I remember planning to watch ‘The Master’ in installments because it was a school night and I didn’t wish to stay up late. The lone Anderson film I had seen by that point was ‘There Will Be Blood’ which many considered to be the greatest film of the 2000s, with that dazzling Daniel Day-Lewis performance bustling with raw human emotion that somehow translated to such profundity on the screen that it spoke to a truth essentially timeless and rising above the very obscure and specific setting Anderson chose for his film. What I was about to see, though, managed to be even more obscure and specific in its details, while reducing its accessibility but intensifying the ambiguity to a degree it would be hard to analyse, let alone draw any tangible conclusions from the experience I had. Needless to say, I watched it in one go.

Anderson has been attacked for not appropriately handling the Scientology idea many believe the film focuses on. The problem with that characterization is just that: it’s not solely focused on exploring the ideas and seductive pull that led to the advent of these cults in a time where everyone felt unfulfilled after the war, let only just Scientology. Anderson moves past all these simplistic generalizations to create something that’s not easily understood or even intended to be, but something that becomes poetic and harrowing at the same time as he presents to his befuddled audience the absurdly grounded realities in the most surrealistic of times.

Anderson explores the idea of image versus reality to ask the question: what dictates and foresees our actions more, the way we wish to see the world, or the way we it actually is? The master keeps asking Freddie about the time he met him years ago. It’s virtually impossible that Freddie’s small-town life in Lynn, Massachusetts would have collided any time with The Master’s constantly moving, high-society world before he left for the war. It is just his desire to have been in contact with Freddie’s being, the animalistic free spirit whose perverse predilection is strangely attractive to him; to have already known him, so that mastering him would come to him naturally.

He says to Freddie at one point, inviting him to his daughter’s wedding, “Your memories aren’t invited.” As the film progresses, and as we learn more of the master’s “processing”, he seems to deal primarily in memories. But those memories, which he proclaims to have arisen from the past lives of his clients, are actually their imaginations driven by him to fully convince them that their ideologies and belief systems have been transformed within minutes of him working on them. It could be called a sham, or it could be, as is elemental to the success of such cults, highly effective. At the end of the day, we only believe what we wish to believe. So when he tells Freddie his memories aren’t invited, he desires a clean slate for him to make the man out of Freddie he wants, not what his life so far would have him be.

Of course, the master knows much less of Freddie than he would have both Freddie and himself believe. His enchantment with Freddie lies in his image of him, and his control over him loses and gains power nearly alternatively with every passing day he finds him in his company. Freddie would beat people up for questioning Lancaster one day, and himself declare his methods to be utter fabrication the other. “You’re making this shit up!”, he says to him in that jail cell, but his arbitrary tendencies would bring him back to his clan again, fully surrendered to the “Cause”.

In one of the more realistically rendered sardonic, ‘The Master’ finds the clan at a New York City party hosted by one of the high-society people to introduce the very forward and intellectual community of the town to the master’s works. As he begins to charm his way into the heads of the people present, a certain cynic who preaches science begins to question Dodd’s teachings. This leads to the master, who first ignores his inquiries, embarrassing himself in front of the entire party by losing his temper and revealing a far less cultured facade. Equally revealing is a scene that follows, where his wife, Peggy, dismisses the eccentric skepticism of the big city, fueling her husband’s ego; her devotion coming off more as ambition than affection.

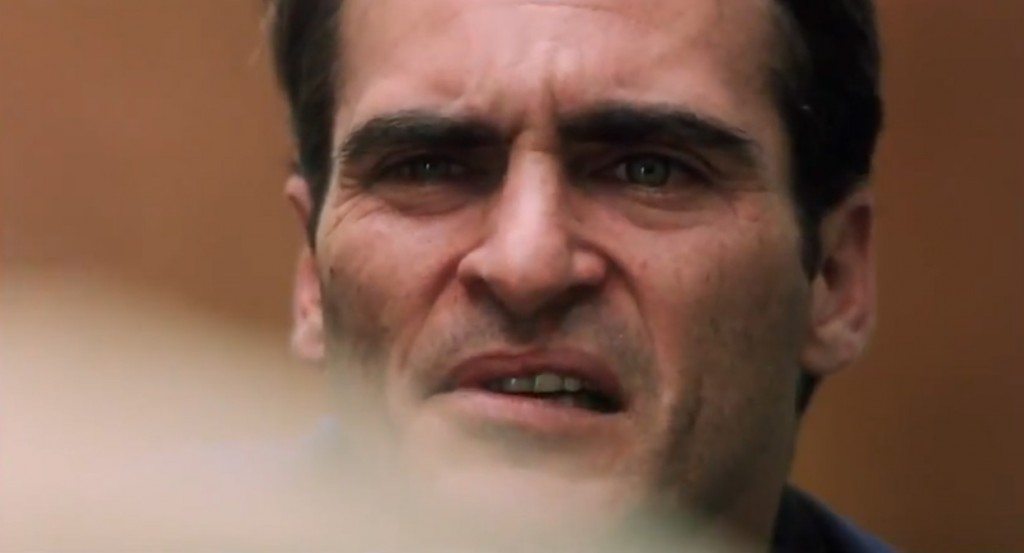

This brings to mind how much this film relies on the performances of its principal cast to lay the distance between the audience and the characters as well as the situations that surround them. They are not entirely relatable but become such engrossing, complicated, twisted images of the grand ideas Anderson wishes to explore. Amy Adams and Philip Seymour Hoffman use their impeccably reliable voices to annotate the lack of morality in their characters. Hoffman, especially uses it to dynamically paint a picture so deeply mesmerizing, you might keep thinking about the character’s motivations for days later. Joaquin Phoenix, on the other hand, uses his stooped shoulders and raging limbs to craft moments causing alternate bouts of sympathy and repulsion in the viewer.

‘The Master’, from my perspective is an intellectually concealed love story. It stems from a desire to be mastered and a desire to master from the two lovers and matures into a more serene bond that exists much more in visions and dreams than in the realities of the Post-War era. “I don’t think Freddie is as committed to the Cause as the Cause is to him.”, an envious Amy Adams observes at one point in the film. Freddie cannot live under control, while Lancaster cannot live without having a control so total in its magnitude it becomes his dearest passion. Only a filmmaker like Anderson would choose such perversely inclined men to be the center of a love story. He paints the big strokes first (the visual pizzazz of the 70 mm is breathtaking) and then focuses on elucidating the finer details; something Steven Spielberg credited Stanley Kubrick with. ‘The Master’ is essentially a Kubrick film: an experience before it is an ideological meditation and a painting before one can attach any meaning to it. The meaning will most certainly change with every viewer, and with the inevitable passing of time. I cannot wait to discover what it eventually becomes.

Read More: The 5 Best Performances of Philip Seymour Hoffman

You must be logged in to post a comment.