Brazenly bizarre, absurdly violent, disgustingly tasteless, intrinsically crass, practically implausible and thematically intimidating – the choosiest of unpleasantries could be doled out on Sergio Leone’s ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ (1966). While a film critic is welcome to castigate this apparent rendezvous with ‘cinematic trash’ to the corridor of infamy, one would do well to remember that the auteur intended it to be exactly so. Notwithstanding, a cinephile’s life doesn’t really stay the same once he/she experiences the movie for reasons that could be a little difficult to explain. Strenuous as it might be, impossible it isn’t! One could measly go through the film’s text in order to get a firsthand experience.

There can be an extensive debate over how a film like ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ ought to be categorized. Although it could be rightfully described as an epic Western, the biggest proponents of the genre might just be a tiny winy uncomfortable with the proposition. The backgrounders aren’t really very difficult to gauge. For one, it deglamourizes the ingrained heroism usually portrayed in typical Westerns. Two, it shows the ugly underbelly of the American Civil War. Last but not the least; it makes a distinct attempt at deconstructing the stereotyped notion of Americanism. A John Wayne or a John Ford might have personally referred it to the notorious ‘House Un-American Activities Committee’ (HUAC) had it been a rank American venture. Thankfully, nothing of the sorts transpired and we had Sergio Leone turn in one of the most innovative creations in global cinema.

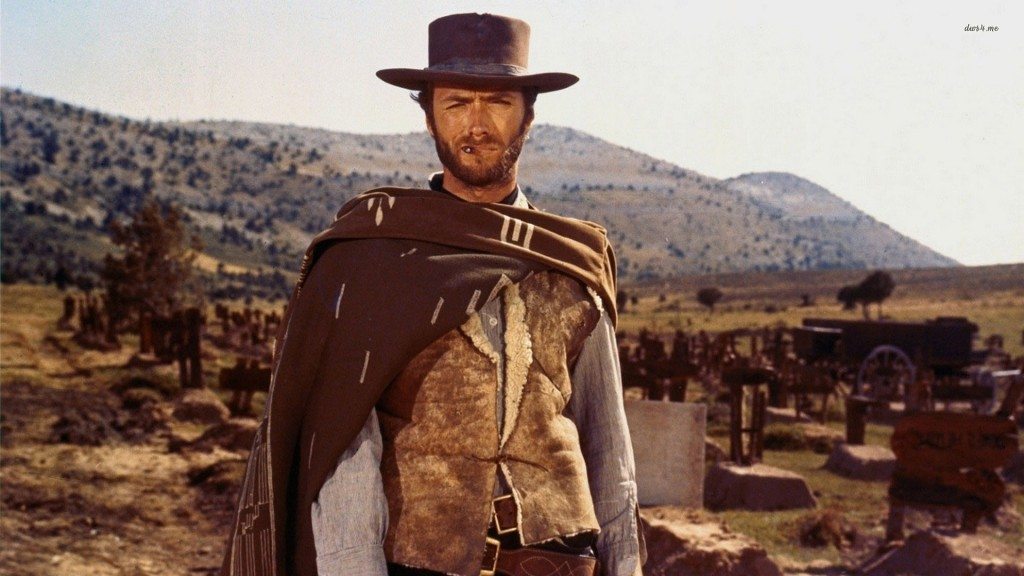

The widescreen cinematography, the long shots, the extreme close-ups, the cynical characters, the insensitive mercenaries, the crude ways of Western life, the ragged gunslingers, beautiful landscapes – multiple markers dot the plotline. However, when one takes a closer look at the movie; it becomes conspicuous that the entire story is about how three marksmen run after a cache of confederate gold buried in a cemetery. While one wonders how the director fills the rest of the film, there never really is a shortage of entertainment and action. Not very often have filmmakers so graciously dabbled with the synergy of art and commerce. The unending chases, the tension in the air, the ambivalent nature of characters and the rather stark portrayal of the human race – there is something deeply ominous about the movie.

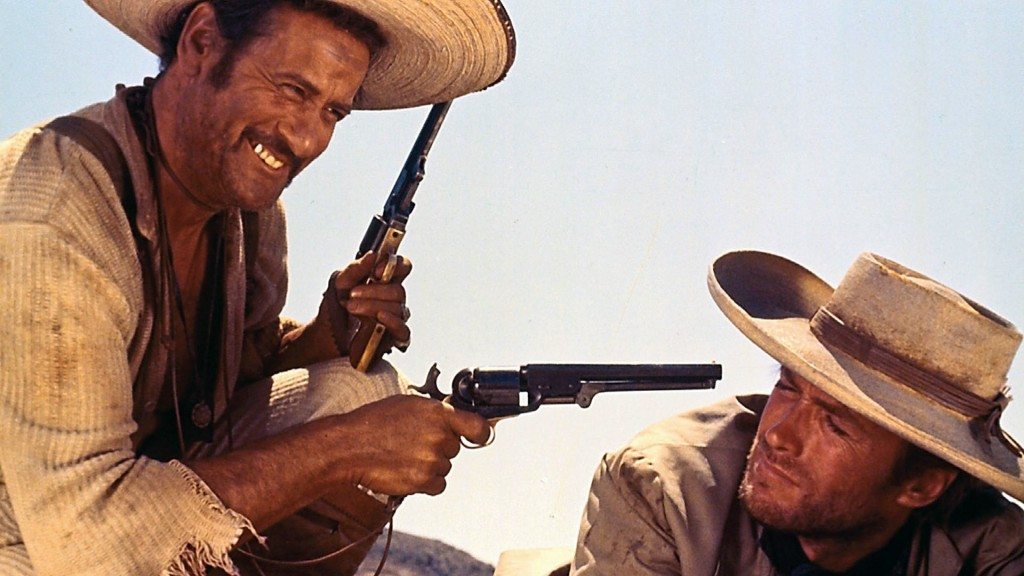

Tuco, who embodies the titular Ugly, represents a mix of grit, resilience and blunt humour. It would probably be justice done if it were to be said that it is Tuco who acts as the connection between the Good and the Bad. Critics argue that Leone had invested his maximum energy in shaping Tuco’s character. The methodical Eli Wallach plays the role with a rare precision and zeal.

The ruthless Angel Eyes embodying the titular Bad is menacing to say the least. He never fails to finish his task, which is invariably exterminating someone. With his calm demeanour and immaculate way of dealing with things, Angel Eyes creates a sense of paranoia. The ragged Lee Van Cleef acts out the part of Angel Eyes with absolute élan.

However, Clint Eastwood steals the show as the titular Good. As Blondie, Eastwood represents the perfect anti-hero. However, people might find some solace when he empathizes with the soldiers entangled in the civil war and blames it for wasting a lot of precious lives. In an obvious clash of loyalties, we find that Blondie is at once greedy and graceful. Greedy for he too is drawn towards the gold as much as the two other central characters and graceful for there is a certain amount of finesse about his actions. No wonder that people tend to take sides.

The final three-way dual scene could be considered to be the pinnacle, something that would remain etched in the memory of cinephiles forever. It is not what happens in the scene but the way things unfold is what holds it together. Accompanied by a fabulous piece of music by the legendary Ennio Morricone, the tension builds up as we go from extreme long shots to extreme close-up shots of the characters as they prepare for the final showdown to have their hands on the gold.

The movie doesn’t have too many dialogues and practically actions speak louder than words. However, dialogues also differentiate the inherent differences between the characters. While Tuco is talkative and hardly ever stops blabbering, Blondie and Angel Eyes spare very few words.

When the film was released, a lot of critics panned it simply because it was a Spaghetti Western. However, with time, the reviews have turned positive and a lot of scholars have rated it as one of the finest movies of all time. If we take a keen look at the movie, we might even be tempted to call it an anti-war film. Additionally, capitalism and the lust for individual prosperity act on the background as definite subtexts. A box office success, it was the final part of the ‘Dollars Trilogy’. With Spain and Italy acting as the locales for the shooting process, the setting seems even more dry and arid. Leone actually branded the film as a satirical take on the usual breed of Westerns made till then.

While a lot of the shots seem make believe, the auteur perfectly crafts the suspension of disbelief amongst his viewers. With the cinematography by Tonino Delli Colli being an absolute work of art, Quentin Tarantino rates it as the best directed movie of all time. It is difficult to believe that Eastwood was a Hollywood reject then. With a shoestring budget, there is almost a B-movie feeling. But boy does the film work! While Leone was instrumental in directing two other timeless masterpieces, ‘Once Upon a Time in the West’ (1968) and ‘Once Upon a Time in America’ (1984), this remains to be his most intimate work.

While one can argue that cinema as an art form isn’t really represented by ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’, the fact remains that this film has inspired more filmmakers than many other critically acclaimed movies. A hundred years from now, when one looks at the history of cinema, ‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ would surely feature as an endeavour that provided a fresh lease of life to a genre that was fast losing relevance.

Read More: The 10 Best Westerns of the 21st Century

You must be logged in to post a comment.