When you watch a John Carpenter film, one of either two things is equally plausible in happening: you either love it beyond reason, or you detest it with all that you feel. Given the two extremes that these are, it would be safe to say that there is no middle ground when it comes to Carpenter’s films. ‘The Thing’ is a film that has been on either ends of the wide spectrum amid much discussion and deliberation, and has still left room for some more of the same. As of now, it’s been quite some time since the film was released, and a tour down the lane recounting the tumultuous journey of this film from what was termed to be the most hated film of all time to a cult classic and one of the best horror films ever made would seem all but necessary.

Back when the film released in 1982, it didn’t polarise audiences, instead uniting them in their common hatred for the film. Critics too echoed that sentiment and the film was quickly labelled as one of the worst films of the 80s atleast. Terms like “quintessential moron movie of the 80s”, “instant junk”, “cold and sterile”, “wretched excess” and the like were thrown around for the film, and the meagre box office returns mirrored the same. The impacts too were almost immediate. John Carpenter lost out on a couple of directing jobs after the film’s perceived failure, and had to return to low budget filmmaking, a subgenre of sorts where too the director didn’t fail to make his mark. The film, however experienced a resurgence and was seen in a different light when it was released on home media, almost overnight. Let me leave you hanging at that very thought as I vow to return to the specifics of its initial failure and resurgence, and which of the two vastly polarised sides find my biding in a later section. For now, we begin discussing the film itself. Read on.

Plot Summary

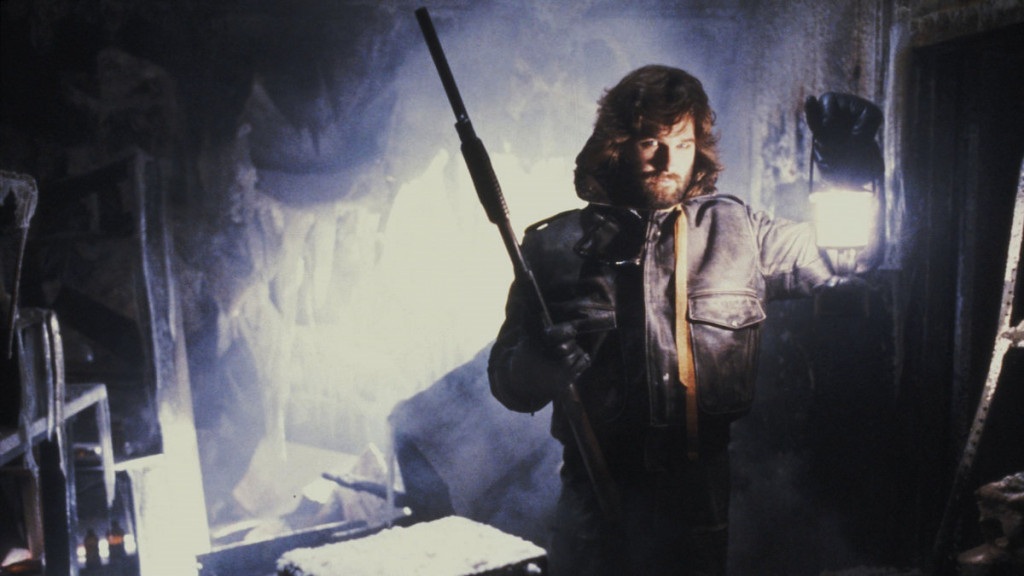

It is reasonable to assume that since you are here, you already know what happens in the film. ‘The Thing’ is based on the 1938 novel by John W. Campbell Jr. ‘Who Goes There’, earlier adapted to screen in 1951 under the title ‘The Thing from Another World’. In that, the 1982 film would also be termed as a remake of the 1951 version. The plot involves an extra-terrestrial being, eponymously titled so, capable of assimilating, ‘digesting’ and imitating the organism it has ingested. At the centre of the story is a group of American researchers and their helicopter pilot in Antarctica, who encounter the Thing, and now must deal with it and some of their own comrades who may have been infected by the parasitic entity.

The origins of the otherworldly entity may be traced back to close to a hundred thousand years, when the space vessel shown in the beginning of the film may have crash landed on the Antarctic continent with the purpose of assimilating an intelligent population, and as is revealed later, take over the world through steady growth. The vessel is discovered by a Norwegian scout group in the Antarctic where they encounter the Thing and meet an ill-fated end. The Thing makes its way from the Norwegian camp to a US research station by assuming the identity of a husky dog, infiltrating the station and beginning his reign of terror on the men there. What ensues is a gory struggle to contain the Thing from propagating itself and taking other hostages, and genuine paranoid fear as the comrades begin turning on each other when pressure mounts and some tough decisions are made.

The Film’s Failure and Resurgence: What Caused It?

A remarkable thing about the film, having established its high and low points of popularity among the audiences, would be that in between the period of time separating the two, discussions around the film didn’t die down, as is also true for most controversial works of art. If you have seen the film, and I assume that you have, irrespective of the fact whether you liked it or not, you will agree that the film was stirring to say the least, and something this rare at that point in time would be worthy of inciting discussions.

Getting further, in the period separating the film being bombed and the film being revitalised, a number of theories were given by ‘experts’ to make sense of what just conspired. The major one among them would be stiff competition from the other ‘alien’ release close to this film’s release, Spielberg’s blockbuster ‘E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial’, that significantly harmed ‘The Thing’s prospects. Both the films dealt with the arrival of extra-terrestrial visitors on Earth, but while Spielberg’s film shed a warm light and showed the alien in a positive light, ‘The Thing’ went all out with its gory display of the shape shifting alien. Naturally, the first one drew in the numbers and appealed more to the American audiences, especially families in a recession hit US. The latter with its nihilistic display of violence, squirmish blood and the insides of people and monsters, coupled with an unclear resolution at its end naturally repelled audiences looking for an escape that ‘E.T’ was eventually able to offer.

Following its home release though, critical stance on the film became more positive and the audience too, started looking at the film as a terrorising B-Movie, made exactly in that vein and for that purpose. Following the immediate reassessment, as the years passed, praise for the film, especially its visual practical effects, its themes, its relentless pacing and its accomplishment with genuine, lasting, atmospheric horror were recognised. The praises piled up and ‘The Thing’ by the late 90s was considered a definite milestone for horror films, one of the best ever made, and a film ahead of its time that probably ended up getting released when people were not ready for it. Today, it is one of the best known cult classics out there, and has been cited by many filmmakers as an influence on their filmmaking, the most recent one being Tarantino’s ‘The Hateful Eight’ dealing with similar themes of mistrust and paranoia.

The Ending

Theory I

They say that ignorance is bliss, but here it may also be the answer. Several of the viewers I know contended with the first and most obvious theory, complying with what was shown for the ending in the most direct form. Director John Carpenter intended the finale of the film to be completely open ended, open to interpretation. The most common one it turns out would be that after destroying the research station in an effort to eliminate the Thing, MacReady (Russel) sits by in silence drinking from his bottle, as he is shortly joined by Childs (Keith David), who claims that he went off into the storm looking for Blair, but lost him. What would be evident then according to this theory is that The Thing has apparently been eliminated, and with the camp destroyed and the ongoing storm worsening outside, the two men accept that they won’t be able to last long when the fires go out.

Tired, weary, and with nowhere to go with no means, MacReady and Childs accept their fate and share a drink, as the film ends on a somewhat ambiguous note. If it’s the other way around, and if the Thing did survive the explosion, the possibility of which I examine in the following two theories, nothing much about the ending really changes. Even if the Thing has acquired the form of either of the two men, MacReady suggests that they wait to see what happens, since the one out of the two who is still human, still not infected would want the Thing to stay where it is and not escape, accepting certain death on their own part. It is then a resignation to fate by either of the two men who knows they are still human. “If we’ve got any surprises for each other, I don’t think either one of us is in much shape to do anything about it”, MacReady says. Same R.J. Same.

Theory II

As stated in the second possibility of Theory I, wherein the Thing survives, it is very probable to assume that the only way it could have done so would be to imitate either of the two final survivors, MacReady or Childs. Now whether that happened right before the events of the ending, or somewhere between that and the blood-wire testing is highly uncertain, since it was revealed that even individual pools of blood of the Thing were enough to act independently and infect a host. Coming to the second theory that came to fore after fans pointed out certain facts, this one stems from the second possibility of Theory I itself, stating that Childs was indeed infected by the Thing, and the entity appearing in the end was infact a perfect imitation of Childs. The corroboration for this comes from the keen observation that while MacReady is continuously shivering and has his breath freezing as soon as he speaks, Childs seems to be remarkably and eerily free from that.

The second proof of the same claim, a more feeble theory, states that MacReady held out the bottle of alcohol as a test for Childs, to prove whether he was an alien or not. The men are earlier shown setting fire to the research station using dynamite sticks and Molotov cocktails. In that, it wouldn’t be completely implausible for MacReady to hold out the Molotov for Childs to drink under the guise of actual alcohol. Childs thereby drinking liquid gasoline would indeed go on to prove that he was in fact, the Thing. Ofcourse, contrary claims to rebuff the observation do exist as well, but this one observation does give one something to think about. Plus, it is as Childs put it himself, “nothing human could have made it back in this weather without a guide line”. Nothing human, indeed.

Theory III

Again, stemming from the second possibility of Theory I wherein the Thing is able to infect either of the two men, following Theory II, it would be unwise not to examine the other side of the coin. What if it was MacReady that ended up being infected and imitated following an unsuccessful escape attempt from the explosion? Makes a lot of sense too, especially since MacReady was the one to suggest that the two men “wait to see what happens”, the answer to which, we already know. The beauty of the ambiguity of the ending thereby lies in the fact that irrespective of you choosing to follow any of the theories mentioned above, you can’t completely disagree with the evidence presented in the other two.

Themes

The film primarily deals with the themes of paranoia in the face of peril and the distrust that ensues, going on to prove that in the end, humans may indeed be their own worst enemies. The film understandably stands clear of showing the virgin, untethered form of the Thing, instead choosing to showcase only part of its metamorphosis into another being, leading to the vast majority of body horror scenes, wherein the Thing emerges as a wretched disfigurement of sorts, or when it acquires the completely imitated body of the host. While this may simply be seen as an inclusion of body horror, more keen groups of audiences may choose to derive that regardless of what the Thing was or how it looked originally, this monster, sans an original identity was able to take down most of the men at the American and Norwegian stations, while it didn’t even manage to directly get to all of them.

The most notable example here would be when MacReady shot Clark in the head in a bout of self-defence, something the others termed cold-blooded murder. The film manages to maintain an atmospheric kind of horror solely through anticipation of the next attack, and more importantly, through paranoia, and the feeling that people around you may not always be the ones that they claim to be.

Final Word

For the most part, I remained terrified and disgusted throughout the film, and have no qualms in admitting that the violence and body horror, having viewed a fair share of films with it myself, was indeed a bit excessive and off putting. While I still prefer the supernatural kind of horror compared to the kind of gut sickening, body horror presented here, I have to admit that the type of otherworldly dangers presented here showed a different kind of cosmic horror, one that I wasn’t ready for. In that, as recounted in the previous section, most of the horror in the film is mined from either anticipation or the kind of dread that is induced from paranoia.

However, when ‘The Thing’ emerges on screen, it takes a different kind of breed of human altogether to not look away; it is that spiteful. Much of the work in that department, and as such the credits for the same, must go to Rob Bottin and his team who used chemicals, food products, rubber, mechanical parts, and practical puppets to bring the faceless Thing to life and making even the briefest of looks at the titular monster alien, terrifying. Ennio Morricone’s Score is another clear winner here, relentlessly pulsating in the background in the tense bits, steering clear from loud screeches or orchestral bangs characteristic of a number of scores from horror films, proving to be equally effective, if not more.

As for the final consensus on the film itself, given its critical reassessment from a different lens altogether, ‘The Thing’ would still remain the last film I would recommend to somebody, and also the last thing I would dare revisit, among the ones that I have watched recently. Then again, the film’s success is to be measured along a different yardstick probably. What if that was exactly what the film set out to do? Something to think about.

Read More in Explainers: Velvet Buzzsaw | 47 Meters Down | The Sixth Sense

You must be logged in to post a comment.