The Kathakali, one of India’s most revered classical dance forms, was developed in the state of Kerala, where it is still being practiced today. The art-form is known for its distinctive facial make-up and elaborate costumes, and I bring it up as a starting point to my article because of how subtly connected I find it to be with the art of cinema. The Kathakali is performed largely by male dancers, who act out a story by expressing exaggerated emotions on their faces to describe real human sentiments. This exaggeration is quite voracious, strikingly differentiating Kathakali from the reality that it depicts, similar to how a film following a narrative sets itself apart from reality using the essence of fiction. In fact, one can find a strange likeness in the Malayalam cinema of the formative years (pre-1970s) with the presentation of the Kathakali, showing just how influential a role Keralian culture played on Keralian celluloid. Before the Parallel Cinema Movement (the French New Wave – of sorts, of India) found a place of nourishment in Kerala, much of the films produced had an overemphasis in style, regarding their locations, stories, performances, and even make-up.

Some interesting films did come up during this early era, like Neelakuyil (1954), Bhargavi Nilayam (1964), Odayil Ninnu (1965), Chemmeen (1965), and Iruttinte Athmavu (1967); films that followed the overpoweringly exaggerated style with dramatic expressions and actions, restless cinematography, unrealistic dialogues, somewhat implausible stories, and numerous songs, though they were handled by their directors with a distinctive flair that made them a lot more memorable than the below average competition they faced upon release. Malayalam-language cinema, which is what is made in Kerala, had an objective (more-or-less) in the ’50s and ’60s to communicate strong social morals, and in their attempts to do so, screenwriters often sacrificed a good story for a three-hour value lesson that would end up reaching the wide audience. To talk about Adoor himself (now that I’ve left him out for some time), given that his relatives from his mother’s side of the family were culturally active, he had been witness to several of Kerala’s core dance and drama forms from his early childhood on, with some of them (like the Kathakali) being played out right within the walls of his household. Without a doubt, all of this must’ve influenced his craft that would come later, as he grew to become one of the greatest filmmakers India had ever seen, though he wasn’t one to conform without thought, and without international exposure working as an added inspiration.

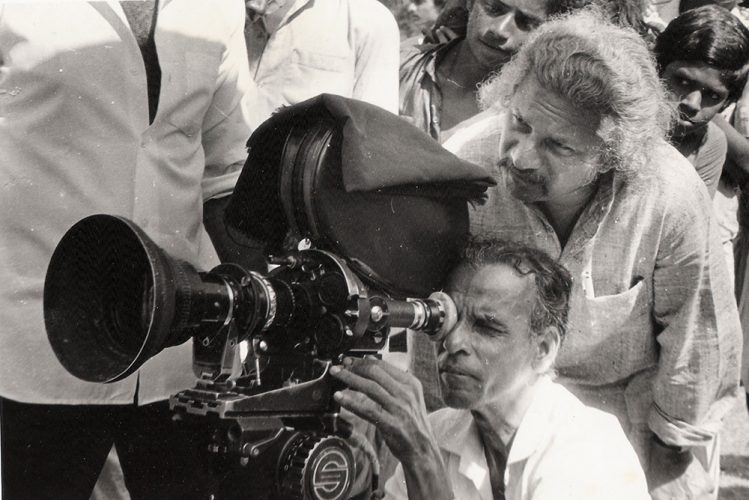

This isn’t to say that Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s cinema is simply on the other side of the equation adding up the culture and history of Kerala with international filmmaking styles and standards, but that was one of the many things he pioneered when, in 1972, he directed his first feature film, Swayamvaram (By the Choice of Oneself), which bagged the National Award for Best Film the following year. Here was a film that had no songs to accentuate character emotions or word their silent thoughts; no artificialities communicated with far and wide camera pans, tracks, and zooms (Adoor’s style, if one can define it as such, is characterized by mostly standstill cinematography, especially in those works captured by genius cameraman Mankada Ravi Varma); no dramatic emphasis on expressions and decisions; and no morals communicated. It was a film unlike anything that had come before it, relating the story of a young couple and the hardships they face when attempting to carry their lives thus forth upon their shoulders, perhaps in an attempt to justify their decision to abandon their respective houses and families, or to be more precise about it, to satisfy their personal egos. Swayamvaram presented the audience with ideas more than it did answers, and was open to interpretation, allowing the audience to think about what they had just seen.

Kodiyettam (The Ascent, 1978), his second feature, is concerned with the betterment of its protagonist, a lazy and irresponsible man who is kind at heart, but cannot survive in the society he is born into, given the duties, obligations, and practices that it has in store for him. The first Indian film to not use any background music to describe the character’s surrounding atmosphere (both internal and external), Kodiyettam‘s biggest strengths then lie in its strong writing, masterful direction, and praiseworthy lead performance (for which actor Gopi went on to win a National Award, which helped him earn the nicknames Bharat Gopi as well as Kodiyettam Gopi). In 1982, Adoor directed Eippathayam (The Rat-Trap), which is by far his most popular film. A criticism of the feudal system, Elippathayam takes the route of a dark comedy to tell the tale of a man and his three sisters, all of whom are, in their own separate ways, driven to pauses in their lives as a result of the high position that was enjoyed by their family in the society at a point of time in the past. Adoor’s usage of colors and exceptional character writing help complement – and not in any small way – his poetic lyricism, that relies on simple yet meaningful symbolism and real emotions to communicate a story of broken and confused individuals.

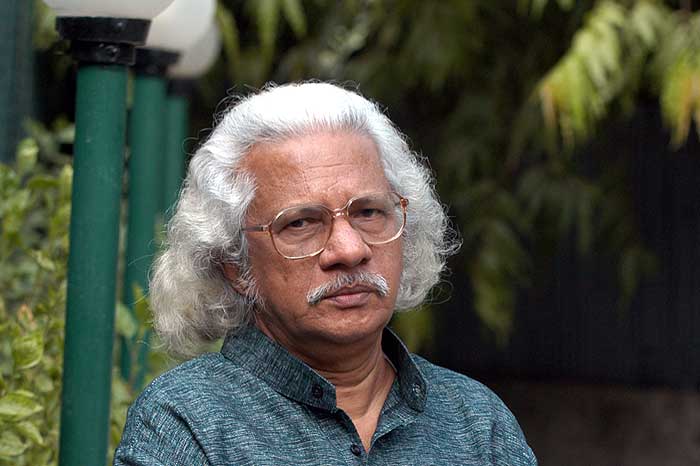

Mukhamukham (Face To Face, 1985), Anantaram (Monologue, 1987), Mathilukal (Walls, 1990), Vidheyan (The Servile, 1994), Kathapurushan (The Man of the Story, 1995), Nizhalkkuthu (Shadow Kill, 2002), Naalu Pennungal (Four Women, 2007), Oru Pennum Randaanum (One Women and Two Men, 2008), and Pinneyum (2016) make up the rest of his filmography, some of which I enjoy more than the ones I’ve discussed in the paragraphs above (I will further explain my appreciation for each of his best films in a while). Parthajit Baruah writes in his splendid book Face to Face – The Cinema of Adoor Gopalakrishnan, “His cinema is not just storytelling, but its impact goes beyond to provide a sense of awareness of the society one lives in.” This is very true when you consider the subjects that he has tackled in the best of his works: culture, custom, identity, politics (particularly Communism), social morals and practices, submission, tradition, and, though rarely, poverty, among others.

I personally admire Adoor because of how distinctive his cinema is when compared to that of other great directors of India, like Satyajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak, Mani Kaul, or Kerala’s own Govindan Aravindan, for example. While a lot of India’s best art films can be seen as inspired, either in parts or in whole, by Italian neorealism, Adoor’s topics are never just concerned with the sections of society magnified by this filmmaking standard. Rather, his focus seems to be on the people and events that he has come across in real life (notice how all the plots in his films are concerned with events that have – or could have – transpired within his lifetime), giving their stories a boost with a deeper sense of meaning, utilizing leitmotifs, innovative storytelling strategies, real emotions, and distinctive characters to send off his ultimate message, which is meticulously constructed to fit in with every individual audience member’s interpretation. Unlike other arthouse filmmakers, Adoor’s cinema never fails to strike off an emotional connection with me, because the way he uses the platform allows for an intimate understanding between the viewer and the characters on screen.

Whether it is the somber romance that revels in its loneliness in Mathilukal, or the terrifying submission on account of fear in Vidheyan, or the haunting, helpless narration of an unsound mind in Anantaram, Adoor’s films are vocal about how they are not just about ideas. They are about characters, they are about secrets, they are about tender fears that have no voice, they are about silence, they are about the most personal of human perils that are very much alive in the world around us, though, possibly out of shyness, ego, or a lack of further thought, we fail to communicate them with mere words and speech. Perhaps, this is where a medium like cinema should intervene, to provide a completeness in which we can find comfort, despite this completeness encompassing dark human truths. To quote Parthajit Baruah again, “What is distinctive about Adoor as a filmmaker is his treatment of themes and his Catholic attitude towards the world and the characters that populate his films. He has the sensibility of a writer, the craftsmanship of a playwright, and the artistry to paint the world and its figures on the canvas of the cinema screen.”

Here, I present to you six of Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s most essential films, after having seen all 12 of them, ranked purely based on my subjective appreciation of the craft, in the hopes of getting more people to know about this highly underrated filmmaker.

6. Kodiyettam (The Ascent, 1977)

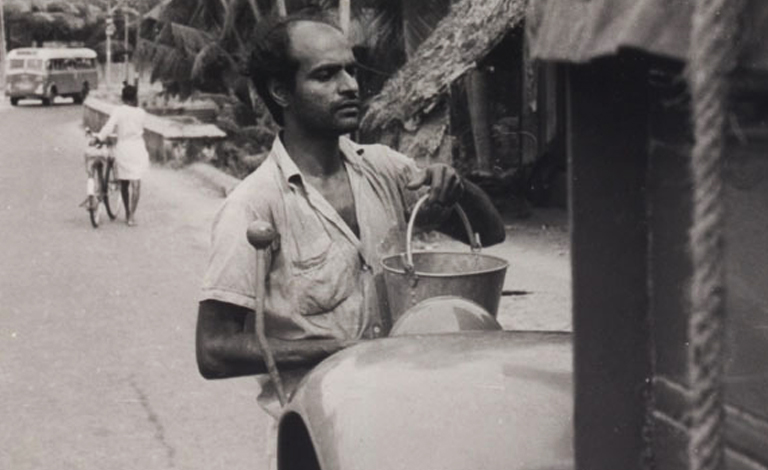

I find the terms ‘responsibility’, ‘understanding’, and ‘maturity’ difficult to define when extended to give meaning to the relationship between man and the world around him, specifically the society that he is part of. Kodiyettam tells the story of a man who lives a carefree life of an irresponsible nature, spending his days out playing cards, flying kites with children, drinking, and gossiping at the tea stall. Adoor describes him as ‘the common man’, the kind of person politicians refer to when they hand out their propositions regarding the group it is they wish to uplift and provide a better life for. The man, named Sankarankutty, sees life as something to simply be lived through without even the minutest of worries and sorrows, and this mindset of his is fueled further by his loving sister, who sends him money every month out of the little remuneration she earns from her job as a maid.

The English title of the film is ‘The Ascent’, and like it signifies, the tale of Sankarankutty’s life changes for the better after a slew of unfortunate events, which include his marriage to a woman he is probably in love with, though going by that assumption, he still doesn’t bother to find time for her, continuing to follow his old ways as if their wedding had never happened. This causes the poor woman to run away from Sankaran’s house, an action that affects the man and gets him to sit down and think about himself. Gradually, through the various people he meets and the changes he brings to his own lifestyle, he takes on the responsibilities that have been endowed upon him by society, growing further in the characteristic departments of understanding and maturity at the same time.

The film does pose the question of what society demands from the individual. Society is something that helps spread a sense of civilization, which comes with its own set of rules. Whether one follows them or not isn’t the important question being answered here, I believe. Rather, the film is a quest for happiness. How does one find happiness in the world around him? Sure, by living a carefree life and bringing no harm to anyone, you could say that receiving a sense of happiness is possible, though there isn’t any struggle behind it. Does this struggle warrant its own importance, or is this importance simply the product of human nature and its desire to compete?

5. Vidheyan (The Servile, 1994)

Like Kodiyettam, Adoor’s second adaptation Vidheyan is also a film about transformation, though rather than examining the individual, the authoritarian relationship structure is what forms the core theme of this tale. Holding under the limelight a story about a ruffian, tyrannical landlord named Bhaskar – or Bhaskara Patelar as his minions call him (out of either respect or fear) – the film examines his relation with someone whom he makes a slave out of: a runaway Keralian farmer he recruits after mercilessly harrassing him on their first meeting; by kicking him to the ground, spitting on him, calling him slurs, and finally raping his wife, just as he had started to believe that it was all over. Patelar sees a potential worker in him, and later hires him as a bartender after buying clothes for him and his wife, and promising to provide for their basic needs.

The Patel structure (from which Bhaskar was able to acquire the aforementioned tag to his name) – which was common during the early half of the twentieth century in areas like Dakshin or South Karnataka, where the film is located – sought to give unreasonable power to the richest landlords in the area, allowing them to force farmers and runaway workers into following their orders and conforming under their dictatorship, while treating them in the most inhumane of ways. Patelar’s story takes place at a point in time when the Patel structure had slowly begun to decay, limiting the extent of his unquestionable authority to a selected few lands. The slave, who agrees to work for him after being informed of the promises laid out in his favor (and after considering the disastrous results that would come from his rejection of the proposal) is in a position from where he feels it is impossible to rebel. He represents the group of runaway farmers from the Kerala district of Wayanad, who had nowhere else to go once they had arrived in Karnataka. His friends and well-wishers too advise him to “be practical”, when he talks about revolting against his master.

Once hired as a servant, the relationship between the two turns into one of excessive, even artificial loyalty. Bhaskara Patelar continues to perform his immoral activities with his trusted man by his side, and he is rarely questioned, though the protagonist finds it difficult to restrain himself when his master does things so brutally, unjustifiably wrong. Among the rights Patelar has given himself is the ability to use his servant’s wife as a sex toy, to be exploited upon his command. The poor woman’s husband can’t seem to bear it at times, and he pleads her to join him in leaving the place for good, though he is unable to answer her when she asks, “Where will we go? How far will we run?”. The man is simply helpless, because without Patelar, he wouldn’t have anyone acting as his provider.

The film turns a different direction after Patelar takes out his most diabolial of crimes yet. Saroja, his wife, is someone who understands and feels for the sorry workers under the landlord. In a lot of ways, she attempts to act as her husband’s conscience. Patelar decides to do away with her, though after having done the nasty deed, her brothers soon start looking for him, forcing him to go into hiding. Now in fear, Patelar and his trusty slave enter the depths of a thickly, dense forest, where he believes they will be safe from the clutches of those looking for him. Poignancy reigns supreme thereon, as the master and his servant are no longer within the former’s area of dominance, and are on the verge of being treated as equals between themselves. This is indicated by a scene where they share food from the same packet, for example. An exceptional critical examination of the psychology of power and submission, Vidheyan continues to live on as one of Adoor’s most widely loved works within the state of Kerala.

4. Mathilukal (Walls, 1990)

I used to wonder why the pivotal love story of Mathilukal started so late in the film, and only lasted on screen for so long. Upon a rewatch, I came to the conclusion that the film wasn’t as much about the sensuous romance as it was about the protagonist himself. Adapted from Vaikom Muhammed Basheer’s novel of the same name, the film follows a lengthy personal anecdote of the writer, recounting his experiences while in jail as a prisoner, in for the apparent crime of strongly opposing the foreign ruling government through his written works. Being something of a celebrity at the time he is taken in, Basheer is treated well not only by his fellow prisoners, but also the officers, many of who happen to take a strong liking to his work.

The film follows Basheer as he lives out his sentence in prison and, unlike the novel, attempts to dissect his character step by step along the way. Since the source material was written as a first-person narrative, it offers for little interpretation of the protagonist himself, rather going the route of describing in detail his perspective, what he sees, and how all of that affects him. Adoor paints a caricature of the intellectual artist with his depiction of Basheer in the film, as a slightly eccentric man who enjoys the time he spends alone as much as he does spending it with other inmates and guards. The admiration people have for him results in him not really being a member of any of the sub-groups within the laissez-faire enclosure. Instead, he acts as a sort of on-looker who is given the right to participate in all the circles and voice his opinions within each.

Basheer spends a lot of time talking to the plants, animals, and trees in the prison yard that he helps grow, scolding and nurturing them while holding a tone of parental care in his voice. When tragic news about the hanging of a prisoner is delivered to the writer by one of the guards, his attitude suddenly turns serious, and he responds with high-handed, empathetic thought. Clearly, Basheer isn’t like all of his acquaintances in the jail. He enjoys the silence that echoes within his own cell, but he has no trouble in conversing with and sharing the company of others at the same time. This could be why, when an order comes to set free all the political prisoners in the vicinity, with only Basheer’s name being excluded from the long list, the sudden punch in the gut from the painful feeling of realization leaves him a little depressed. He is now the only one in the prison. He is all alone.

This is when Narayani finally makes an introduction into Basheer’s life. After long years of sharing the friendship of men alone, when a woman starts a conversation with the writer after listening to him whistle one day, he is enthralled beyond measure. Separated by a huge wall dividing the prison for males and the prison for females, the two lonely souls begin talking, and their topics of discussion quickly turn intimate, giving themselves what they had been deprived of for the time that they had been inmates, though they are unable to see each other. Adoor assembles the character of Narayani as merely a voice coming from the other side, one that occasionally throws a twig over the wall to indicate to her newfound lover that she has arrived and is ready to speak.

She talks about the ugly women she shares her prison with, the black mole on her face (that Basheer can use to identify her with when they finally meet in person), and the lack of roses in their yard, and she talks about her fantasies regarding Basheer with pride, with her lover reciprocating in the same way. Theories regarding the character of Narayani are interesting, as they delve into the possibilities of her tangible existence, with a strong case being made for her just being a figment of imagination, conjured up by the creative mind belonging to the protagonist of the story. Adoor doesn’t attempt to ground Narayani’s character in either a real or fictional existence, and this ambiguity adds a layer of allure to the poetry of their romance. Basheer is, after all, alone on his side of the prison, and you can only say so much to the plants, animals, and trees.

3. Swayavaram (One’s Own Choice, 1972)

Swayamvaram is Adoor’s debut film, and upon release, it brought forth an incredible plethora of innovations to the Malayalam Film Industry. As a viewer, I have more reasons to enjoy it than just this, though. Swayavaram feels fresh in the realm of international cinema as well, incorporating a touching think-piece of a story that does not shy away from criticizing its protagonists’ actions while maintaining a level of empathy towards their plight, given that Adoor has filmed the picture in a noticeably introspective manner. The characters, while being very authentic in nature, are in fact, nothing more than the well-rounded tools of the director to mock, because it isn’t more an external struggle that they face against the society that they believe have put them in tough times than it is an internal one – one they may be very well aware of, though they abstain from talking about because of the pressure provided by their troubled egos.

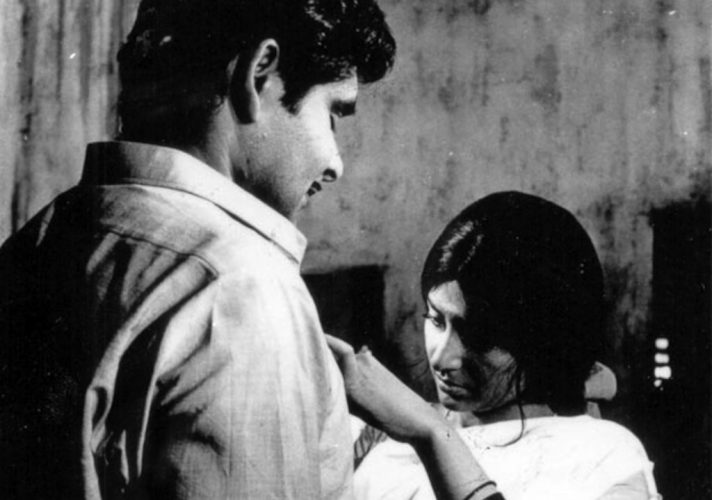

The film tells the story of Viswanathan and Sita, the counterparts of a runaway couple, who have left their respective homes and families to start a life on their own. We are introduced to these characters as they travel in a bus, perhaps their first getaway after making the bold decision they have, though within the bus, without any context, they appear to be just another couple, which is how Adoor presents them to us before getting further close as the film progresses. They are traveling away from home, with hopes and dreams that are almost completely dependent on their respective qualifications, despite the two of them being unemployed at the moment. Was their decision right? Viswanathan asks Sita this very question in between intervals in the film, and she replies firmly that it was.

Circumstances go south for the couple as things do not work out as planned. Viswanathan tries to get a job in the competitive market that doesn’t seem to respect or even consider his merits, and he is further let down when a book that he hopes to get published is shut down by an editor for being “too sentimental”. Sita, unable to find work herself, is reduced to household chores as the two move from house to house, each one smaller than the last. Was their decision right? Whatever the answer to that question may be, both of them know that there is no turning back now. All they can offer to each other is assurance that it was, while the world around them proves otherwise.

The word ‘Swayamvaram’ is of Sanskrit origin, and it literally translates to ‘one’s own choice’. Playing the role of a high-handed third person, we the audience with the crew understand that the couple has brought all that they have suffered through toward themselves with their own actions, decisions, and choices. None of them will break, none of them can break, because they want to win, because there’s an inner fire within them, and they believe it isn’t one to be put out. If that is for better or worse, the film does not answer… or does it? Without spoiling anything for my dear reader, Sita stares into the camera in one of the final shots of the film, and I read from that look in her eyes a sense of acknowledgment, regret, admittance, and helplessness. What can she do now?

2. Elippathayam (The Rat Trap, 1982)

The wall clock in the house that this film is set in is non-functional, pointing to twenty-eight minutes past six and staying there like it has been for a good long while now, and this is perhaps one of the many metaphors Adoor carefully implements in what I think is his most complex piece, Elippathayam, or The Rat Trap. A critical analysis of the matrilineal system of property sharing that once reigned supreme in Kerala, rather than address it directly, this film covers the story of three people – Unnikunju, a middle aged man, last in the lineage of a family of feudal lords; and his two sisters Rajamma and Sridevi – whose personal problems tell the much larger tale, with an air of subtlety to it all. Much of the film takes place within the house, which acts as a trap of its own, though it happens to be one planted for the humans living inside it as opposed to rats, with the bait being comfort, ego, tradition, and resistance, instead of cheese or tobacco.

As far as character writing goes, the three leads here constitute some of the best in Adoor’s entire career. Unnikunju is someone who, rather proudly, holds onto the feudal superiority cherished by his family in the decades that have now become history. A family of such status owned large acres of land, and employed a number of people to work on them, leaving the members of the household virtually jobless. Keeping with tradition, Unnikunju is an interpretation of the typical feudal karta, being lazy, irresponsible, unsocial, lethargic, and above all, fearful. His fear, I believe, stems from the fact that the present generation saw this family system at its twilight, since the world had advanced and depending upon the labour of others was no longer supported or practiced, in possibly every other place except this one house, which happened to be resistant to change. The wall clock continued to show twenty-eight minutes past six, like it had for a good long while now.

Rajamma, the elder of the two sisters who were still living at home, is unmarried like her brother, though she had begun to trample over the middle years of her life. As was custom, Rajamma carried on all the housework that had to be done, rarely receiving sunlight while going about her ways. Something of a consented slave, she performed all of the duties and responsibilities that were expected of Unnikunju, while he lay seemingly glued onto the easy chair that was out in the veranda. Some absolutely golden scenes outline their troubled relationship, like when a cow walks into their yard one morning, right outside the veranda where Unnikunju is sitting, and starts munching on the crops. Rather than doing something about it himself after taking notice, he calls out to Rajamma and waits for her to arrive in order to have someone walk up to the animal and shoo it away. Rajamma is a mute witness to her own injustice, because she believes that is what is expected of her. The various proposals she had received over the years were ignored or rejected by her brother due to the complexities of the matrilineal system. She too, is a victim of the trap.

Sridevi is perhaps the only occupant of the house that resists its bait to a degree. A college student, she gets better exposure than her siblings, frequently going out into the open and socializing with her classmates and other students. It is even hinted that she is in a romantic relationship with someone who isn’t mentioned in the film. Unnikunju has a fourth sister, Janamma, who lives separately, in a faraway house with her husband. She has escaped the trap, although she does occasionally return to the house, in order to demand her share of the family property that Unni refuses to hand over to her, on account of his personal fears. The film covers the analogical escapes made by the trapped sisters from the house, and in the process, their feudal backgrounds. By the end, Unni is left all alone, and without someone to nurture him like Rajamma present by his side, he crumbles. He crumbles as a result of his determination to have nothing changed, nothing modernized, and nothing out of his comfort zone. He crumbles as a result of his chaotic customs, and is reduced to insignificance, much like the rats that Sridevi had killed earlier in the film due to the disturbance they caused within the household. Surely Unni deserves to be done away with too… doesn’t he?

If there ever was a film that acted as a brutal warning against feeding off of society, this would be it.

1. Anantaram (Monologue, 1987)

I wrote in my description of Mathilukal about how it strays away from the source material by not employing a first-person narrative, rather conducting a character study (in third-person) of the protagonist in its place, perhaps to understand Basheer’s plight better and communicate the same effectively to the audience watching. Telling a story from this first-person perspective requires a proper understanding of the nature surrounding an individual, well enough to entrust personal comments on its elements without it in any way disturbing the objective reality that is present, unless the same is done for artistic purposes, in which case this is to be made clear to the readers or viewers in some way or the other (perhaps, by creating room for interpretation). Anantaram presents a series of monologues wherein the protagonist of the film attempts to narrate the story of his life, the way he understands it. The problem here is, unlike Basheer, he isn’t a very good storyteller, nor does he have a complete grasp of the topic at hand, despite it being his very own existence.

Though Adoor has made many masterpieces, I believe Anantaram is his magnum opus. It is the most cinematic of all his works, since its structuring is dependent upon the manipulation of a confused narrative, with the same story being told over and over again by the lead character, Ajaya Kumar (or Ajayan). As the director himself describes it, Anantaram is a film about storytelling. Particularly, how someone relates a story to another individual based on their own experiences, upbringing, likes, dislikes, etc. Different people may get excited at different intervals and give emphasis to different incidents of the same story, making the art of relating a tale completely subjective. Not all is to be believed, and not all may be told.

The character of Ajayan has every reason to be a broken soul. Born an orphan, he has only ever cursed his parents, particularly his mother, under his breath. Raised by the head doctor working in the facility where he was abandoned, Ajayan grows into something of a prodigy, being smarter and more athletic than all his peers, not to mention his talent for singing and intellectual interest in the arts. Still, he lacks many things that a child of his age would yearn for. Ajayan does not have anyone he can wholeheartedly call a best friend, perhaps with the exception of his step-brother (the doctor’s son). When Ajayan’s adopted father passes away while he is off studying in a distant college, he is informed very late, something that both disturbs and saddens him. Who was the doctor to him any way? Despite being as attached as he was, he was still only the adopted child, and he reasons the telegram received behind time, after the conduction of the rites, in this way. Now a fully grown youth, his life turns upside down when his brother gets married off to a woman, one whom he unfortunately develops strong sexual feelings for. He feels as though he should confess, as the image of this person begins to haunt his mind.

This is where the narration ends. Suddenly, Ajayan begins to tell another story, one we realize is the same as the first as he goes on relating, although this time, the incidents don’t quite match up. Not everything that happens is the same as the first, sort of like expressing the even events to a complete story after having said the odd ones, to make for a strange, twisted string of sequences. The character traits that Ajayan had assumed himself to possess in the first story are either absent or sedated here, and we see a new protagonist that we aren’t very familiar with. After telling the second story, he starts again to tell a third, at which point the film ends. Every one of these retellings is a struggling attempt made by Ajayan to communicate where exactly it was that his life went wrong, though he is absolutely helpless and cannot deliver his points the way he wants to. So he tries again, and again, and again, all to possibly no avail. It doesn’t matter though, because Ajayan’s story can be understood better by the audience than the teller, because there’s one important thing that the first-person perspective lacks, and it is an understanding of the self. With every telling of Ajayan’s life story, we grow more aware of the kind of person he is, and we learn to not fully trust his words or rely on his world-view. We learn to read between the lines, and seek the actual truth to the story.

I’ve never seen a film told in this manner before. By allowing the audience to participate in this exercise of going against the words of our narrator and creating our own sense of reality, Adoor Gopalakrishnan crafts one of the greatest mysteries of all time, incorporated into one of the greatest films ever made. His genius remains unparalleled, and his storytelling abilities mold him into a filmmaker beyond compare. I am still haunted by his best works, because they strike me so very deep, and they make for experiences that are nothing short of unforgettable.

Read More: Best Malayalam Movies

You must be logged in to post a comment.