Prime Video’s ‘Radioactive’ stars Rosamund Pike in the role of Marie Curie, one of the greatest and most accomplished scientists in the world. While most people know her for her work on radioactivity and for being the first woman to win a Nobel, there was much more to her complicated and often tumultuous life. Of committed mettle and a dedicated mind, Madame Curie’s story is an inspiration that continues to move people to pursue a life in science. Her biopic reveals many secrets of her personal life, but because Hollywood has a trend of bending facts to serve the dramatization of a story, we wonder how much of ‘Radioactive’ is real. How much of it is based on reality and what parts of it are made up? Let’s find out.

Is Radioactive based on a true story?

Yes, ‘Radioactive’ is based on a true story. The film is adapted from ‘Radioactive: Marier and Pierre Curie, A Tale of Love and Fallout’ by Lauren Redniss. Its director, Marjane Satrapi, wanted the story to be as close to the truth as possible, considering that science was the most important part of Curie’s life and to make a film with scientific discrepancies would not be fair to the story. Redniss had already been very precise about the facts in her book, due to which the film, too, rarely strayed from the truth.

How Accurate is Radioactive movie?

‘Radioactive’ covers not only the scientific achievements of Marie Curie but also focuses on her inner struggles and the scandals that threatened to bring her down. She is known as the first woman to be awarded a Nobel, the only woman to win it twice, and the only person to win in two different fields. Her legacy continued with her family, as her daughter Irene, too, won a Nobel in Chemistry in 1935, along with her husband, Frederic Joliot.

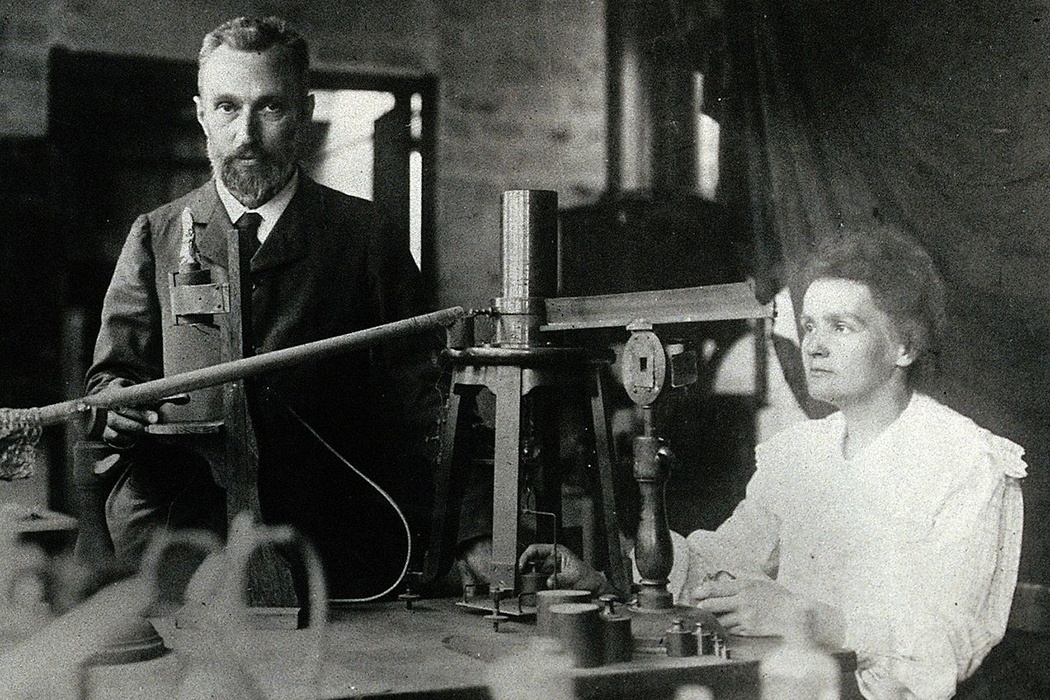

Marie was of Polish origin and came to France to pursue her love for science, an opportunity that her homeland didn’t provide her at the time. While the film shows her meeting with Pierre as a classic romantic movie trope, they were actually introduced to each other by Professor Józef Wierusz-Kowalski, who knew that Marie had been looking for a laboratory space that Pierre could provide. Further, they conducted much of their research in a converted shed behind ESPCI, which had been a medical school dissecting room before they used it to discover and study radioactivity. In fact, the Curies didn’t have a proper lab for a very long time.

In their romantic life, the movie captures their love for bicycle trips and traveling abroad, something that Pierre insists on, time and again. Marie wearing a dark blue dress, instead of a usual bridal gown, on her wedding day is also pretty accurate. She had originally refused his offer of marriage, because she hoped to go back to Poland and get a place at the Krakow University. But when she was denied that and had to pursue her work in Paris, she agreed to the marriage, and chose a dark dress for the wedding so she could go back to her lab in the same clothing.

Radioactivity and the Nobel Prize

After receiving the acclaim for the discovery of radium, Marie and Pierre have a brief conversation about not patenting it and the flood of things like radioactive matches and cigarettes in the market, even the Broadway musical by the name of The Radium Dance- Piff, Paff, Pouff. All of these things have surprisingly been real. There used to be a company called Tho-Radia that would actually sell radioactive beauty cosmetics before the world discovered the harmful effects of radiation.

With such a world-changing discovery, the Curies also received Nobel, but Marie wasn’t initially nominated for her work. As shown in the film, it was Pierre who pushed the committee to have Marie’s name along with his, with some support from Swedish mathematician Magnus Goesta Mittag-Leffler. The Curies, initially, planned to skip the ceremony because they wanted to focus on their work and were also rather ill. However, they were required to be there as the ceremony had every winner deliver a speech. Unlike the film, where only Pierre attends the ceremony, both of them attended it in real life. However, it was only Pierre who gave the speech, and the movie borrows almost entirely from the real speech by him.

The Affair with Paul Langevin

The movie also focuses on Marie’s affair with Paul Langevin, after Pierre’s tragic demise, and rather accurately portrays the media trial that she had to go through. She received the nationalist and anti-Semitic hate at that time, even though she was born a Catholic and had given up on her faith a long time ago. One time, when she returned home from a conference, she found her house surrounded by haters and had to run with her daughters to find refuge in a friend’s house.

Her letters with Paul, which his wife got hold of through a private investigator, were published in the newspapers, following which Paul challenged the journalist, who targeted Marie, to a duel. Fortunately for them, no one fired a shot and the duel was dismissed peacefully. In the midst of this, when she was awarded a second Nobel, Marie was asked not to attend the ceremony because of the scandal surrounding her. But she didn’t pay heed to any of it. Eventually, the affair broke up and Paul never quite left his wife and family, even though Marie had asked him to in her letters.

Marie and Paul’s affair might not have led to anything between them, but interestingly, their families found each other again some decades later. Marie’s granddaughter, Helene Joliot, married Paul’s grandson, Michel Langevin, both of them turning out to be nuclear physicists.

The First World War

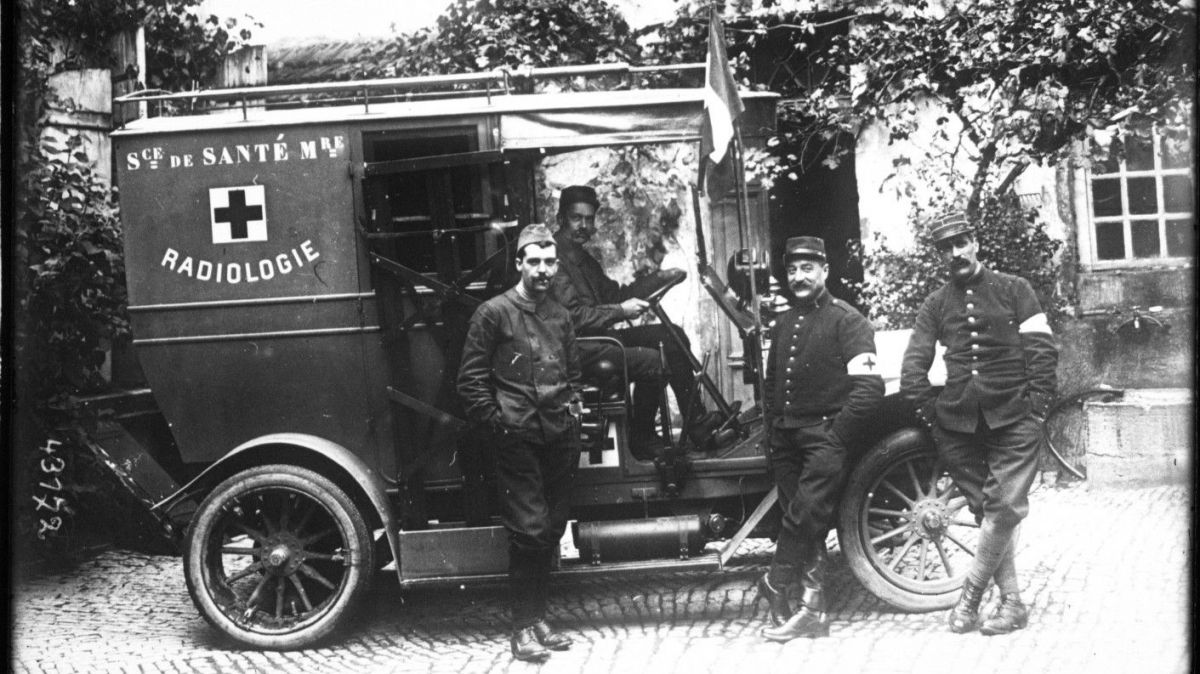

Another fact that the movie highlights is Marie’s contributions during the First World War. Much like in the film, she developed mobile radiography units, which came to be known as Le Petite Curie, to facilitate X-ray services on the field, saving countless lives because of it. In the beginning, it was just her and Irene, but later, they trained other women as well and helped millions of soldiers. Marie became the director of the Red Cross Radiology Service to take complete charge of the task. In the film, she offers her Nobel Prize medal to secure radiological units for the army. In reality, as well, she tried to donate her medals for the war effort and even bought war bonds using her Nobel Prize money.

Considering all of this, it is pretty clear that the movie focuses on all the little details as well as the major accomplishments of Marie Curie’s life. The only thing perhaps that it adds for dramatic effect is her sleeping with the vial of radium by her side. Director Marjane Satrapi explained it as a move to show how important her work was for her. But even this act is rooted in reality. Marie was known to carry test tubes with radioactive isotopes in her pocket and even kept them in her desk drawers.

How did Marie and Pierre Curie die?

In her seemingly perfect life, tragedy strikes when Pierre meets a fateful demise. He is crushed, fracturing his skull, under a horse-drawn cart while crossing the road on a rainy night. He had also been sick due to the radiation poisoning that, also, eventually led to the death of his wife. In reality, too, he had met a similar fate on April 19, 1906. His close ones remarked that his absent-mindedness might have had some role to play in the accident.

Marie died on July 4, 1934, due to the aplastic anemia induced by the exposure to radiation throughout her life. In fact, she had been working in such an environment that all her stuff is radioactive. All her papers and books are too radioactive to touch. They are sealed away in lead-lined boxes, and anyone who needs to read them has to gear themselves against radiation poisoning. Both Pierre and Marie were buried at the cemetery in Sceaux, but in 1995, they were transferred to the Paris Pantheon, making Marie the first woman to be buried there on her own merits. The level of radioactivity in their bodies was so much that their remains were sealed off in a box with lead lining.

Pierre and Marie dedicated their life to radioactivity and their daughter, Irene, furthered their work through her research with her husband, Frédéric Joliot. They received a Nobel for their work on artificial radioactivity, but as Marie had feared, they, too, suffered from radiation poisoning and died because of it. Irene died in 1956, at the age of 58, due to leukemia, and Frédéric died in 1958.

Read More: Best Movies About Scientists

You must be logged in to post a comment.