It’s that time of the year again. No, I’m not talking about Inauguration Day, although its hard not to, but of Nominations Day. On 24th of January, we will know what the Academy, the largely ill-informed, but still somewhat relevant award voting body, will unveil their choices for the best work in the motion pictures of 2016. It will determine what film or contender will not only have a larger potential to reap dividends at the box office, but also remain a longer part of the public’s collective cinematic consciousness. And due to the blinding pizzazz of the Oscars, it sometimes gets difficult to remember or even compel oneself to consume certain works of art that, not infrequently tend to stand taller than the ones facilitated by the Academy.

That’s not to say that shoo-in contenders like ‘La La Land’, ‘Arrival’ and ‘Moonlight’ are not worthy of being honored. On the contrary, I would take a year like this one any day over a year where ‘A Beautiful Mind’ is the winner and ‘Mulholland Dr.’ is not even nominated. But as with every year of devouring the pleasing accomplishments of cinema from all over the world, there are multiple artists and films on whom the Academy’s preferences will be spectacularly divergent from my own.

So with the congenial feeling that Oscar are not that great a barometer for quality but are far too beguiling to be not left undiscussed, let’s look at some of the work that deserves to be in contention at the Oscars, but is highly likely to be left out in the cold come nominations morning, ranked in order of how galling their respective omissions will be in retrospect:

10. Shia LaBeouf, American Honey (BEST ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE):

Andrea Arnold cast most of her film by picking up first-time actors from the streets and malls of America. She chose one extremely well-known face in ‘Transformers’ and ‘Nymphomaniac’ star Shia LaBeouf, who had frankly never impressed with a display of his acting chops in any film before, which is what makes his electric, irresistibly charming performance here blissfully unexpected.

LaBeouf plays Jake, a veteran member of a travelling crew supposedly selling magazines, who strikes up a relationship with the protagonist, Star, the newest member of the crew and as the crew travels to various locations, the relationship deepens and lightens almost alternatively. It forms a spectacular, dizzying documentary of the naivete and fleeting joys of an impoverished youth.

LaBeouf imbues this spirited connection with such palpable magnetism and inherent richness without requiring Arnold to disclose any backstory to the character. An intimate acquaintance with Jake and his eccentric liberties rendered so seductive by LaBeouf does not require time, as much as it requires an openness. He will hurt you as he does Star, but it will be worth it, thanks to LaBeouf’s mad, spiralling-into-the sky energy.

9. The Handmaiden (BEST ORIGINAL SCORE, BEST CINEMATOGRAPHY, BEST COSTUME DESIGN AND BEST PRODUCTION DESIGN)

A tale so full to the brim with melodrama must be crafted with the utmost artistic authority to warrant the degree of acclaim that ‘The Handmaiden’ has received. Cho Young-wuk’s soaring score undercuts the overt stylisation with a lush, old-fashioned stream of loveliness bolstered by an immaculate representation of the period detail.

Talking about the period detail, the production and costume design is effortlessly in sync with the entire composition of the film as a lore drenched in history, but fictionalized to the point of fantasy. It is utterly pleasing to the eyes, but also feels remarkably lived-in, as if those grandiose sets had been witness to actual residents and those clothes had been tailored for lending the exactly the requisite quantum of texture to the fantasy to ground it.

Towering above all of its technical achievements, though, is ‘The Handmaiden’s’ exuberant, yet studied cinematography. It’s picturesque, but not without a vivid effervescence detailing an entirely cinematic experience that can also transfigure into a tenderly realistic love story as and when required. It exploits nature to densely handsome results with every leaf, every drop of rain endearingly unforgettable.

8. Ralph Fiennes, A Bigger Splash (BEST ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE)

A masterclass in thundering versatility and dangerously esoteric rumblings are what essentially constitute Fiennes’s stupendous turn in ‘A Bigger Splash’. Fiennes has always been among the rare breed of actors whose ease at dancing so elegantly and unconsciously between the loud and the restrained is always breathtaking.

Playing the estranged lover of pop singer Marianne Lane, portrayed expertly by Tilda Swinton, Fiennes brings a frenzied, thrilling and in parts, terrifying vigor to the screen. His Harry is layered with such head-spinning manic that I was left reeling from his intoxicating presence hours after finishing the film.

The highlight, of course, is a scene where he breaks into a dance, whose arresting rhythms are enticingly humorous, but also at the same time lend a sense of dread, as if catastrophe is just at the fringe. It’s a maddening, brilliantly fiery work that has sadly been overlooked in favor of more conventional performances.

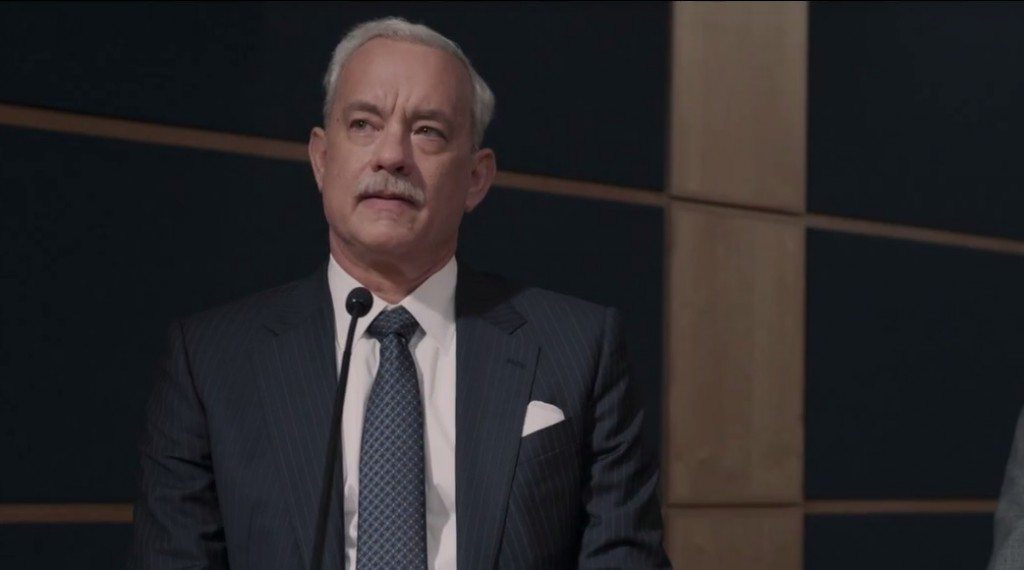

7. Tom Hanks, Sully (BEST ACTOR IN A LEADING ROLE)

“Do we take Tom Hanks for granted now?”: That was a question thrown a lot around the internet when the megastar wasn’t receiving the adequate amount of buzz standard for clinching an Oscar nomination after being snubbed by the Hollywood Foreign Press and the Screen Actors Guild. I do agree with the fact that the amount of gravitas Tom Hanks’s celebrity permits him to bring undoubtedly converges well with his incessantly character-driven performances. I have never seen Tom Hanks playing Tom Hanks, although even if he does, it still won’t be a deterrent to his success rate.

In Clint Eastwood’s deliberately straight-forward, but exquisitely riveting real-life drama, Hanks plays Captain Chelsea “Sully” Sullenberger, a media-ordained hero, who then has to face an investigation because of an emergency landing into the Hudson River executed by him after one of his piloted planes loses its engines due to a bird strike. Sully questions his own decisions just as much of the world around him begin to do the same and Hanks subtly conveys that moral pondering with gorgeous sincerity.

He doesn’t rely on an imitation of the real Sully and centers his performance more on the humanistic complexity of the man in the briefest of scenes and builds a moving parable of how often we disregard the human behind the image on our newspapers and television screens. After such an illustrious career like the one Hanks has had so far, it is natural to take him for granted, but it is unfair to all of his individual accomplishments.

6. Mia Hansen-Løve, Things to Come (BEST ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY)

At 35, Hansen-Løve has crafted a sublime piece on philosophy and its intellectual and practical trappings on human beings who have studied it and comprehended its importance, disguised as a film about a middle-aged woman exploring the purpose of her life after her husband leaves her for another woman. She teaches philosophy and so we observe her lovely little life crumble under the pressure of isolation, even she keeps brushing it off, forcing herself to be substitute loneliness with freedom in her head.

This idea of a new-found freedom leads her to many an adventure, some of which involve her old student, who is referred to as her “prodigy” and finds a disconnect with his desire for radicalism and hers for contentment. Hansen-Løve with her utterly simplistic, but also remarkably profound words, builds such a complex monument to the employment of philosophical renderings to bring us to a better, more appealing will to live, propelled by our imaginations.

She argues, with no rage and all the care in the world, as if a wise auteur were teaching us the meaning of true peace, that looking into the future leaves us with either desperation or hope. We may think for a moment that our circumstances control what we see, but it’s our eyes, and if we set them on something to hang on to, we might be alright.

5. Maren Ade, Toni Erdmann (BEST DIRECTOR)

Keeping aside the glaring fact that since the inception of the Oscars, only four times has a woman been nominated for the Best Director Oscar, this year brought along an unusual plethora of extraordinary work helmed by women. As already mentioned, Mia Hansen-Løve created a melancholic study in philosophy, just as Andrea Arnold presented her epic, vividly fluid re-imagination of young life in the streets of America in ‘American Honey’; Kelly Reichardt put on the screen one of the most stunning paintings of four women drifting into despondency in ‘Certain Women’ and Maren Ade practically chronicled the human experience of an entire generation with ‘Toni Erdmann’.

Ade uses astonishingly latent gestures to convey the biggest of ideas. Sometimes her camera moves to too fast for the eyes to register everything that is bustling with vitality on the screen, conveying a sense of flying time, and in other moments rests upon a singular, largely placid shot for long minutes, driving in the intentions of remarkable density in the most intimate of cinematic languages.

There’s no flashy cinematography to accompany what on paper is one of the most cliched premises. But Ade registers and documents such absurd moments with such devastating humanity that one simply can’t decide whether the proceedings are howl-inducing or acutely moving. That spellbinding combination leaves you only wanting for more.

4. Joel Edgerton and Ruth Negga, Loving (BEST ACTOR IN A LEADING ROLE AND BEST ACTRESS IN A LEADING ROLE):

Jeff Nichols has immense respect for the ordinariness of the Lovings. They are simple, small-town people with no political agendas and no ambitions other than to live their life in peace and raise their children in the place they were raised in. He uses this ordinary tale to produce such hugely emotional moments filled with grounded, yet monumental courage.

Joel Edgerton plays Richard, who falls in love with and marries an African-American girl from his town named Mildred, who is portrayed by Ruth Negga. This marriage is outlawed by the state of Virginia and the case they file leads to the Supreme Court decision that legitimizes all inter-racial marriages. We’re not given sappy courtroom speeches, but small, private moments of the Lovings’ life and what gave them the strength to fight against such radical injustice.

In the hands of lesser actors, ‘Loving’ would’ve been indescribably dull. But Edgerton and Negga breathe such humanity to the story making the characters’ love for each other spoken completely in whispers. This is ground-breaking, understated work that wields such enormous power that it has been surprising and saddening to find it falling off the radar like it has this season. Time will certainly anoint them with better rewards.

3. Mica Levi, Jackie (BEST ORIGINAL SCORE)

After her devilish notes rendered Jonathan Glazer’s ‘Under the Skin’ an unquestionable masterpiece, Levi was assigned to score the aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s assassination seen through the reverberating study of his wife in Pablo Larraín’s ‘Jackie’. I can picture the editing team of the film receiving Levi’s mammoth creations some time into post-production and completely losing their minds. They wouldn’t know what to do with it and would, understandably, end up using it to take their film into a whole new, hypnotic territory.

Levi uses clarinets, violins, drums like they are used in parades to convey such immaculate richness of history, of the urgency of legacy like almost no other composer working on a real-life historical film has. It is at times, wildly playful and sweet to the point of being unsettling and in others, unlike Levi’s ‘Under the Skin’ score, which was recherché and detached, it’s instantly overpowering, and refuses to leave your head once it gets stuck.

Levi has said that she created the music keeping in mind what she thought Jackie would’ve been pleased to hear annotating the most crucial moments of her life. I’m not certain about how she would’ve reacted to it or how the Academy will, but I am prepared to induct Levi into the legion of not just great film composers, but composers in general.

2. Lily Gladstone, Certain Women (BEST ACTRESS IN A SUPPORTING ROLE)

Lily Gladstone says she was ready to pack her bags and leave the city of dreams, without ever getting the opportunity to showcase her talent, before she was cast in Kelly Reichardt’s beautiful film. That broke my heart, for Gladstone gives such a masterclass in artistry in ‘Certain Women’ outshining all of her co-actors who include, among others, Laura Dern, Jared Harris, Michelle Williams and Kristen Stewart.

Gladstone plays Jamie, a rancher living alone in a huge farm with animals being her only company. She has gotten accustomed to this lifestyle until she instinctively decides to step into a night class which she then finds out is being taught by Kristen Stewart, who works in a law firm in a distant city and travels to Jamie’s town just to make some money by taking educational law classes.

There is a scene in ‘Certain Women’ so impeccably crystallized, and so resplendently pristine that I found myself to be an inconsolable mess when it was over. I won’t give it away here, because it is one to be discovered, not hyped. But when you do find it, you will know how much Gladstone contributes to the film’s sensibility, nearly transcending its entire experience, hardly saying anything.

1. Silence (BEST PICTURE)

‘Silence’ is a tough film to love. Fans of Scorsese’s brand of high-wire entertainment will be disappointed by this deliberately slow-paced, solemnly serious masterwork. He has been waiting for 28 years to bring this to the big screen and it stands among the most authoritarian triumphs of his career.

Gilded by Rodrigo Prieto’s sumptuous cinematography and shot in impossibly authentic locations, ‘Silence’ is immensely transportive, drowning you into seas of vast doubt and conflict, if you just give permission. It rises to a level of such subversive genius in its exploration of the search for God’s presence that it leaves bruises on you, instead of comforting solace.

It is a raging, yet silent, humble prayer from as doubtful a Catholic as he is fervent. Scorsese wants to stretch the power of art to become something greater than its intended purposes to entertain or enthrall. He desires to transform into a medium of discovery, in the process gifting us with what might be the single most cerebral, but deeply human cinematic statement on faith.

Read More: Every Best Picture Winner Since 2000, Ranked

You must be logged in to post a comment.