No one quite does domestic dramas like Sam Mendes. Looking at ‘American Beauty’ and ‘Revolutionary Road’ in close consonance, the tensions, the staging, the set pieces, and the conversations set around them, it is really not difficult to arrive at Mendes’ strong theatre background — the mastery just shows itself quite naturally. Even though by now Mendes’ filmography has grown quite prolific, housing epic war dramas and two blockbuster Bond films, I am going to keep the discussion intentionally centred on ‘Revolutionary Road’ and ‘American Beauty’, two of his most affecting films for me, and later dive deeper into the latter.

The two films are thematically similar in many ways. Both ‘American Beauty’ and ‘Revolutionary Road’ prove to be effective case studies, and critiques at the same time, of the ever elusive American Middle Class and the domestic struggles hidden behind crumbling marriages, unpaid mortgages, the temporary lure of infidelity, the fear and pressure of children being raised in a rough atmosphere such as this, and to top it all off, the ever elusive American dream: simply trying to make it is perhaps an age long exercise that several patrons undertake, only to wind up at the same spot as Lester Burnham. It’s almost as if the American suburban dream that has for now long been advertised on billboards and outside to-let signs of duplex properties has lost its sheen and been turned on its head, by sheer virtue of the broken individuals inside them.

What’s also interesting is that despite the setting being completely, eerily similar in both films, the nature of domestic and marital struggles, and that of a midlife crisis, a dominant theme in ‘American Beauty’, are of a rather global nature — to be unsure of what to look forward to next is but the most human thing. That is what I think ‘American Beauty’ captures quite beautifully, and if I am to put it in more words, quite heartbreakingly and how Mendes does it while retaining all of these properties in his narrative that make the film experience what it is, is actually the man’s craft; something that I am in complete awe of.

What’s even the more interesting is that this particular period, the turn of the century (and the millennium), had a number of such films release within conspicuously close periods of time, including ‘Magnolia’, ‘Fight Club’ and this one, calling out the false ideal of corporate consumerism, the image of a perfect life, and urging the viewer to look for more, simply more. Of them, I find ‘Fight Club’ to be eerily in the same vein as ‘American Beauty’, albeit without the uber-cool sermonising and ultra-violence. Most people would call me whacked in the head for putting ‘Fight Club’ and ‘American Beauty’ in the same vein, but a closer examination of their themes and not their structure as films would reveal this discussion’s merit. Anyhow, without further ado and after having sufficiently set the stage for a very ripe discussion, let’s dive into what ‘American Beauty’ and particularly its ending meant for you.

The Ending, Explained

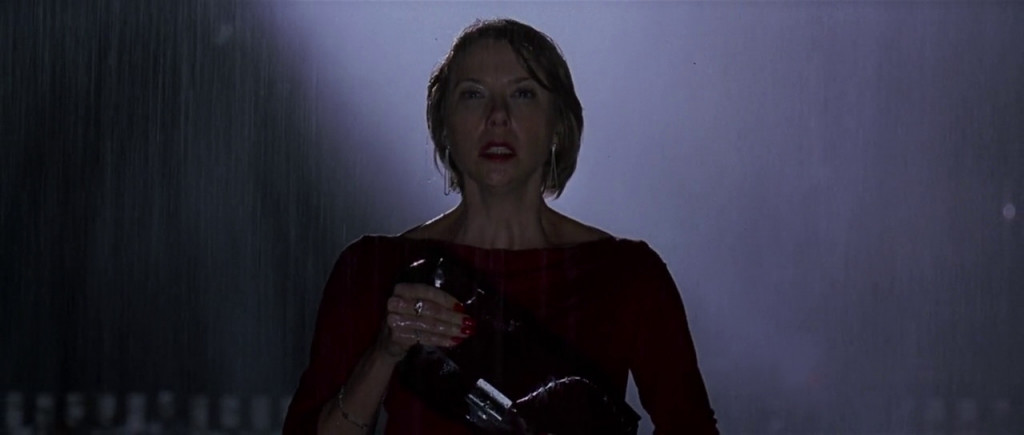

I suppose the culmination of the third act begins with Lester’s discovery of Carolyn’s infidelity with her professional lawyer Buddy Kane, to which he acts rather indifferently, and might I add, in an absurdly comical fashion. The two call off the affair, with Buddy citing an expensive divorce and having too much to deal with. She doesn’t return home until late that night. She is later shown driving to her place, reaching for the gun in her glove compartment, and falsely confiding in herself as she repeatedly utters that she refused to be a victim to herself.

Back at the Durnhams’, Jane arrives with Angela as Lester flirts with her, much to Jane’s resentment. At the Fitts’, an already suspicious Frank searches Ricky’s room to uncover footage of a nude Lester lifting weights that Ricky had shot accidentally earlier in the film, confirming his suspicion. To add to it all, Frank mistakenly watches Ricky at Lester’s place and misconstrues them as indulging in sexual acts, upon which he violently confronts Ricky when he is back home, threatening to cast him out for his homosexuality. Ricky, now frustrated, accepts the claim and uses it to urge him to expel him from their home. Ricky later goes to Jane and asks her to elope with him to New York. While she is having a spat with Angela over the same and her father’s advances towards Angela, Ricky defends Jane telling Angela that she was boring and ordinary and insecure about the same, something that immediately gets to her as we see her sobbing in the stairway shortly after.

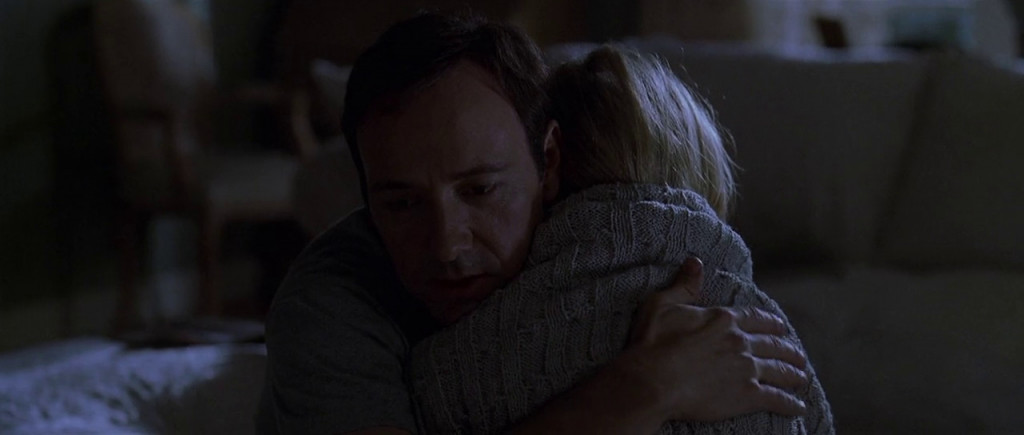

A heartbroken Frank later confronts Lester in the garage hoping for some respite, and tries to kiss him revealing his own closeted homosexual tendencies beneath a homophobic exterior, which Lester mistakenly dismisses. Later, Lester catches a saddened Angela in their house, and the two proceed to have a tender conversation about beauty, with Lester telling her how beautiful she was. They kiss, and right before they are about to have sex, Angela reveals she is a virgin, contrary to what she had been portraying before. Lester decides not to have sex with her, and instead the two end up sharing a rather tender conversation in the kitchen.

Just as Angela excuses herself to go to the bathroom, Lester seemingly reminisces older times with his family by looking at a photograph, just as he is shot in the head from the back by Frank, who repentantly returns to his place, bloodied. As we see the family, especially Carolyn mourning Lester’s loss, an intrigued Ricky stares over Lester’s dead body, something that to him is a thing of beauty. The film closes with a monologue by Lester as we see a montage of Lester’s life, just as it seems to be flashing in front of his eyes.

“I guess I could be pretty pissed off about what happened to me; but it’s hard to stay mad when there’s so much beauty in the world. Sometimes, I feel like I’m seeing it all at once, and it’s too much – My heart fills up like a balloon that’s about to burst And then I remember to relax, and stop trying to hold on to it. And then it flows through me like rain. And, I can’t feel anything but gratitude for every single moment of my stupid little life. You have no idea what I’m talking about, I’m sure. But, don’t worry. You will someday.”

I’d say that is one of the most bittersweet endings that I have seen in a long time, although more bitter than sweet, since in its final bits, it asks the most dangerous question. It doesn’t let you go home with the security of it all being fiction. Dreadfully so, it asks you to self-reflect. Now to some pining questions:

Why don’t Lester and Angela Have Sex?

In the moment that Angela reveals to Lester that she is not a virgin, his outlook towards her completely changes. He begins to see her not as an object that inspired lust in him, but as an object of beauty. Even while she is insecure and feels stupid for her decision, he earnestly comforts her, almost as he would a daughter, that she was beautiful, and confides in her about his family.

Did Carolyn Want to Shoot Lester?

Lester’s internal rebellion and convenient shunning of everything of consequence was bound to draw both inspiration and hatred. As her illicit relationship with Buddy comes to an end, Carolyn somehow begins to blame Lester for it, even unreasonably so, despite being the one who cheated. Frank’s indifference to the whole scenario adds to her rage and guilt, as she arrives at her house, fully prepared to shoot Lester.

Why did Frank shoot Lester?

This one is quite simple actually. Frank was an uptight man and it wasn’t difficult to see that he was hiding more than he could account for; his very apprehension towards everything pointed to a lot of bottled up emotions and facts about him. His hard exterior eventually comes undone as he gives in and seeks physical support in Lester who he thinks is homosexual too. He is, in a way, inspired by how Lester embraced his own (perceived) homosexuality without a care in the world and made his wife agree to the arrangement, all of which is false but it is regardless what he construes from the conversation. Upon being rebuffed, it is Frank’s denial that made him kill Lester. Since his advances and a sort of acceptance to himself bore no fruit, he simply couldn’t continue living with that information out there, which is precisely why he had kept it bottled in for so long: Society.

Themes

While everybody attached to the film, including the director, the writer Alan Ball, and several cineastes and film academicians who have put the film under a microscope for judging its various themes and motifs have deliberately refused to offer a single interpretation of the film, or a single theme that got to them, for me, it would be desire, and that too, one of an innate kind; at least in an overarching manner, since there are several of them that I believe find their roots in this one.

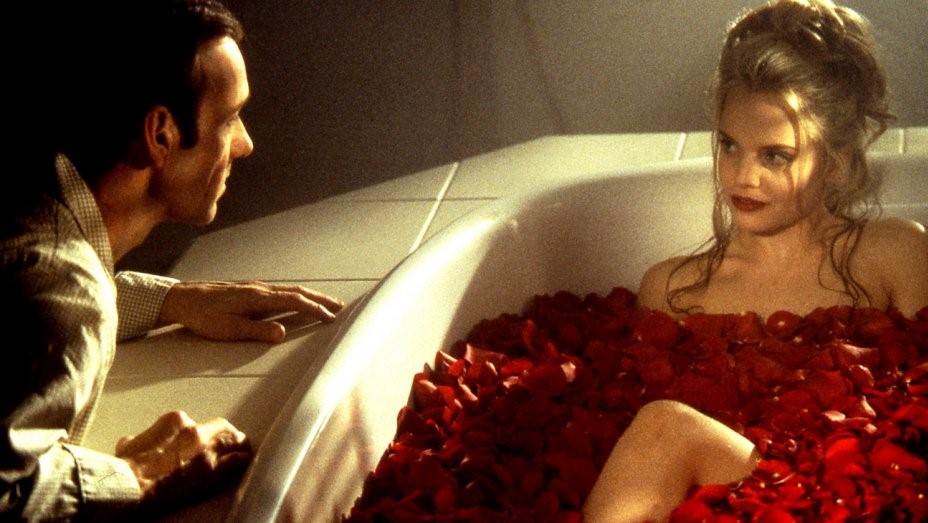

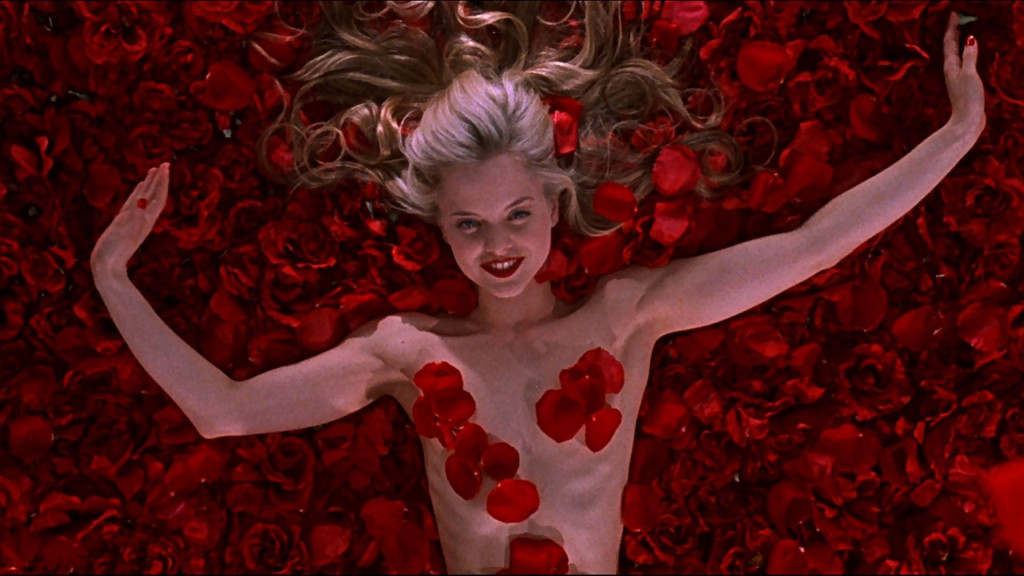

All the subsequent themes pertaining to the major characters stem from their desire to establish something they don’t have or be something that they aren’t. In that, I then interpret ‘American Beauty’ as a devious ideal, an impossibly high standard or benchmark, something unattainable, and yet something that has an all overcoming draw, even if in vain, as all the main characters in the story act upon it: desire. The film’s deliberate usage of sometimes surreal and sometimes remarkably real imagery with a saturated usage of red, the colour of desire accentuates that: be it the roses or the red door at the entrance of the Durnhams’ house.

However, at this point I also must reiterate that the film is about this journey that the characters undertake: towards the attainment of those desires. The destination to that journey is never reached, but all of them in the process realise the fleeting nature of beauty in and of itself, as something that can be found in the simplest of things, as they break away from their self-imposed imprisonment and exile.

The prison for each of them would be such: for Lester, it would be that of mundanity and having given in to a certain sedation that comes naturally as one progresses through life without actually getting somewhere. For Carolyn, the self-imposed prison is her own flailing image of success and material pleasures she associates herself with. For Jane and Angela, it would be their own teenage insecurities, while for Ricky, it would be the grasp of his abusive father. The most surprising revelation for me is Frank’s prison — his innate homosexual tendencies that he’d harboured in secret for far too long for fear of being shunned by the society as a marine.

Having said that, beautiful could thus be anything: an escape from your moribund life, a temporary refuge from your troubled marriage, your daughter’s high school friend, a long yearned for consonance in thoughts even if from a stranger or a polythene flying about in the wind. Of course, that realisation and the journey has a bittersweet end for most, especially for Lester who loses his life in the process, but I suspect by that point in the film, it didn’t matter to him. Even in his final moments, just before Frank shoots him in the head, he seems to be in a euphoric, almost nirvanic state, having attained a sort of enlightenment that he always sought. The gunshot echoes through multiple shots showing the characters’ reactions to it, accompanied by how the characters’ lives would come to change in the wake of that incident.

Final Word

The reason for the longevity and a certain timeless appeal for these films that released at the turn of the century is a certain commonality among them, of shunning the downside of everything that modernism brought about. ‘American Beauty’ is a prime example of that. It touches expertly upon the universally tough themes of mental imprisonment, alienation, of beauty, the necessity of conformity, and of a midlife crisis. Having said that, in all its current consonance, I have no desire to catch it sometime again in the near future, because its relevance oft comes at a cost: self-reflection. Someone who has watched the film and been affected by it simply cannot claim that somehow the morosities of their life, however few, didn’t play out in front of their eyes as Lester delivered the final monologue. If you somehow didn’t or still haven’t, “you will someday”.

Read More in Explainers: John Wick 3 | Terminator 2: Judgement Day | Saw

You must be logged in to post a comment.