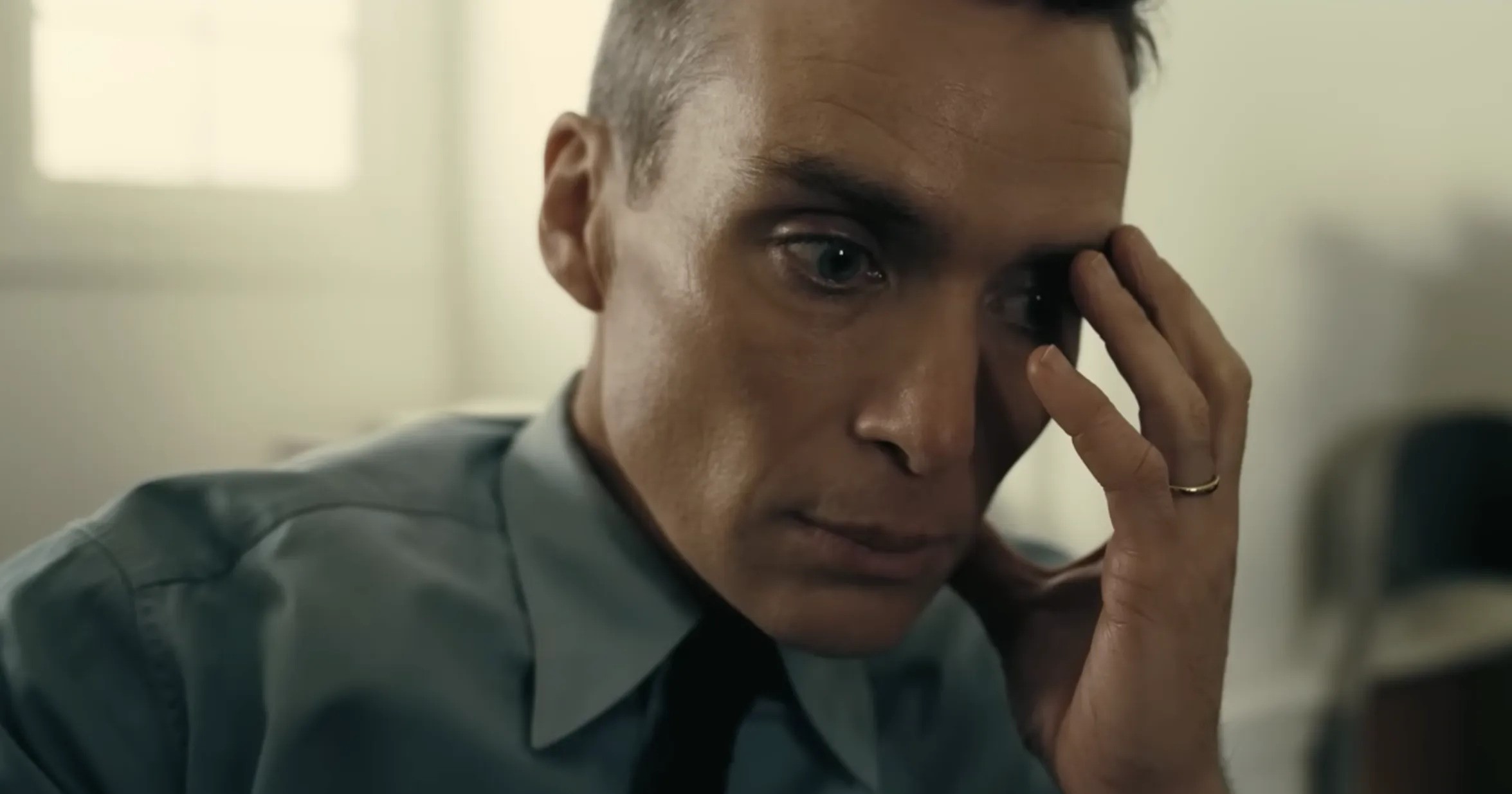

Christopher Nolan’s ‘Oppenheimer’ follows the story of the titular character and his work on the Manhattan Project, which led to the creation of the atomic bomb. Starring Cillian Murphy in the lead role, the film focuses on the challenges Oppenheimer faced during the project while shedding on his personal life and connections. Working on the project required secrecy of the highest level. No one involved in it was allowed to talk to anyone outside of it about what was going on in Los Alamos. However, America’s worse fear came true when it turned out that some people on the project had shared the secrets with Russia. Who were these people, what did they do, and what happened to them? Let’s find out.

Who Were the Spies?

Nolan’s movie focuses on Klaus Fuchs as the spy who unraveled everything. However, over the years, it was revealed that several other people were involved in it in different capacities. There were ones like Harry Gold who served as contact, received information from their sources, and passed it on further. Then there were the scientists who were directly involved with the Manhattan Project. Here’s what you should know about all of them.

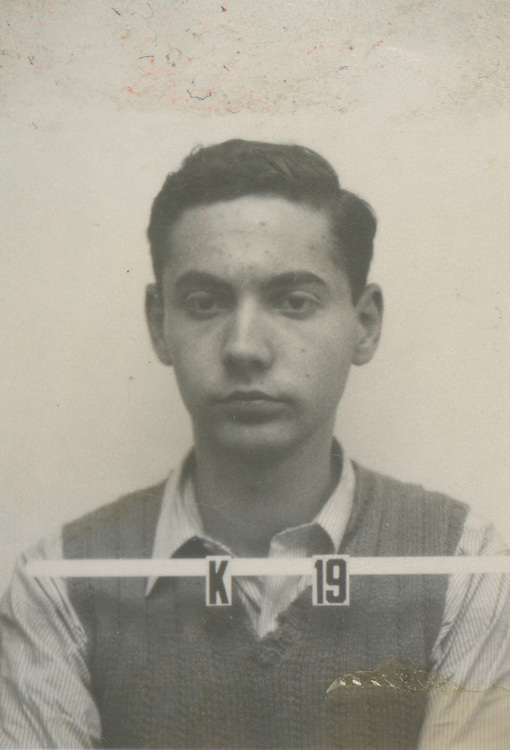

Klaus Fuchs

The German theoretical physicist Klaus Fuchs was the first person whose identity as a spy was revealed through an investigation, which further led to the identification of several other people. Born in 1911 in Rüsselsheim, Fuchs joined the German Communist Party in 1930. He fled Germany in 1933 after the Nazis came to power. He settled in Britain, where he started working as a theoretical physicist at the University of Edinburgh. In 1941, he became a part of the British atomic bomb project called Tube Alloys, which is where he started working as a Soviet agent. In 1942, he signed the Official Secrets Act after becoming a British citizen, but that didn’t stop him from passing over classified information about Britain’s atomic research project to the Soviets.

In 1943, Fuchs was sent to America, where he eventually found his way to Los Alamos to work on the Manhattan Project. He worked on “developing the gaseous diffusion method of uranium enrichment.” His task, under Hans Bethe and Edward Teller, also included calculating the approximate energy yield of an atomic explosion and researching implosion methods. He was also said to have been present at the Trinity test.

In 1944, Fuchs started working with Harry Gold, who also served as a contact with other Soviet spies. Fuchs passed on detailed information about the bomb, which is said to have helped the Soviets develop their own atomic bomb. When the war ended, Fuchs returned to England and worked as the head of the Physics Department at the Harwell Atomic Energy Research Establishment. In 1949, decrypted cables from the Venona project revealed that Fuchs had worked as a spy.

He was arrested in January 1950. He confessed to espionage, was charged with violating the Oficial Secrets Act, and was sentenced to 14 years in prison. He also testified against other spies like Harry Gold, David Greenglass, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. He was released in June 1959 after serving nine years in prison. He moved to Germany, where he died in 1988 at 76.

David Greenglass

David Greenglass came to Los Alamos to work on the Manhattan Project from August 1944 to February 1946. He was a member of the Special Engineer Detachment and worked on the molds for “the high-explosive lenses used to detonate the plutonium core in the implosion bomb.” He was recruited as a spy by his brother-in-law, Julius Rosenberg. Greenglass is said to have passed information about the high-explosive lenses developed for the implosion bomb through a crude sketch and twelve pages of detailed notes.

His identity as a spy was revealed in 1950, following Klaus Fuchs and Harry Gold’s arrest. Greenglass implicated his sister and brother-in-law in his testimony, as a result of which they were sentenced to death and executed in June 1953. Greenglass’s wife is also said to have assisted him in his work as a spy, with them receiving the codenamed KALIBR and OSA. However, Greenglass’s testimony against the Rosenbergs helped him secure immunity for his wife. He was released from prison in 1960. He died aged 92 on July 1, 2014, at a nursing home in New York.

Theodore “Ted” Hall

Ted Hall was a physicist who became the youngest scientist to work on the Manhattan Project. He worked on experiments regarding the implosion-type bomb and “helped determine the critical mass of uranium needed for the gun-type bomb.” Working as a Soviet spy, he passed along detailed information about the Fat Man bomb and the processes used for purifying plutonium.

Receiving the codename MLAD, Hall first became involved with the Communist Party in 1944, where he eventually met Sergey Kurnakov, with whom he passed information from Los Alamos. Following the war, he started working at the University of Chicago and continued his work as a Soviet spy, passing on information about the development of the hydrogen bomb. Eventually, he moved to England, where he stayed till his death from renal cancer in 1999 at 74. The FBI briefly questioned him in 1951, but he was never charged or convicted of espionage.

Oscar Seborer

While the identity of Fuchs, Greenglass, and Hall was found in the years following the war, Oscar Seborer’s work in espionage didn’t come to light until recently. Seborer was an electrical engineer and worked at Los Alamos from 1944 to 1946. He is said to have been involved in devising the bomb’s explosive trigger through the firing circuits of the detonators. This is said to have “reduced the amount of costly fuel needed for atomic bombs.”

Codenamed Godsend, Seborer’s exact work as a spy still remains a mystery, but it’s clear that he was involved with the project in a much higher capacity than all the spies mentioned above. He fled to Russia in 1951 with his family, which included his brother, his brother’s wife, and mother-in-law, and changed his surname to Smith. Reportedly, the brothers confessed that they would be executed for what they did, indicating that their work as a spy might have been the most instrumental in the Soviet Union’s nuclear project. Seborer died on April 23, 2015, in Moscow.

Read More: Was Oppenheimer a Spy? Was He a Communist?

You must be logged in to post a comment.