Critics’ and Directors’ Poll executed by the Sight & Sound magazine, ‘Meghe Dhaka Tara’ was ranked at 231 and ‘Komal Gandhar’ at 346 in the list of greatest movies of all time.

The all-out commercial failures of Ghatak’s movies prevented him from taking up any new project during the later part of the 1960s thus turning him into a hopeless alcoholic and sending him into acute depression. However, he somewhat made a comeback and revived his career with the epical ‘Titas Ekti Nadir Naam’ (‘A River Named Titus’), released in the year 1973, when a Bangladeshi producer lent him helping hands. Ghatak made his last film ‘Jukti Takko Aar Gappo’ (‘Arguments and a Story’ or ‘Reason, Debate and a Tale’) in the year 1974. It was an autobiographical venture and featured the director himself in the role of the protagonist. However, the movie was released posthumously in 1977.

In between, Ghatak had worked on many other projects including documentaries, plays, short films and writing projects. Very few people are aware of the fact that Ghatak wrote the script for the Hindi reincarnation drama ‘Madhumati’ (1958), directed by fellow neorealist director Bimal Roy, for which he was nominated for the Filmfare Best Story Award. Additionally, he also worked as the scriptwriter for Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s debut venture ‘Musafir’ (1957).

As an auteur who always went against the establishments and broke all the prevalent conventions of cinema, it was nothing but an eternal struggle to artistically express himself. However, Ghatak did the undoable and consistently came out with intricately-woven yet immensely disturbing movies that continue to challenge our collective conscience and make us contemplate our respective roles in the society. Never to have bothered about the popularity index, Ghatak’s collection of unusual works is now beginning to attract the kind of international attention that it always deserved. It could now be safely said that the future generation would revere and appreciate Ghatak’s cinema much more than what his contemporaries did.

You must be logged in to post a comment.