Early Youth – a feisty period of life characterized by anxieties of acceptance, alienation and nascent emotions. Youth is the time when the craving to be routinely surprised as well as acknowledged is often met with a stiff resistance by an ever-shifting world. A milieu which strangely refuses us the fluidity of identity while itself flaunting an almost smugly inaccessible nature. It is a time when friendships don’t often turn out to be the ones originally sought while quirky infatuations keep dark fears at bay. This delicate stage of life, mired by confusion and indecision, is primarily a conquest to identify the contours and outcomes of the ability to feel selectively – to decry as well as stealthily encourage manipulation to carve out a distinct individuality.

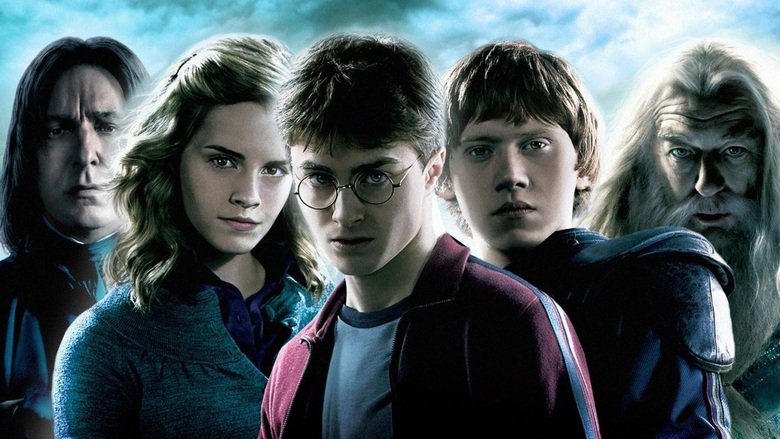

David Yates’ cinematic adaptation of the penultimate chapter in JK Rowling’s universally loved Harry Potter saga is a film skirting mounds of narrative exposition to precisely convey the trials of youth – the isolation, angst and caprice – among three inseparable friends – Harry Potter, Ron Weasley and Hermoine Granger. It pays a significant price through its aesthetic choices, ending up contradicting the saying on which entire fan fictions are based on – “God is in the details and the author is a prophet.” But is this reason enough to give the film an acutely sinister step-brotherly treatment? What if the film, in its attempt to explore its leads’ inner lives, managed to capture something more elusive than just a prolonged flashback sequence showing the rise of He Who Must Not Be Named?

JK Rowling’s sprawling series has been worthily lauded for its universally accessible themes of friendship, sacrifice, loyalty and justice interwoven skillfully with a fantastical world of magic, mystery and surreal creatures. With five Harry Potter films already inducted in public consciousness before the 2009 release of ‘The Half Blood Prince’, the expectations of ardent fans waiting to devour the imagery and texture of the macabre, fractious past of Lord Voldemort were already insurmountable. The grievous circumstances of Tom Marvolo Riddle’s birth, an insufferable childhood, a psychopathic youth spent in violently reclaiming a lost heritage and a misanthropic urge to skirt mortality itself – most of the titular villain’s past was consciously set aside, much to the ire of everyone who was even remotely invested in the book’s adaptation. What the film chose to really begin with was something more seemingly mundane – a deadpan Harry Potter (Daniel Radcliffe in the character’s shoes by now) drearily passing time in the cafe of an underground train station, until Hogwarts Headmaster Albus Dumbledore, now a frayed, old man takes him along to convince Horace Slughorn (a genial yet whimsical Jim Broadbent), a former professor, to return as Potions Master.

The lensing, camera movement and muted colors can hardly be termed as eye-grabbing, unlike Yates’ previous turn directing Order of The Phoenix (2007). They add to the film’s solemn poetry – encompassing heartbreak, disappointment and the comic drudgery of school life. As the film progresses, sometimes with an extremely delicate penchant for mood, the book seems to be followed only perfunctorily. Yet there is something which was less noticeable in previous Harry Potter films – a pervading sense of melancholy, an uneasiness which thrives amidst attenuated shadows lurking in the corridors of the Gothic castle. The historic school, for once, is hardly a magical wonder anymore. It faces an uncertain future, a dark prophecy waiting to play itself out, extinguishing the soothing candles of the Great Hall and forever shattering notions of safety and belonging. And this sense of atmospheric dread is manifested in the astounding vulnerability of a boy who’s tasked with the unthinkable – Draco Malfoy (Tom Felton).

By staging an icily antagonistic confrontation with Harry in the Hogwarts train, Draco’s inner torment as well as the compulsions which drive him are laid completely bare. Yet more layers are revealed as Malfoy grapples with failure, insecurity and the inescapable prospect of taking a life. Yet Steve Kloves’ screenplay falters in drawing strong parallels between Harry’s ambiguous obsession with a mysterious book written by the “Half Blood Prince” and Malfoy’s gradual self-destruction. It is not until the disquieting intonations of Severus Snape (Alan Rickman as sinister as ever) save Malfoy from death as part of an oath that the film hints towards an alarming possibility – Harry’s willful ignorance of humanity in the quest for revenge. The sinister undercurrents of threat and restlessness growing within the castle connote a faceless danger at every nook and corner. But that hardly stems the exuberant flow of life, even if it is cloaked in mellow trepidation.

A poignant, beautifully filmed scene in the mysterious Room of Requirement depicts a near-silent romance blooming between Harry and Ginny, where demure gestures and expressions echo more than words. It foments the visage of Hogwarts’ dichotomous nature – as a keeper of deadly secrets and wistful adolescent desire. Ginny’s brother Ron, on the other hand, played by Rupert Grint, proves to be the film’s weakest link and is reduced to droll archetype. Hermoine (a striking Emma Watson) too feels the pangs of unrequited love, until her tacit efforts are vindicated later in the film. These meandering arcs, among others, have in turn been responsible in estranging the Rowling acolyte for whom the origin story of Hogwarts’ most infamous alumnus is far more intriguing than symbolic love birds ending their fanciful flight in a forgotten corner of the castle or melodramatic talks of empty goldfish bowls and close ups of a metaphorical hourglass.

Despite these evocative flourishes lending a sense of depth, ‘The Half Blood prince’ is hardly a perfect film. An immersive soundtrack paradoxically stretches scenes beyond their desired effect rather than complement their potency. Harry’s occasional glimpses into Voldemort’s past often feel jarring and removed from immediate dramatic concerns. Even if Yates wishes to insinuate that Harry’s flippant attitude is due in part to the transience he faces internally and externally, the film shies from truly exploring a psyche adrift in teenage whimsy. When Harry is finally whisked away by Dumbledore for seeking Voldemort’s Horcrux, the film’s tonal inconsistencies come to the fore as it heads towards a fiery climax. But it is in the reinforced depiction of magic as extracting a toll on everybody who uses it for individual expression, malevolent or empathetic that the film’s ominous atmosphere is retained, albeit precariously.

Following in the book’s footsteps, the film ends on a note of devastating loss. But symbolic overtones involving soft beams of light eclipsing a morbid, inhuman mark in the cloudy skies above communicate a striking purity of bittersweet feeling. Mournful onlookers stand together in despair, but their hearts are still not devoid of hope. As Harry sulks in the futility of the tribulations he has faced, he is reminded of unconditional friendship and solidarity when Ron and Hermoine refuse to let him embark on his journey alone. The overwhelming emotion is enough for him to look out of the Headmaster’s Tower and say,” I never realized how beautiful this place was”. And by surrendering to an uncertain future in the aftermath of grief, the trio, now having come of age, finally finds the strength to move on.

You must be logged in to post a comment.