Right from the opening credits, ‘Gattaca’ promises to be a different experience. That promise partly delivers and even falters slightly in some parts, but for all its alluring qualities, I have always preferred imperfect sci-fi movies that have something new to say; something resonant, something that even mirrors the society that we currently live in, rather than perfectly polished ones. ‘Gattaca’ may not boast of the biggest budgets, and may not have the swankiest of set pieces, but it gets one thing right that is in my opinion, the core of a good sci-fi experience: a good human story.

For me, despite all the geeky science stuff about time travel, alternate dimensions and realities, and space and its vast, infinite multitude, surely getting me excited and in awe beyond what I can admit, the experience is complete only when there is a good human story, a beating heart at the core of it. That is where ‘Gattaca’ scores, telling of an undying spirit amongst the forces and structures of the man-made world holding it down, and its journey of soaring, quite literally, regardless. Along with the indomitable human spirit, ‘Gattaca’ has a setting that may as well be considered a genetic interpretation of the sociological state of things today, into the future, another potent move that makes the film stand out as a relevant sci-fi flick. However, these are only a fraction of the things this film chooses to dabble in and yet manages to emerge victorious on its merits as a film, some of which we discuss in the sections that follow. Read on.

Summary of the Plot

As the film states its timeline to be in the “not too distant future”, the world has come to normalizing artificial birthing methods, accompanied with eugenics, the science of selective genetic proliferation and birthing, and genetic discrimination. The children birthed through profiling and eliminating genetic disorders, maintaining only favourable genetic traits are termed ‘valids’, and invariably so, the ones that are a result of what we consider normal birthing without genetic pre-emption or selection are termed ‘invalids’, clearly indicating the rift between these two factions of citizens inhabiting the future world, and how the society treats them in the process. The distinction, and the discrimination both happen through biometric identification.

Other than the ‘invalids’ lacking favourable genetic traits that anyway leads to discrimination in employment opportunities against them, it is observed that they generally have a higher probability of genetic disorders and a reduced life expectancy as compared to the valids, adding to the discrimination. As a result, the valids are open to more professional and better employment opportunities while the invalids are reduced to lesser, menial jobs.

Amid the societal setup, Vincent Freeman (Ethan Hawke) is conceived normally and turns out to be one of the invalids, with his profile indicating the possibility of several frailties during his lifetime and an estimated lifespan of 30 years, 30.2 to be completely precise. His parents too consider him an aberration and plan to conceive another child through genetic selection, Anton. The competitive nature between the two is a given and the two frequently indulge in a game of “chicken” at the beach, wherein the first to return to shore from swimming in the ocean loses. While Vincent usually loses at the game, he manages to win during one rare instance, even saving Anton from drowning. Vincent dreams of going to space, something that he is repeatedly told he would not be able to achieve owing to his invalid status, but his resolve in this matter is unwavering as he soon after decides to leave his home to pursue his dream.

Vincent works several menial jobs for years in his pursuit, until finally being offered a chance to step in the shoes of a valid and pose as him to get him through the space training program. Jerome Morrow(Jude Law) is a star swimmer valid who once had a bright future before an accident rendered him a paraplegic: a rarity for valids who generally otherwise have better survival rates.

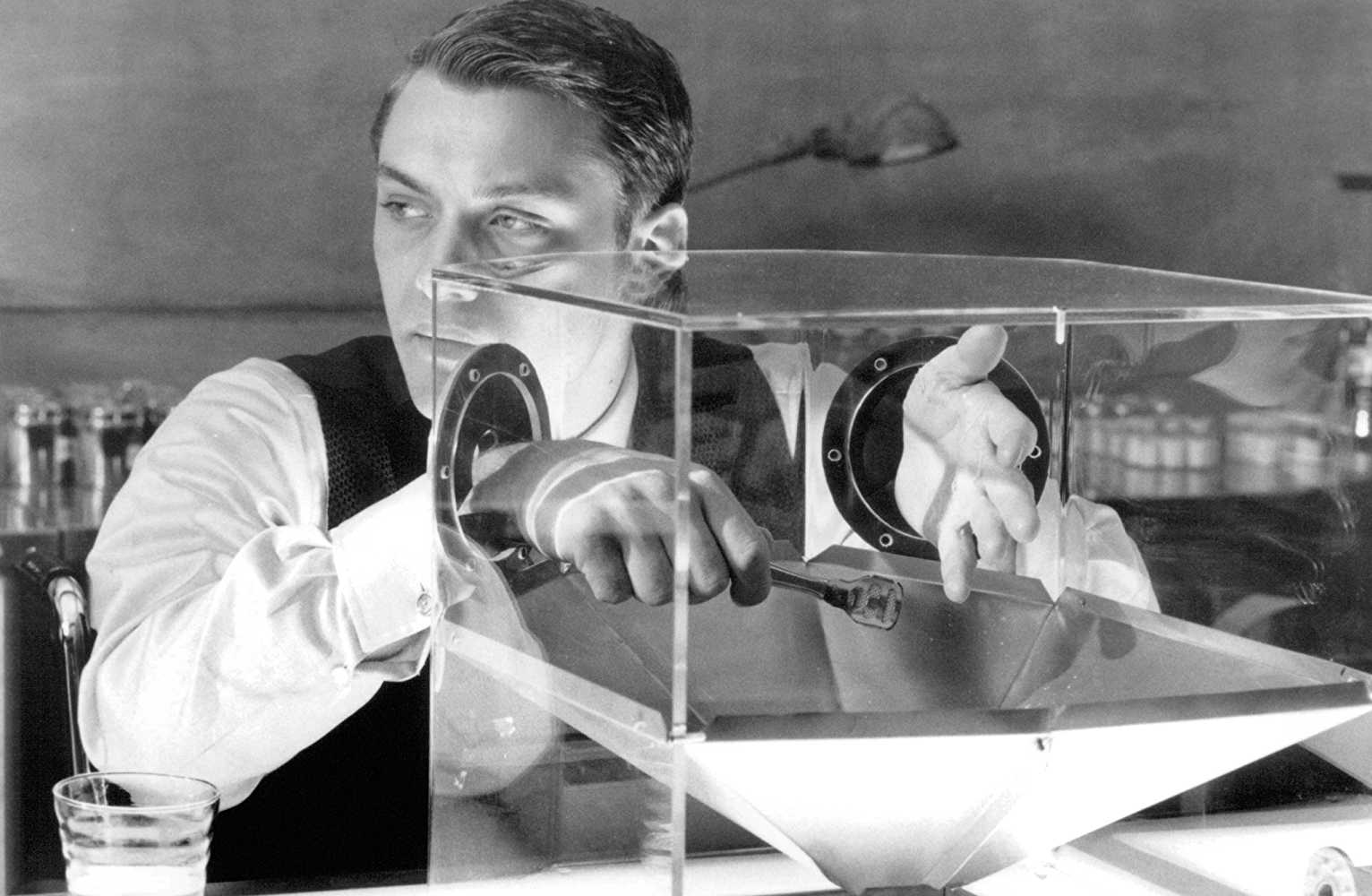

Humans called “borrowed ladders” or a “de-gene-rate” are the rare 1% of the population that get to thrive off of the DNA and identity of a fallen valid. What Vincent becomes is thus a borrowed ladder: through urine, blood, skin and hair samples from Jerome Morrow that he has to replenish daily to gain access to the Gattaca Aerospace Corporation where he now works. To pass off as Jerome for the daily biometric identification procedure at Gattaca, he even scrubs off and incinerates any of his own body hair or nails, anything that could be used to trace back to his original invalid DNA. In fact, the opening sequence is just that — stylised, blown up versions of Vincent’s daily scourings falling off on the ground.

Owing to his excellent performance at work, Vincent is due to fly out to Saturn in a week, just when his meticulously set out plan over years is threatened after one of the administrators at Gattaca is murdered, and Vincent ends up leaving one of his own original eyelashes at work, leading the police to quickly launch a hunt to find the ‘invalid’ Vincent, now working in Gattaca under the guise of Jerome. Among a budding romance that develops between him and Irene (Uma Thurman), a fellow co-worker who is at a higher risk for heart failure despite being a valid, and the real Jerome acting increasingly erratic as the launch day comes closer, Vincent narrowly dodges the police’s attempts at closing in on him as the murderer due to the eyelash discovered at the murder site. He even learns that Jerome himself was the reason behind his current state: he threw himself in front of a car when he realised that he could not always win despite being “designed” to be the best.

The investigation comes to fruit when it is revealed that it was indeed the program director at Gattaca who committed the murder for fear of his program being cancelled. Vincent is left off the hook, but quickly realises the investigating officer was indeed his own brother, Anton, who confronts him regarding the illegality of his actions, having figured out what Vincent was up to with Jerome’s fake identity.

Despite the heated confrontation, Vincent maintains that he got where he was based on his own merits irrespective of his fate being predestined by genetic profiling, and the two decide to go head to head in a final competition of ‘chicken’ at the beach. Vincent is able to beat Anton after a lot of relentless struggle, leaving Anton surprised at his skill and stamina, while Vincent reveals the real reason he won was that he didn’t save any energy for the swim back, which is a wonderful allegory, to be explained later in the next section. While Anton begins to drown, Vincent saves him and uses the stars to find his way back to shore along with him.

Ending Explained

‘Gattaca’ is essentially encompassed as a story within the seven days following which Vincent is to be a part of his first manned mission to Titan, Saturn’s moon, after years of toil, even though it regularly dabbles between the past to reveal more about what the planet has become in the not too distant future, and what got Vincent where he was currently. In that, it is suffice to say that the ending can be construed as enveloped in the final day: the day of the launch.

As both Jerome and Vincent reminisce on what their journey together has been, and Vincent confronts Irene about his reality, the hour of the launch nears as Vincent readies himself for the fruition of a dream borne life long. Before leaving, Jerome shows Vincent that he had stored enough blood and urine samples for Vincent for when he returned, despite Vincent stressing that he won’t need it any where he was going. He hands him an envelope and asks him to open it only once up there. Just as he is about to board, unexpectedly so, he is asked to go through one final screening test, which he knows he is bound to fail since he didn’t have any of Jerome’s samples with him at the moment.

Fearing facing his fate, he hands over a urine sample to Dr. Lamar, who it is then revealed had been aware of Vincent posing as a valid all along. He tells Vincent that his son looked up to him because he too hoped to be someone greater, since despite being valid he wasn’t “all that they had promised”, before passing Vincent off as a valid and allowing him to board.

As Vincent looks on towards Lamar in gratitude, he boards the spacecraft along with his fellow astronauts, while at the same time as ignition, Jerome commits suicide by immolating himself in the incinerator while wearing his silver swimming medal, leaving there to be only one Jerome, just as he had thought — for his name to live along regardless through Vincent. When finally in space, Vincent opens the envelope to find a lock of hair from Jerome attached to it, as a sign of his DNA identification, might he need it while up there. The selfless act makes Vincent muse that “for someone who was never meant for this world, I must confess, I’m suddenly having a hard time leaving it. Of course, they say every atom in our bodies was once a part of a star. Maybe I’m not leaving; maybe I’m going home.”

As mentioned earlier, the ending also holds a beautiful allegory with respect to the kind of people Jerome and Vincent were. As with the “chicken” races with his brother, Vincent was a man with unrelenting focus for his dream of travelling to space: we see him seldom slipping in his pursuit and his demanding daily regime of embodying Jerome in almost every way possible for years at end, while Jerome frequently acted out erratically and irresponsibly, having nothing to lose, and yet showing the ultimate act of selfless towards the end. It is almost as if Vincent had something personal against the system for letting him down all those years, like he has to prove something to himself and to everybody out there who was bogged down by the inadequacy of the genetic system that labelled them as an ‘invalid’.

However, Vincent, despite being committed to a cause, reveals something key to his character arc in the final bits of the film, notably when he is indulging in a game of chicken with his brother one last time. He reveals that his secret to winning that bout was that he didn’t save any for his journey back. I wouldn’t necessarily call that short-sightedness, but he was so driven in his pursuit that he gave it his all in winning it, without much thought or consideration for his way back, be it in realising his dream of travelling to space or a simple game of chicken with his brother, both of whom harboured a bittersweet relationship with each other since the beginning owing to the genetic superiority of the other.

For him, victory had always been a one way journey, also reflected in when he terms his journey to space one for his new home. Jerome, apart from literally giving him a new lease on life, broadens his perspective on it being a two way journey, imbuing him with the tools to do so too, albeit in a heartbreaking act of sacrifice. I see it as Jerome’s redemption after leading a bitter life in the wake of his realization: the completion of Vincent’s purpose in life lends HIM purpose after he realised his predestined one wasn’t any good. A beautiful allegory, indeed.

Themes

I believe that no good sci-fi movie has ever existed solely on the basis of fantastic concepts, for they gain real ground only when they begin to reflect or spin on existing social conditions. For example, a story on a dystopian future would never be as alluring until it actually extended a current scenario and extrapolated it into the future. Likewise for ‘Gattaca’, its win is its sociological relevance mostly stemming from its high concept of genetic profiling and identification, the world in the film almost entirely running on it. In the modern world where discrimination is common on one of countless grounds, ‘Gattaca’ extends it into the future where discrimination exists not in colour, creed or sex, but in the very basest of bits of what makes us organisms to begin with — genealogy. Come to think of it, what could be pettier than discriminating against somebody with a perceivably inferior set of, cells? It is oddly funny yet starkly alarming, since in all its probability, it didn’t seem too farfetched.

To add to it, not much unlike one of Ethan Hawke’s other excellent films, ‘Predestination’. ‘Gattaca’ too deals with the idea of everything being predestined and what merit it holds. While the former resented in giving a clear answer, ‘Gattaca’ seems to have one just as Vincent breaks the wheel while Jerome comes under it. With all the chatter about valids and invalids and Vincent’s lifespan being limited to roughly 30 years, declared at the time of his birth, he defeats those notions and achieves what he set out to through sheer tenacity of his vision, leaving nothing to the viewers imagination in how predestined his fate was.

Finally, I consider ‘Gattaca’ to be a fairly inspiring movie as well. It has no dearth of emotional moments, and most of them courtesy of its central protagonist in Vincent. It is true what they said of stubborn souls and the universe falling in love with them. The realisation of his dream of space travel was as much his victory as it was for Jerome, Irene, Dr. Lamar, even his son, and virtually everything in the universe that aligned perfectly to make it happen.

Final Word

‘Gattaca’ may not be a perfect movie, but it is still one of the few sci-fi movies from the 90s that still holds up, not to mention being consistently engaging, despite a number of subplots that all have something to add to the pivotal narrative. Its premise may not be ingenious even for its time, especially as compared to now when there is no dearth of movies about the same kind of genetic profiling and predestination eliminating free will. But ‘Gattaca’ finds relevance in telling a human story first with the sci-fi as the backdrop. I can surely understand its unlikely cult appeal, and while it is a shame it bombed when it first released, it will always continue to have a revered place in my DVD collection, as it should in yours.

Read More in Explainers: Total Recall | Life of Pi | Terminator 2: Judgement Day | Jacob’s Ladder

You must be logged in to post a comment.