Rebecca Hall’s ‘Passing’ is a black-and-white film that centers on two fair-skinned Black women, Irene “Rene” Redfield and Clare Bellew, who are childhood friends. As their worlds collide in 1920s New York City, the similarities and differences in their ideologies emerge and contrast sharply. The period drama sees Tessa Thompson, Ruth Negga, André Holland, Alexander Skarsgård, and Bill Camp in central roles.

The film has been lauded for its bold exploration of black and queer identities. We see how Irene and Clare are both attracted to and repelled by each other’s life choices. Their whirlwind friendship, marked by a strong queer undertone, is both beautiful and turbulent. Naturally, many are curious to know if Irene and Clare are based on real people. Let’s find out!

Are Irene “Rene” Redfield and Clare Bellew Based on Real People?

No, Irene “Rene” Redfield and Clare Bellew are not based on real people. However, certain real-life personas and incidents did inspire their characters. Hall’s directorial debut is based on Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel of the same name. Larsen — a nurse, librarian, and writer — infused her writings with her own experiences as a mixed-race woman who could pass as white. Like Irene and Clare, Larsen grew up in Chicago and then moved to New York City.

The character of Clare is a product of Larsen’s ambiguities pertaining to her racial identity. Like Clare, Larsen was light-skinned enough to pass as white. Larsen’s father was an immigrant from the Danish colony of West Indies, while her mother was Danish. Her father died when she was 2-years-old; her mother remarried and had another daughter with another Danish immigrant. Like Clare, Larsen grew up in poverty and was largely ignored by her family.

In the film, Clare chooses to abandon her Black identity and marries a racist white man, John Bellew, to attain a life of wealth, safety, and luxury. Clearly, Larsen was intimately aware of the benefits and risks of passing as white. Clare’s wild and carefree attitude also brings to mind the spirit of modernism that had gripped America during the early 20th century, imbuing many with the daring to defy societal norms.

On the other hand, Irene does not choose to pass as white in her daily life. She has a husband, Brian, who works as a doctor, and two sons, Ted and Junior. She lives a comfortable life but still faces the consequences of a racially segregated society. Irene’s fierce embracement of her Black identity, as well as desire to maintain her elite status, comes from Larsen’s firsthand observation of Black individuals at Fisk University (where she studied) and in Harlem (where she lived).

Additionally, Larsen was the wife of Elmer Imes, the second African American to earn a Ph.D. in physics, up until their divorce in 1933. She also spent a lot of time with the pioneers — writers, musicians, and intellectuals — of the Harlem Renaissance and witnessed how they wielded their Black identity for personal freedom and to fight against racism. Larsen also saw how some of the Black elite fiercely shunned racial injustice and also abandoned their cultural heritage in order to climb the social ladder.

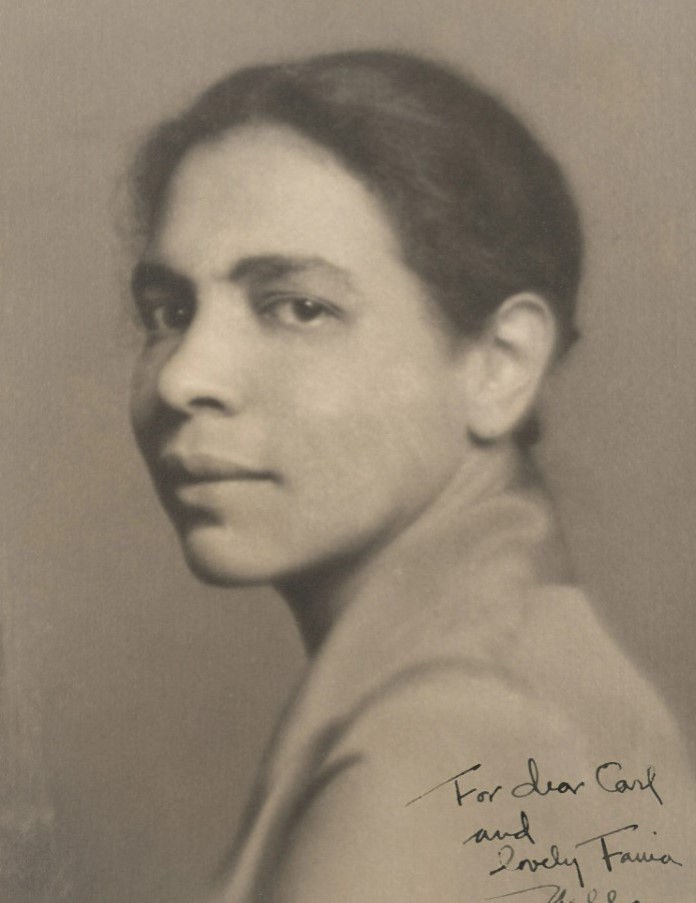

Moreover, Larsen’s friendship with Carl Van Vechten, a queer writer, photographer, and patron of the Harlem Renaissance, forms the basis of Irene’s friendship with Hugh Wentworth. Irene and Clare’s characters reveal how deeply Larsen thought about socially-mediated labels and institutions of identity — race, sexuality, marriage, motherhood, and friendship. Larsen’s milieu contributed to the two protagonists as well.

In 1924, the highly publicized case of Leonard “Kip” Rhinelander and Alice Jones brought to light the troubles of mixed-race individuals and interracial marriages. Rhinelander — a white man, hailing from a powerful New York-based family — sued Jones — a fair-skinned working-class woman — and accused her of hiding her Black ancestry in order to attain his wealth. The jury eventually ruled in Jones’ favor, but not before she was subjected to a series of humiliating body examinations meant to confirm her race.

The risk Clare takes by being married to John becomes all too apparent when one considers the fate of Jones, which Larsen was certainly aware of. Thus, Larsen’s own negotiations with her mixed-race identity inform the fictional Irene and Clare. The novelist channeled her passionate views about Black and queer identities into the two protagonists. Although Irene and Clare aren’t exactly based on real people, they certainly do represent the deliberately hidden stories of many Black individuals from America of the 1920s as well as the unstable quality of personal and social identities.

Read More: Is Passing Based on a True Story?

You must be logged in to post a comment.