All across the world east of the Atlantic, the 1960s saw a decade of indelible artistic bloom in the medium of film-making: And few provinces were so richly rewarded with cinematic treasure as the lands of Eastern Europe. From the Northern Poland, Lithuania and Russia down past Czechoslovakia and Hungary through to Balkan states like Greece, this list covers pieces both associated with and triumphantly escaping the definitions of their respective new waves- as well as significant debut pieces from great artists of their homeland. It’s a celebration of all that creative momentum: And a collection of 25 Eastern European films that are absolutely essential for fans of film in any capacity. (writer’s note: Andrei Rublev [66] was not considered for this list, as I felt it embodied a matured, formalist style and would otherwise not fit into the bounds I set for creative or debuting nominees)

25. Ashes & Diamonds (1958)

Starting off with one of the more famous names on this list, Ashes & Diamonds is an early landmark in the career of Andrzej Wajda that bookmarked his War Trilogy as a clear sounding of new cinematic talent in Poland. Whilst others capitalised on said interest more adeptly than Wajda, his piece is not underserving of its hefty heap of praise. The man makes use of effective freezes and frames situations with a keen sense of timing to deliver satisfying moments amidst what is otherwise a cinematic slog. Little about its story or characters is tapped with the same potential as the moments this director was so devoted to so despite its imagery and deservedly iconic ending- Ashes & Diamonds is confined to the top spot on this list. Seminal- but by no means masterful because of it.

24. The Saragossa Manuscript (1965)

An issue I hold against all of Wojciech Has’ undeniably essential films is the neutrality in their cinematic method. Has is so often graced with sublime literary works ripe for adaptation, as well as lavish budgets fit to accommodate even the most epic and expensive trappings, the man has nonetheless squandered so much on stylistically monotonous pictures that hold long takes at the same length and angle for each scene- every so rarely venturing into more interesting territory to occasionally prop-up the pacing of his inevitably blunted tedium. Nonetheless, whatever problems I or many others may find in his work (particularly one of the many misses for this list, 1958’s The Noose)- there is no denying the power of its imagery. Has’ grasp over finding effective locations for his actors and lazy little camera to inhabit give way to some gorgeous moments and make The Saragossa Manuscript’s 3 hour runtime more than bearable: As Napoleonic warfare gives way to fantasy and titillation all meticulously designed and brought to the screen. Whilst the tale itself isn’t nearly Buñuelian enough to become something special- the potential is there, and is realised often enough to warrant giving this film a go.

23. Passenger (1963)

What warrants Passenger’s inclusion on any Watchlist is that it is an unfinished film, released with the intention of fulfilling its deceased director’s best wishes. Andrzej Munk passed before completion of his script and thus the project was released at just over an hour long- with missing scenes vital to the plot constructed out of stills and voiceover much in the same way that Stroheim’s Greed was pieced together. What makes this fractal endeavour so special is the genuine glow the finished pieces of the film exude: Promising something great had their master not met his end. It’s a cinematic shame, for certain, but the fact we have enough of Passenger to imagine what could have been and relish in what Munk was able to give us is more than enough.

22. Night Train (1959)

Jerzy Kawalerowicz’s stripped-back story is, as with his later entry on the list, one of wasted potential. Night Train follows a set of stories unfolding on a train during its passage around Poland that spark into distrust, claustrophobia and violence in step with the speeding vehicle. Sturdily-defined characters are the fuel that keeps the ride running for a while but in the end only the culmination of its simmering drama save Night Train from mediocrity. It’s the way Kawalerowicz swoops out on the climax that gives his film its necessary bite.

21. The Sun in a Net (1963)

The Sun in a Net is notable for its place as the catalyst for the Czech New Wave- sending a ripple through the country’s cinematic landscape with its inventive aesthetics and penetrating lucidity. Comparing the look and feel of this piece to those that came before acutely demonstrates its welcome departure from formalist film-making- and is a clear spark that set aflame the creative talent of Czech film-makers that were previously just tentatively poking at the idea of modernist cinema, such as with František Vláčil and the desperately repressed talent of The Devil’s Trap in 1962. The Sun in a Net’s story is a little lacking (a theme that pervades a lot of New Wave works) but its cinematic strength and undeniable ingenuity should never be forgotten.

20. The Hourglass Sanatorium (1973)

Where Wojciech Has failed to fully extract the endless promise of The Saragossa Manuscript– he does find his feet a little easier in the latest entry on this list: 1973’s The Hourglass Sanatorium. Anchored by an extraordinarily dynamic aesthetic design and the relentlessly labyrinthine twists in its tale, Has’ finest piece of work is actually aided by his uninspired filmic technique- allowing the madness of the eponymous setting to spill out of its own accord into the expansive wides and extended takes Has favours: Giving the place a sense of space, scale and style that so gracefully injects his dying method with the kick it needs to finally make a real mark on the audience. It’s difficult to follow and harder still to piece together- but the exemplary work the artisans behind the screen did on The Hourglass Sanatorium has to be seen to be believed. A funhouse of a film that is visually exciting for every single frame.

19. The Firemen’s Ball (1967)

Before Miloš Foreman was whisked away to Hollywood to helm such classics as Amadeus and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, he was a front-runner in the burgeoning Czechoslovak New Wave- springing forth with pieces like Loves of a Blonde and then reaching the apex of this period in his filmography with 1967’s The Firemen’s Ball. It’s a refreshingly warm and comedic approach to New Wave cinema that focuses on a single event with the tact and charm that blushes in Foreman’s most famous American works- as well as a unique sense of humour that wins over the simplicity of the narrative. The key reason for its placing so high is a wonderful final shot that is both incomprehensible and utterly magical in its imagery. Humble and engrossing right through to the finish.

18. Closely Watched Trains (1966)

A work that highlights the visual distinction of the Czechoslovak New Wave, Closely Watched Trains’ strength lies in the way it moves, directed with stark understanding of design despite a clear lacking in storytelling. It’s a weak tale of a young man thrust into train conducting during a time of war and the rushed journey through adolescence such a position and time pushes upon him. Nonetheless, its sharp assembly puts it above finer plots through the waves of artistry that emanate off of its finest moments- confidence and precision in visual progression demonstrated in even the simplest moments that make Closely Watched Trains a joy to behold despite the tediousness of its tale.

17. Witchhammer (1970)

Striking like its titular hammer, Oktar Vavra’s ferocious Medieval epic sends shivers down the spine at the thought of its most intense moments, blending them superbly with a subtle sense of dread that is expertly built by the flick’s tantalising screenplay- building every word towards something hellish within the bounds of human nature. It’s a nuanced study of witch-hunting and the personal politics behind it, as well as a richly iconoclastic portrait of the Middle Ages and their brutal religious regimes.

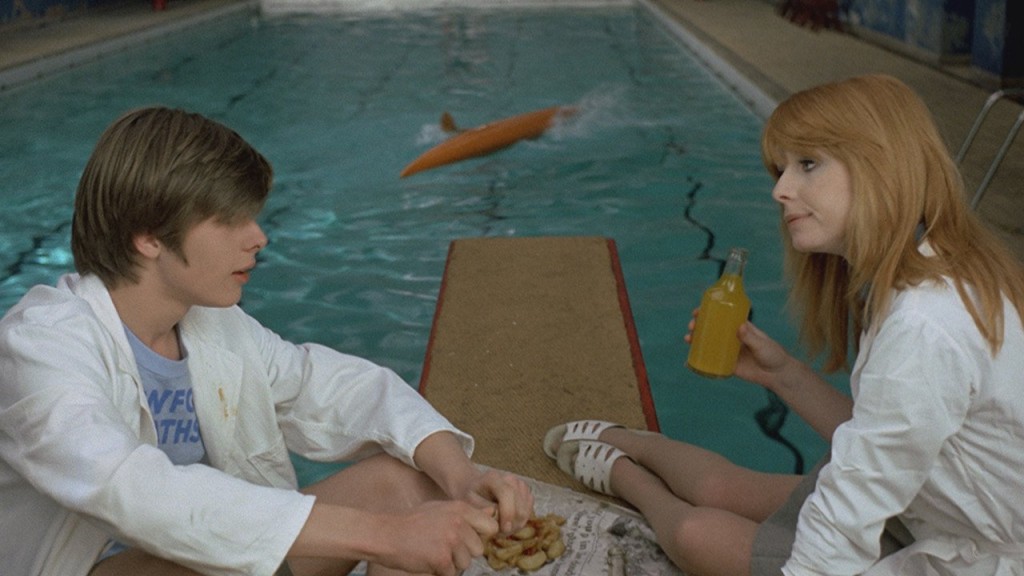

16. Deep End (1970)

Perhaps more of a British classic than a Polish one, director Jerzy Skolimowski’s sparsely brilliant meditation on adolescence is to be admired for a collection of piercing moments that succinctly further its theme with tremendous force, as well as a magnetic turn from Jane Asher. Its place as a landmark of International cinematic collaboration continues the trend set by Roman Polanski with Repulsion in 1965, one which might have eventually motivated American studios to hire Czech director Miloš Foreman. A worldly, entertaining bridge between European popular cultures.

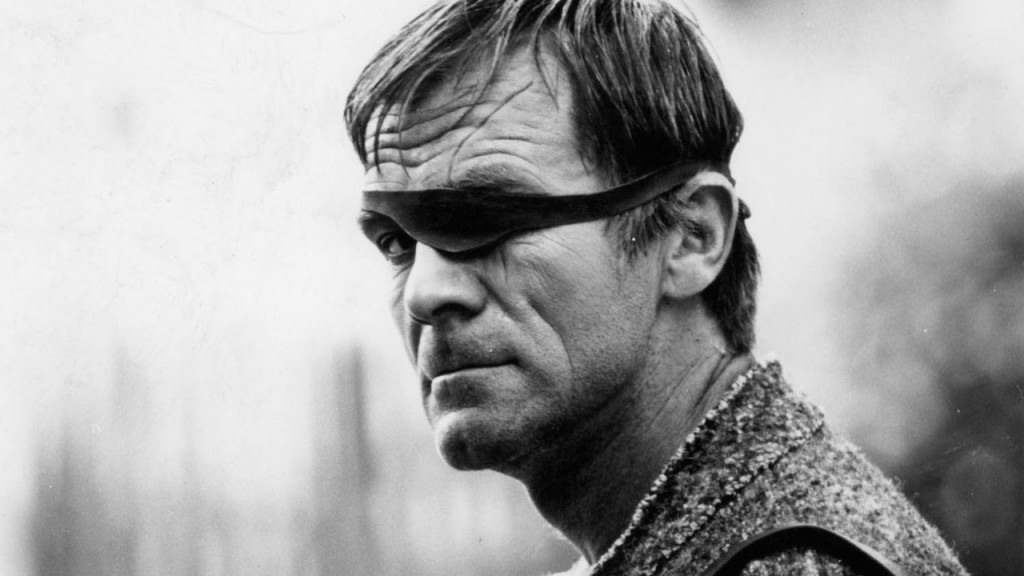

15. Mother Joan of the Angels (1961)

A ravishing portrait of demonic possession that retreats from snarling lunacy into quiet austerity swifter than you could imagine, Mother Joan of the Angels is a film fittingly torn between two identities. On the one hand it is a solemn portrait of the loneliness a priest endures passing through his time- as well as the abject and desolate landscape that plagued the people of Poland during Medieval times. On the other we have a vicious demon thrashing around with emboldened crosshairs aimed directly at female independence and the blasphemy of such an idea at the time. Free spirits wrestling with the joyless toll of tempted holy men could make for a scintillating masterpiece but Kawalerowicz loses that potential in the icy cold of his picture- glimpses of profundity frozen over. Nevertheless, it is a strong piece of work more than worthy of recognition here.

14. The Third Part of the Night (1971)

The penultimate Polish piece on this list, The Third Part of the Night marks the debut of infamously out-there director Andrzej Żuławski, whose work is notoriously difficult to get hold of. Whilst his stylistic extremity polarises, particularly his masthead Possession from 1981, Żuławski’s vision is undeniable as he gives us a glimpse into the spawning-pool of his eerie, off-kilter talents in this assured first attempt at feature film-making. The Third Part of the Night feels far more like the work of a seasoned master than many of the debuting film-makers in this list and it is such command of the medium, particularly impressive given the oddity that oozes out of every crevice of Żuławski’s work, that demands any eager viewers’ full attention.

13. The Plea (1968)

Indefinable and completely bizarre, The Plea is an extended piece of poetry that moves in a way I’ve never seen before. It is in essence most comparable to the work of Sergei Parajanov, Shadows of our Forgotten Ancestors and the Colour of Pomegranates– yet where those films utterly fail to reach their poetic potential The Plea is able to imbude its lucid narrative with grit and savagery, quietly transitioning to morbid temples of silence and darkness before bursting out into its bleak monochromatic world again in an attempt to find some purpose in its toil. The Plea is, clearly, difficult to put into words- nor would I really strive to condemn it in such a way. This is the kind of film you need know nothing about- apart from that you must hunt it down and see it whenever you can.

12. Wings (1966)

Russian legend Larisa Shepitko is famous for her marriage to Elem Kilmov (director of Come & See) as well as her own piece on World War Two in the form of The Ascent, as haunting and powerful a war film as has ever been made. The tiny moments of emotional transgression that so vividly enrichen that film are also on full display in her 1966 debut, Wings; perhaps the more complex and intelligent piece of work. Its insightful look at female mentality and human alienation is able to transport us both into the mind of its characters, as well as throw up a wall to their thoughts and feelings. One of the most emotionally sophisticated and yet starkly simple dramas of the 1960s, immediately cementing Shepitko as a crucial cinematic voice in her country and across the world for the tragically brief time she sat behind the director’s chair.

11. Diamonds in the Night (1964)

Unique even amidst every other piece of work on this list, Diamonds in the Night serves as a critical point of inspiration for many movie-makers of the time as well as a thrilling exploration into non-narrative cinema that places the importance of mood and emotion above consistent storytelling. It immediately rushes into the escape of two young men from their Nazi captors and tracks them over an exhausting passage through the wilderness desperately scavenging for supplies- with memories of their past sparked into life through the texture of the world they have been thrust into. It involves minimal dialogue and yet fleshes out both parties with a special touch that absolutely warrants experiencing Diamonds in the Night whenever you find the chance. Superb cinema.

10. Knife in the Water (1962)

Roman Polanski’s career has gone up and down, both cinematically and privately. At his best, he embodies an astute professionalism and expert command of tone that breathes through in the likes of Chinatown, Repulsion, The Pianist and The Tenant. Otherwise, many of his projects have fallen so flat you’d scarcely think such a mediocre director could have constructed some of the finest movies ever made. I say all this because, in the 1960s, Roman Polanski couldn’t be touched. He made a slew of fantastic movies that continue to be celebrated to this day and the crowning cornerstone of this cinematic bloom was his 1962 debut: Knife in the Water. He is forever one step ahead of his audience and creates a thrilling sense of progression that makes us demand an answer from a script which refuses to reveal all its cards- playing characters against eachother beautifully; all backed by an eerie, perplexing score. It’s one of the towering pinnacles that pocketmark his body of work. Damn shame the streak simply couldn’t last.

9. Reconstruction (1970)

Moving way down to the Balkans we see the introduction of Theo Angelopoulos with his thrillingly assured Reconstruction– staggeringly authoritative for its debuting place in the director’s oeuvre and filled with a stark, fresh cinematic vigour that would define the man’s earliest works. Reconstruction intercuts the police forcing an eloped couple to re-enact their murder of the husband with said couple attempting to escape, cut off at every corner by their own indecision and latent guilt. It heaves with the feeling of a nation beset by turmoil- Angelopoulos’ only film shot in an overwhelmingly bleak black-and-white- surging forward with experimental narrative techniques, powerful scenes and a fully-realized mood that reaches its peak in a superb final shot. Reconstruction is the tantalising appetiser of a film-maker who already knows the game and is ready to stun us with what is to come and Angelopoulos delivered in spades after his essential first flick.

8. Ivan’s Childhood (1962)

The final famous debut in the line of a few, with perhaps the most notable name attached to it, Andrei Tarkovsky took world cinema by storm with Ivan’s Childhood– famously impressing Ingmar Bergman in the heat of his heyday. It’s a work of absorbing creativity that introduced us to the indelible eye of Tarkovsky- making an argument for being the most photographically beautiful film on this list with lavish location work infused with his trademark love for water on screen. Ivan’s Childhood is at once a horrific meditation on the corrupting nature of war as well as a blazing fire of youth that burns despite the fear and death that seeks to snuff it out. Peppered with gorgeously directed sequences not out of place in Tarkovsky’s later, fully matured style- it’s a feast for the eyes, the ears- and the soul. Few flicks about childhood match its vibrant, visceral glow.

7. The Cremator (1969)

Juraj Herz’ sleeping giant of this competition, the director’s magnetic Dark Horse slips in at number seven entirely on the strength of its director, cinematographer and editor. Whilst The Cremator’s plot is far from lifeless, its overdone to the point of banality- and yet the talents of Herz and co. invite the viewer for an incandescently moving experience that floods your senses with morbid beauty and finds fresh fruit to squeeze in each passing scene: Inspiration after inspiration making this a visual feast that looks great and moves forward as fluidly as a hot knife through butter. A tour-de-force of cinematic appeal, The Cremator is about as much fun as you can have following around a quietly damaged, charismatic sociopath on his inevitably path to murder and madness. The meat of the meal might be repulsive- but the dish it’s served on is utterly irresistible.

6. Dragon’s Return (1968)

Eduard Grecner’s moody meditation on community and mob rule, Dragon’s Return is a film firmly planted in the upper echelons of the Czech New Wave. Grecner’s grim realisation of the titular Dragon’s tragic tale is handled with an exquisitely sensory approach, tackling the audience’s eyes and ears head on with an overwhelming assault of stark imagery, electric montage and whispering non-diegetic phantoms. What it holds over the previous pick by Uber-visual virtuoso Juraj Herz is an acutely affecting drama that emerges above the film’s style and delivers a painful, infuriating and ultimately haunting take on the devastating effects of human greed, power and violence. It hits an unprecedented balance in storytelling and stylistic strength that makes this eerie Gothic fable vital viewing not only for ‘cinephiles’- but artists attempting to form their own cinematic vision. Few directors have so vividly managed to find an effective blend and explore it to its fullest potential.

5. Diabel (1972)

Andrzej Żuławski’s criminally underappreciated and woefully inaccessible filmography reaches its earliest triumph in 1972’s glorious Diabel or simply ‘The Devil’. Painting pain, anguish and a little bit of magic with a brush far more refined than contemporary nutcase Alejandro Jodorowsky, Żuławski’s film concerns a (rat-like) figure who scuttles about in pursuit of two people desperately attempting to escape the hellish conflict that consumes their homeland. The ‘devil’s character is miraculously complex, defanged and working in what seems like fear of an even greater power- perhaps at his most vulnerable at a time where man has become even more destructive and vengeful than he could possibly influence. Each frame is steeped in foggy mysticism, arcane atmosphere and a distinct layer of fear that so ghoulishly haunts our characters until the final, cackling conclusion to their stories. It’s as good a reason as any to be excited for the Żuławski box-set currently in production that promises to be the first time his best work has been officially available outside of Poland across the globe featuring Diabel, 1981’s maniacal Possession and his ’77 shot ’88 released masterwork On the Silver Globe. Pray it comes as swiftly as possible.

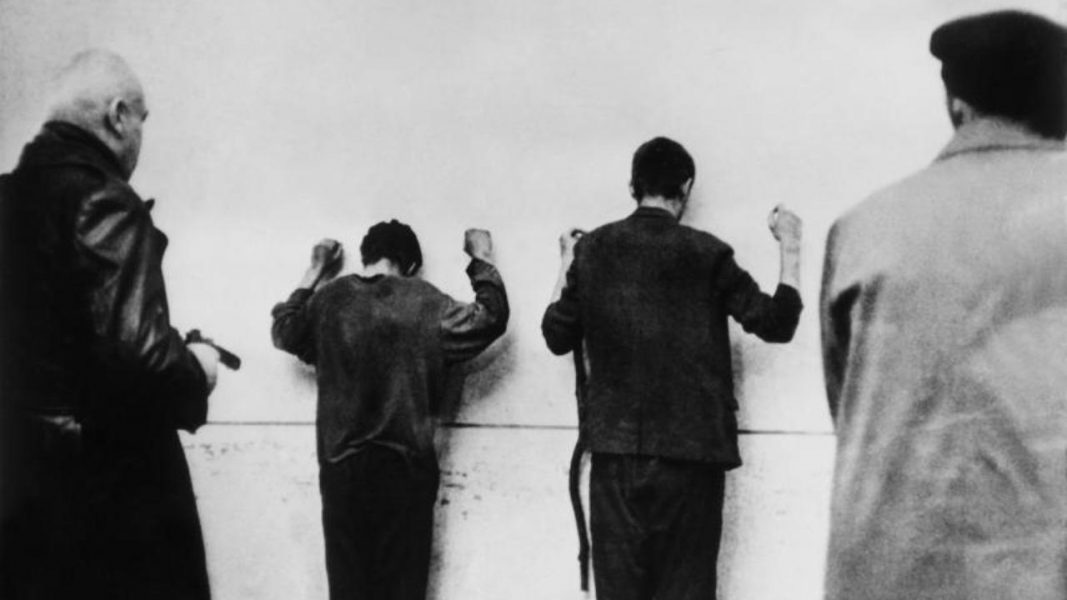

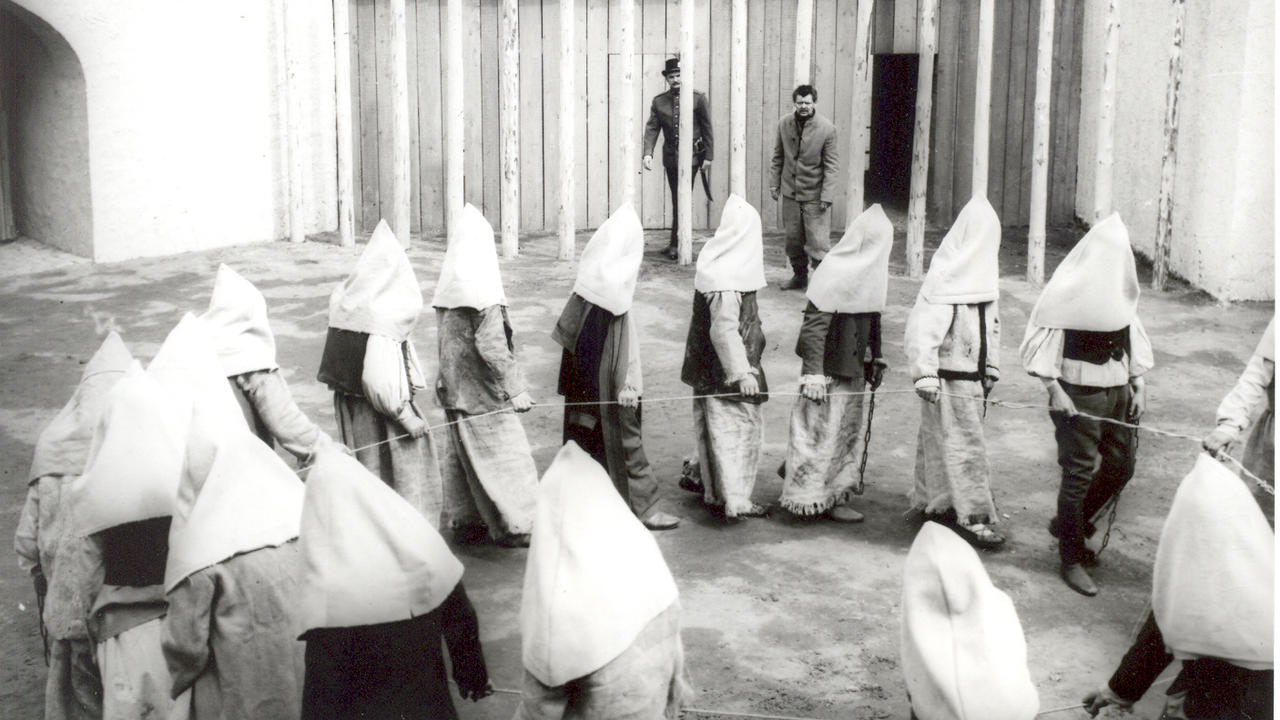

4. The Round-Up (1966)

The method of Miklós Jancsó belongs firmly on the icier side of the water when it comes to cinematic technique. Intercut with the incandescent creativity of František Vláčil, his work moves with a stark authority and inescapable sense of impending danger. Not ‘doom’. Jancsó does not allow his characters the satisfaction of palpable inevitability, instead taunting them with the possibility of that all-consuming timeless void. Death lurks purposefully around every corner of The Round-Up, a film following the inhabitants of a prison that are routinely subjected to gruelling psychological torture that goes the way of an overwhelming carnival of despair by the final movement. It’s a perfect primer to the difficult, destabilising prickliness that underlines the utter humanity in Jancsó’s work- highlighting the compelling lust for life in his films by subjecting their participants to the worst times and places imaginable. As a result, we are gifted with something just as profoundly disorienting as it was meant to be- and that is the mark of a master.

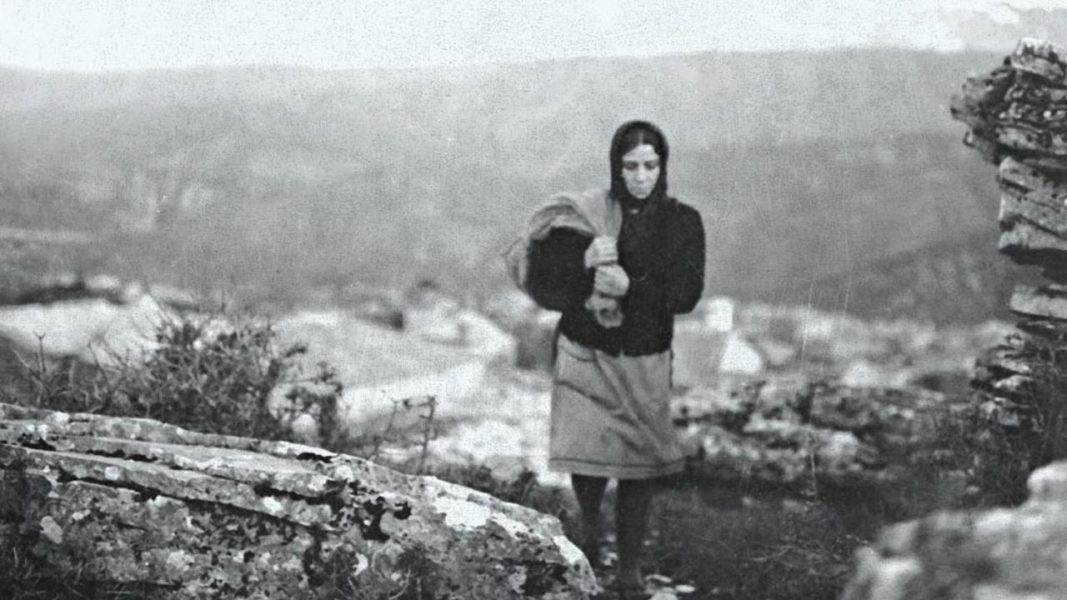

3. The Valley of the Bees (1968)

Rushing off the momentum of his previous feature, Frantisek Vláčil re-used costumes, actors and locations from his expensive Middle-Ages production to create something entirely different whilst retaining the indescribable poetry that he so sadly then failed to recapture for the rest of his career. The Valley of the Bees tracks the knights of the Teutonic Order- chronicling a life in holy servitude hotly contested by mortal desires through Vláčil’s immensely engaging cinematic eye- fragmenting space and time with the same startling power as the experimental films of Stan Brakhage or Peter Tscherkassky. A feverish concoction of Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev and the unhinged invention the Czech New Wave has already blazed through this list, it’s a step away from the freedom of his previous work but nonetheless an astonishing fragment of filmmaking. To miss it is to miss a definitive cinematic statement on the faith and madness of the Middle Ages.

2. The Red & The White (1967)

The Red & The White is so unequivocally brutal you wonder how even the man behind the torturous Round-Up could have mustered enough inhumanity to purge it from his creative consciousness. Perhaps the only definably anti-war film ever made, Miklós Jancsó’s glacial opus drifts across conflicts without the anchor of character or persona, not dissimilar to Christopher Nolan’s recently released Dunkirk. Those who call that film ‘experimental’ in its narrative should leap at the chance to experience Jancsó’s vision of a war without heroes, however, as it dismisses any traditional sense of narrative in favor of a startling series of merciless vignettes that see hundreds slaughtered in the name of… what? What drives these men, who’s only division is the colour of their uniform that is only really made clear in the film’s sharp title? Do they dream? Can savage automatons with such destructive disregard for compassion be labelled has human? As with Alan Clarke’s masterful Elephant, it is the reality of the situations presented that make them in part so impossible to process. They are real and terrifying and I wouldn’t blame any viewer for attempting to forget that anything in The Red & The White actually happened- but it did.

The inherent truth of an image with boundaries is part of what makes cinema such a compelling art form: That forces us to look at listen to a picture warranted enough importance to be confined in a box and projected across the world… and the magnitude of truth behind Jancsó’s masterpiece is utterly mortifying.

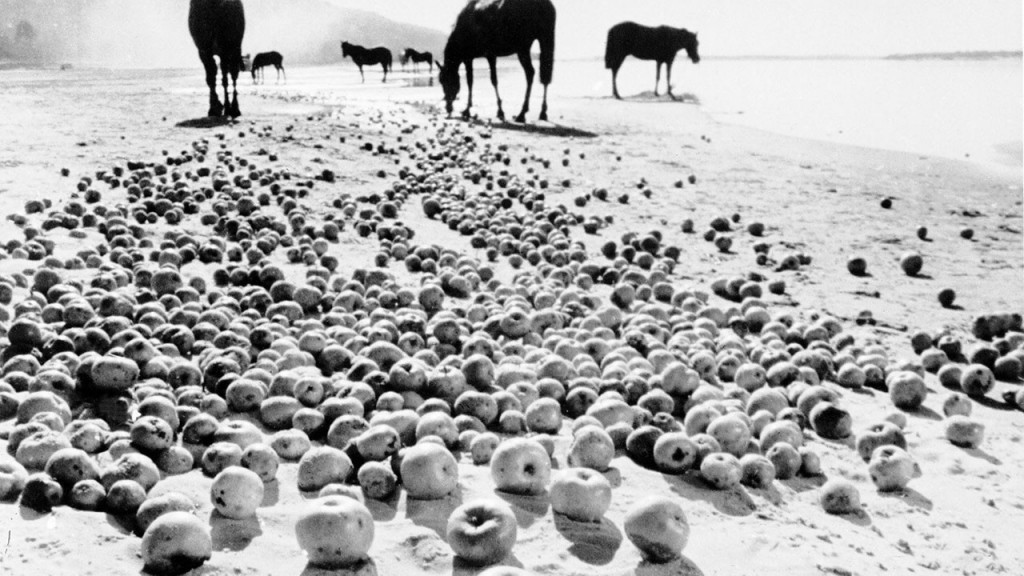

1. Marketa Lazarová (1967)

Little has to be said here, other than that Marketa Lazarová is a crowning achievement of the cinematic art form. Czech director František Vláčil’s is unparalleled, even among the greats- precisely because it invites itself to allow all the madness of the human mind. What we get is a river. A flood. The only film I’ve ever seen in my life that immediately made me sit back, straighten up and think “that was a masterpiece”. The end product of all this writing is as simple as three little words: See it. Now.

Read More: Best European Movies

You must be logged in to post a comment.