The thing that has struck me most about Chantal Akerman’s cinema is how personal it is. Not just in their plots or characters, but in the filmmaking style itself. The Belgian-born avant-garde director is known today for her exceptionally slow-moving features and detailed study of characters. What I find particularly amusing about the best of her films is how she ultimately makes them all about herself. It’s a strange sort of autobiographical feel one gets when they are subjected to her filmography. There’s something about them that’s so intimate, so sad, and so very realistic.

You begin to form a picture of Akerman as a person in your head as and when you go about her pictures: this lonely, philosophical rebel, a thinker, someone who liked to challenge the system, break rules, express her at her most private, and someone who studied the people around her a great deal. Her movies are often cold, and it’s funny the way they set a distance between the characters and the audience, because that actually allows the two to get a lot closer than they would’ve gotten otherwise. I think it is quite necessary that we look into, study, and understand (or at least try to) what we can about one of the greatest filmmakers to ever have lived, if only for the purpose of getting a better idea of the power of film, or maybe just a stronger exploration of Akerman and her thoughts.

News from Home (1977)

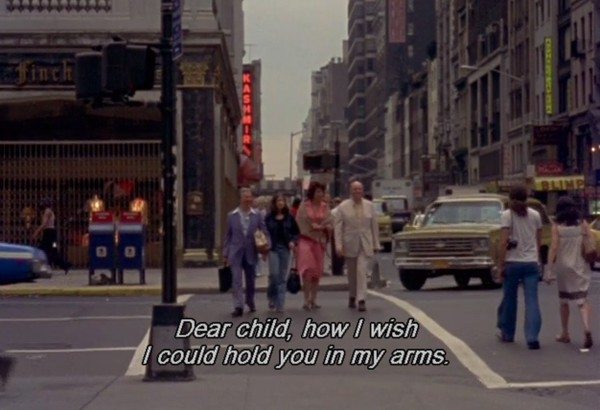

News from Home is probably the best place to start when discussing Akerman’s oeuvre. All it really is is a series of shots that show a listless New York City, devoid of personality, energy, and events. There is no background score to help aid in providing emotion to these long, static scenes, and there aren’t any characters either. We see New York in the morning, in the afternoon, and at night, and we see people we do not care about. The closest we get to a protagonist is this narrator, voiced by Akerman, who reads out the many (real) letters she received from her mother while she was in America, away from home. The narration is timely and minimal, and is quite contrary to the rest of the picture, having character, events, emotions, secrets, and zeal. Her mother writes about the family, their neighbors back home, and the weather, among other things. In the majority of her letters, she worries about her daughter living all by herself, but composes before departing, saying that despite everything, she believes in her child. The letter ends, the narration is over, and that old, dreary silence is back.

There are periods of complete inactivity and lack of distinct sounds that I so wished to listen to another one of those letters again, just to feel something, anything. Akerman doesn’t give us much to latch on to, and without those moments of narration, we’re left staring at people going about their lives, captured with fixed, straight-on angles. News from Home, with its extremely minimalistic style, becomes a film about boredom, loneliness, observation, and love. Most of all, it helps us sink so well into the shoes of a character we do not see, an expatriate living miles away from home, that it also becomes a film about Chantal Akerman, detailing how she reacts to things emotionally and defining her style as a filmmaker.

Portrait of a Young Girl at the End of the ’60s in Brussels (1994)

Akerman’s telefilm is also one of her shortest. In about an hour’s time, this movie depicts a lesbian scenario without delving into any of the cliches that surround movies about homosexuals. It’s about a young girl – as the title points out – on the verge of discovering her sexuality. She skips school one day in the April of 1968, with the ardent desire to live as carefree a life as possible. During class hours, she goes to the cinema and meets with a war deserter from Paris, in an encounter that is oddly unromantic. The two get along, him wanting to do more than just share the kiss they did, and her wanting to talk to him, uninterrupted, about her life and thoughts.

Most of this film is dialogue supported by standstill visuals of a washed up Brussels. This makes the conclusion, which is a sudden transition into beautiful silence, all the more effective. The aspects of lesbianism are dealt with subtly, there’s really no talk of it at all. It’s with the ending that something sparks in you, and you reexamine all that you saw prior to it. Akerman’s exercise in observation might perhaps be about her own life, those teenage years during which she studied herself and determined the path she was going to take. There’s really no self-talking when you go about all that, and sacrifices are definitely a by-product.

Je, Tu, Il, Elle (1974)

Je, Tu, Il, Elle is seemingly inexplicable farce, a film that appears to be a comedy about ennui and boredom. Akerman’s trademark themes of lesbianism, seclusion, and confusion are dealt with in detail here. In a lot of ways, this is the director at her sexiest, naughtiest, and most mischievous, leading me to believe that Je, Tu, Il, Elle might be her most entertaining feature. The film can be divided into three portions, based on the state of its title character, Je (or ‘I’). The first deals with her own self-implicated loneliness, in a little apartment (or just a room, perhaps), for a lengthy period of time wherein she finds the most eventless activities to partake in, including writing and rewriting a letter, eating sugar straight out of a brown paper bag, etc. The second is concerned with her escape from this time she spent alone, hitching a ride with a truck driver who shares stories of his own life, bringing out this sense of immorality that I found quite uncomfortable to sit around for. The third and final segment deals with her meeting with Elle, a woman – a friend, and possibly a past lover.

The story and direction lack a basic structure, and there are no morals passed or messages made clear. Instead, there are these thoughts circulated – thoughts about those aforementioned trademark themes, and what they mean to different people. The film is considered to be Akerman’s first masterwork, and I would wholeheartedly agree. Colored in black and white and cracking open human behavior’s shell of embarrassment, this is a true art-house piece, a strange little funny film, and a memorable experience.

The Meetings of Anna (1978)

Not only is The Meetings of Anna one of Akerman’s greatest achievements as a filmmaker, it might as well be one of the best movies ever made. I find it to be a poetic, sullen, and downright depressing look at the life of a lonely woman, and how the way she deals with people affect her emotions. Employing a style characterized by dull “filmy” colors and measured editing, the film follows its title character around (from a distance) as she partakes in conversations with different people she comes across. There’s that man with whom she cannot confide in, a stranger on a train, a concerned friend’s mother, and a previous lover. Anna as a person is built up through her connections with people. It seems there are many interested in what or who she is, but she doesn’t appear to be interested in them. A deeply enriching character study, what makes Akerman’s cinema work in this aspect is how much she leaves to the audience for figuring out themselves. The sweet, sulky fragrance of nostalgia and of romance envelope the streets and places Anna visits, which appears to be in conflict with the woman’s inner emotions.

This is a depressing piece of cinema, mainly because it is channeled by confusions and social misbehavior. Our protagonist is a woman with a lot hidden within her. She hasn’t found a platform to voice her worries in such a way that people would listen. Yet, there are those tender moments, like when a character asks her to sing, when she’s able to forget about it all, and live, really live, and be happy, if for only a while. The Meetings of Anna is sad and does not reassure anything emotionally positive, and that I think is its biggest victory. A time capsule of a classic.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels (1975)

Watching this film is as true, pure, and unique a cinematic experience as one can have. Akerman’s inspirations came from her observation of the people around her and of herself. The character of Jeanne Dielman was inspired by the genius filmmaker’s mother, as a widowed housewife with a routine life, one she finds herself hopelessly chained to. Although many of her films deal with similar themes, Akerman gives each one of her works a sense of individuality with their unique set of characters, all memorable and easy to set apart, despite them sharing a common set of problems.

Jeanne Dielman is my favorite of all her works, because it feels like the epitome of her style and presentation. Dielman is a woman who works the way she does for reasons she finds hard to explain. Maybe her timely, dedicated lifestyle is structured so because it allows her to forget her past. For three days, we follow her as she goes about her chores, making tiny conversations with her only son and people she comes across while performing her duties. Akerman’s mechanical presentation (one noticeable in every one of her works) seems to mock the title character, and the coldness further isolates the poor woman from the rest of society, being confined to the walls of her little apartment. An emotional work of art about captivity and liberation, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels is as close to cinematic perfection as we can get.

La Chambre (1972)

I don’t think La Chambre is a film that can be critiqued or evaluated in any way. It is a plotless short, a 11 minute experiment utilizing a single camera and making no cuts or edits. Though I wouldn’t consider involving it in a review of the best of Akerman’s works, I include it here because I feel this picture encapsulates her style very well, and that’s something I’m trying to perform a rough examination of through this article. Akerman depicted her many themes visually (ones like boredom, romance, and listlessness) with repetitiveness, still shots onlooking characters, and a lack of action and stimuli. All of this brought about a sense of mystery to her works, which is what I consider to be the greatest strength of her filmmaking style, because this arose out of thoughts and feelings, particularly relating to the characters involved. What are they thinking about when they sit like that, and how do they feel?, for example. Akerman’s straightforward study of characters meant a lack of explanation of thoughts and actions, so these mysteries were left in the exact ways as they were conceived: unsolved. This helped, at times, to heighten the complexity of the characters’ situations, brought about by battles that were fought internally, which made what would’ve otherwise been boring or uninteresting experiences intriguing. In this short, she puts forth a major strength of her’s as a filmmaker, which was bringing a sense of familiarity into the minds of her audience by conditioning them to repeated atmospheres.

All this film has is a revolving camera placed in the middle of a room (the titular ‘chamber’). We see a wash basin, a tea kettle, a rack, sunlight through the windows, a bed, and a girl upon it. The only thing on screen that moves is she, and the camera goes through some changes in direction to highlight the mystery of her appearance, which is different every time we lay eyes on her. It is a peculiar film, but it is only as peculiar as our curiosity surrounding the girl’s positioning of herself. Akerman, with her style, plays on the human mind. That’s how she won me over, and that’s why I consider her to be the one of the most fascinating filmmakers of all time.

Read More: 100 Best Movies of All Time

You must be logged in to post a comment.