Alejandro Jodorowsky Prullansky, the famous Chilean-French film director, poet, playwright and music composer, once said: “I have always thought that, of all the arts, the cinema is the most complete art.” I agree. In ways more than one, cinema actually is an amalgamation of all other important art forms: painting, writing and music. It can be no coincidence that cinema is also the most modern of art forms. After all, evolution of other art forms was necessary for cinema to come into existence. The fact that it remains the most popular art form almost from the moment it came into existence tells you both its strength and its weakness: it is easily accessible and therefore, more commercializable.

With that in mind, I am excited to present to you, the list of The Cinemaholic’s 100 Best Movies of All Time. Before you go on to start exploring our list of top 100 movies ever made, let’s remind ourselves again, that lists by their nature are never perfect. So, we don’t claim this to be the Holy Grail of the list of absolute best movies in the world. But what I can assure you is that a lot of research has gone behind putting together this list. Thousands of movie titles were considered and every final pick was debated. I am sure, you will find many of your favorite movies missing from the list. Many of my favorites are missing too! But instead of getting frustrated about it, take this opportunity to see the films that you haven’t seen. Who knows, you might end up discovering your new favorite(s)!

100. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

Jacques Demy colors his romantic opera with a mellowed, inordinate sophistication that comes off as a little bit hipster. But this color is not just the one on the walls, the clothes, and the umbrellas. It’s also on the cheeks of a young girl impossibly in love as she crosses the street to greet her lover and its absence when we see that face in a veil, the young girl now someone else’ bride. There is color, also, in the way people talk, or to be more precise, sing to each other. But their lyrical conversations don’t rhyme like most songs. When everything from professions of love to concerns about money is laced with indistinguishable passion, it wouldn’t do you much good to go fishing for rhyme or reason. While the film and all its melodic revelations, bolstered by Michel Legrand’s unearthly music, are heartrendingly romantic, all decisions our characters make are, like everything in life, decidedly not so.

For a plot so tediously well-known, having seen it be the basis of countless pop songs and soap operas, every frame of ‘The Umbrellas of Cherbourg’, bursting with melancholy, is alluringly fresh, unfamiliar even. You can attribute that to how genuine the emotions are, and how sincere their expression is. Operating on as humble a scale as it does, ‘Umbrellas’ devastates you with the smallest of reflections. I was dumbfounded at how substantial the impact of two empty chairs, once filled by the two lovers, could be. In Demy’s fondly made delicacy, we march in carnivals filled with ribbons and confetti, we decorate Christmas trees and give each other presents, tucking all our sentiments somewhere in the corners of our hearts, because no matter how hard someone’s absence is to bear or the past is to forget, all we can do is live in the fantasy of today.

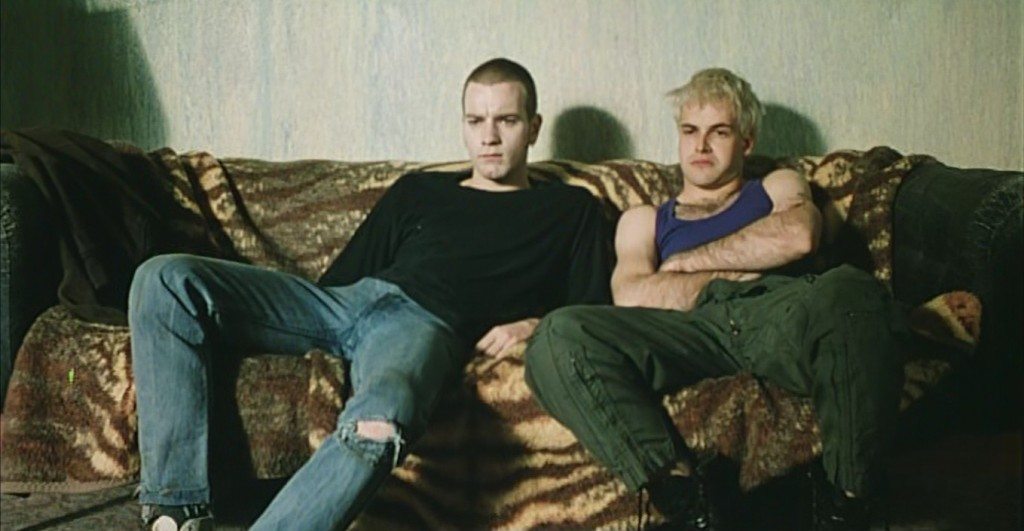

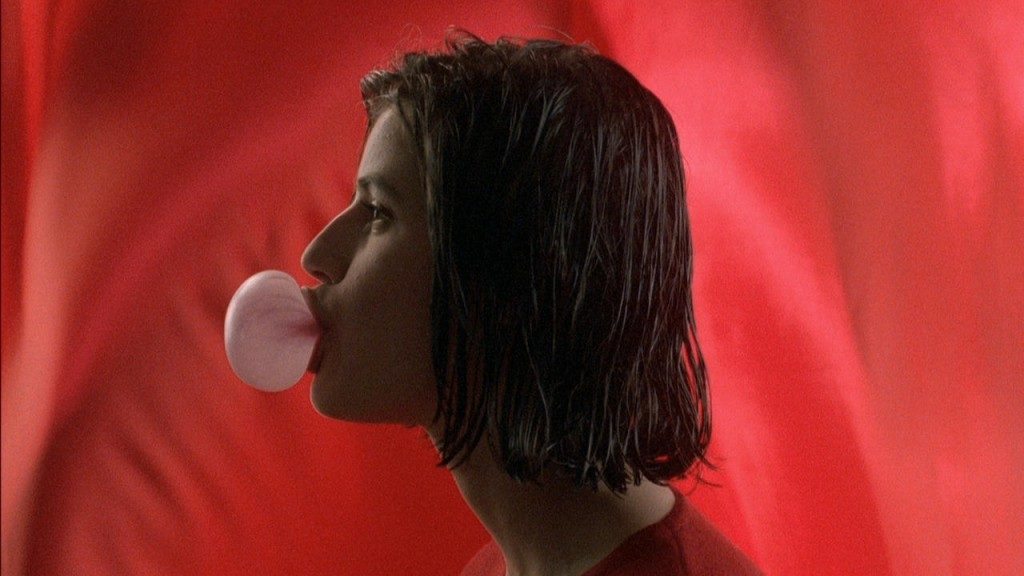

99. Trainspotting (1996)

It’s a little difficult to explain the cinephiles like ourselves about the fanaticism of ‘Trainspotting’. It came around a time, when the reality of drugs had just begun to sink in. One would say, that it glamorized drug abuse and to some extent, it’s true. The fact that came out of it, was Danny Boyle’s attempt to show the high and lows of drug abuse, without taking sides. ‘Trainspotting’ is a cult movie which tells a story of four friends and their tryst with addiction. Outrageous and bizarre are the only two words to describe it. A drug addict who wants to go clean, only to falter at each step due to his deepest of urge of getting high. Generously overdosed with humour, the film tries to underline a fact with utter seriousness: Despite the luxuries that life offers, the youth denies them with much aplomb. And the reasons? There are no reasons. “Who needs reasons when you’ve got heroin?”

98. The Graduate (1967)

Ah, the days of youth! Carefree and joyous. Fun filled with nothing to worry. No care for past, which has been left behind and no worry for future, which’s yet to come. Benjamin Braddock led this carefree life, after graduating from college. And when he finally came back to his hometown, there he met Mrs. Robinson. The flame of an affair starts burning. Life takes a devious turn when young Ben mistakes sex for companionship. It becomes topsy turvy, when he falls for her daughter. A thought provoking film, in the garb of a comedy, ‘The Graduate’ is one of funniest movies ever. Starring Dustin Hoffman, it features the iconic line – ‘Mrs Robinson, Are you trying to seduce me?’

97. The Double Life of Veronique (1991)

Perhaps no other filmmaker understood women to such profound emotional depths as Krzysztof Kieslowski did. The man just loved them and he displayed it with such passion and intimacy that you can’t help but feel enamored by its raw emotional power. ‘The Double Life of Veronique’ might just be his greatest artistic accomplishment. The film is about a woman who begins to feel that she isn’t alone and that there’s a part of her living somewhere in the world in a different soul. Veronique and Weronika are the two identical women who don’t know each other and yet share a mysteriously intimate emotional connection between them. Slawomir Idziak’s highly stylized cinematography paints the film with a tenderly melancholic feel that wraps you up and fails to let go by. There are feelings and emotions we find really hard to put into words and the film gives life to those inexplicable feelings of pensive sadness and loneliness. ‘The Double Life of Veronique’ is a stunning work of art that portrays the human soul in all its beautiful frailties and tenderness.

96. Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Many people regard cinema as an indulgence, an activity of leisure, an amusement which has no consequence in life whatsoever. But I, with an army of ardent cinephiles to fervently back me up, can state with absolute conviction that cinema is as necessary to life as life is to cinema. And ‘Cinema Paradiso’ is a beautiful, if ironic, way to make my point. Successful film director Salvatore returns home one day to the news that Alfredo has died, upon which he flashes back to his hometown n 1950s Sicily. Young and mischievous Salvatore (nicknamed Toto) discovers an enduring love for films which lures him to the village movie house Cinema Paradiso, where Alfredo is a projectionist. After taking a fancy into the boy, the old bub becomes a fatherly figure to him as he painstakingly teaches Toto the skills which would be the stepping stone for his filmmaking success.

Watching Toto and Alfredo discuss cinema with reverence, and to see Alfredo give life advice through classic movie quotes, is sheer joy. Through Toto’s coming-of-age story, ‘Cinema Paradiso’ sheds light on changes in Italian cinema and the dying trade of traditional filmmaking, editing and screening while exploring a young boy’s dream of leaving his little town to foray into the world outside. One of the best ‘film about films’ there ever was.

95. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

One of those rare film experiences that makes you feel a plethora of emotions at once. It’s funny in parts, uplifting in some and straight out heart shattering in others. It also is one of the other rare feats in simplistic, effective storytelling, telling of Randle McMurphy, a criminal who in the hopes of evading jail time, fakes being mentally ill, and pleads not guilty on grounds of insanity. Upon arriving at a mental institution, he rebels against the authoritarian Nurse Ratched (played by a steely Louise Fletcher) in a classic order vs. chaos scenario. The film establishes that there indeed is no one better to play characters with whack and charm in equal measure than Jack Nicholson himself, fetching him a deserved Oscar win for his performance in the film. What starts out as an enduring and heartwarming film, escalates to a tragic albeit hopeful ending, following disturbing scenes involving a suicide and electroconvulsive therapy on patients. The film, yet, never let’s go of the viewer’s attention and pathos for the characters on screen, evoking genuine emotion and cheer for the human spirit that emanates even in the face of unrequited authority.

94. Pyaasa (1957)

Dense with ideas of social change, and scathing commentary on the incumbent malice and stigmas of society, ‘Pyaasa’ not only epitomized the golden age of Indian cinema but also was a reflection of Indian bourgeois itself. It is a film that has a subtle quality about itself, where all of the brazen truths and harsh realities of society are simmering under the surface beneath waiting to be explored and extrapolated by the mindful audiences. ‘Pyaasa’ is a timeless classic not without reasons. Even after 60 years of its release, it remains relevant in the modern times, because India continues to be plagued by the same societal curses– corruption, misogyny, materialism — that ‘Pyaasa’ directly or indirectly addresses.

93. Modern Times (1936)

‘Modern Times’ is a humorous film with a powerful message. Carrying Chaplin’s trademark themes of hope and poverty, this picture focuses on the adverse effects machinery and other forms of technological advancements have on the common-folk, by pulling into the limelight a factory worker whose life goes through many twists and turns as he tries to cope with the new world. Though the slapstick is tear-jerkingly funny, it is all contained within a vessel of sadness. ‘Modern Times’ utilizes smart, subtle elements to ask important philosophical questions every now and then. The climax is one of the most touching ever, involving a sad form of happiness and no real answer or resolution. This film may very well be Chaplin’s best-written work, and it is surprising how relevant the ideas presented here are even today. Having undoubtedly stood the test of time, the path Modern Times takes to share its thoughts is probably the best aspect of this cinematic triumph.

92. The Thin Red Line (1998)

Terrence Malick‘s return to filmmaking from a 20 year hiatus was marked by this gorgeously stunning war drama that explores, not war, but the emotion of fighting war. The film is truly Malick-ian in nature with more emphasis laid on the visuals than the story, letting you soak in the experience of it. The genius of the film lies in Malick’s vision of seeing beauty in something as dark and gory as war. It takes an absolute genius to turn something as brutal and bloody as war into such a hypnotic experience that transcends the realities of war and instead lets you soak in on the emotions of its characters. It’s such an immersive experience that asks you to feel the human beings behind guns and bombs. These are devastated souls just like us, longing for a delicate touch, missing the warmth of the breath of their lovers and wives while having to deal with the ugliest of realities far away from them. ‘The Thin Red Line’ is quite simply an experience like no other; one that must be seen, felt and reflected upon.

91. Blade Runner (1982)

The Final Cut of Ridley Scott’s ‘Blade Runner’, I believe is the greatest dystopian movie ever made. Though Metropolis is an arguable choice, one has to observe the inauthentic visuals associated with German Expressionist Cinema. ‘Blade Runner’, on the other hand is more than perfect in building up a world that suffers from financial inequality, population boom, deficiency in anything natural because even flesh cannot be trusted here. The scintillating lighting is contextually natural, because it’s an electronic world and Jordan Cronenweth uses it similarly to the everyday illuminating objects in film noir. Though it may not pose questions as far-reaching as ‘A Space Odyssey’, but does make us wonder if “androids do dream of electric sheep”.

90. Fargo (1996)

Violent, funny, warm and brutally intense, ‘Fargo’ is one of the finest American films of the 90s and one of the greatest crime dramas ever made. The film is about a man who hires two men to kidnap his wife and extort money from his rich father in law. Coen Brothers’ brilliant use of dark humor pervades the film with an air of warmth that gives a very distinctive tone to the film. It’s this masterful blend of comedy, drama and violence that makes ‘Fargo’ such a memorable cinematic experience. That gorgeous opening shot of a snow filled Minnesota, beautifully complimented by a haunting score sets the tone for the film and establishes a sense of profound sadness that lies underneath the violence and humor the film is packed with. Frances McDormand is clearly the star of the film and steals the show, portraying a pregnant police chief caught up in a world of evil and brutalities but manages to find light and hope. ‘Fargo’ is an emotionally raw, brutally intense, endearingly funny and painfully realistic piece of pure riveting cinema.

89. Eraserhead (1977)

‘Eraserhead’ is a textbook piece on atmospheric horror. Telling the story of a man with strange hair who tries to raise a family of sorts by himself, this film turns more into a surreal nightmare with every passing minute. Using sound and close-ups to offer a sense of claustrophobic fear and aligning this with a plot that makes little sense upon a first watch, David Lynch’s debut proves to be one of the master director’s very best, which in itself is high praise. What ‘Eraserhead’ does is create a dystopian world – splattered with ugly buildings and mechanical contraptions dipped in vicious black-and-white – and throw into it characters who are more-or-less confused by their surroundings. While figuring out the “meaning” of this picture is near impossible, one must realize that this never is the intention. ‘Eraserhead’ places in the minds of its audience a feeling of utter discomfort, using both its visuals and surreal style, and finds a way to manipulate their thoughts. Only a handful of pictures are as beautifully structured yet undeniably menacing as this one, and that’s something only someone like Lynch could pull off.

88. Boyhood (2014)

‘Boyhood’ is a fond reminder of the bygone years of uninhibited joy, unwavering optimism and bubbling innocence. It relies on deriving beauty, joy and emotion out of the ordinary lives of people and not from any heightened act of drama (bread and butter for most of the movies). It’s fascinating to see how from scene to scene, not only are there changes in physicality of characters, but also you will notice the transformation in their fashion, hairstyle, taste in music, and in general, perspectives about life. ‘Boyhood’, in a way that very few films do, transcends the boundaries of cinema and becomes a tiny part of our own existence and experience. Linklater reminds us again why he is the best in business when it comes to telling simple stories about ordinary people.

87. Days of Heaven (1978)

Terrence Malick’s evolution into a fully controlled, authoritative cinematic visionary is one of the greatest things to have ever happened to American cinema. It’s clear from his early works that he was desperate to jump out of the conventional boundaries of cinema. Films like ‘Badlands’ and ‘Days of Heaven’ had seemingly straightforward narratives but these were films that tried to be something more. Something more than just a story. An experience. ‘Days of Heaven’ achieves this more brilliantly than ‘Badlands’. Many people have often criticised the film for its weak storyline. I couldn’t say they are entirely wrong but story, anyways, isn’t the most important aspect of a film. What Malick does here is use the visuality of cinema which lays emphasis on the mood of the story rather than the story itself. His intentions aren’t on making you emotional using the characters’ plight but to let you observe them, feel the beauty of the landscapes and the fragrance of its place. And to craft such kind of a viscerally moving experience is nothing short of a miracle.

86. Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

A poignant, touching film that is at par in every aspect you can think of, with the other live action films highlighting the spoils of war. This Japanese animated film centred on the horrors of World War II by focussing on the lives of a sibling pair, broke my heart in a manner no other film has managed to, and still kept on stomping on the pieces until the very end. Being a war movie, it also works wonders on the human front, beautifully realising and developing the tender relationship between Seita and Setsuko in the face of the adversity that was the Second World War. The message is loud and clear. No war is truly won, and all glory entailing victories is also accompanied by wails of innocent lives destroyed in the war. I would applaud the movie for not being overtly emotionally manipulative in making us root for its characters; but make no mistake, its powerful and uncompromising viewpoint on the war and the travesties undergone by the sibling pair will reduce you to a sobbing mess. It is THAT sad. That being said, there is no other way I would have it. It is perfection, in its most heart-breaking form.

85. Manhattan (1979)

Romance in Woody Allen’s films has always felt painfully truthful and depressingly realistic despite the deliciously poignant sense of humor he wraps them with. While ‘Annie Hall’ remains his most daring film, ‘Manhattan’ comes off as a more matured work, artistically. The film has Allen playing a bored, confused New Yorker, recently divorced, dating a high school girl but ends up falling in love with the mistress of his best buddy. Allen slightly toned down the humor for this film in order to let us truly feel the sadness engulfing his characters which makes it such an emotionally draining experience. It’s just a deeply poignant portrait of flailing relationships and flawed human beings struggling with themselves and their existence, desperately searching for happiness that they would never recognize and attain. And it’s this sweetly delicate, poignant realization of the human condition that makes ‘Manhattan’ such a powerful film.

84. Marketa Lazarová (1967)

Czech icon František Vláčil’s incorporeal dreamscape, Marketa Lazarová, is quite simply one of the most unbelievable pieces of art to come out of the 20th Century. Its avant-garde approach to cinematic language barely fits the boundaries of that often damning turn of phrase- for it is something more. A stunning fusion of sight and sound, unshackled by convention, structure or any written rule riotous cinema scholars have slapped on the film form over the years. By comparison, everything else looks so tightly controlled- so unnatural and contrived in execution. Marketa Lazarová is raw, visceral, and startlingly dynamic. In short: it’s free– a true pinnacle of the possibilities of exploring every inch cinematic medium. For that, it lies among the greatest films ever made.

83. Singin’ In The Rain (1952)

Singin’ In The Rain is the most defining musical of the Golden Age of Hollywood. It’s impossible to forget the image of Gene Kelly dancing by the street lamp, when we talk about the lustrous moments in cinema. The movie not only celebrates its own proficiency delightfully, but also the passage of cinema from being a visual medium to a resonating and stimulating one. A monumental achievement in Technicolor cinema, Kelly’s directorial effort was amusingly discarded by critics and audiences, initially. I believe the relevance of this classic grows stronger day by day, as the gap between the time periods covered by the movie (real and reel life) and the present grows increasingly. We are losing touch with an important era, and this movie swarms you with its nostalgia.

82. Don’t Look Now (1973)

It’s very difficult to find a visual art-piece that’s as hypnotic as Nicolas Roeg’s ‘Dont Look Now’. In many ways this masterpiece is like the hideous dwarf at the end. It’s beautifully draped in ecstatic coloring, but harbors the worst part of life : death. No matter how effective Sutherland’s character is, I believe this is an emotion-driven film, as Roeg places the pursuit of lost love over a conclusive story. The gothic foundation is a very powerful device to exclaim the importance of the bonds it relies on, that of paternal and familial love, as well as in giving a vague shape to the ghosts that haunt the protagonist. “Some places are like people, some shine and some don’t”.

81. Fight Club (1999)

Every once in a while, there arrives a piece of art that defines the psyche of a generation. As far as cinema goes, the 50s had ‘Rebel Without A Cause’, the 60s had ‘The Graduate’ and the 70s had ‘American Graffiti’. And even two decades on, ‘Fight Club’ fits the brooding, discontented, anti-establishment ethos of our generation like a glove. Like so many great films, ‘Fight Club’ is very divisive and can be philosophically interpreted in many distinct ways – some find it to define contemporary manhood, while others think it glorifies violence and nihilism.

Essentially a thriller, the film is told from the POV of an unnamed protagonist suffering from insomnia and discontented with his monotonous job who crosses paths with an impetuous soapmaker named Tyler Durden. Durden and the protagonist soon start an underground ‘Fight Club’ as a way for disgruntled members of the society to vent their anger. But soon Tyler’s plans and the narrator’s relationships spiral out of his control, leading to an explosive climax (literally!)

Along with the devil-may-care attitude it propagates, ‘Fight Club’ is also a hallmark of some ace direction from contemporary legend David Fincher. The sombre colour palette, sharp editing and slick camerawork has inspired a horde of dark thrillers following the film. A watershed film of the 1990s.

80. Before Sunset (2004)

Here’s the truth about human evolution that nobody will tell you: Mankind is soon going to lose the art of conversation. Technological advancements have a big side-effect: People are getting less and less interested in striking real conversation — because they have technology to hide behind. And that’s exactly why the Before Series will hold up for decades to come. A series of films that are about two people engaged in real conversation are a rarity even for this generation. In future, such films won’t get made at all. That’s why future generations are going to look back at the Before trilogy in awe and wonder. And I won’t be surprised if the trilogy finds its deserved place in not just film history but also every film school’s library.

Among the three Before films, ‘Before Sunset’ stands out because it is the most heartbreakingly beautiful. A film that is inherently about the strongest human desire: the desire to be with someone you could spend rest of your life with. If you look closely, ‘Before Sunset’, ultimately, becomes a mirror, by looking into which, you can judge your own relationships: Where you went wrong? Who was actually “the one” for you ? What opportunities did you miss? What could have been? It’s one of the rarest of rare films where your own experience in life will enrich and nourish your experience with the film.

79. The Matrix (1999)

An ingenious, clever idea rendered on screen by the Wachowskis, resulting in a film that made many viewers grow wary of the reality they found themselves in. It is true, once ‘The Matrix’ was made, there was no going back, it changed things. Not only did the film break somewhat new ground in its story, it also revolutionised the way science fiction and action movies came to be conceived thereafter. The success of ‘The Matrix’ as a movie also lies in how it masterfully dabbles between themes including philosophy, existentialism and even religion, all the while wearing the guise of an action and sci-fi flick. Neo’s ability to manipulate the simulated reality to perform seemingly impossible feats and the use of “bullet time”, an action technique that is nothing short of iconic now, adds to the film’s ingenuity. The genre may be overstuffed now, but when it came out first, it’s safe to say the audience hadn’t seen anything like it.

78. The Seventh Continent (1989)

Calling Michael Haneke’s ‘The Seventh Continent’ a horror film sounds very wrong to me, but that is how it is referred to by most people who have seen it. It’s hard to argue with them, because a viewing of this film leaves one feeling hopeless, depressed, and frightened. Having to do with a family who hates the world and life in general, this 1989 classic takes a cold and distant stance to further isolate the three players from the rest of society, which slowly but surely causes the audience to feel deeply for them as their existence takes a dark turn. Being one of the most disturbing films to ever grace the silver screen, Haneke’s debut piece taunts the viewer and never lets go. If the audience call it a horror film, then they do it referring to a scary movie that is unlike any other. Covered in ambiguity and realism, The Seventh Continent is a personal, intimate, and terrifying retelling of a true story that leaves you in silence, because for at least a couple minutes after it ends, you become unable to utter a single word.

77. Zodiac (2007)

‘Zodiac’ is not your conventional thriller; it is slow-paced and focusses more on mood and characters than plot. There is an aura that David Fincher builds so much so that you can feel the mood of the film in your bones. It is not a film that will leave you happy when it ends. It is also a film where the bad guy wins, good guys lose. And that’s why it is so good. Not just good, but a modern masterpiece. When a film manages to twitch you for full two-and-a-half hours, and leave you thinking for days, it must have got many things right that the routinely made thrillers don’t. In my opinion, ‘Zodiac’ is Fincher’s best film, where he, with his discipline and range of skills, shows why sometimes “less is more”.

76. Magnolia (1999)

‘Magnolia’ is undoubtedly Paul Thomas Anderson’s most personal work by far. The hysterical vibe Anderson infuses the film with brings a certain emotional fluidity to the melodrama that is so incredibly addictive and cathartic in its energy. The film takes place entirely in the San Fernando Valley with various interrelated characters going through different phases in their lives, struggling to deal with their own inner demons and emotional conflicts. Anderson loves these people, he knows them and understands them but presents them as unapologetically who they are; starkly naked human beings, raw and pure, confronting and overcoming their deepest fears and frailties. What makes ‘Magnolia’ so special is that it’s a film that tells so much about its filmmaker. We are given a peek into Anderson’s life, the place he belongs to and the people in his life. There is just so much of Anderson in all of the film. A film like ‘Magnolia’, had it been directed by any other filmmaker, would have felt dated and seemed pretty much like a product of its time but with Anderson it only adds to the appeal of the film.

75. Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

‘Rosemary’s Baby’ is a dark, twisted work of art that plays around with innocence in order to build a sense of horror. Having to do with a woman experiencing complications during pregnancy, the film takes a completely fresh route with its plot by allowing ritualistic elements to play a major role. There’s so much about this movie to love, starting from the well-written characters all the way to the distant brooding environment that surrounds every incident that occurs. There’s always a feeling of tension throughout the picture, and that’s partly thanks to the silent, lingering cinematography executed with Polanski’s tight directorial style. Mia Farrow gives a career-best performance here as Rosemary Woodhouse, a woman who becomes weaker as she struggles with the pains that come along with carrying a child. Overall, the atmosphere captured by this movie is matched by few others, and the way it seeps into your skin is really something else.

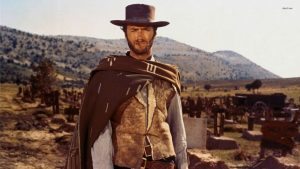

74. The Good, The Bad And The Ugly (1966)

Entrancing characters played by legendary actors, unbridled, brutal gunslinging action, hooking music and intense cinematography – the third part of the ‘Dollars’ Trilogy, said to be the birth of spaghetti westerns, is indulgent, captivating, entertaining cinema at its best. Blondie or No Name (The Good), a professional gunslinger and Tuco (The Ugly), a wanted outlaw, form an unwilling allegiance when they each find out an important detail about a stash of gold hidden by a fugitive confederate. who Angel Eyes (The Bad), a hitman, is contracted to kill. The journey of trio forms the crux of a riveting plot that ends in a classic western-style stare-down. Clint Eastwood as Blondie is the image of machismo, Lee Van Cleef as Angel Eyes is evil personified and Eli Wallach as Tuco adds a character complexity of impulse and rage to the simpler yet more showy Good Vs Evil acts of the two bigger stars. But the reins are forever director in Sergio Leone’s hands – he uses sprawling long shots and intense close-up cinematography as required to create a tension in the proceedings. A genre-defining film Quentin Tarantino, one of the greatest exponents of the modern Western, once called “The best-directed film in the world.”

73. The Travelling Players (1975)

For far too long, Theo Angelopoulos’s intimate, delicately assembled epic was known to few film enthusiasts, and perhaps, appreciated by even fewer. Its stately, gradual erection of a cinematic monument to our esoteric, cryptic relationship with time is understandably, not for everyone. But for the curious among us, it has been known to provide solace, lend wisdom and gift a perception that assists in finding constants to hang on to in this universally and cruelly dynamic world. Among the many things this film gets right is its pristine grasp of the revelations in the tale of ‘Orestes’. The mythology associated with the tragic figure is captured with a mind-numbing humility and yet, the film manages to transport us through its supple vision to a melancholic, lingering view of the mid-20th century Greece. Its temporal elegance justifies viewing history by standing next to the troupe: from the outside in. You tend to both sense the harshness of it and reflect upon its creation. It is a rare anti-fascist history lesson because it never tells us what to think. It only shows us what to feel. Angelopoulos and cinematographer Giorgos Arvanitis place us in heart-stopping locales and wash them out with the devastating viciousness of the period. ‘The Travelling Players’ is a humble, rare gem that feels as if it was saved from riot-laden streets and survived through starvation. In simpler terms, we don’t deserve it.

72. Caché (2005)

Michael Haneke is often accused of always dealing in bleak narratives. That characterization is completely unfair because what he essentially does is provide humane insights into the darkness that envelopes us all, how our flawed perceptions lead to agonizing isolation and how our delusions reduce our chances to overcome said isolation. ‘Caché’ is not only a massive, searing document that points to viciousness of the 1961 Seine River Massacre, and our inhumanity as a society, but also a poetically universal character study. Georges, our protagonist, perceives life and his presence as a social being in a distorted sense of joy. He runs away from the comfort of trusting and communicating with others. He relishes his alienation, just as he alienates so many who hold him so dear. With that, Haneke mocks the generation that wishes to be left alone. His camera is at times unusually distant, just as so many of us are in relation to our surroundings. But in his control, we have to confront our indecency, our inconsideration, our reality. One of the most challenging pieces of cinema you will ever see.

71. Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

Spanish master Victor Erice made just three feature films before retiring. Still alive today, its movies like El Sur, Quince ‘Tree of the Sun’ and especially Spirit of the Beehive, his indefinable debut, make us all wish he was still making movies. A parabalic tale of two children, one exploring his existence with innocent, often bewildering fascination and the other obsessed with the film ‘Frankenstein’ which played in their local theatre. Its mystifying portrait of the Spanish heartland is left in alluring ambiguity by Erice’s characteristically neutral direction- rarely venturing in for cinematic method in favor of silent observation. The resultant work is perplexing, engrossing and will leave you wondering about the intrinsic enigma of life itself: Its unanswerable questions, its great mysteries and their baffling unassailability. To leave you utterly devastated or incomparably moved, there is no doubt that to either extreme ‘Spirit of the Beehive’ will be an important experience.

70. All the President’s Men (1976)

Watergate. One word that brought the curtains down on Richard Nixon’s presidency and made people realise that even a person of the stature of the president can stoop down to lowest possible extent to get his things done. While the cronies of the President were busy cleaning up the mess that he created, there were two reporters who got the whiff of it. Despite looming threats, they worked tirelessly, pursued even the tiniest of the leads and at times, brought danger upon themselves in the process to get the facts to the people. Based on the book of the same name, written by reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, ‘All the President’s Men’ is an astute observation of what true journalism should be. Directed by Alan J Pakula, this was nominated for eight academy awards, eventually winning three and incidentally losing the best picture to ‘Rocky’.

69. Army of Shadows (1969)

I think an excellent point of comparison to be made for newcomers to Jean-Pierre Melville’s work is that of Stanley Kubrick. Both practice extreme technical precision and exude absolute confidence in every reel of work they put out over long and creatively lucrative careers. That being said, a cheap but challenging complaint anyone can lodge at the American director is his ‘soullessness’. A vacancy of human expression. Such is not the case with Melville. In ‘Army of Shadows’, Melville’s characters burn with a bitter despair-fuelled spark that makes their every action ooze with humanity. In the deadly world of the Wartime Resistance movement, one false move can result in utter destruction and it is with the aforementioned grace and virtuosic control over his cinema that Melville sews the seeds of a wholly believable, convincingly dead world. ‘Army of Shadows’ is one of the most quiet, intriguing and monumentally affecting pieces of work to come out of French cinema- and to miss such a criminally overlooked classic would be to do yourself a grave disservice.

68. The Shining (1980)

With his adaptation of the Stephen King classic, Stanley Kubrick created in 1980 a film that went on to redefine the horror genre. Here, it’s not just the story or the characters that birth fear. The environment and the way it has been filmed aid marvelously in allowing mind-numbing tension to penetrate the minds of the audience. The movie follows Jack Torrence, a newly appointed caretaker at The Overlook Hotel, and his family as they spend a period of utter isolation in the mysterious building. Through stunning performances and excellent camera-work, Kubrick makes sure that the contents of the film sink deep into our subconscious. The way he manipulates sound and atmosphere is absolutely incredible and creates for an unforgettable as well as spine-chilling two and a half hours. The world of ‘The Shining’ is beautifully dark, gripping you tightly by the collar during the entirety of its breathtaking third act.

67. Chinatown (1974)

There’s film noir and neo-noir and right between those two, sits Jake Gittes, dressed neatly with a crisp fedora to compliment that grin on his face. Though being a big admirer of Polanki, there’s always something that doesn’t match the end product of his films. Except Chinatown. This seminal masterpiece not only created an identity for itself, but is always looked upon by filmmakers who borrow its style to create an identity for their film. Polanski is a magician at work, tricking us with distinguishable leads as well as classic noir pacing and setting. But then comes Chinatown’s last act, which so swiftly breaks down every convention that was originally attached to similar mystery films, you’re left with an overwhelming sense of shock and despair. Its failure to beat Godfather II still puzzles me, but after half a century, people have forgotten Sicily, but never Chinatown.

66. Sátántangó (1994)

Confession number one: I almost never saw Béla Tarr’s sprawling, prodigious masterpiece. One would assume its all-time cinephile favorite status and the outstanding reputation it has amassed among American art house circles and among some of the most informed film critics across the globe would have me intrigued. But the sheer immensity of its duration (about 432 minutes) and the loris-like pace I had so enjoyed in Tarr’s ‘Werckmeister Harmonies’ seemed daunting. Confession number two: I saw ‘Sátántangó’, for the first time, in one go. I was hypnotized by its pragmatic sense of the real world and its patient, prudent sense of cinema. It observed more than it reflected and contemplated more than it delivered neatly formed statements. Its mythical, bleak realism was too good to be true and far too brutal to have been realized with such an eye for beauty.

All I wished to do by the end was to shut all my windows and envelop myself in the darkness because the film to me had been like that madman in the church and its wailing had made too much sense. Confession number three: I’m elated to report that ‘Sátántangó’s’ sagacious social and political reflections have begun to make themselves clear to me as I have returned to it repeatedly. A summer spent devouring László Krasznahorkai’s novel, which acts as source material for the film, was an especially memorable one. All I can do now is hope to keep on reaping the dividends of this happy accident.

65. The Exorcist (1973)

William Friedkin’s ‘The Exorcist’ is perfectly directed. The man is infamous for an erratic career path that sees classics fall in with shlock (and often the two groups crossing over for some fascinating explorations of cinematic shamelessness). With his best film, Friedkin decided to shoot a drama that just so happened to be about demonic possession: Sewing pathos for his complex characters and viscerally translating original author William Peter Blatty’s text trapped between belief and crippling doubt. The end result of two wonderful artists working at the top of their game to deliver a shimmering classic of American cinema: One which eclipses almost every film in its genre (bar perhaps the unconscionably horrifying ‘Wake in Fright’ or Tobe Hooper’s serendipitous tour-de-force The Texas Chainsaw Massacre). Simply stunning.

64. Suspiria (1977)

“For in our dreams, we enter a world that’s entirely our own” – J.K.Rowling. And what if one of cinema’s most twisted minds decided to spray his subconscious on a piece of film. Dario Argento’s Suspiria is considered to defy cinematic logic with its weirdly structured story. But I believe it’s a neo-expressionist masterpiece that captures the true essence of cinema, which is to make us feel truly, truly alive. Argento understands the value of space, and hence shows greater focus towards cinematography and set design, which are the dominating inhabitants of his film. ‘Suspiria’ not only represents Argento’s style but the whole of Italian horror, a genre piqued by the aesthetics of art.

63. A Man Escaped (1956)

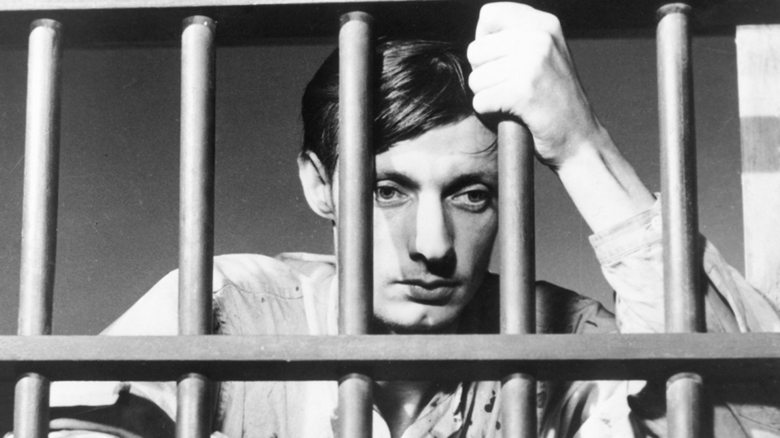

Impeccably precise and inspiringly economical, Robert Bresson’s oh so rare bullseye was struck with 1956’s ‘A Man Escaped’. The peak of the man’s mercurial powers as a filmmaker, it follows French resistance agent Fontaine’s attempts to escape an increasingly dangerous Nazi prison and finds meaning in every single frame. From the stunningly human portrayal of the lead by non-actor François Letterrier, whose sunken cheeks and blasted-out eyes so convincingly expressed the crushing weight of living in wartime, to Bresson’s minimalism managing to cultivate a searing intimacy between the audience and said the desperate man: From frequent POVs and elegant compositions that did not overindulge in techniques Bresson’s surrounding work has sometimes drowned in. I wouldn’t slash away a single frame- and thus the flick serves as an absolutely vital mode of education for budding filmmakers: To paint something so vivid and dense without it ever feeling overbearing.

62. To Kill A Mockingbird (1962)

In times like these, there’s no better film than ‘To Kill A Mockingbird’ to explain the Neo-nazis about the true meaning of caste, creed and race. Set in the timelines of a racially divided America, an African-American man gets accused of violating the modesty of a white woman. At the peak of racial injustices, when a court full of white people are baying for his blood, it comes down to one man to fight his case. One white man, named Atticus Finch. He fought valiantly to put forward the fact that all men are created equals in the court of law, be it coloured or not. His efforts go futile, as the court pronounces the man guilty. But what stays back with the viewer is the lesson that Atticus Finch inculcates into his children. That is, ‘you never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view’. Based on Harper Lee’s bestseller of the same name, ‘To Kill A Mockingbird’ is one of the greatest movies of all time.

61. Rear Window (1957)

What distinguishes a masterpiece thriller film from the run-of-the-mill sewage piled regularly upon us, is that in the latter, twists arrive in a flash, resting more on our shock than the veracity of the twist to make an impact. But in films like ‘Rear Window’, minute things evident from the time wheelchair-ridden professional photographer L.B. “Jeff” Jeffries looks out of his rear window accumulate drop by drop till they’re flooding, making the innocuous Jeff suspect that a man living across the courtyard has committed a murder. Hitchcock uses his camera masterfully like an illusionist’s tools to keep his viewers tense, fooled and guessing until the jaw-dropping reveal. Through Jeff’s obsessive stalking of his subject of interest, Hitchcock comments on the fallacies of voyeurism, how enticing it can be and the gloominess of lonely urban lifestyle which leads to it. Even more incredibly, it is as much a commentary about the viewer’s voyeurism as Jeff’s; as we’re captivated by Jeff’s captivation. Watching when not being watched is a wicked joy; Hitchcock knows it, admires it and draws us in with it.

60. 4 Months 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007)

Some films move you; some make you laugh; some break your heart. ‘4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days’ belong to a special category of films: those that make you anxious and nervous. As you would have guessed such films are probably the rarest of a rare breed. The film follows two friends who try to arrange for an abortion in the brutal Ceausescu communist regime of Romania. Visceral and uncompromising, the film grabs you by the scruff of your neck and never lets you go. Watching this film is like experiencing the gut-wrenching feeling you get when you are nervously waiting for one of your loved ones to come out of an operation theater after surgery. It is not just realistic cinema at its best; it is also one of the most life-changing movies you will ever see.

59. Last Year At Marienbad (1961)

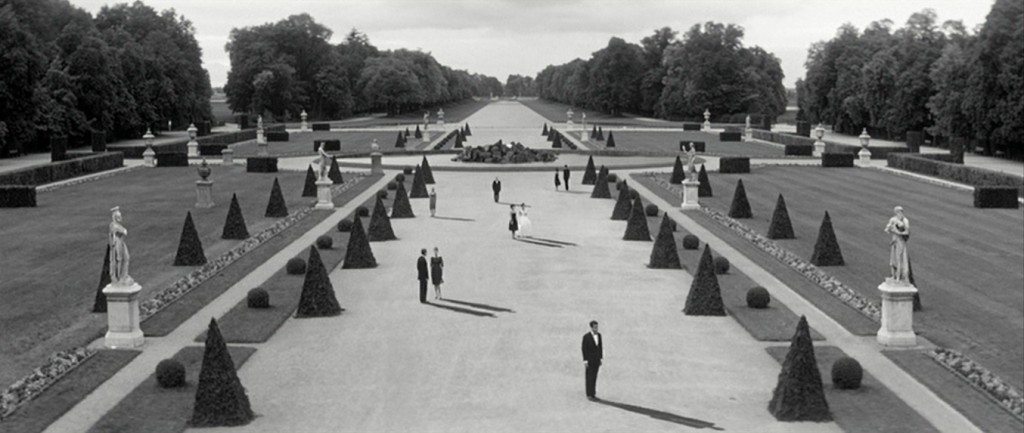

Alan Resnais’ 1961 film ‘Last Year At Marienbad’ is the closest we’ve gotten to visualizing a dream, and it’s done in as odd a manner as possible. The music that takes up the background for most of the runtime works as a sedative that puts the audience in a somnolent state. Despite this, its pretty much impossible to keep our eyes off the screen, because there’s so much going on throughout the picture, though only little is shown. I like to think of ‘Last Year At Marienbad’ as a film imagined from out the subconscious, due to its repetitive and confusing nature. The characters are confused about the bizarre world they’ve been put into as well. It is a mature and sophisticated piece, and I find the core plot – involving a man and his relation with a strange woman who he distinctly remembers meeting the year before, though she doesn’t recall the same about him – very immersive, original, passionate, romantic, dreamlike, and of course, brilliant.

58. Wild Strawberries (1957)

Ever been on a road trip where you have nothing better than to look out the window? For a certain amount of time, you gaze at the view outside, before your thoughts come rushing in and what’s outside is now just a template – it does not hold your attention anymore. So happens with Isak Borg, the protagonist of Bergman’s classic mood piece that has found its place in countless all-time best films lists, including one compiled by Stanley Kubrick in 1963. He is traveling with his daughter-in-law to receive the degree of “Doctor Jubilaris” from his alma mater. She doesn’t like him and is planning to leave his son. But our Professor, as played by the brilliant Victor Sjöström, isn’t much interested in the future. His thoughts and as a consequence, the film, catapulted by the many people he comes across his journey, cast a light only on his past. Seen through Bergman’s forgiving, assured lens, his memories are simple, familiar and human. They don’t glorify his life or reject his achievements. They are messy, like most of ours and deliberately distorted. When he finally arrives at the place to be granted the honor, we realize he never needed a reward. He already got it in those strawberries he collected with his childhood sweetheart, the merchant who remembered him, the troubled relationship with his wife, the good and the bad, the redeeming and the unforgivable. As do we, in the form of this mysterious, inexplicably moving film.

57. The Rules of the Game (1939)

Jean Renoir’s ingenious, biting comedy of manners manages to hold up surprisingly well after all these years, while remaining as playful and haunting as ever. It was shunned at the time of its release by both critics and audiences, resulting in Renoir cutting out a significant portion of the film after the disastrous premiere – a portion that mostly featured the character of Octave, who was played by Renoir himself. Hardly surprising is its growth in stature ever since. The film, in its sly, authoritative juggling of characters, themes, tones, and setting, is always deliriously entertaining, but never any less diligent or less sumptuously crafted than the best of world cinema from the period. Its scrupulously forged visuals pulsate with sophistication, but the effort is never seen and the film leaves you gaping in wonder how deeply entangled you were in its skillfully built atmosphere. Cinematographer Jean Bachelet and Renoir play with the camera in a manner that lends an airiness to the film, but their relentless control is what makes it a constantly intriguing venture. If all this doesn’t suffice, you should know that Alain Resnais once said that the film was the single most overwhelming experience he had ever had at the cinema. It would be hard to find a more glowing recommendation.

56. The Third Man (1949)

Film-noir is a genre associated with movies that lavish dark alleyways, secretive, seductive characters, a sense of mystery, and creamy black-and-white to coat it all. Though many of these pictures are intriguing and offer a good time, few try something innovative and different. The Third Man is one of the greatest film-noir ever made, because it tells its astounding story exceptionally well, making use of impressive dutch tilts, striking light, and beautiful music. The film has to do with a man and his self-conducted investigation into the murder of his financially well-off friend. The plot of The Third Man is lined with romance, dark humor, twists, and suspense. At its heart the film may be called a sweet love story, but with everything else thrown in, that infatuation is left to doubt. Playing off a masterfully written screenplay, Carol Reed’s magnum opus is one that keeps you at the edge of your seat all the way from its humble, light-hearted first act to an end that may very well be the cleverest finale to any picture you’ll ever see.

55. Cries and Whispers (1972)

Ingmar Bergman’s tragic family drama deals in a sadness that is both immaculately desperate and feverishly urgent. It’s not patiently built scene by scene and delivered on a platter by the end. You are made to inhale it from the very opening of the film which introduces the main players and their hardened, combustible sorrow with gorgeous closeups that make their stifling discomfort vividly evident. All of this is covered in an unforgiving plethora of red, in the form of the crimson that the walls of the house the story takes place in is painted with. Bergman makes us conscious of the stench of death that surrounds the women with such imposing direction that an actual death is no cause for alarm. The women’s inherently violent longing made everything in the film a haunting, blood-soaked memory in my mind. Sven Nykvist’s consistently fascinating visuals are tempered by Bergman’s subtle writing and the actors’ masterfully lived-in performances. The luminous Liv Ullman seems to mystify and enthrall every time the camera is on her, while the incredulous Ingrid Thulin and Harriet Andersson are so untarnished in their work that it feels invasive to come in contact with their feelings. Bergman doesn’t give us clear ideas to take home, but denies us all the other sensations than the ones his characters experience. We wonder how far his access to our emotions goes and he extends it at every turn. Ultimately, ‘Cries and Whispers’ is not to be believed, it is to be lived.

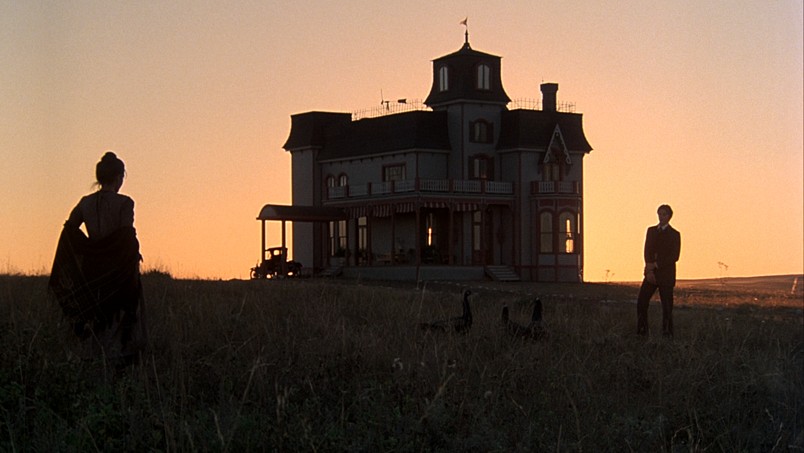

54. Once Upon A Time In The West (1968)

Maybe it’s Morricone’s haunting score or maybe Delli Colli’s vision that is as vast as the West or maybe the unflinching grit bustling in the eyes of Bronson and Fonda and maybe it is the culmination of all these aspects in almost every frame by the maestro, Sergio Leone. If you need a Western that has both the beauty of John Ford and the unforgiving wildness of Sam Peckinpah, then there is simply nobody close to Leone. In his magnum opus, he achieves what took him 3 films previously, to create a mystical world in the middle of nowhere. Though there may not be anything spiritual on the surface, the film has gods. Gods sporting crowns filled with 10 gallons of gunpowder, and grit that they swallow with water. Also, Henry Fonda’s casting as an antagonist was probably the decision of that decade, as his icy blue eyes were unlike anything the West had ever witnessed.

53. Annie Hall (1977)

No one can claim to understand the confusing, all-consuming enigma that is love like Woody Allen. And no Woody Allen film comes close to showing it in its genuine, quirky glory than this tale of Alvy Singer, a neurotic, nihilist comedian in New York who falls in ‘more than love’ with the ditzy, flighty, cheery Annie Hall, and then falls out of it. The film also explores gender differences in sexuality through Alvy’s and Annie ‘Yin and Yang’ sort of relationship. By the end, even Alvy accepts love as being “irrational and crazy and absurd” but necessary in life. The use of multiple innovative narrative techniques, such as the impromptu breaking of the fourth wall, swift alternation of past and present through smooth cuts, displaying in subtitles how Alvy or Annie feel while they actually speak something utterly different, and the addition of a ‘story within a story’ as the climax, elevate the already engaging story. ‘Annie Hall’ is probably the first truly modernist romance on celluloid and has inspired a generation of romantic comedies in its stead. None is as charming as the one they seek to imitate though.

52. M (1931)

The onset of voice recording technology, a phenomenon for which the masthead stood as 1927’s ‘The Jazz Singer’, led to an absurd saturation of dialogue in movies. The technology was taken for granted as a direct upgrade, rather than a tool to be used in conjunction with the established cinematic language. Fritz Lang, a man who began his career in silent cinema with a string of masterful works including Destiny, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, Die Nibelugen and the exceptional Metropolis. His migration to sound hit its peak in 1931’s ‘M’ – a movie which contrary to all surrounding sources had stripped out almost all ambient noise. The result is a silent talkie with an overwhelmingly lifeless atmosphere: One which so effectively underpins its narrative. The story in question strikes out at a child murderer and the incompetence of the German governance in catching him- forming their own kangaroo court to punish the killer. What Lang communicates here is of unbelievable maturity in message: The justice that deserves to be served utterly undermined by the political context of the time- with the National Socialist Party’s recorded policy of euthanasia and increasingly violent ideals manifesting as a vicious tumour on the people’s accusations. Peter Lorre’s performance, rich with pathos and tortured humanism, helps hammer home the profound deceit of ‘M’- one that remains immeasurably moving even to this day.

51. 12 Angry Men (1957)

The answer as to whether the boy was guilty or not, we will never know. But one thing 12 Angry Men does affirm is logic will always prevail over intuition, if there’s one sane man amidst a world of fools. And is foolishness a disease or merely a by-product of ignorance? Sidney Lumet’s drama doesn’t ask you to use your brain over the heart, but strive to reach a point where you can make a decision, with both working in tandem. Along with its riveting screenplay, that sits proudly in the curriculum of every film school around the world, the camerawork and staging are right out of a Japanese New Wave classic. Boasting of an unforgettable performance from the ensemble cast, 12 Angry Men is a monument of American Cinema.

50. City Lights (1931)

Not a lot of early filmmakers have the recognition and popularity in today’s culture that Chaplin enjoys. This could be because of many reasons. His films speak to the everyman and are gut-bustingly hilarious, but more than that, his stories look at melancholic situations in a humorous light. Such is the case with what is probably his most personal picture, ‘City Lights’, which tells the tale of a tramp and his efforts to impress as well as help out a poor blind flowergirl. He does so under a facade, pretending to be a rich man in order to grab her attention, but runs into trouble while doing so. When a movie continues to be just as funny and touching in the present-day as it was over 75 years ago, that usually means there’s something it’s doing right. ‘City Lights’ has left its mark on the world with its depiction of poverty and life during the hard years of the Depression, which is so well-executed and felt that it never fails to move the audience, all the while giving them hope of a better tomorrow.

49. Come & See (1985)

The latter half of an unbelievably skilled film-making team, director Elem Kilmov was married to Larisa Shepitko- the luminous virtuoso behind ‘Wings’ and ‘The Ascent’. When she so sadly died in a car accident, Kilmov finished work on her exceptional unfinished project ‘Farewell’ (which could just have easily taken this place)- and I think what makes all this context so powerful is the way the man’s grief bleeds into every frame of his work. Kilmov’s cinema seethes with unexpressed rage and desperation: Hulking in its own overwhelming weight of emotion- and few films ever made have pulsed with as powerful a feeling as Come & See. Arguably, the best war movie ever made, its hellish depiction of the Wehrmacht invasion of Belorussia echoes with deafening explosions, nightmarish visuals and a world slowly being drained of life- its scenes shot in a gorgeous, hollow light. Yet in all of this anguish, Kilmov finds his way to understanding in its transcendentally mature conclusion. Perhaps, in his commitment to contemplating the in-transience of life, he is finally finding the strength to bury the bones of his late wife. One can only hope.

48. The Seventh Seal (1957)

From the very first images of Bergman’s iconic document on faith, fear, and contentment, there is a spell cast on you. The stark, grainy look at the sea, the coast and on it a courageous knight and his fateful encounter with the personification of death defines the film’s clarity of objective, even if it leaves scope for a seductive, almost terrifying ambiguity to be present constantly. Benefiting from a magnetic performance from the incomparable Max von Sydow and a band of actors who elevate Bergman’s astonishing material, based on his play, “Wood Painting”, to unexpected levels, ‘The Seventh Seal’ in its meager 90 minutes has the influence of an old fable passed down through generations that propels imagination far more expansive than it itself can hope to contain. Gunnar Fischer’s sparkling, crisp black-and-white ensures that the harrowing intensity crawls under our skin. The stream-like fluidity is a result of a narrative unfurled with sublime confidence and a tangible levelheadedness. It may be a thoroughly simple story, that nonetheless harbors valuable ideas in its bosom, but it is sewn with a fabric so intricate and bold, you can’t help but look at it over and over for it to translate into a lasting memory.

47. La Dolce Vita (1960)

Fellini’s cautiously, patiently and poetically softened virtuoso is on full display in his Palme d’Or winner that in its soulful and shadowy glamour captures a way of living that seems too elusive and in some ways, far too real. Its pace underlines the protagonist’s sense of aimlessness and compels us to bathe in the symphonic arrangement of the vibrancy of life and how fleeting it all is. This protagonist is played by a career-best Marcello Mastroianni, who employs this gift of time to fill his eyes with an irresistible world-weariness. Questioning the significance of certain sections of ‘La Dolce Vita’ that may seem devoid of philosophical import or narrative relevance is to reject the possibility of letting the piquant details wash over you and then contemplate the consequences. As Nino Rota’s heavenly score carries us into the dizzying world of Rome, as seen through Fellini’s illusory eye, you see only what he wants you to see and it swiftly becomes what you want to see too.

46. Psycho (1960)

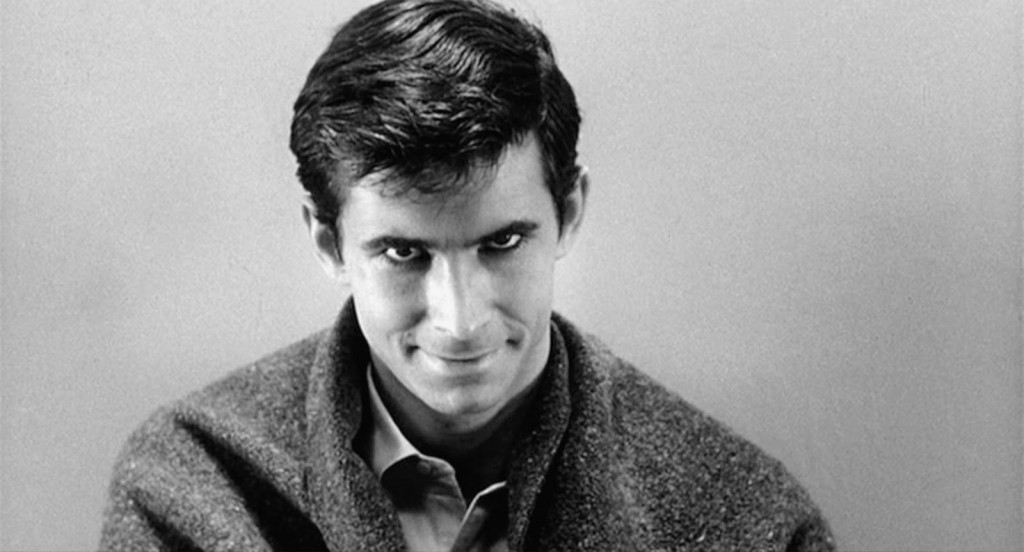

Human beings, at best can be described as peculiars. The human mind which is capable of many astounding things, is also capable of degenerating itself to beyond comprehension. Alfred Hitchcock’s ’Psycho’ does not need introductions as it holds its head high, in the midst of timeless cinemas. Apart from being a classic, it’s also a sad commentary on the failing moral of human beings. And it’s not Norman Bates mind you! The caustic hold of Mrs. Bates that set Norman’s life into doldrums right through his childhood and eventually adulthood is a reminder of how love can be suffocating. Famously, Mr.Hitchcock adopted strange policies for ‘Psycho’, which included not to allow late entrants into the movie. It was adopted to ensure full justice to the pulsating climax scene of the movie. A thriller to its truest form, ‘Psycho’ is a story of a son, his mother and their unhealthy bond of possessiveness. Hitchcock was so fiercely guarded about the finale, that he promoted the movie this tag line – “Don’t give away the ending – It’s the only one we have!”

45. Solaris (1972)

Tarkovsky’s ‘Solaris’ is quite like the phenomena depicted in the movie. From puzzling me with its deep rooted concept, to evolving into an entity that I cannot part ways with, it’s an experience that makes me wonder about the oblivious nature of every molecule that constitutes the universe. We maybe aware of the scientific dimensions, but can any instrument calculate the amount of love or sorrow one holds in a nanogram of the heart? Can anything find the brain cell where an unforgettable memory resides? From Bach’s spellbinding music in the opening sequence to the perennial highway scene, Tarkovsky’s use of time to detach the viewer from the functioning of a normal world is masterful. Solaris is a realm where emotions send you for a spin with insanity, but who wouldn’t emote when insanity is beautiful to touch, and visceral enough to absolve you from your own self.

44. Schindler’s List (1993)

An important film that greatly benefits from Spielberg’s flair for the dramatic, it is an equally disturbing and sensitive experience unto itself. The film is, like many others on this list, a masterclass in something I like to call simplistic, impactful storytelling. The narrative follows Oskar Schindler, a German businessman who saved the lives of more than a thousand Jews by employing them in his factories during the Holocaust. All the three leads, Liam Neeson as Oskar Schindler, Ralph Fiennes as Amon Goth and Ben Kingsley as Itzhak Stern are in terrific form, turning in the most sincere of performances. A scene in particular towards the end of the film, where Schindler breaks down considering how many more lives he could have saved, is profoundly moving and remains etched in my mind as one of the more powerful, heart rendering scenes in Cinema. That the film was shot in black and white, with rare, occasional use of colour to symbolise or highlight an element of importance, heightens the experience. Easily, Spielberg’s best film, it remains an essential movie viewing experience.

43. Lawrence Of Arabia (1962)

Cinema as a medium keeps getting grander. With cutting-edge technology at their disposal, today’s filmmakers offer us some visceral cinematic experiences. But there are some films made before CGI was in the vogue, whose sheer and monumental scale have not found a peer. David Lean’s epic historical drama based on the life of T. E. Lawrence, one of Britain’s most renowned figures, is one such film. It stars Pater O’Toole as Lawrence and chronicles his adventures in the Arab Peninsula during WWI. Right from the get-go, David Lean paints a resplendent moving picture of the infinite desert in all its glory, aided by cinematographer Freddie Young and a gripping score by Maurice Jarre. But it in no way sacrifices emotion for extravagance. At its heart, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ is a stunning character study of Lawrence – his emotional struggles with the personal violence inherent in war, his own identity, and his divided allegiance between his native Britain and its army and his new-found comrades within the Arabian desert tribes. This wholesome quality makes ‘Lawrence Of Arabia’ one of the most influential films ever to exist.

42. The Searchers (1956)

Arguably the greatest western ever made, the finest film of John Ford’s great career, ‘The Searchers’ is an American classic, among the finest films to emerge from the fifties. Though admired and respected at the time, its lacerating, staggering power was not recognized for a few years, but by the early seventies, it was hailed as a classic of the genre and perhaps the finest western ever made. Certainly time has eroded some of the film’s power, but not that towering, raging performance from Wayne, nor the racism within the film which fuels the anger and rage. The driving narrative of the film, Ethan and his search is timeless, as powerful today as it was back then, perhaps more so because so many of the subtle story points are now clear.

41. Pather Panchali (1955)

The film that brought forth Indian cinema to the world and gave cinema one of the best auteurs, Satyajit Ray. Based on the novel of Bibhutibhusan Bandopadhay, ‘Pather Panchali’ tells the story of an impoverished family, trying to thrive through many adversities of life. One can argue that it romanticizes poverty, as the viewer witnesses the many ordeals that family faces, earning their livelihoods. Despite of that, it’s the moments, interspersed with the maestro Ravi Shankar’s music that stays with the viewer. The affectionate relationship between Appu and her sister Durga, the train sequence, which is one of the highlights of the movie, takes the movie to a different level altogether. ‘Pather Panchali’ over the years has become one of the cult movies and features regularly in the lists of greatest movies of all times, and deservedly so.

40. Casablanca (1942)

The quintessential American classic film. There is perhaps something so infectious about its charm that you still fall in love with it, even all these years hence. Apart from its immense re-watchability factor, its memorable score (As Time Goes By!) and supremely quotable dialogue make for a strong case. Simply put, it’s a treat when all the elements of a great cinematic experience are present in just the right amounts!

The storyline is simple to say the least, almost bordering on banal at times. A cynical, heartbroken man who runs the most famous nightclub in Casablanca finds himself at crossroads when the lady he loved shows up with her husband. The plot devices here are the famed letters of transit, but the story is squarely about the two lovers set against the backdrop of the early stages of the Second World War, and the tough decision faced by Bogart’s character, of hanging on or letting go. However, as with many movies of this genre, the execution does the trick, transforming ‘Casablanca’ into one of the most compelling romantic dramas of all time that is also incredibly well acted; Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman are top notch, and are ably supported by players like Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, and Conrad Veidt.

39. Barry Lyndon (1975)

When looking at cinema as an artform, there’s no denying Barry Lyndon’s perfection, from beautiful cinematography, mesmerizing set pieces, outstanding music to powerful direction. As a story, it talks about the life of a young man in 18th century Europe as he climbs the steps towards aristocracy, only to be led back down by his ill-fate. The picture has within itself some of the greatest scenes ever filmed, making jaw-dropping uses of light, colors, physical features, etc. There’s no better way to summarize the life of a person than to look at it objectively, and that is what this film has done using an unreliable narrator. It is cold and distant, rarely giving the audience a chance to feel for the protagonist. From this perspective, Barry Lyndon is a lavish character study, with rich characters, a realistic touch, and a poetic way of communicating emotion. It simply is cinema at its finest.

38. The General

One of the oldest titles on the list, ‘The General’ serves as a reminder that many a modern action masterwork are sitting in a very long shadow- cast by none other than the silent comedy genius Buster Keaton. Boasting an oeuvre as impressive as even Charlie Chaplin, the latter artist’s lovable tramp trades places with a cavalcade of delightfully goofy characters in Keaton’s case; all surrounded by bristling cinematic inquisivity that stretched the boundaries of the medium in flicks like Sherlock Jr. and The Cameraman. All this without even mentioning his magnum opus, 1927’s The General: Following a Confederate engineer rushing to warn his side of the advancing Union troops during the American Civil War. Its narrative forms a template for George Miller’s recent ‘Mad Max: Fury Road’ and pretty much every cat-and-mouse film ever made, enduring with its hilarious comedy, impressive special effects and bravado stuntwork that sees Keaton put his life in danger more than once all for the adulation of his loving audiences. The General remains one of, if not the, finest action film ever made- one that has fun with every ounce of its being and manages to summon as many superbly handled moments of epic scale to rival any CG-laden romp made today.

37. Blow Up (1966)

The time ? The swinging sixties. The Place? London. The city that dazzles and razzles. Vibrant and glamorous. Sex, drugs and rock n roll. All in all, a day in the life of Thomas, a fashion photographer living a life of, well let’s say dubious morality. In a day full of events, while going through the photographs of a couple that he captured rather surreptitiously in a park, he discovers a dead body in it. He goes to the same place and finds the body to be the man from the couple. Afraid, he comes back to his studio to find it ransacked but with one photo left, that of the dead body. The next day, the body vanishes. Who murdered him? And why the body vanished? Why Thomas felt that he is being followed? ‘Blow Up’ is director Michelangelo Antonioni’s class act that has inspired many filmmakers over the years including Brian De Palma and Francis Ford Coppola.

36. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2003)

The dizzying, surreal epiphany of love and heartbreak has never been explored in the manner and to the degree of success with which ‘Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind’ does. Lush with beautiful images and inventive score similar to silent-era-esque soundtrack, it’s impossible to explain everything about ‘Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind’. No doubt the film is layered with a difficult to follow narrative — though actually, it’s simple once you start following — it’s one of those films which is richly rewarding simply because you can’t stop yourself from swooning over the highly thoughtful concept and deeply moving film that it is. But the real star of the show is its writer, Charlie Kaufman, who in the form of ‘Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind’, might very well have written the most profoundly brilliant screenplay ever in cinematic history. A film that is not only unique in its own way but also endlessly re-watchable with something new to be found within every viewing.

35. Taxi Driver (1976)

In ‘Taxi Driver’, Martin Scorsese gives us one of the most disturbed, unlikely yet whimsical protagonists of our times in Travis Bickle. The film follows him as he becomes a taxi driver to cope with his insomnia and watches him being slowly overcome by all the madness in the city around him. The real way Taxi Driver wins as a film is how it succeeds in creeping up at you, slowly working its way through the sleaze and horror that seems to affront Travis Bickle. In that, it rightfully earns its distinction as a psychological thriller more than a drama, often working on more levels than simply the two. The film may be a disturbing watch for some, owing to its dark subject matter, an even darker treatment and a handful of violence, but for viewers willing to look past it, it is nothing short of a brilliant attempt at understanding the part of the human psyche that most often stems itself in the form of vigilantism. I mean, who doesn’t muse about rising up to the incorrectness of our times and giving it back? It is that deep-seated wish fulfillment fantasy that ‘Taxi Driver’ toys with in a highly effective manner. The film is now widely regarded as one of the most important films ever made and introduced the world to the force that was Scorsese.

34. Paths Of Glory (1957)

Before Stanley Kubrick marched on to explore the inexplicable aspects of society that not only transcended time, but also the viewers’ expectations from their own selves, he made this riveting war piece which I rank alongside ‘Come and See’. Unlike the latter, Paths of Glory extracts its heartbreaking rendition of WW from the same shallowness of humanity, that dominated Kubrick’s latter works. In Kubrick’s world, the demons aren’t covered in blood and mud, but with medals and pride, and hell delves in the most sacred of places, the court. At a time when the industry had adopted the attractive 3 strip, Kubrick’s monochrome painted the war with a single shade. The bodies, the rags, the barracks, the smoke, the ash, everything camouflaged with the common sight of distressing agony.

33. Three Colours: Red (1994)

The saddest part of an artist’s demise is when you think that their final work happens to be their greatest ever. This was the case with Polish auteur Krzysztof Kieslowski and his last film ‘Red’. Kieslowski had already announced his retirement from filmmaking after the film’s premiere at Cannes in 1994 but it’s his tragic demise almost two years after he announced his retirement that makes it even more profoundly sad. ‘Red’ is the final installment in his highly acclaimed ‘Three Colours’ trilogy and is about a young woman who comes across an old man after she accidentally hits his dog with her car. The old man is a retired judge, detached from life and any kind of emotions and spends his time spying on other people. An unlikely bond with subtle romantic undertones develops between the two. ‘Red’ is about chances and coincidences that strike us everyday and our failure to recognize the beauty and significance of it. There’s an inexplicable sense of melancholy that runs throughout the film about the tragedy of human destiny and time and how we as people in the world are all connected in some way or the other. ‘Red’ is an astonishing feat in filmmaking and is simply one of the greatest films ever made.

32. The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948)

As the name suggests, we often associate treasure hunts with the pulsating adventure and the adrenaline rush associated with it. But very few stories are there which speak about the emotions that people undergo while embarking on a journey to get that gold. It’s often said that adversity brings out your true character. ‘The Treasure Of Sierra Madre’ tells a story where the lust for the gold brings unsavoury changes in the characters, ultimately resulting in their individual desolation. While the focus is on the greed corrupting the conscience, it’s the study of human character under adverse situations that stays with the viewer. A tragic tale of greed and betrayal, this movie won the academy award for best director, best-adapted screenplay and best supporting actor. Over years, this has become a cult classic for cine lovers around the globe.

31. Pulp Fiction (1994)

Pulp fiction, a term which is denoted to the magazines or books highlighting over the top violence, sex and crime. These elements made the magazines sell like hot pancakes. Tarantino took these elements, blended them around three stories and created a narrative that was no less than a cinematic genius. One of the most unique pop culture movies to have been made, the viewer gets introduced to the world of mob hitman Vincent Vega, his partner in crime and motormouth Jules Winnfield, the gangster’s wife Mia Wallace, the boxer Butch Coolidge and gets blown away with its stylish treatment of crime and violence. One of the most important aspect of the film which contributed to its success was Samuel L Jackson’s performance. As the hitman Jules Winnfield who quotes bible verses as punchlines, he was phenomenal. One of the greatest films of this era, ‘Pulp Fiction’ has become a textbook for aspiring filmmakers worldwide.

30. The Battle of Algiers (1966)

Few films have wielded the burden of politics in a way that enriches their cinematic effect, but leave it to slick-named incendiary Italian maestro Gillo Pontecorvo to take the still simmering flashpoint of late 50s French Colonial oppression of the Algerian people and turn it into something utterly compelling. The still-prescient parallels Pontecorvo’s admirably neutral observation of terror and terrorism committed by both sides draws today makes experiencing ‘The Battle of Algiers’ a fascinating intellectual challenge to our understanding of black-and-white warfare, a-la the impaling coldness of Miklós Jancsó’s indelible filmography. Moreover, its newsreel editing techniques are a landmark in filmic communication and in my mind made far stronger use of the Nouvelle Vague’s frantic cutting techniques than many of its explorative mastheads. Once seen, never forgotten- ‘The Battle of Algiers’ is quite simply a seminal piece of world cinema.

29. Goodfellas (1990)

It is a director’s dream to create an film epochal to the period it is made in. But for Martin Scorsese, it is a habit. For every decade he has been an A-Lister, he has made a film considered to be amongst the greatest of the period. He made ‘Taxi Driver’ in the 1970s, ‘Raging Bull’ in the 1980s, ‘Goodfellas’ in the 1990s, ‘The Departed’ in the 2000s and ‘The Wolf Of Wall Street’ in the 2010s. And it is the 1990 gangster drama based on the true story of mobster associate Henry Hill which became one of the benchmarks in the genre. The film, narrated in the first person by Hill, chronicles his rise and fall as a part of New York’s mafia from 1955 to 1980. In contrast to all the gangster extravagance in ‘Godfather’ or ‘Scarface’, ‘Goodfellas’ deals with the authentic minutiae of daily gangster life, laying focus on as much focus on Hill’s relationship with his wife Karen as his exploits with his gang mates. But Scorsese uses all the arrows in his quiver of tricks to make this affair enticing, like this legendary long tracking shot, some memorable dialogue and an explosive act by Joe Pesci as Tommy DeVito, Hill’s tempestuous associate. When it comes to the crime genre, ‘Goodfellas’ is as good as it gets.

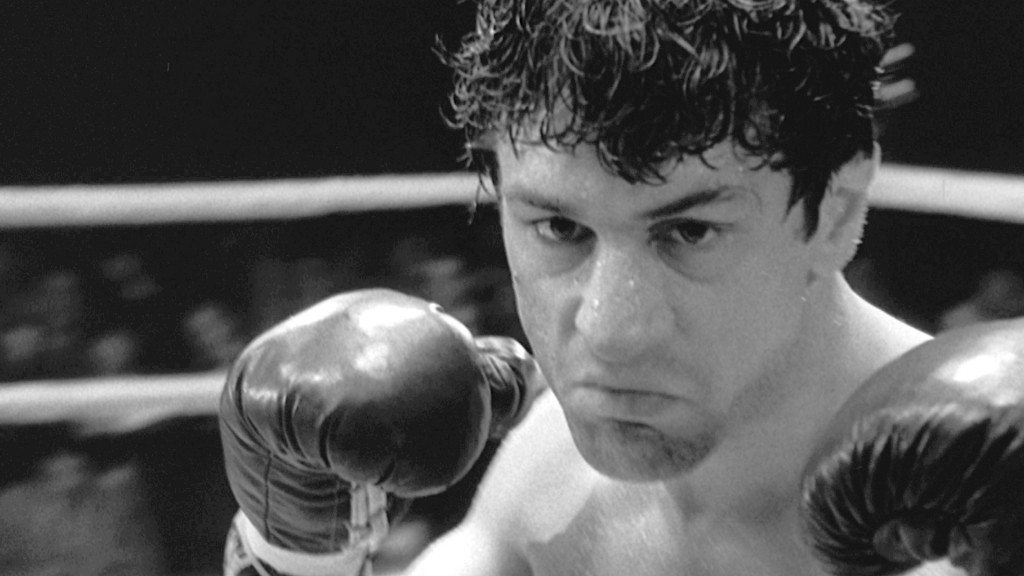

28. Raging Bull (1980)

Martin Scorsese is known for depicting stories of broken, flawed, often self-destructive protagonists in his films. And he has often scoured the annals of history to find his fallen heroes in true stories. ‘Raging Bull’ is the life story of legendary boxer Jake LaMotta, whose self-destructive and obsessive rage, sexual jealousy, and animalistic appetite, which had made him a champion in the ring, destroyed his relationship with his wife and family. The film is entirely shot in black-and-white, to veritably portray the the era it was set in and the dark, depressing mood it defined. Scorsese expected that this was going to be his final project. Thus, he was painstakingly exacting in his filmmaking. Equally dedicated was Robert De Niro, who stars in the titular role. He gained 60 pounds and actually trained as a boxer. He imbibes the short-fused mannerisms of LaMotta with fiery perfection as he completely submerges himself into character. He received a deserved for his troubles. This is Scorsese-De Niro’s biggest triumph. An intense, powerful magnum opus.

27. The Godfather: Part II (1974)