‘Young Woman and the Sea’ centers on Trudy Ederle, a young woman who goes against all odds in an attempt to set a record of being the first woman to swim across the English Channel. The daughter of a butcher in Manhattan, Trudy is interested in swimming from an early age. Her mother encourages her to become a professional swimmer, while her father opposes such dreams. Living in the early 20th century, Trudy grapples with the social stigma of being a girl in sports and seeks to break the perception of women as less capable than men by completing a 35-mile swim across the English Channel, separating England and France.

The grueling challenge has previously only been completed by five men, and she finds very few supporters in her endeavor. In the directorial hands of Joachim Rønning, the thrilling sports movie transports us to a past era while exploring timeless themes of grit, believing in one’s self, and following dreams. The astounding story of ‘Young Woman and the Sea’ compels us to look further into the historical accounts behind it.

Young Woman and the Sea: The Hardest Test in All of Sports

Basing its narrative on Glenn Stout’s book of the same name, ‘Young Woman and the Sea’ is the true story of Gertrude Ederle and her historical feat of swimming across the English Channel and breaking the previous record by two hours. Adapted for film by writer Jeff Nathanson, the production captures parts of Ederle’s life that led her to embark upon the monumental challenge and the essence of a positive sportswoman who stares down seeming impossibilities with a smile. The team behind the film recognizes that much of Ederle’s tale has been lost to time and seeks a revival of her legend, which disproves the still prevalent notions of women in sports being in any way inferior to their male counterparts in matters of ability, grit, and determination.

The film looks at Trudy’s story from the lens of a sportsperson as well as that of a sister and a daughter while staying largely true to historical events. There are, however, some creative liberties, deviations, and omissions worth going over as we take a deep dive into the true story of ‘Young Woman and the Sea.’ Gertrude Ederle was called Trudy by her friends and family and began swimming at a tender age, taught by her mother at the family’s summer cottage in Highlands, New Jersey. A natural since her early days, Ederle called herself a “water baby” in reference to her affinity for swimming.

The movie’s segments of Trudy’s mother supporting her passions, therefore, have a historical basis as the young teen began to win competitions and win the admiration of her family. Trudy’s father was a butcher who had immigrated to New York from Germany and owned a shop on Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan. The film also focuses on the bond shared by Trudy and her sister, Margaret, which is also founded in truth. Margaret supported her sister very closely and was with her every step of the journey, from her school competitions to her crossing of the English Channel, when she shouted encouragement and sang songs to keep Trudy’s spirits up.

In 1924, Ederle participated in the Paris Olympics at 19 years of age. She had her sights set on winning three gold medals and was somewhat disappointed when she secured one gold and two bronze medals. The gold medal was won in the 4×100 meters freestyle relay with her teammates Ethel Lackie, Mariechen Wehselau, and Euphrasia Donnelly, setting a new world record for the event in the finals. Ederle secured bronze medals in women’s 400-meter freestyle and women’s 100-meter freestyle.

After the Olympics in France, a seemingly impossible task came to Ederle’s attention. Swimming across the English Channel between France and England was a feat only accomplished by five men in the past, and she ached to prove her mettle. In 1925, Ederle turned professional, having 29 world and U.S. records under her belt. She first made headlines by swimming 22 miles along the New Jersey coast from Battery Park to Sandy Hook in 7 hours and 11 minutes. This timing set a new world record that would last for 81 years to come and gave Ederle the credibility and confidence to undertake the greatest challenge of her life.

As a professional who seemed poised to continue breaking records, Ederle’s next challenge was sponsored by the N.Y. Daily News and the Chicago Tribune. The media houses paid her a moderate salary as she prepared herself to swim across the English Channel. Ederle took on Jabez Wolffe as a coach to train for the feat. Wolffe had attempted to swim the distance himself 22 times without success. Ederle was set to make the attempt with Olympic swimmer Helen Wainwright, who bowed out of the challenge when faced with an untimely injury. In 1925, Ederle’s first attempt at crossing the channel failed, and she was brought back after having covered part of the distance.

The reasons behind her failure are contested but can be boiled down to unpreparedness and lackluster coaching. The fluctuating currents in the channel prevent swimmers from going straight towards their target, which results in a zigzag path towards the opposite shore. Ederle wore a cumbersome women’s bathing suit of the time, typically made of wool and unnecessarily heavy for the sake of modesty. The fabric weighed her down as it absorbed water and caused chaffing. It is also speculated that Jabez Wolffe did not want Ederle to succeed owing to his own insecurities and deliberately sabotaged her attempt, ultimately pulling her out of the water too soon.

The Legacy of Gertrude Ederle

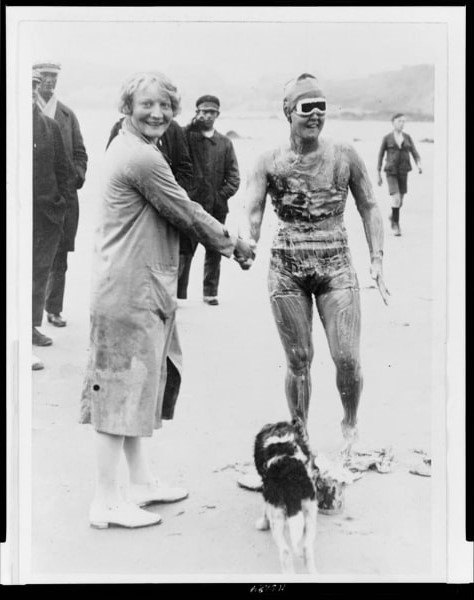

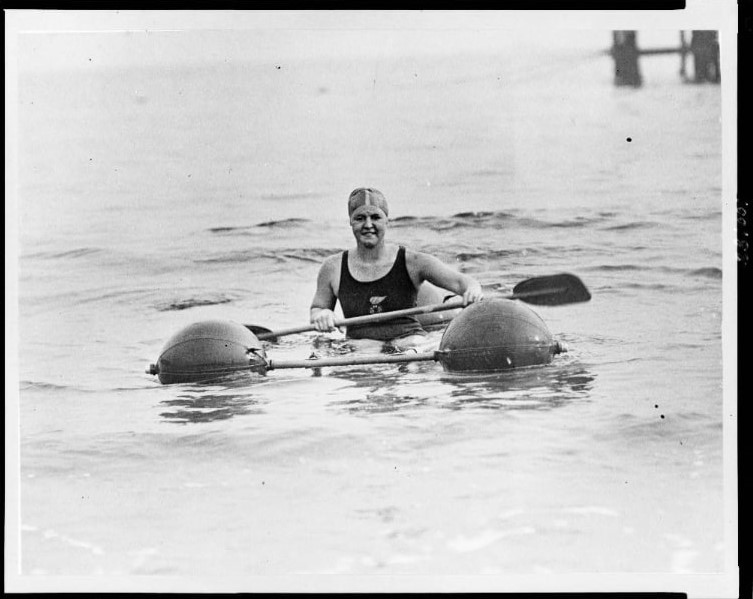

Learning from her experiences, Ederle set about making preparations for another attempt. First, she changed her coach to Bill Burgess, the second man to swim across the channel. Then, she began designing her own swimsuit and goggles. Cutting up a one-piece bathing suit, she wore a light two-piece and well-fitted goggles. She also lathered herself in sheep grease as she arrived at the French end of the channel in Cape Gris-Nez on August 6, 1926. This body coating is done to reduce the friction with water as well as between the limbs, with the grease acting as a lubricant.

Ederle dove into the water at 07:08 a.m. with a support boat packed with provisions in tow. She encountered turbulent weather, giant waves, and jellyfish schools, yet she persevered. At one point, Burgess asked Ederle to come out of the water because of the worsening conditions, but she shrugged off his apprehensions and kept swimming. Margaret was on the boat accompanying her and relayed a message from her father promising to buy her a red roadster if she completed the swim. The event was one of the first to be broadcast concurrently.

The tugboat following Ederle had a wireless machine that transmitted the developments to the media station in London, and special editions of the newspaper tracked her progress throughout the day. Thus, when Ederle arrived at the shore of England in Kingsdown, a crowd had already gathered there in anticipation. Barely pulling herself onto the beach, Ederle had bruises from the water’s constant lapping and jellyfish stings. She could barely speak, owing to her tongue being swollen from saltwater. Not only did Ederle become the first woman to swim across the English Channel, she did it in 13 hours and 23 minutes, breaking the best record by about two hours.

As she returned home, 2 million people greeted her with the first ticker-tape parade held in New York City to honor a woman. Her father kept his promise and bought her a red roadster. She was invited to the White House and met President Calvin Coolidge, who declared her to be “America’s Best Girl.” Arguably, the most famous person during that time, Ederle, was set upon by suitors with proposals for marriage. However, her fame was short-lived, and was eclipsed by Charles Lindbergh making history by flying over the Atlantic Ocean in 1927.

Then, The Great Depression hit in 1929, and Ederle was all but forgotten overnight. As she grew old, Ederle lost her hearing and never married. She met with a freak accident and was bedridden for several years. Nevertheless, she recovered and taught swimming to hearing-impaired children. Living in an old age home toward the end of her life, Ederle passed away at the age of 98 in 2003. ‘Young Woman and the Sea’ honors Ederle’s achievements and narrates a largely accurate account of her historic feat, which made an indelible mark on women’s sports.

Read More: Young Woman and the Sea: Exploring All Filming Locations

You must be logged in to post a comment.