Netflix’ latest Italian language feature, as I have already stated in my positive review for the film, is a dollop of positivity and child-like wonder, but a major credit for that goes to the ending of the film. Somewhere deep within my mind, simply out of fear, especially given the dreary direction the film seemed to be headed in towards the middle, I feared that the ending of the film too would leave the viewer as such. Thankfully, that’s not the case and that is what we are here to elucidate upon.

That the passage of time in the film is essentially a lifetime lived for our protagonist, the titular man with no gravity, who in the absence of tethering to the ground would simply float away, something that begins on a rather amusing note but quickly develops into an elongated allegory of sorts that we will shortly discuss, just bears deeper meaning to when the ending basically comes a full circle with the beginning of the film. In a way, the tonal shift also quietly encompasses the shift for many of us between childhood and adulthood, something that is rather abrupt.

I then have a special place in my heart for films that have endings that are essentially callbacks to the first act that a lot of us think merely as setups for the film to unveil, and just as that, something as trivial as a pink backpack becomes something beautiful towards the end. Without saying too much, I now move to presenting what I thought of the uplifting and alleviating ending of ‘The Man Without Gravity’.

The Many Phases of Oscar’s LIfe

Since the beginning of his childhood and as far as he could remember, Oscar spent his life in reservation, solitude and even confinement within his home, tied down to the ground by both literal and figurative weights, frustrated on being limited in what he could do and yet staying powerless, equating himself with the worldwide icon in Batman.

The agents for this are surely different: at first, his orthodox Grandmother, and followed by that, his mother, who initially is all up for Oscar wanting to see the world outside, but quickly panics upon learning that Oscar had inadvertently let known his secret to Agata, leading to him and Agata being separated as kids. The two major shifts in his personality, and the way he lives, are marked by the deaths of the two most important women in his life, beginning with his grandmother, following which, Oscar and his mother move to a secluded place in the mountains, and Oscar too, becomes a relatively quieter person than before.

It is during this phase that we actually see something dying within Oscar, who grows increasingly accustomed to a silent, conflicted way of life, with the child in him long gone, yet only rarely evoked in the chuckles he occasionally let out. He spends his day tethered to the pink backpack Agata gave him, reading and drinking and idling with other men from his scarcely populated place of residence. Something awakens in him when he sees an ad of the reality TV show, Extraordinary Men, and quite likely regarding himself as one, he elopes from home to go to the show in Bruxxels, leaving his mother a note, and thus begins his journey to global stardom and popularity, and with that on the rise, also one of self-discovery.

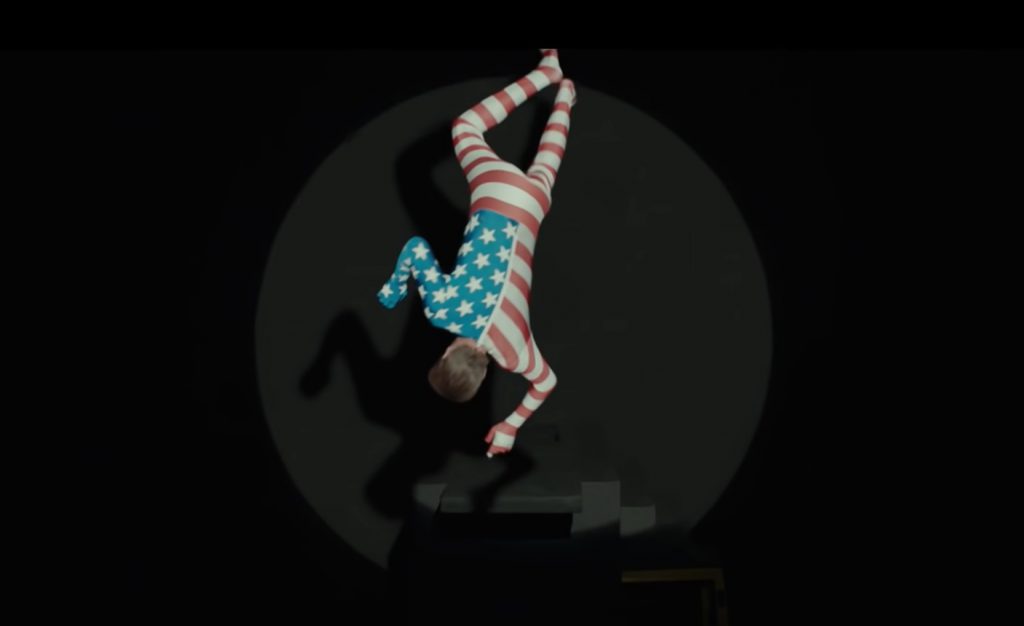

With one thing leading to another, and Oscar making it big with the help of his agent David, he struggles to maintain a sense of identity and individualism, feeling himself not too different from the animals people paid to watch at circuses. The same evocation of being a show pony for hire is brought in front of his eyes as a pink painted donkey lines up for a shoot right after him, and the rejection of his real life story for something more dramatic that would sell better proves to be his tipping point. He flips out on live TV at his audiences, and as a way out, he and David decide to have him declared dead so that he could seek an out from this life of show business that he despised and begin life anew.

The Ending, Explained

Yet again, he isolates himself and upon the passing of his mother and losing most of his money owing to unfulfilled contracts, the latter of which he doesn’t seem to care about anyway, he moves to work as a receptionist at a city hotel, now being tethered to a wheelchair as his guise of not walking normally.

Yet again, he leads a quiet life but is loved by his co-workers. The third act, then, almost subsumes the structure of the second act in introducing to him something from his past that disrupts his tranquillity and forces Oscar to seek something more meaningful. The external factor this time is Agata, who is now presumably a prostitute for hire and frequents the hotel Oscar works at with clients regularly, recognising him by virtue of the pink backpack that he still carries around.

The two immediately reconnect and reconcile, bonding over their somewhat shared misery, even as it becomes increasingly obvious that the love between them wasn’t dead. Agata rekindles that by inviting Oscar to her room one night, where the two have fun dancing, and presumably sleep with each other, silently confessing their love for each other, yet still quietly returning to their lives the next day.

The next time Agata walks in with a client, she realises her love for Oscar, and after abandoning her client, confronts Oscar over his inability to take charge for himself despite being gifted, and failing to follow what his heart truly wanted, being bogged down by other’s desires and how others wanted to shape him or benefit off of his abilities, much like herself. In a classic epiphany, Oscar now realises something, now seeking joy in the simpler things in life.

In a beautifully filmed scene chock full of colours, he carries Agata on his back running carefreely through the city, as if she was her backpack dressed in pink, keeping him on the Earth. On the contrary though, for the first time in the film, she is the one to have given him the freedom to think for himself and dream better things for himself. The two move out from the hotel and relocate to Oscar’s childhood home, now beginning to live together in what is a sweet, presumable happily ever after for the two.

However, the sweetness doesn’t end here, since Oscar now is shown leaving for his work, wearing a new backpack. His job? Cleaning windows of skyscrapers dressed as Batman. This may sound too cheesy for an ending to a film about a character’s internal struggles, but the magic occurs when you see it: when you see Oscar cleaning the windows outside an old age home in the skyscraper, bringing joy to the numerous joyless residents in there dressed as their icon, and his own, it is difficult to not be overcome by emotions.

For the first time since the beginning of the film, we see Oscar truly happy, and in saying so, I would like to believe that he truly had somehow discovered his purpose in life. In stark contrast to anybody else with the same abilities who would have chosen either the fame or chosen a superhero life of vanity, Oscar decides to be a true superhero, something much simpler, yet much happier. Oscar flourishes, even as the man with no gravity perishes.

Read More: The Man Without Gravity Review

You must be logged in to post a comment.