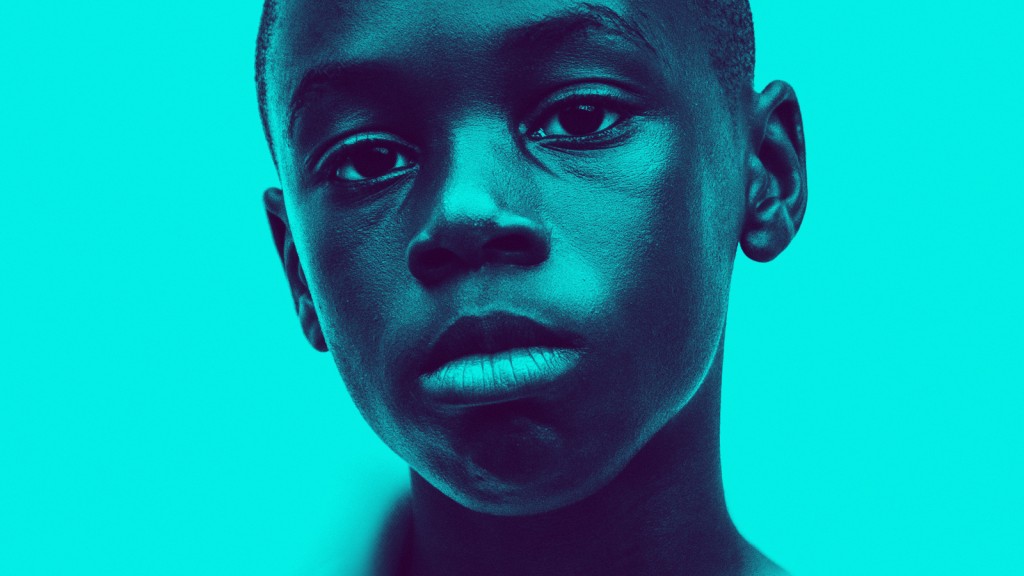

“In moonlight, black boys look blue.” When someone makes a list of the greatest movies of the 21st century, ‘Moonlight’ will be a guaranteed entry. Barry Jenkins’ expressive drama tells the story of Chiron, a young, sensitive African-American boy, who discovers his sexual orientation in an exhilarating odyssey. There aren’t many movies in the 21st century better than ‘Moonlight’ in terms of narrative structure and the marriage of sound and camera movements. The highly-praised flick also went on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture over the much favored ‘La La Land’.

‘Moonlight’ is spread over three distinct periods in Chiron’s life: early age, adolescence, and adulthood. Barry Jenkins, the writer-director of ‘Moonlight’, explores the subtle transformation and changes in behavior Chiron goes through in the backdrop of changing cultures and the allusion of society. By dividing his exuberant story into three fragments, Jenkins manages to narrate Chiron’s life in a way that is accessible for people.

Life is a growing process. One goes through numerable phases of changes throughout one’s life. You can’t be the same person in two different moments of your life. ‘Moonlight’ employs three different shades to Chiron’s personality to achieve this imperfection in our wholesome personalities. Jenkins paints Chiron’s character in presenting three complex stages of his life: fragility, mutability, and convolution. The three parts are marked by a distinct perspective on Chiron’s life, while still retaining the underlying internal crisis that binds him in the overtly chaotic world. Regressive emotions are expressed akin to the romanticized words of a poet, or a gentle, confident stroke of an artist. Jenkins uses body language and evocative camera movement to achieve a sense of exclusion and solitude in Chiron’s life. Chiron communicates with the viewer, not often through words, but using this intertextuality of body and mind. His introverted nature is mimicked to a certain extent by the narrative style of Jenkins, making expert use of immersive sound and breathtaking visuals.

Jenkin’s ‘Moonlight’ is similar in stature and spirit to Linklater’s ‘Boyhood’ which released some years prior. The transition from boyhood to adulthood, though presented in both the films, differs starkly in the way it takes shape. The perspectives of characters and their socio-cultural shadows are different, hence making one more character-driven than the other in terms of its storytelling. While ‘Boyhood’ greatly benefits from its champion cast and Linklater’s contemplative writing, ‘Moonlight’ derives its power from Jenkins’ understanding of the African-American community and his efficient recital of solitude, not to assert that the performances in ‘Moonlight’ are any less subliminal. The visual representation of human emotions is the highlight of ‘Moonlight’, enabling Jenkins to accomplish a technical coup, a rare achievement in modern-day filmmaking. This expert juxtaposition of the most basic elements of storytelling engulfs the viewer in a maelstrom of overbearing feelings that move us closer to Chiron’s own battle with the world.

Synopsis

The plot of the movie follows the life of Chiron, an introverted black kid who struggles with his place in life and society. The film is divided into three segments, each dealing with three different phases in Chiron’s life. Different actors bring to life the character of Chiron in each stage, grounding the fantasization as close to reality and humanly as possible.

i. Little

Little, the paltry designation Chiron is reduced to for his timid stature, habitually finds himself as a target for bullies. He often becomes a prop in other children’s idea of recreation and descends into isolation. In one of his daily routines, he is spotted by a drug dealer, Juan, who goes to inspect and comfort him. After taking him to his girlfriend, Juan is able to get Chiron to reveal his neighborhood, in the process forming a bond of friendship and trust with him. When they reach his house, Juan is surprised and taken aback to find that Chiron’s mother is one of his customers. He confronts her about her parenting style, leaning on her to change the ways of her life. Instead, Paula turns the tables on him and accuses him of facilitating the whole process and saying that Juan is the biggest disappointment in Chiron’s life. An upset Paula shouts out at an out-of-tune Chiron, who barely registers the whole episode.

The next day, Chiron goes to visit Juan and asks him about the meaning of ‘faggot’, which he is often called by his peers. Juan assuages his fears and tells him that it is the word “people use to hurt gay people”. In a heart-wrenching scene, just after they connect beyond the frivolities of social obligation, Chiron unsuspectingly asks whether Juan is the one who provides his mother with drugs. Juan hangs his head in shame as a heartbroken Chiron leaves in tears.

ii. Chiron

This is probably the most powerfully-charged and rawest segment of Chiron’s life, like it is for any other individual on earth. Adolescence is the phase which really shapes our identities and makes us who we are. It is almost like the foundation for the edifice of life. As he was a child, Chiron remains introverted, sparsely interacting with the world around him with a sovereign intent. Bullies now become an everyday part of Chiron’s life, often compelling him to participate in their shenanigans. Tyrell, the band leader, often terrorizes him, indulging other boys in his acts.

Chiron’s relationship with Paula has further deteriorated, though Chiron deals with her more maturely. She has now started prostituting her body to support her addiction and often steals money from Chiron which Teresa loans him. He still visits Teresa, who’s been alone since Juan’s death. In a dream-like sequence, he imagines Kevin, one of his best friends, having intercourse with a friend in Teresa’s backyard. He proceeds to spend the night alone with Kev, discussing his worst fears and ambitions. The two realize the affection they harbor toward each other and engage in a passionate kiss, followed by another act of passion. At school the next day, Tyrell forces Kevin to punch Chiron, in an attempt to haze him. Kev reluctantly proceeds to do so, beating him back and blue until he faints. After not divulging the names of the boys who attacked him, Chiron viciously attacks Tyrell in the classroom the next day, and intently stares at Kevin as he is escorted out by police.

iii. Black

Adulthood treats Chiron as indifferently as the other stages in his life. He deals drugs in Atlanta, almost mimicking Juan from the start of the movie. Paula, his mother, is in frequent contact with him from the rehabilitation center she’s now in. Despite being sparse in contact with his mother, he goes on to visit her and admits his remorse at the lack of empathy he has for her. The two share an emotional moment, probably the only real speck of feeling they’ve had for each other over the years and apart. Chiron receives a phone call from Kevin, his old schoolmate, who invites him to a diner he works at. The sudden call out of the blue shocks Chiron, who proceeds to meet him.

The reunion goes well for the most part; Kevin reveals he is a father to a child he had with his ex-girlfriend, and despite not being what he wanted to be, he’s content in life. Chiron’s silence, when probed by Kevin about his life, is filled out by the song that reminded Kevin of him. Chiron finally opens up and confesses to Kevin that he hasn’t been intimate with any other person other than him after the night at the beach. The two embrace and the camera pans to a young Chiron, in the moonlight, blue as a clear sky, on the beach, gazing at us.

Moonlight and the Breeze

The two most prominent cathartic motifs that Jenkins uses in his film are the oceanic breeze and moonlight. The two elements often appear on the screen when Chiron is really comfortable with who he really is. The beach becomes almost like a safe haven for Chiron, a place where he is alone with his thoughts, a place that doesn’t discriminate and embraces his flaws and imperfections; a place where he is at peace. Right from his first experience with Juan, to his special night with Kevin, the breeze, that is evidently amplified to achieve the desired effects, is symbolic of the calmness and serenity that we all long for in life. It slows down proceedings, allowing for the viewer to breathe and cherish in the satisfaction of Chiron.

The moonlight is probably the most important symbol of Chiron’s loneliness and yearning to be his natural self. The film is inspired by Tarell McArney’s play, “In Moonlight, Black Boys look Blue”. There aren’t many instances in the movie when we actually see Chiron in the moonlight, barring, most notably, the last scene, but the essence of what it means looms like a shadow. Moonlight assumes importance in the story through Juan’s childhood story about an encounter with a woman who gave this famous quote.

The Struggle with Masculinity

One of the underlying tussles that Jenkins focuses on apart from the evident clash of cultures and periods of time, is Chiron’s tryst with the society and its expectations. In each stage of his life, Chiron goes through tremendous suffering at the hands of others around him. His incongruent sexual orientation sticks out like a sore thumb, often drawing raised eyebrows and unpleasant remarks. He is trapped by the society’s expectations of masculinity, something which continues even when he feels “cool and slick” like Juan. Jenkins visually translates this skirmish with emotionally charged body movements and expressions, laced with subtle self-consciousness and an explosive energy.

His inner-self is perennially at odds with the chaotic environment around him and his yearning for peace and self-expression. Chiron is expected to become a “man”. This fixation on typical gender roles and stereotypes is something that homosexuals suffer across the globe. Chiron’s community presses on him to change the way he really is and conform himself as the person the society wants to see him as.

Using the character of Chiron, Jenkins endeavors to present a universal roadmap for men all around to overcome harsh surroundings and become a part of themselves first, before trying to become that of others. He urges boys like Little and men like Chiron to accept a part of themselves that seems so lost on them when viewed in the comparative socio-cultural context. His deeply afflicted protagonist, though, is someone who can’t come to terms with who he is because of how strongly imprinted upon him is the image of a masculine man. The standards that others set for him, including his own mother, making him a tempest of volatility.

Act three, ‘Black’, confirms our worst fears. Chiron puts on a charade of the person that he never wanted to be, but was forced to become. He’s reduced himself to a mere projection of how the society views him, as opposed to how he really wants to be. The hardened drug-dealer persona, the expensive car, the grimly poker face, are all features that he has appropriated from the community’s vision of the perfect man. Chiron has become a person that he thinks he needs to be. In fact, ironically enough, Chiron’s only real moments as ‘Black’ are when he comes up against two people he hates to love the most; Paula and Kevin. They make the gritty exterior melt into a sensitive, human core that is as helpless as the ‘little’ kid under the moonlight, alone at the beach. The nature of Chiron is drawn against his nurtured version, which becomes the eventual heartbreak and soul of the film.

Arthouse to the Hood

In an interview, director Barry Jenkins explained his unique built of the surroundings that the story is set in. Jenkins strays away from a socialist realist portrayal and instead adopts a different, more personable approach that reaps great benefits for the film. Jenkins disrupts the conventional cinematic formula for portraying a marginalized neighborhood and infuses in it a modernistic style that makes for an inherently riveting experience. One of his achievements is humanizing and transforming the stereotypical narrative-trajectory from the jarring depiction of misery and violence to a place of introspection and sophisticated, idyllic violins and cellos filtering the big-city sounds of Miami. The very use of this method comes as shock to us. With a fabricated reality that we didn’t expect to be an audience to, Jenkins creates a surrealist experience for the viewer that is as close to reality as possible.

Jenkins uses the tragic mismatch between Chiron’s inner reality and exterior life to reflect a mismatch of our expectations as a viewer. ‘Moonlight’ relinquishes the harshness of hip-hop and the brutality of guns and embraces the stunning language of classical music and haunting, poignant images.

Many critics have described the movie as a visual poem, akin to the stark cinema of Tarkovsky. Jenkins drowns the viewer in hazy, contemplative visuals, creating almost a hypnotic effect. Just like Tarkovksy, Jenkins draws us in with an exotic syncretism of highbrow symphonies and exhilarating images. This choice of presentation not only plays to the millions ghettoized in failed housing projects, but also includes members of the community who’ve made it big and actually live a lavish lifestyle.

Camera and Sound

The use of visuals and an actor’s ability to express his emotions through body language is a rare commodity today. More often than not, filmmakers try to overdo and end up making a mess. Jenkins, though, triumphs with flying colors in his use of camera and sound. Jenkins uses the camera to describe characters. Fluid camerawork establishes a deep connection between characters, while disruptive cuts point to a raw, undeveloped bond between characters. For example, when Chiron first meets Juan and Teresa, Jenkins uses continuous takes to pan the pair, but whenever any one of them interacts with Chiron, he mixes two separate scenes. The camerawork denotes how Chiron doesn’t trust the people he has just met and is apprehensive to exchange information.

Jenkins places the camera in between the characters and invites us to look inside-out, rather than the other way around. Chiron is so inert in his social space that even the camera can’t face him, often following him on his back. The expert use of the camera to capture emotions and make us experience what the characters feel is what draws ‘Moonlight’ from its contemporaries. Sounds, like the one where Little is chased by bullies, are used with an overwhelming magnitude to immerse the viewer in experiencing Chiron’s plight first-hand. The almost cathartic use of sound is extended with the beach and the breeze. We see the spectacle of great oceans wave crashing through our ears. This juxtaposition of sound and visuals is a new form of storytelling that is enhanced by the ingenuity and sincerity of ‘Moonlight’s sublime cast.

One of my favorite pair of sequences in the film is the circling camera used on two occasions. The first is in the first segment of the story when Little struggles to get along with other kids. The circular movement of the camera exudes energy and happiness of the kids. While in the second part, the circular camera returns, but with a different intention and purpose. Tyrell anchors the movement and immediately establishes a menacing energy. This contrast between two similar shots that are completely opposite in meaning goes on to prove Jenkins’ credibility as an artist. His use of a recurring motif that carries different meanings with it is unique and a testament to his craftsmanship. Jenkins repeats the same use of disjointedness in scenes where the sound of the actors doesn’t align with their lip movements, in an instance, no movement at all.

Initially, Jenkins experiments with Paula and concerts her crack addiction and high with her ability to spur words. The disjointed relationship between Chiron and his mother pulls his passive dreamer archetype, forcing him to be secluded from others. The second instance is when Kevin sees Black for the first time after a number of years. The relationship between the two obviously has gone through a period of change, especially after the school incident. Such brilliance in innovation sets new benchmarks for films and expands on the vast array of tools that directors have to facilitate their storytelling.

The Ending

The ending of ‘Moonlight’ is open-ended and provides for people to opine subjectively based on their experience of the film. The underlying themes that fuel Jenkins’ cathartic odyssey of self-discovery are the existential struggle between Chiron’s idea of who he is and the community’s imposition of their moral construct of Chiron. The dichotomy is innately unnatural and results in catastrophic consequences for Chiron. We see how he has molded himself in a bracket of masculinity that has been laid out for Chiron by others to fit in.

Black, as the third chapter is named, refers to how corroded the core of Chiron has become. The generous, shy, kind kid we saw in the starting of the journey, has petrified into an uncompassionate, hardened individual, putting on a facade to convince the world of his identity. Even though Kevin only appears very briefly in the first and the second chapter, his presence in the third is by far the most important and significant addition to the film’s thematic structure; the lover archetype.

In the beautifully layered personality of Chiron, Jenkins services two distinct archetypes that define his identity in each chapter. Little is the dreamer; isolated by the lack of empathy from his mother and peers; redeemed, briefly, by the companionship of Juana and Teresa. Black, on the other hand, is the deprived lover, yearning to relive that one magical night that is the only moment of meaning he has ever felt. The frustration that warped Chiron, being betrayed by the reciprocative efforts of Kevin, makes him a hollow individual, bereft of generating empathy for himself or others.

The downward spiral starts with him beating up Tyrell in the class and venting his anger at Kevin by indulging in violence. Chiron’s generosity gets lost on him and he loses his sense of identity after this incident, transforming into an almost unrecognizable man. It is striking how similar he is to Juan from the start of the movie. The superficial sense of reverence; the bossy, muscular demeanor, and the vile practice of selling drugs. The very nature of his personality has taken a different course that is diametrically opposite to his real nature.

Meeting Kevin, though, brings back some of his old self. His admission to Kevin about the lack of intimacy in his life apart from that night at the beach, reveals how distrusting and skeptical he had become of the institution of love after the betrayal at school. First Juan, and then Kevin fail Chiron’s innate goodness. This process not only changes Chiron’s outlook of others, but also of himself. The image superimposed on his character and natural state of existence becomes his reality, which he tries hard to conform to. From bossing around his employees to bullying them, Chiron comprehends life differently. But when he sees Kevin again in the diner, repressed memories and his original character return. He expresses his vulnerability to Kevin and his feelings for him, breaking down the harsh exterior and allowing him to see him as the old Chiron again. The two embrace, remnant to how intimate the two were that night on the beach.

But this intimacy is different. While the former was laced with raw passion, this meeting is marked by a noticeable change in maturity and acceptance of their individual identities. Kevin is now a father to his ex-girlfriend’s child and content in life. Even though he is bi-sexual, he is more aware of the person he really is. By the end, Chiron also returns to his old state. Kevin’s reintroduction in Chiron’s life has taken him back to the night at the beach and in a way returned him to the ‘little’ Chiron; innocent, curious, peaceful. Jenkins uses a shot of little bathed in moonlight on the beach as almost a metaphor to the acceptance of Chiron’s own individual identity and sexual orientation.

The now grown up ‘Black’ tries his best to relinquish his true self and dons a cloak of deception to fool people into believing him to be a person he isn’t, but they want him to be. His final gaze into the camera, assured and content, is like a beckoning for the viewer to enter into a world where he finally feels comfortable with who he really is. The beach, as mentioned before, is his safe haven, wherein every chapter he has experienced a life-changing moment. Chiron finds himself standing at the horizon of new things, a future where he doesn’t have to conform to standards levied on him by others, but can live a life he wants to lead.

Final Word

‘Moonlight’s grandiosity in accepting and furnishing a universal roadmap to young boys and girls suffering from identity crisis is its real victory. ‘Moonlight’ isn’t a film that is there to prey on your sympathy, to make you feel guilty; it’s a film that exists to show how people are formed, how lives can be changed, what struggles really mean to people, how we admire others, and how much a little moment can mean.

Read More in Explainers: La La Land | First Reformed | Manchester by the Sea

You must be logged in to post a comment.