Call it allegorical, call it enigmatic or call it deeply contemplative; when you delve into the dark and sinister world created by Andrei Tarkovsky’s ‘Stalker’ (1979), you can’t help getting enamoured by it! The film is nothing short of a journey into the dark alleys of uncertainty; one that is marked by hope, despair, narcissism, nihilism and above all a quest for what is ultimately humane. Let us all face it. The world demands a constant vindication of one’s existence. Tarkovsky, through this film, makes a subtle attempt at proving the futility of these vindications.

Although the film is set against the backdrop of an unspecified and dystopian future, the references and associations are fairly recognizable. Somewhat inspired by the novel ‘Roadside Picnic’ (1972) by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky; who eventually wrote the script of the film, it chronicles the story of a person referred to as the stalker who guides two other persons to a place known as the Zone. This place, which is otherwise dreaded for being fatal to visitors, is rumoured to possess the ability to fulfil the ‘innermost’ desire of any person.

What follows thereafter is a strong foray into the conscious and subconscious compartments of the human psyche. The journey into the Zone and its innermost sanctum known as the Room exposes the fears and insecurities of the three travelers. Simultaneous references to an earlier stalker known as the Porcupine constitute a recurrent motif pointing towards human greed and its obvious ramifications. One of the travelers is a writer who is making the trip in order to draw inspirations. During the course of his journey, he narrates his contempt for writing. He spits out his hatred for the readers who are only busy ‘gobbling’ up literary pieces without ever being aware of the pain and tribulations that go behind the creation of those pieces. The writer’s paranoia is an extreme manifestation of the eternal literary insecurity. The other traveler, who happens to be a physics professor and seems to be at peace for a significant part of the movie, involves himself in serious discourses with the writer debating the relative importance of science and arts.

Like all his other movies, Tarkovsky takes the help of significantly larger shots with some of them lasting for more than four minutes in order to establish his narrative. In the process, he succeeds in creating a sort of suspense that keeps people at the edge of their seats. With the help of apt and menacing cinematography by Alexander Knyazhinsky that concocts gloom and doom, the harmful effects of increasing industrialization are fittingly shown by the director. The urban-scape is set in the sepia tone while the Zone is set in colour thereby establishing the intent of the auteur. The place is symbolic of the universal human quest for hope, peace and order. Its sentient nature lets only those pass through its traps who it wants to pass. The film could very well be described as the ultimate confrontation with mayhem. The director, in his characteristic style, exposes the definitive human insecurities through this assay. The narrative is rather simple and linear and is even indicative of order. However, ingrained within its calm narrative, there is a constant effort at unraveling the innermost human desires. There is something deeply unsettling that permeates through the movie; something that compels us to think beyond what is obvious and apparent.

The music by Eduard Artemyev perfectly blends into the vague and unnerving ambience created through the striking set of visuals that would surely go down the annals of cinematic history as one of the best. It is representative of the multiple emotions that the film tries to portray – those of fear, happiness, trust, love and above all the essence of being human.

Read More: ‘Three Colors: Red’ and the Mysteries of God, Life and Valentine

The film could also be taken as a metaphorical statement against the increasing nuclearization that was witnessed during the seventies of the last century. In one way or the other, the movie makes an obvious rebuff at the over dependence on technology and the mindless voyage of science towards a point where humanity gets reduced to nothingness. Some of the dialogues between the three main characters exhibit a general disdain for intellect that doesn’t take human emotions into account. In fact, the final monologue given by the stalker’s wife embodies the perennial human enigma – that of the conflict between logic and life. As a matter of fact, the film is somehow reminiscent of Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘Alphaville’ (1965). The over-dependence on the rule of law and logic at times contributes to a general decay in human qualities.

While the general mood of the film is inclined towards somberness, the ending has intentionally been kept towards the brighter side and this duality probably drives the point home. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to note that the film is a subtle portrayal of life in itself.

The scripting is impeccable to say the least as the moral and ethical ambiguity of the principal characters is maintained throughout while making the audience empathize and sympathize with them. In fact, the vulnerability of the characters makes for the audience to emotionally connect with them. Tarkovsky, the fantastic storyteller that he is, makes an interesting case study of the contrast between brightness and darkness and shows that the difference is tinier than what we would otherwise like to believe.

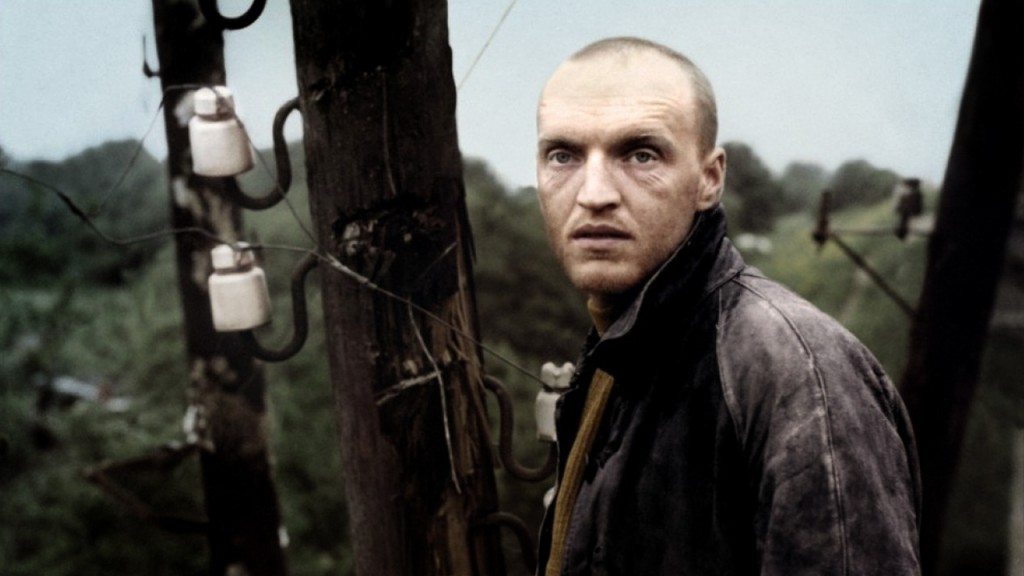

The acting is one of the high points of the movie. Anatoli Solonitsyn as the writer steals many hearts with his emotional outbursts as well as contemplative musings. Nikolai Grinko, playing the role of the professor, is at his fluent best, while Alexander Kaidanovsky as the Stalker is sublime.

The only probable flaw that some might scoff at is the inherent slowness in the movie’s visuals. While there might be debates on whether or not the movie was a tad longer than what was necessary, the director did so intentionally and without a shadow of doubt. At the end of the film, the general viewer gets dazed and confused, exactly what every movie should essentially accomplish. Not for nothing was ‘Stalker’ ranked 29 on the British Film Institute’s 50 Greatest Films of All Time poll.

You must be logged in to post a comment.