Created and directed by Oscar-winning filmmaker Steve McQueen (‘12 Years a Slave’), ‘Small Axe’ is a film anthology series that was broadcast on BBC in the UK before it received a US release on Amazon Prime Video. It depicts the black experience in Britain through the perspective of the Windrush Generation, the Caribbean people who immigrated between 1948 and 1970. McQueen, being of part Grenadian and part Trinidadian descent, was a child of two individuals who belonged to this group and witnessed first hand their trials and tribulations.

The first film of the film series, ‘Mangrove’, tells the story of the eponymous restaurant in Notting Hill and the brilliant group of artists, intellectuals, and activists it brings together every night. After constant police harassment, the owner, Frank Crichlow (Shaun Parkes), and his patrons organize a march towards a police station. However, they are then arrested and tried. If you are wondering whether it is based on a true story, here is everything we know.

Is Small Axe: Mangrove Based on a True Story?

Yes, ‘Small Axe: Mangrove’ is based on a true story. McQueen based the screenplay, which he co-wrote with Alastair Siddons, on the celebrated Mangrove Nine trial, which lasted for 55 days in 1971. Crichlow set up his restaurant in 1968 at 8 All Saints Road, Notting Hill. This Notting Hill was significantly different from where Hugh Grant and Julia Roberts romanced each other for the eponymous film.

In 1962, the Westway Motorway was built, which led to the availability of apartments with low rents in the locality. Immigrants, mostly from the Caribbean, moved into these housing complexes. Crichlow’s business catered to these people. In time, the Caribbean restaurant transformed into a cultural hub that boasted the likes of Nina Simone, Vanessa Redgrave, Diana Ross, and Jimi Hendrix as its patrons. Bob Marley, who took part in soccer games in the neighborhood, often came and spent time in the Mangrove.

As Darcus Howe (Malachi Kirby) beautifully puts during his closing statement in the film, “… wherever a community is born, it creates institutions that it needs. Frank Crichlow, he wasn’t conscious of the fact he was forming a community restaurant. But that sense of community, born out of the struggle in Notting Hill, was so profound that there was no other way for it to be but a community restaurant. We created the Mangrove. We shaped it. We formed it to satisfy our needs. Mangrove is ours. It’s ours! It’s not Frank’s! He lost it to the community. He knows that.”

With the Mangrove’s growing popularity, both the restaurant and its owner came in the crosshairs of the local police department, who considered the Mangrove to be a hotspot for black radicalism. On the pretext of bogus drug searches, the Notting Hill police conducted as many as 12 raids in the span of 18 months. Blue-collar immigrants tend to receive unfair treatment in western countries. Seeing a black business thrive must have jarred these Metropolitan police officers out of their colonial fever dream.

Crichlow wanted to fight this gross example of institutionalized racism through legal and bureaucratic methods, but Howe and others argued for a more assertive approach. The British wing of the Black Panthers was already part of the growing contention through Altheia Jones-LeCointe (Letitia Wright), one of the contemporary leaders of the organization. It all culminated in August 1970 when 150 protestors marched towards the Notting Hill police station.

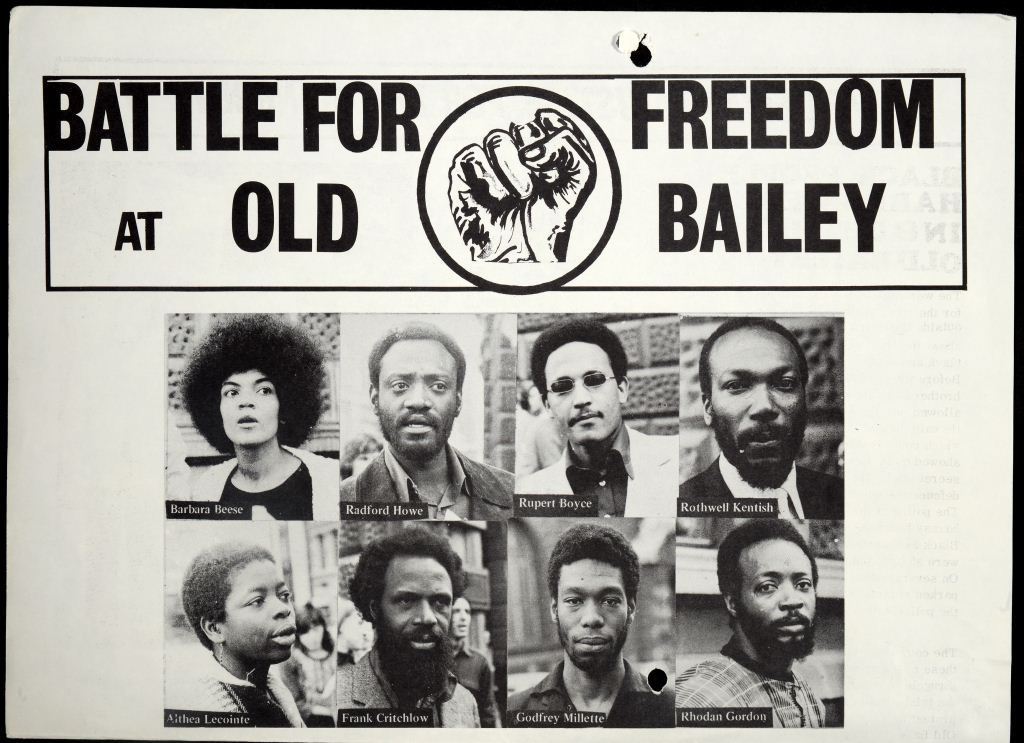

It was initially a peaceful protest but descended into utter pandemonium and violence when several hundred police officers showed up. Nine people, including Crichlow, Howe, and Jones-LeCointe were arrested. The rest were Barbara Beese (Rochenda Sandall), Rupert Boyce (Duane Facey-Peason), Rhodan Gordon (Nathaniel Martello-White), Anthony Innis (Darren Braithwaite), Rothwell Kentish (Richie Campbell), and Godfrey Millett (Jumayn Hunter).

The Mangrove restaurant was established by Frank Crichlow a migrant from Trinidad in the late 1960s. His restaurant became famous for its food and as a centre of Caribbean culture in Britain. (1/3) #SmallAxe pic.twitter.com/443aYv9poT

— Black British Archives (@blackbritisharc) November 15, 2020

Among the charges they faced was that they conspired to incite a riot. The trial drew both media and public attention and concluded after all the defendants were acquitted of the main charges. Crichlow, Howe, and three others were cleared of all charges. But, as the film indicates, Crichlow’s fight against the British establishment didn’t stop. In 1979, he faced charges regarding drug offenses, which were later withdrawn.

The police raided the Mangrove in 1988 with sledgehammers, and he was once again charged with drug offenses. The case was again thrown out of the court, and this time, he acquired £50,000 in damages. But throughout the years of this ordeal, he never received an apology from the authorities. The Mangrove was ultimately closed for good in 1992.

Read More: Small Axe Mangrove Ending, Explained

You must be logged in to post a comment.