Directed by John Madden, ‘Operation Mincemeat’ is a gripping war drama movie. Set amidst World War II, it follows the Allies as they try to undo Hitler’s occupation of Europe. To fool the invading German troops from the Allied Invasion of Sicily, two British intelligence officers devise and execute a brilliant ploy to disguise a corpse as a naval officer and strategically plant it to be discovered by the enemies. However, they must tread carefully to outwit the Germans and execute their plan before time runs out.

The elaborate narrative and characters are brought to life by the compelling cast performances led by Colin Firth and Matthew MacFadyen. Moreover, the realistic backdrop makes the audience wonder if the film is based on an actual event in history. So, if you too are curious to find out, you’ve found an ally in us. Let’s dive in!

Is Operation Mincemeat Based on a True Story?

Yes, ‘Operation Mincemeat’ is based on a true story. It is adapted from Ben Macintyre’s eponymous book about the real Operation Mincemeat, a brilliant 1943 deception operation planned and executed by British intelligence. It was conceptualized to divert the German troops’ attention from Operation Husky, in which the Allied powers planned to invade and take the island territory of Sicily away from the Axis powers.

The inspiration for Operation Mincemeat came from the 1939 Trout Memo issued by British naval intelligence director Rear Admiral John Godfrey. The document outlined numerous schemes and suggestions on how to lure the German submarines and ships into danger zones to defeat them. On this list, the 28th point suggested misleading papers being planted on a corpse to be discovered by the enemies.

However, Macintyre suggested in his book that the memo looked more to be the work of Godfrey’s personal assistant Lieutenant Commander Ian Fleming, who later went on the write the James Bond series of spy novels. Following an aircraft crash off the coast of Cádiz, Spain, in September 1942, the British intelligence deduced that despite being neutral, the Spanish were passing on obtained information to the German intelligence group Abwehr.

Thus, Charles Cholmondeley, the secretary of the double agent intelligence team Twenty Committee, devised his own version of the above-mentioned suggestion in the Trout Memo. As per Cholmondeley’s plan, the lungs of a dead body obtained from London hospitals would be filled with water, and crucial documents would be planted in the inner pocket of the garments. This would ensure that when the body was discovered by enemies, they would believe the person’s aircraft was shot down.

Since the Twenty Committee was skeptical of Cholmondeley’s plan, chairman John Masterman assigned naval representative Ewen Montagu to work with him on developing it. The latter was working at the Naval Intelligence Division under Godfrey at that time and had been briefed about the relevance of the deception operation.

Montagu and Cholmondeley worked with MI6 representative Major Frank Foley to refine their strategy. With the help of a pathologist, they concluded that the lungs of the corpse did not need to be filled with water, as the Spanish were averse to post-mortems. On January 28, 1943, coroner Bentley Purchase from the Northern District of London contacted Montagu and provided him with the corpse of Glyndwr Michael, a Welsh homeless man residing in London, who had died after ingesting rat poison.

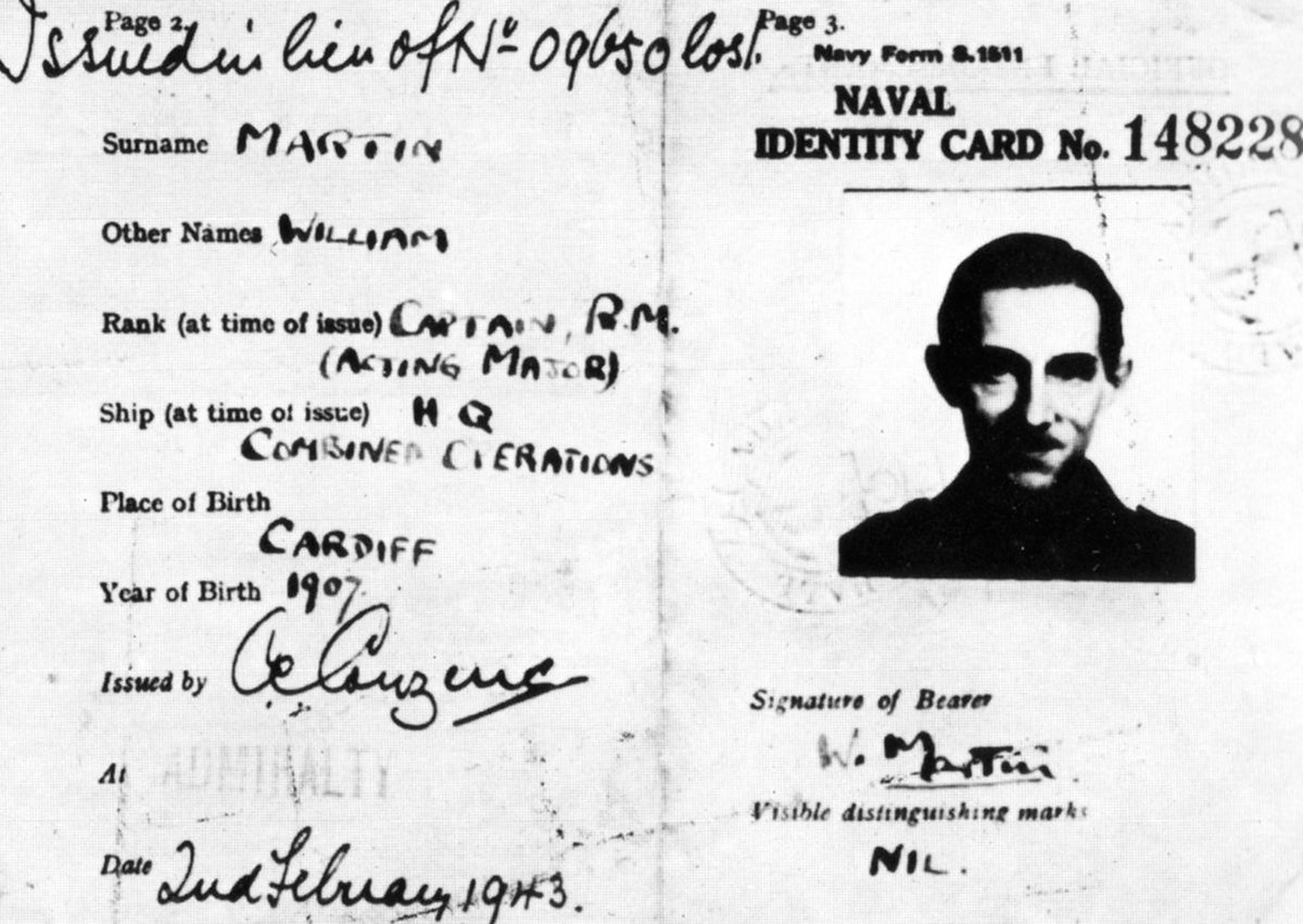

Michael was given the fictitious identity of Captain (Acting Major) William Martin of the Royal Marines, assigned to the Combined Operations Headquarters. However, it was not until the 1990s that his real identity was revealed to the public. The name William Martin and the assigned rank were common during those days in the Royal Marines and thus, were chosen to make the corpse’s identity generic and not easily verifiable. Moreover, his rank made him eligible to carry sensitive documents but not be a known face.

In addition, documents such as the photograph of a fictitious fiancée named Pam, letters from her and Martin’s father, an engagement ring receipt, and other such papers written with ink that would last long in seawater, were planted in the corpse’s pockets. Not just that, a lodgings bill, theatre ticket stubs, a book of stamps, cigarettes, and keys, among other things, were added to establish Martin’s presence in London in the days preceding his death.

MI5 member Captain Ronnie Reed was photographed for the identity card, as he bore the closest resemblance to Michael’s face. Montagu and Cholmondeley then spent the next few days wearing the uniform and the identity card to give them a used look. For the main top-secret document, Lieutenant General Sir Archibald Nye, the vice chief of the Imperial General Staff, helped by providing a letter in his handwriting, as devised by Montagu.

Addressed to General Sir Harold Alexander, commander of the 18th Army Group in North Africa, the letter clearly stated that Sicily was a secret cover-up of the plans to invade the Balkans and dismissed it as the main target of the operation. An introduction letter for Martin from Vice-Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten was also enclosed in the documents, and a single black eyelash was placed in the letter to later ensure whether the Germans or Spanish had opened it. The documents were further put in a briefcase, and it was attached by a leather-covered chain looped around the corpse’s trench coat.

Taking into account the tides and currents as well as the presence of German intelligence agent Adolf Clauss in Huelva, Spain, it was chosen as the location where the body would be placed. Furthermore, it was decided that a submarine would be used as the mode of transportation for practical reasons. The plan eventually got approved by both Prime Minister Winston Churchill as well as Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower. On April 17, 1943, the corpse was prepared and transported to Greenock, Scotland, and taken aboard in a preservation container in the submarine HMS Seraph.

Finally, in the early hours of April 30, 1943, the corpse was released into the water, off the coast of Huelva. The preservation container was destroyed later at a distance, while the body of “Major Martin” was discovered by a local fisherman later that morning. The Spanish soldiers carried the corpse to the naval judge in Huelva, and British vice-consul Francis Haselden was informed as well. He was secretly a part of Operation Mincemeat, and hence he ensured that the corpse was buried with full honors, without an autopsy.

Haselden also sent out some pre-scripted telegrams to his superiors, which the British knew were being intercepted by the Germans. As soon as the news of the documents found with the corpse reached the Abwehr agents, head Admiral Wilhelm Canaris pressured the Spanish to surrender the briefcase, and the information carefully taken from the letters was relayed to the Germans. On May 11, 1943, when the briefcase was returned to London via Haselden, forensic examinations and the missing eyelash proved that the Germans had tampered with the documents.

Three days later, on May 14, 1943, a German communication was decrypted by the Ultra – a signal intelligence unit – which indicated a warning of the Balkans being invaded. Hence, Hitler got convinced that Sardinia and the Peloponnesus were the main point of interest for the British, and he and Mussolini employed a majority of their troops to secure Greece, Sardinia, and Corsica.

On July 9, 1943, the Allies invaded Sicily under Operation Husky, and due to a lack of German reinforcements, they were victorious. Given its huge success, Operation Mincemeat is considered to be one of the smartest war strategies in World War II history. Several books and plays on the same have been created.

In a May 2022 interview, director John Madden shared that the story was not much heard of while he grew up in England. But Ben Macintyre’s book and several declassified MI5 files brought the story into the limelight. “It’s one of those stories [where] you kind of think, ‘Really?!’ as you’re going into it,” he said. Madden continued, “The strangeness and the oddity of it and the sort of playfulness of it is an odd point of entry to a World War II movie… and more fascinating, of course, because it’s true.”

However, some portions of the movie have been slightly exaggerated for entertainment. Thus, we can say that ‘Operation Mincemeat’ is mostly an authentic portrayal of an incredible true event and honors the efforts of those involved in the actual operation.

Read More: Where Was Operation Mincemeat Filmed?

You must be logged in to post a comment.