Ginny Mohler and Lydia Dean Pilcher’s joint directorial venture, ‘Radium Girls’, is a film about female factory workers in the 1920s standing up against their employers in a fight for workplace safety and health accountability. The movie revolves around sisters Bessie and Josephine, who work together as watch dial painters in an American Radium factory. Set in 1925 in a post-World War I New Jersey, ‘Radium Girls’ tells the story of countless young women and teen girls who, like Bessie and Josephine, took up factory jobs and did their best to land the coveted dial painting positions.

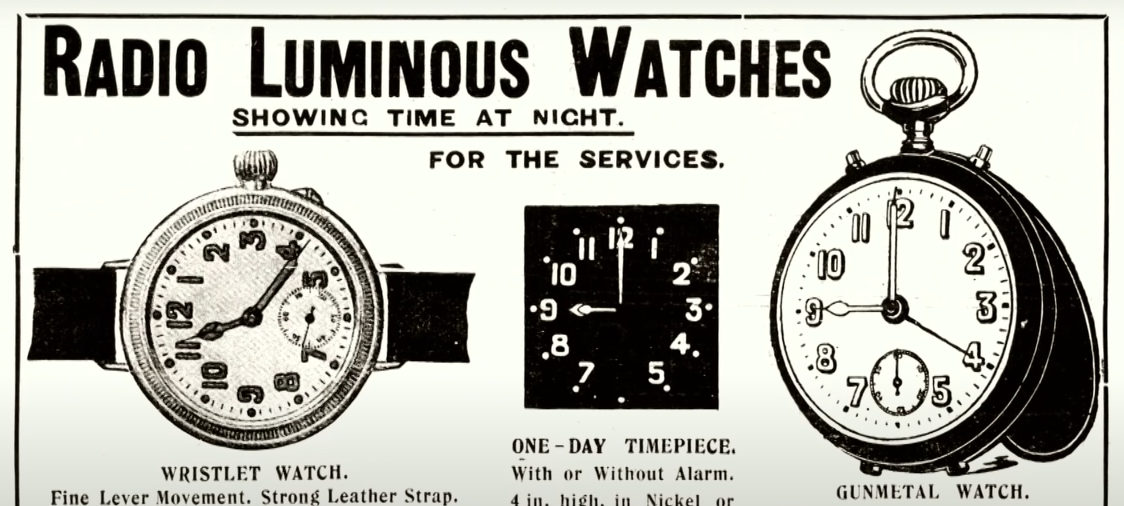

Bessie and Jo are instructed to lick their paintbrushes before dipping them in the pot of radium paint and then painting minuscule numbers on watch dials that will “glow in the dark.” At that time, the newly-discovered radium was considered beneficial for humans when consumed in small quantities. So Bessie and Jo never consider the health repercussions of working in a radium factory and licking radium paint off their brushes several times a day. Until one day, when Jo falls ill with a mysterious disease, the girls never imagine their job might be killing them.

The doctor sent by the factory manager pronounces Jo, “healthy as a horse,” but her falling teeth and aching bones tell the opposite truth. When the company, American Radium, denies all accountability and insists that the girls’ failing health is because of their own bad hygiene, Bessie leads a charge against the powerful corporation in a legal battle that will forever change US labor laws. It’s a finely made film with a powerful message. But is the shocking story of ‘Radium Girls’ rooted in reality? Let’s find out.

Is Radium Girls Based on a True Story?

Yes, ‘Radium Girls’ is based on a true story. Although the characters of Bessie and Jo are fictional, the film’s historical premise and story are inspired by real events. The company shown in the movie, American Radium, stands in for the real firm, United States Radium Corporation (USRC), which had its biggest factory operation in Orange, New Jersey. In 1917, an 18-year-old young woman named Grace Fryer joined the USRC factory as a dial painter. Grace and her colleagues obediently followed the lip-pointing “lick, dip, paint” routine that they had been taught.

Male workers at the radium companies donned lead aprons in their labs and managed the radium with ivory-tipped tongs, never touching it directly. But women were afforded no such protection. The widespread belief that radium was a wonder element, perfectly safe to use, stemmed from research published by the very companies who had built a lucrative industry around it. The factory managers even told the dial painting women that the substance, far from being harmful, would “put roses in their cheeks.”

By 1922, Grace was sick too. The women’s biggest challenge was to prove that their failing health was the direct result of radium handling. It wasn’t until a male factory worker died with the same symptoms that experts carried out proper research. In 1925, Harrison Martland devised tests that proved definitively that radium had poisoned the women. By May 1922, Mollie Maggia (a colleague of Grace Fryer) was literally falling apart due to radium poisoning. Her entire lower jaw was removed, not by operation, but by the horrified dentist reaching in and pulling it out of her mouth.

Mollie was dead by September of the same year. Many of her co-workers followed her to the grave soon, dying of the same strange disease that ate away their insides. Grace led the legal battle of the Radium Girls against the USRC in 1927, but they had to settle out of court because they had only months left to live. But Grace had succeeded in bringing the issue to nationwide notice, which is what she wanted.

The story of the New Jersey Radium Girls sent shockwaves through America, and Catherine Donohue, a dial painter in Illinois, read the news in absolute horror. In the mid-1930s, Catherine and her co-workers took their employers, Radium Dial Company, to court as well. That company went so far as to steal radium-riddled bones of dead factory workers in a callous cover-up. In 1938, Catherine gave her testimony from her deathbed (with the help of their lawyer, Leonard Grossman) in a bedside hearing and ultimately won justice for factory workers everywhere.

Read More: Best True Story Movies on Netflix

You must be logged in to post a comment.