It is impossible to gauge the impact that Steven Spielberg’s cinema had on me. Yes, there is Michael Haneke, David Lynch, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Paul Thomas Anderson. But right throughout my process of evolving into a cinephile over the years, Spielberg’s cinema still manages to evoke emotions of pain, hope, joy and adventure in me with pretty much the same effect that it had on me years before venturing out to devour the artistic nuances of cinema well beyond the commercial realm of Hollywood. And I thank heavens for that as his cinema still excites me unlike anything else and my love for his work has not diminished a tiny bit.

Unfeigned love and faith in humanity are innate qualities of his cinema which makes him the most popular filmmaker in the world. But he is not without his detractors. A good number of cynics and scholars have often looked down upon his work, relentlessly thrashing and accusing him of excessively melo-dramatizing and compromising on the intellectual aspects of cinema. Even his most revered films like ‘Schindler’s List’ and ‘Saving Private Ryan’, which were thematic shifts from his previous works deemed as summer blockbusters, have had their fair share of criticism for their perceptibly simplistic depiction of complex issues like war and overly dramatizing the tragic events of the Holocaust for commercial purposes. And 7 years after ‘Saving Private Ryan’, Spielberg returned to the same arena, this time determined to explore the oldest and most complex of political conflicts that baffles the world with its scorching intensity and relentlessness.

‘Munich’ kicks off with some of the most disturbing moments ever captured on celluloid. There is a hitherto unfelt coldness in every scene that Spielberg crafts here with an intensity that is unparalleled in any of his other works. The year is 1972. The greatest sports event has got the world on its feet. At dawn September 5, we see a group of people armed with assault riffles and grenades jumping across the 2 meter fence to the Olympic Village. They seize control of the Israeli athletes’ apartments, killing two and take the remaining hostage. A carnival that represents unity and power painfully bearing witness to the horrific events of human beings, tearing each other apart for reasons drenched in futility and fanaticism. Irony is cruel beyond words. After an explosive opening, the film relents.

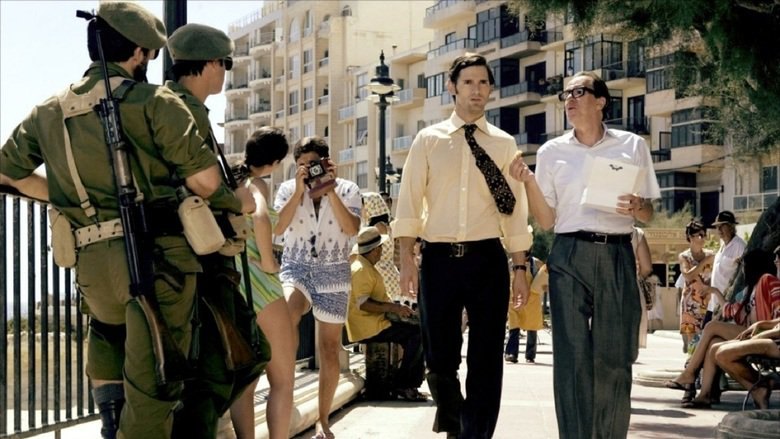

The Munich Massacre has caused a great deal of shock and distress to the world. The families of the athletes couldn’t believe what they were seeing and hearing on Television and news. And this is where the film leisurely takes its time on building the characters and the plot that increasingly gets complex. Avner Kaufman, a Mossad agent, is shouldered with the responsibility of leading a team of Jewish volunteers from around the world to an assassination mission, named “Operation Wrath of God”, against 11 Palestinians allegedly involved in the massacre. Kaufman is a family guy whose wife is pregnant and is desperate to be with her but regards his nation and his own religious identity with utmost reverence and respect and leaves on a mission that would change his life forever. Here we see a man who holds his faith, morality and ethical values in high regards. An untainted soul, naïve in his outlook on the political intricacies and distorted moralities of a government that encompasses his existence but he is only too blinded by the overpowering of congenital idealism over twisted realities.

Rooting for the good-hearted, pure, innocent, quintessential American hero has always been an inherent part of Steven Spielberg’s cinema which makes ‘Munich’ his most exciting and audacious work as he abstains from polishing the raw, impassioned emotions pulsing through the film while also denying his audience with a hero they could root for in the most trying of circumstances. A highly unlikely aspect in a Spielberg film. In many ways, Avner Kaufman is the “hero” we are given and the film is centered around the choices he makes and the questions he asks. His character is depicted as a simple-minded man with an indestructible belief in his country’s moral and ethical values.

Kaufman, eventually transforms into a man whose emotional clutch on faith, loyalty and patriotism slackens over time and with the heightening madness of revenge subjugating the patriotic reflex of defending one’s own nation. His comrades include a South African driver, Belgian Toy maker, a former Israeli soldier and a Danish document forger. Their level of proficiency and expertise have turned them into an unassailable unit as their spate of murders were being retaliated by further murders and more murders, demoralizing the group to the extent of questioning the purpose and rationale behind the murder mission and their very own set of beliefs and morals entrenched in their psyche. The team begins to lose out on each other and their contrasting perspectives on the stormy repercussions of their seemingly futile attempts at restoring peace and justice have culminated in them confronting their own identities muffled by the inevitable moral dilemma the mission poses. There is a scene in the film where a character asks the protagonist, “We’re Jews, Avner. Jews don’t do wrong because our enemies do wrong”, to which he replies, “We can’t afford to be that decent anymore.” Spielberg interestingly questions the value and essentialism of a country’s ethical and moral beliefs whilst factoring in the complications to be dealt with it in modern society when viewed from a bigger picture.

Perhaps, the best moment in the film comes in when our protagonist, masqueraded as the leader of a foreign terrorist group, is smoking outside his room and has an intense conversation with a PLO member about the dispute over their homelands. Through the eyes of an Israeli and Palestinian, Spielberg masterfully crafts a scene that amplifies the voice of an issue too long ignored. Avner says, “You kill Jews and the world feels bad for them…and thinks you animals.”, to which Ali retorts, “Yes. But the world will see how they’ve made us into animals. They’ll start to ask questions about the conditions in our cages.” A thought-provoking statement which encapsulates the paradoxical elements of vengeance and violence. Presenting the film with multifaceted viewpoints could easily be the most challenging aspect while dealing with an issue as contentious and convoluted such as this. Spielberg tries to stay neutral and succeeds to a great extent in doing so.

The film is finely crafted and balanced in its elements of a taut thriller and a fervently poised, intense political drama. The shootout and explosion scenes are shot with breathtaking intensity and nerve-racking tension. There is a scene towards the end of the film where the protagonist makes love to his wife whilst the images of the massacre flash through his mind. It is one of the most deeply disturbing and haunting scenes ever captured on-screen. Avner’s obstinate quest for answers and the aftermath of the unnerving ordeals of his past would perpetually deprive him of a family life he once dreamed of.

‘Munich’ is a deeply disturbing tale of blood and politics; how the two are inseparably entangled in the labyrinth of extremism, megalomania and hypocrisy ingrained in modern society, how the invigorating stench of blood could seduce vengeful human minds. It is, to my mind, Steven Spielberg’s uncrowned masterpiece. One that deserves to be talked about in the same breath as many of the other masterpieces he’s churned out in a long, revered prolific career that shaped and revolutionized mainstream cinema as we know it today.

You must be logged in to post a comment.