While a very different kind of cinema feverishly grips the globe, it would do us well if we periodically come back to a parallel kind of cinema as suggested by my editor, as a refuge or as therapy or just by matter of choice. Parallel or Indie or even Arthouse cinema aside, if you consider yourself a cinephile and that you may have seen “everything”, I advise you to watch ‘Dogtooth’, or as it is originally known, ‘Kynodontas’ in Greek, after that. If there would be certain films capable of changing your “everything”, I believe ‘Dogtooth’ to be among them.

You probably would have already heard about the Greek auteur Yorgos Lanthimos following his successful stint at the 2019 Oscars with ‘The Favourite’, and his other films that made an impact on western audiences, chief among them being ‘The Lobster’ and ‘The Killing of a Sacred Deer’. While having seen a fair share of this impactful director’s works, I am yet to form an informed opinion on his directorial style still, but I’ll give you that his films are unlike anything that you may have watched. To term them weird or eccentric would be simplifying and even vilifying them beyond belief and sense. The same would be the case with his 2009 Oscar nominated feature ‘Dogtooth’.

Well, I will reserve saying what I felt while watching ‘Dogtooth’ and the kind of diverse things it made me feel till the end of the article, I can say this: ‘Dogtooth’ will take you back to the days when he was truly unbound, and independent as a filmmaker, and might I add, still exploring and experimenting, as opposed to now when he is a filmmaker more confident and grounded in his craft and selling exactly that.

Unassumingly going over the internet, I came across a particular piece claiming that arthouse cinema was meant to inspire dialogue and conversation. Even the message-giving, sermonising or case studies in philosophies are reserved for a different tier in commercial cinema. I may not have fully agreed with that, now that I perceive every single indie flick I have seen, Hollywood or not, it does become an interesting lens for me to spot and carefully classify one.

The same lens also proves useful when you look at the case in point: ‘Dogtooth’ doesn’t have a definite start and doesn’t have an inspiring end, or an end at all. It just cuts, leaving you to wonder what fate awaited the characters you just spent 90 minutes with. It doesn’t have a single character that is likeable or even relatable, even if you might grow slightly empathetic of one of the kids, especially the elder daughter. Yet still, ‘Dogtooth’ manages to get to you and stay: its idyllic setting seldom unsettling as its residents, and the utopia created too false to sustain longer than it did in the film. Without going any further, we jump straight to a brief summary of the plot followed by an examination of its pressing themes that it chooses to convey to subtly. Read on.

The Weird Family

‘Dogtooth’ primarily involves five unnamed characters residing in a fenced compound, a beautiful country home, in an unnamed city in an unnamed country. The parents have raised the three children: two daughters and a son, in confinement at the estate for perceivable cynicism of the outside world and its influences, strictly under their control.

The film begins with the siblings listening to recordings of their mother stating incorrect meaning of words, in an effort to condition them to life inside the estate and keeping them willfully ignorant of the world outside. For instance, the sea is told to them as being a leather chair with wooden arms, motorway is a very strong wind, an excursion is a very strong material used to construct floors, and a carbine is a beautiful white bird. You immediately get the sense starting with the film that something is seriously wrong with the seemingly idyllic households the three siblings don’t seem to question any of it, and you realize that everything that could mean anything to the outside world, or to the very concept or notion of freedom has been tampered with to give it a new meaning, one that nobody was allowed to question.

As later revealed in the film, the children have been instructed to be ready to leave from the estate when their dogtooth (canine) fell, and that the only way to get safely out was a car, much like their father who went out every day for work. The parents have also constructed a lie wherein they have a second son, a fourth child who they have ostracised from the family as a corrective measure for him, meant to keep the other three in check. The family is regularly seen throwing things on the other side of the fence, and the son even talking to the fence in an attempt to get to him, even if naively so.

The Routine

While inside the estate, the children spend time mostly egaging in “endurance games”, like in the beginning of the film wherein they each keep a finger in hot water, and the last one to pull out wins, and “training”, with any of the supposed vices that lure regular children of their age completely absent, including anything that could introduce them to pop culture, films, songs, and even books. The only music they listen to is their own and the only film they watch are home videos they shoot themselves, chosen as a form of entertainment by the one out of the three who scored the highest number of stickers, rewarded for compliance as opposed to violence in exchange for infractions. They routinely physically workout and swim in the pool on the estate on a carefully constructed regimen and are in top physical shape. That is where I close with the description of the day-to-days of this family that seems to put a new twist on the word dysfunctional.

Sexual Deviants

If you thought what you have read until here or seen until this point was weird in the actual sense of the word, you are in for a ton of surprises, and shocks. The first one perhaps comes in within a few minutes of the film’s opening when we see the father driving home one of his factory’s security guards, Christina (the only recurring character with a name) in blindfolds to have sex with his son. This is presumably to satisfy the bodily urges of the son and keep them in check, and the father even pays her for the same. Little did the man knew that she would prove to be the very catalyst in breaking the perfect equilibrium he had created for the family.

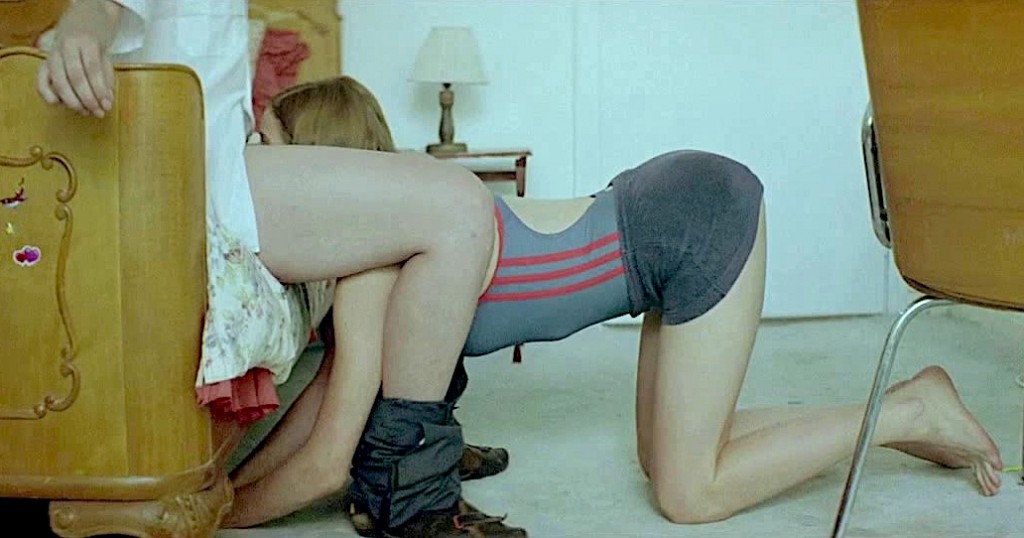

During one of their sessions, Christina demands cunnilungus from the son to pleasure herself, only to be blankly refused by him, the latter seemingly unaware of sexual activity as an indulgence more than sheer necessity. Christina frustratingly asks the elder daughter for the same and barters her headband that she claims “glows in the dark”, and the daughter obliges.

In an increasingly uncomfortable scene later, we see sexual tension mounting in the household as the elder daughter asks the younger to lick her shoulder in exchange for the band. The younger does it later again, regardless, without seeking anything in exchange, perhaps as a way of exploring pleasure seeking for both, but all of it happens in a very direct fashion, with nothing held back and no reservations or hesitations among either, a plausible result of their naivety and lack of exposure, hence a hampered sense of judgment of right and wrong, and everything in between. I also suspect it to be a common activity within the household as we later see the youngest lick her dad towards the ending as well.

The Cat

A stray cat unassumingly finds herself on the grounds of the estate, where the children are terrified of seeing it, and the son proceeds to kill it with a pair of pruning shears. The parents use this to their advantage by claiming that the cat was a vicious creature indeed, the most dangerous one from the outside world, and that their yet unseen brother was killed by the cat, after their father tears off his clothes and covers himself in fake blood, convincing them of the fake attack by the cat. The family then holds a funeral inside the property for their brother on the other side of the fence, and the father teaches the family to howl on all fours (like a dog) to hold their own against cats. A new, wry and yet uncomfortable kind of humour stems from the situation, something that is aplenty in this film.

Losing Control

Christina later tries to barter with the elder daughter again for “licking her” in exchange for hair gel, but the daughter refuses demanding something better. Christina hesitatingly hands over two Hollywood film DVDs to her and promises to retrieve them within a week. The elder watches the films at their VCR player in the night, and tries to recreate iconic scenes from one of the ‘Rocky’ films, and even quotes dialogues verbatim. The father finds out and after beating the elder for her infraction with the VCR tape, he even hits Christina at her apartment with her VCR player, cursing her future kids to have bad influences and a bad personality as punishment for the evil she had brought upon her family.

In the absence of Christina, and increased instances of the parents realising that they were losing control, they have the son choose one of the daughters by blindly fondling them in a bathtub to satisfy his urges. Him and the elder one later have sex, and while the latter is increasingly uncomfortable about it, she quotes a dialogue from the ‘Rocky’ film to threaten him.

Later, as the family gets together to celebrate the parents’ anniversary, the trio of siblings perform as the couple watches. While the son plays a feisty tune on the guitar and the younger daughter excuses herself to rest, the elder continues dancing, almost as in an act of defiance, to the moves of ‘Flashdance’, an 80s Hollywood pop cultural phenomenon, much to the chagrin of her parents. Later that night, she knocks off her dogtooth with a small dumbbell, and bloodied, hides in the boot of her father’s car. The bloodied mess left behind by her is discovered by the father who searches for her inside and outside the house, all in vain, as the rest of the family gets on all fours and starts howling, probably in an attempt to fend off any cat attacks, just in case. The father drives to his factory in the same car the next day, and the screen cuts to credits just as the camera pans at the unattended boot of the car long enough.

The Ending, Explained

I am going to devote this entire section to the development of the arc of the elder one, since after all she is the one to have escaped that captivity and has the final shot focussed on her inside the trunk. Well, there are no two ways about it, the ending was as open ended as you’d like it to be, and as unilateral as you want it to be. It is abundantly clear that the elder one eloped and hid in the trunk her father’s car, realising the falsity of the idyllic household and perfect family that their parents were creating, having a sort of awakening after watching the Hollywood films she bartered from Christina, something that her parents considered bad influence. Her discovering that the telephone was not a salt cellar was part of her awakening.

Now, as the film closes, one could reasonably assume that she would still be hiding in the trunk, and would escape into the world outside the first chance she gets. If not, any of the other million possibilities only Lanthimos is capable of brewing. However, as stated in the introductory paragraph, that is far from the point of it. What it intends to do is give you enough to feed a discussion or an open dialogue, and that it does. The film ends even as you grow curious about the fate of the elder one, choosing to end with no definite answers, and all of them at once.

From the initial bits in the film, Lanthimos drops in hints on a sort of “rebellion” brewing inside the eldest one: it would almost seem like she was in a way aware of the false utopia her parents were creating. My tentative conclusion stems from the observation when she first threw the toy airplane outside the fence, possibly to urge someone to attempt to get to it, followed by her cutting her brother’s arm with a kitchen knife in what I believe was an act of unchecked rage. Her ‘Flashdance’ was an act of open rebellion in front of her parents, and stripping off her dogtooth both an act of breaking free and an act of mockery against her parents’ almost fascist upbringing.

If I am to term Christina the disruptor of their ‘natural’ equilibrium, it was the elder one who basically enabled her to do it: it was her psyche that appealed to Christina, even if unassumingly. Towards the ending too, through eloping, she basically just blows the lid of the container for the truth to come out: the father in an unsuccessful attempt to search for her walks outside directly, contrary to what the couple taught their kids, as opposed to car being the only way to go out. The two siblings continue howling on the threshold of the house simply excuse they are too brainwashed to see.

Do We Want an Animal or a Friend?

The question in the title of this section is asked by the trainer at the facility where the family’s dog is being trained to become more obedient and docile, immediately establishing a rather unfortunate parallel with the canine and the children he is rearing in a similar fashion.

One of the most unmistakable themes of this complex narrative if you wish to draw from it would be control: the over-application of it or the lack thereof. We are basically dealing with a film that portrays home-schooling at its worst, darkest and most twisted under extremely paranoid parents, who believe anything outside those fences is a corrupting agent. It is almost as if they are running a totalitarian regime within those walls: one where a sense of freedom of expression and of activity was completely absent. It is also akin to George Orwell’s seminal literary work ‘1984’, wherein Newspeak is replaced with a completely new vocabulary: one where a vagina is also a keyboard and a bright white light, thus curtailing whatever little freedom of thought that could’ve prevailed.

Now, the control essentially works in two ways: by keeping them blissfully unaware and misguided about the outside world, the parents have almost crippled the children in terms of surviving in the outside world by making it impossible for them to adapt in ways other than physical. On the other hand, the children too would almost certainly be rejected from an unforgiving world, something that should double up on your perception of the ending. Just goes on to show the impact an upbringing can have.

Nature’s Equilibrium

Moving away from the obvious themes, I strongly believe Entropy to be another one. In nature too, any equilibrium may not last long by virtue of it slowly moving towards disorder, and entropy is a measure of that. That would imply that no matter how hard the parents would have tried or however hardly control was asserted, a similar outcome would rather be imperative by the end of it. The means could be any: here it was Christina, even if unknowingly, while some of it was internal as well. The violence in the scenes wherein the older one cuts the son’s arm, or the younger one hammers his knee and blames it on the cat, the sisters inhaling anaesthesia as an endurance game etc are all outlets opened up as a response to excessive smothering. Come to think of it, something similar occurs in ‘regular’ kids when they indulge in fights or substance abuse, especially when the parent or overseer is excessively restraining.

The film also reeks of a regressive patriarchal setup within the household where the son’s sexual needs are taken care of even if the sisters have to be offered up for that, while there is barely any mention of the need to do the same for the daughters. Among so many issues, it would seem rather befitting that the aeroplane flying over their heads becomes a metaphor of irony. “I’ll have it when it falls!”, she says. “The one who deserves it will have it”, her mother retorts.

Final Word

Yorgos Lanthimos’ tale of a perceived utopia and its shortcomings and eventual falling off is an effective, albeit an eerily scary one. For some around the globe, it may even hit closer home, where abuse and control is all but a part of the upbringing. It is almost as if the estate where the five reside is on a different planet altogether, it is that isolated, even geographically it would seem. This is perhaps why Lanthimos refrains from disclosing any names, be it the setting, or the names of the members of the household. The film, in my opinion is a carefully mounted study of interpersonal relationships under confines, and how they proliferate despite. It is bleak, even spiteful in parts, and will test you. If you haven’t ventured into Lanthimos’ filmography, ‘Dogtooth’ may be the best place to start, since it essentially embodies the full Lanthimos experience. For the love of indies, don’t miss this one.

Read More in Explainers: The Lobster | Hellboy | Requiem for a Dream

You must be logged in to post a comment.