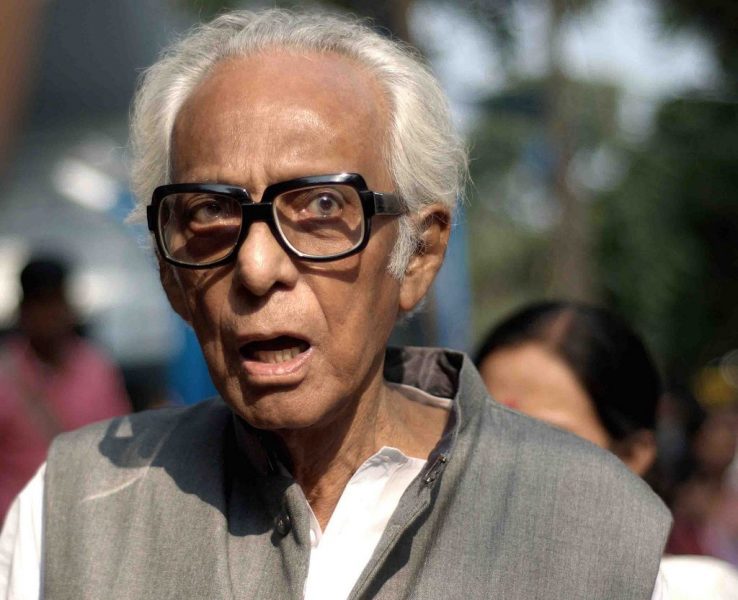

Indian cinema is often equated with Bollywood. The truth couldn’t be any farther. Inane generalizations of such nature usually depict a disdain for objectivity. While bizarre song and dance dramas might have often taken the country’s box office limelight, there have been innumerable reel artists who have worked, often in the dark, to enrich the medium in their own humble ways. In the given context, Satyajit Ray’s contribution is too well known and rather craftily defined. In fact, Ray’s much publicized contributions have repeatedly eclipsed the equally brilliant repertoires of works from many other filmmakers. One such filmmaker who has consistently been kept out of the media focus is Mrinal Sen. It could be emphatically asserted that Sen was the first Indian auteur who successfully blended the political dimension with the social dimension in his cinema. Along with Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, Sen initiated the Indian Parallel Cinema Movement that challenged the hegemony of Bollywood and mainstream commercial cinema.

While Sen is considered to be an out and out Marxist filmmaker with distinct ideological insinuations, the fact remains that the humanitarian aspects of his filmmaking consistently overshadowed his often brazen political aspects. More importantly, he saw the medium of cinema as a brilliant platform to ask questions, to raise issues and finally to arrive at conclusions. Many of his movies intentionally don’t emphasize on the narratives and instead involve the audience in seeking resolutions. This is particularly noteworthy considering the fact that Indian Art Cinema was still at its nascent stage when Sen forayed into the world of filmmaking.

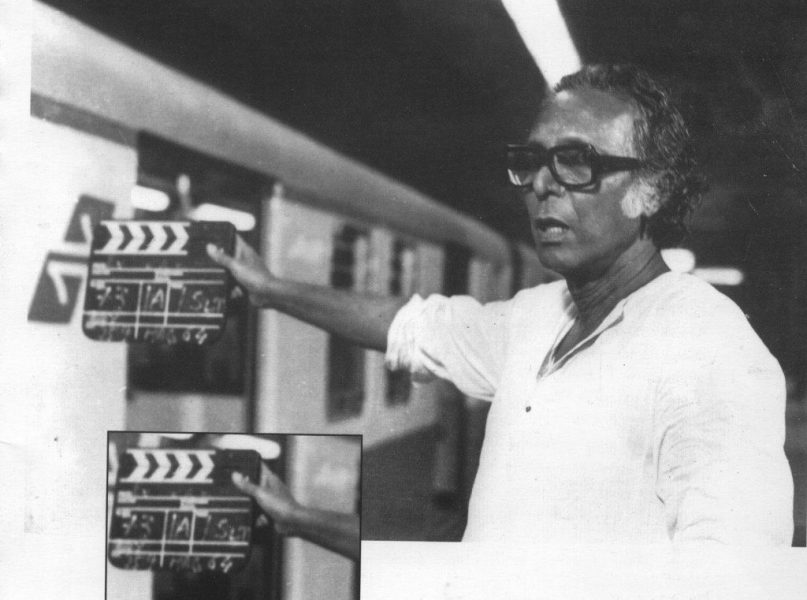

Having started his career as an audio technician at a Kolkata (then Calcutta) studio back during the fifties of the last century, Sen made his first feature film in the year 1955 when ‘Raat Bhore’ (The Dawn) (1955) was released. Interestingly, it coincided with the release of Ray’s seminal piece ‘Pather Panchali’ (Song of the Little Road), the movie that would go on to delineate Indian cinema. Unfortunately, it was both a commercial and critical failure. His next film ‘Neel Akasher Neechey’ (Under the Blue Sky) (1958) was laced with subtle political undertones and marked Sen’s entry into the big league. Sen’s third movie ‘Baishey Sravan’ (Wedding Day) (1960) propelled him to international recognition. However, it was his Hindi language feature film ‘Bhuvan Shome’ (Mr. Bhuvan Shome) (1969) that is said to have pioneered the Indian New Wave of filmmaking. A rather uniquely crafted movie, it featured Utpal Dutt as Mr. Bhuvan Shome and is known for being the screen debut of acclaimed actress Suhasini Muley. Based on a story by renowned Bengali litterateur Banaphool, ‘Bhuvan Shome’ is a definite landmark in the history of Indian cinema. With uncanny humour, a quasi-documentary style and an obliterated and ambiguous character sketch, the movie stands tall as one of the finest creations of new-age filmmaking.

What followed thereafter was a mournful and contemplative tryst with Kolkata and the violent seventies. Before delving into any more details, it is important to understand that Kolkata was going through a transitory turmoil during that time. The ultra-communist Naxalite movement was eating into the city’s core and the hopeless political class was all over the place in managing the widespread frustration amongst the youth. Sen was unapologetic in his approach and lambasted the situation through his much famed Calcutta Trilogy that exposed obvious pitfalls of the then existing system like nothing before. The three films from the trilogy ‘Interview’ (1971), ‘Calcutta 71’ (1972) and ‘Padatik’ (The Guerilla Fighter) (1973) encapsulate the enigma of the youth in a way that is both befitting and humane. It needs to be understood here that there hardly can be a comparison between the two Calcutta Trilogies respectively made by Ray and Sen for the obvious reason that Ray emphasized on the resolutions while Sen was much more open in bringing down the curtains. Also, Sen’s Calcutta Trilogy constituted his way of protesting, an artistic way of shaking the system upside down.

Very few people know that the Bollywood superstar Mithun Chakraborty got his first break through Sen’s immaculately made period drama film ‘Mrigayaa’ (The Royal Hunt) (1976). The movie went on to bag two awards at the 24th National Film Awards – that for the Best Feature Film and the Best Actor. The film masterfully depicts the extent and nature of feudal exploitation during the British Rule in India. Next in line was the Telugu language feature film ‘Oka Oori Katha’ (The Marginal Ones) (1977). Based on a story by legendary Hindi-Urdu litterateur Munshi Premchand, the film is a revelatory tale of rural poverty. It was widely appreciated and was screened across the world.

While poverty and social upheavals have always constituted the prime motivations behind Sen’s movies, he didn’t shy away from the rather sensitive topic of woman emancipation as well. ‘Ek Din Pratidin’ (And Quiet Rolls the Dawn) (1979) undeniably establishes Sen’s feminist credentials. The movie is a haunting tale of deep-rooted patriarchy ingrained in the Indian value system and questions the ethical standings of the viewers. ‘Ek Din Pratidin’ violently shakes traditional morality and compels people to think beyond the confines of their respective comfort zones.

Two of his other notable films include ‘Khandahar’ (The Ruins) (1984), a Hindi language film based on a short story by renowned Bengali author Premendra Mitra and ‘Kharij’ (The Case is Closed) (1982), a unique Bengali feature film that portrays the death of a family child servant and the family’s effort to comfort his grieving father. Some of his later ventures include such masterpieces as ‘Ek Din Achanak’ (Suddenly, One Day) (1989), ‘Mahaprithivi’ (World Within, World Without) (1991) and ‘Antareen’ (The Confined) (1993). The last film from his coffers was ‘Aamaar Bhuvan’ (This, My Land) (2002) that came out in the year 2002. Although Sen is still alive, there is very little probability that he would make any more film during his lifetime.

When Indian celluloid history is rewritten in the near future, Mrinal Sen would be remembered as an uncompromising auteur, someone who never gave in to pointless showmanship and the clamour for publicity. Sen’s movies are suave, revelatory and strong – yet there is an unmistakable aura of humanity about each of those movies that one hardly fails to notice. He might not have been as pristine as Ray was! However he was himself and that was more than enough to imprint a permanent mark on the annals of not just Indian cinema but global cinema as well.

Read More: The 10 Best Movies of Satyajit Ray, Ranked

You must be logged in to post a comment.