Cinema, at its best, will stay with you for years to come. It gives us the chance to see the world from a different perspective and it connects us like all great art does. Throughout my young life, my perception of this magical medium has changed almost completely. From first watching films as a very young child and simply being blown away by the spectacle and seemingly endless potential of it all to now having reached a point where a great film can change the way I think. To commemorate the power of this world of cinema that I love so much, I have constructed a list of ten films that changed the way I look at movies and, perhaps, life in general.

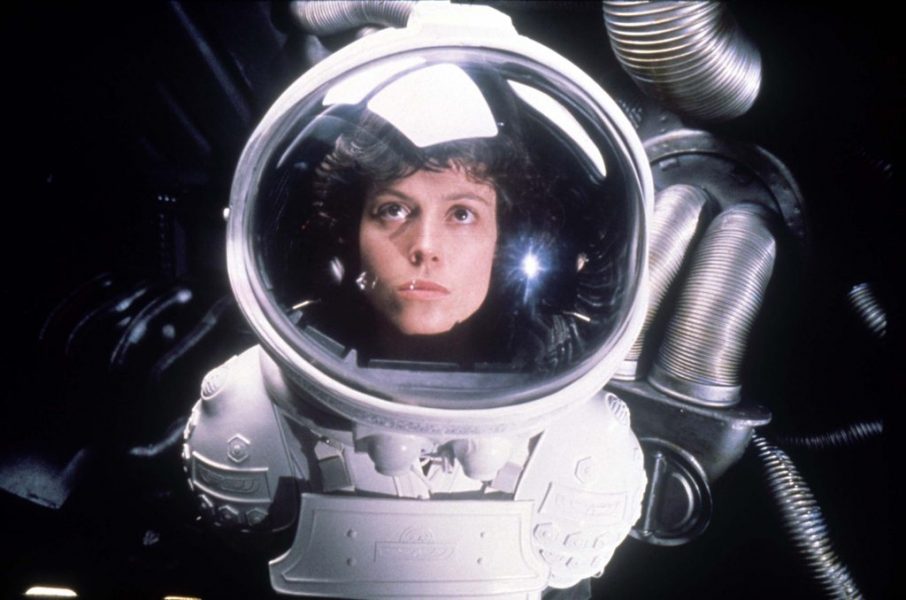

4. Alien (1979)

Fast-forward several years to when I was fourteen (we can skip my awkward Transformers phase) and the real birth of my obsession with cinema. After delving into the excesses of modern blockbusters, I discovered that Ridley Scott offered something more to do with mood and tension. To me this film is about empty corridors, dark vents, water slowly dripping from the ceiling and a real, adult form of terror.

I think it is the best thing Ridley Scott has ever done: I love the tone and suspense, the documentary-like characters, the gorgeous sets, the Jerry Goldsmith score and the way Scott holds it all together. More importantly though, it represents a change in the way I watched movies – or what I wanted to watch. Just like the crew of the Nostromo landing on LV 426, I now wanted to explore cinema and find out if it could frighten me, make me laugh, make me cry, thrill me and make me think.

5. No Country for Old Men (2007)

For a long time, the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men was my favourite film. Not only is it maturely directed, masterfully edited and perfectly shot (by the genius that is Roger Deakins) but it confronted me with themes that I hadn’t come across before. It showed me a harsh world where the bad guy gets away with the money, the good guy dies failing to protect his wife and the law man quits because the world isn’t what is used to be anymore. That is, according to him. According to others, the world has always been this way – he just hadn’t accepted it. I hadn’t seen this world before. The world of Llewelyn Moss, Anton Chigurh and Sherriff Ed Tom Bell tipped what I had come to expect from a thriller entirely on its head. It changed the way I saw the world and it changed the way I saw movies.

6. The Night of the Hunter (1950)

In 2005, Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter was featured on the BFI’s list of films you should see before the age of fourteen. However, I never saw this movie as a child. When I did see The Night of the Hunter, though, I found it had the power to remind me of what it was like to be a child – not in the same way as Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade or other Spielberg films, but instead it reminded me of childhood terrors. To me, this film is a child’s nightmare filmed in the style of German expressionist horror. Robert Mitchum’s performance as the Reverend Harry Powell creates an utterly terrifying creature who manages to keep up with you, no matter how fast or how far you run, at his own steady pace. He’ll find you and when he does you can’t rely on adults to save you – not even your own family. That is the greatest achievement of Charles Laughton’s sole directorial feature: it shows how easily cinema can take you back in time.

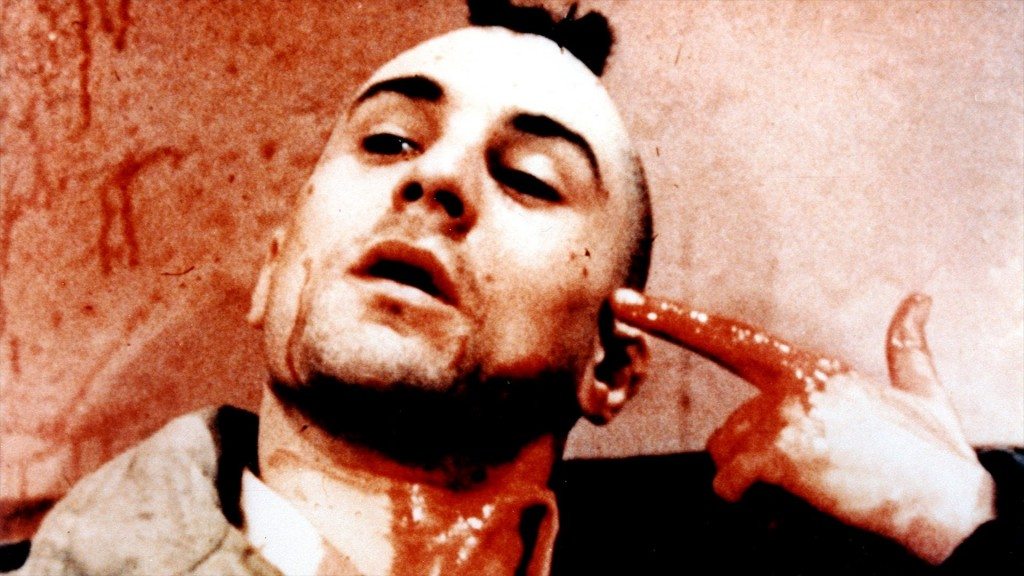

7. Taxi Driver (1976)

I really didn’t get Taxi Driver the first time I saw it – I think I was too young at the time. I knew everyone loved it and that “You talkin’ to me?” was one of the most recognisable movie quotes of all time. It was certainly violent and adult but my expectations were not met. So, I came back a little bit older and a little bit more experienced in life and suddenly I saw it. I saw it all. It spoke on such a profound level – so viciously real and so unrepentantly relatable – that it had gone completely over my head the first time.

Travis Bickle is a veteran suffering from insomnia and living in self-imposed isolation who wanders through the streets of New York like it’s a nightmarish vision of hell. Scorsese’s camera glides through the streets at night, never settling, just like Travis. The trio of Scorsese, Paul Schrader and, of course, Robert De Niro, gave us the opportunity to look at the world through Travis’ eyes. When I first saw the film, this point of view was alien to me. When I came back and saw it again, I felt like it was made just for me. At some point in our lives, we all feel like Travis Bickle. Scorsese knew it, Schrader knew it and De Niro knew it, which is why we have an uncompromising, raw and feverish look at hell by way of New York City.

8. The Third Man (1949)

Bombed-out Vienna streets, shadowy figures lurking in the darkness, light glistening off wet cobblestones, footsteps echoing through the sewers and the sound of Anton Karas playing that iconic zither score – throw in the most beautiful and haunting film noir cinematography of all time, a top notch cast and a brilliant Graham Greene screenplay and you have Carol Reed’s 1949 masterpiece The Third Man, the greatest British film of all time and, perhaps, my very favourite movie.

To not include this on a list of films that changed my perception of cinema would be a crime. This is the gold standard of every aspect of filmmaking coming together perfectly. It’s funny and smart, haunting and dark, heart-warming and bittersweet. We can analyse and break films down all we want to find out why they work so well, but there is a rare, inexplicable magic to cinema that can be found deep in the heart of The Third Man. No matter how hard I try to put that experience in words, it cannot match the sheer joy of sitting in the dark and watching the illusion from beginning to end.

10. Persona (1966)

After Mulholland Drive, the only film to really shake me up has been Ingmar Bergman’s Persona. For the first half an hour or so of its run-time, I thought it was just a lot of talking with some provocative images thrown in there: tarantulas, a crucifixion and the suicide of Thich Quang Duc by self-immolation in Vietnam. I didn’t think there was anything of substance holding it together until I came to the scene where Alma (played magnificently by Bibi Andersson) discusses an orgy she had on the beach. It was then when I realised that the film had snuck up on me. I was completely blown away and caught off guard. It was erotic and disturbing and haunting and utterly, utterly engaging with imagery so powerful I felt I had seen it myself.

My experience of the film after that was completely different – I have never so sharply changed my mind about a film half-way through before or since. I do not know what it means – I doubt I will ever fully make any rational sense out of it, but I don’t think I need to. It provoked a real, guttural response on a level that few films have managed to reach. It solidified the idea in my mind that cinema can be more than just light entertainment – it can be a full, emotional and human experience.

Read More: Best Movies of All Time

You must be logged in to post a comment.