If adversity is the crucible of great art, then Greece is as good a place as any to bring us one of the cinema’s great masters. Its checkered past of wartime destruction and prevailing poverty during the 20th century serves as the backbone for Theo Angelopoulos’ unique cinematic vision and, perhaps most admirably, one of his most endearing traits is the sense of humor with which the man handles the tumultuous state of affairs plaguing motherland. His style is as sophisticated as it is unbelievably light and simple on-screen, which speaks of his uncanny understanding for the nuance achievable in the cinematic medium- and though this method buckles under the weight of internal politics in some of his potential great works, the cinema of Theo Angelopoulos remains compelling from his debut in 1970 right up to an untimely swansong with 2008’s the Dust of Time. Here’s why.

Worldbuilding

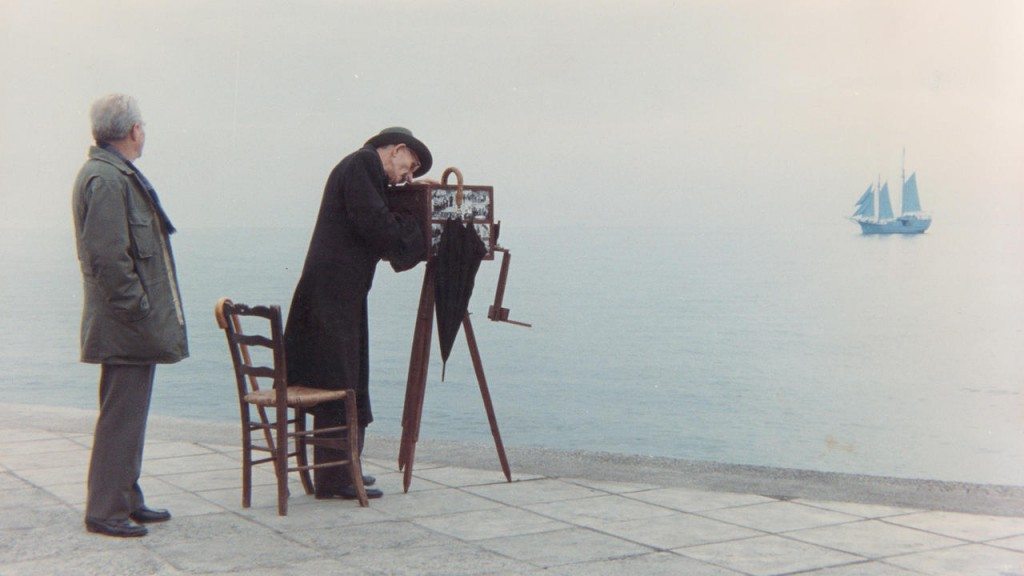

Angelopoulos allows his work to buckle and breathe. He actively engages with his audience’s attention and, through this understanding, sews a fascinating structure to his pieces that goes against every convention in the book. Instead of constantly pursuing important plot points to keep forward momentum at an intensive surge, Angelopoulos moves almost in a swell, flowing patiently and precisely placing vital moments so that they are followed with often many minutes of calm. He doesn’t wait idly and waste our time; however, he uses these moments to develop richly absorbing worlds characterized both visually by his long-time collaboration with cinematographers and through the people he populates them with.

In The Travelling Players, an early scene sees the eponymous group of performers settle down in a local café. The camera drifts towards the door to follow one of their runaway children, quickly caught outside as a troupe of soldiers enters the town square. They sing a marching tune, which quietly inspires political inspiration in several members of the group, who quarrel over their beliefs. It’s an impeccably directed sequence that, whilst not directly moving the people along, succinctly and cinematically establishes the divisions in the group that will take root with far more venom in said crucial sequences.

It is this preference for non-diegetic sound, exclusively featuring live music for his first four features and sparing use of unnatural noise for the next few, that makes his landscapes so vivid and full of life. They react culturally to the camera entering their space and always provide a conflict, be it political, social, or marked by the dilapidating cities of a poverty-stricken Greece. Angelopoulos movies are filled with adversity, strife, and woe fit to match works like 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days in their ominous depiction of a struggling Balkan nation- and yet somehow they are also gifted with a lightness and humor that allows them to glide off the screen…

Surrealism

Angelopoulos is perhaps cinema’s great unsung surrealist, contextualized with the subtlest offerings of Bunuel in That Obscure Object of Desire and the quiet absurdism of Lynch in the lighter parts of Blue Velvet. The staging and overall realization of his work lend themselves to a playfully constructed form of film-making, but it is the man’s ability to inject any moment with affecting doses of surrealism that defines this element of his method as so distinct and important to study.

Something as simple as a group of men wandering around in The Hunters can be lent an unsettling yet devilishly inviting air by the movement of Angelopoulos’ camera, drifting to inhuman heights despite the mundanity of his scene to slip a uniquely indefinable feeling into its midst. Something is off. Are they in danger? Is this a hint of some horrifying reversal yet to befall the party? The enthralling ambiguity of this style is what gives it its intrigue- but it is a direct comparison with Ancient Greek playwriting that invests Angelopoulos’ surrealism with its unmistakable bite.

For example, an early scene in Landscape in the Mist sees its two children fall upon a dying horse in the middle of the street, tortured by the bitter winds of winter and collapsing into the snow. The little boy stands sobbing whilst the older girl comforts it in its final moments- whilst a wedding reception bursts out of a nearby building and jubilantly makes its way down the street. The events are disconnected by space and time, distanced across an empty slab of snow and functioning independently of each other with beats in the action. This allows Angelopoulos to break up the feelings imparted by both and concoct them into an affecting juxtaposition of melancholy that is neither jovial nor depressing- centralizing our attention on the middle ground and, in doing so, commenting on the inherently puzzling way we live our lives happily in the face of its horrors and vice versa. It is the direct idea of artificiality and theatrics that lend them the magical quality of some kind of Grimm fairytale.

Microcosm

Angelopoulos’ humour and continental charm are key to his success, but the man’s profundity as an artist comes entirely from his ability to take disconnected scenes and make them seem like the most important things on the face of the earth. To move his audience beyond the traditions of storytelling and, without warning, deliver stunning microcosms that tell entirely separate and fascinating tales all on their own. Some of the best film-making involves scenes that can be taken totally independently of the film they are in and still stun the audience, and Angelopoulos has painted hundreds of such moments.

Take, for example, a scene in his debut: Reconstruction– in which a widow and her eloper, fresh from murdering her former husband, are shacked up in a hotel. The murderous man comes in to find his sleeping co-conspirator and, shrouded in darkness and observed by an angle that totally abstracts his face- he stands and watches her. Thinking. Waiting. Is the momentum of this lethal event going to spill over into his actions now? Is it carnal desire, lust and passion ignited by the closing Police presence on their position? Angelopoulos, through a static frame and simple blocking, is able to draw an exemplary moment of fear, indecision and burning humanity. This is one of many scenes that make his characters so lifelike and dense- allowing them not to function but instead thrive in situations presented with the intent to allow them to act organically. To show us who they really are- mentally or physically. His observation of the human condition is as profound as any other director to this day- and that alone cements Theo Angelopoulos as an underexposed name well worth of explosion into the wider cinematic world.

You must be logged in to post a comment.