‘Wicked Little Letters,’ the delightfully profane film set in 1920s England, follows the story of two women who find themselves in the middle of a postal scandal that incites much outrage within their community. After Edith Swan, a model Christian woman, starts receiving obscene letters filled with abuse, suspicions inevitably fall on her former friend, Rose Gooding, an Irish migrant woman known for her rowdy behavior. Despite the latter’s persistent denial of penning the abusive letters—which quickly spread out to the entire town—Rose faces legal troubles for the accusations.

However, as the case is taken to court, one female police officer, Gladys Moss, instigates a non-official investigation with Edith as her primary suspect. Therefore, as the truth emerges about the woman’s involvement in the composition of letters that grossly insult her own character, it leads to a natural line of questioning regarding her motive behind the perplexing endeavor. SPOILERS AHEAD!

Edith’s Desire for Societal Approval

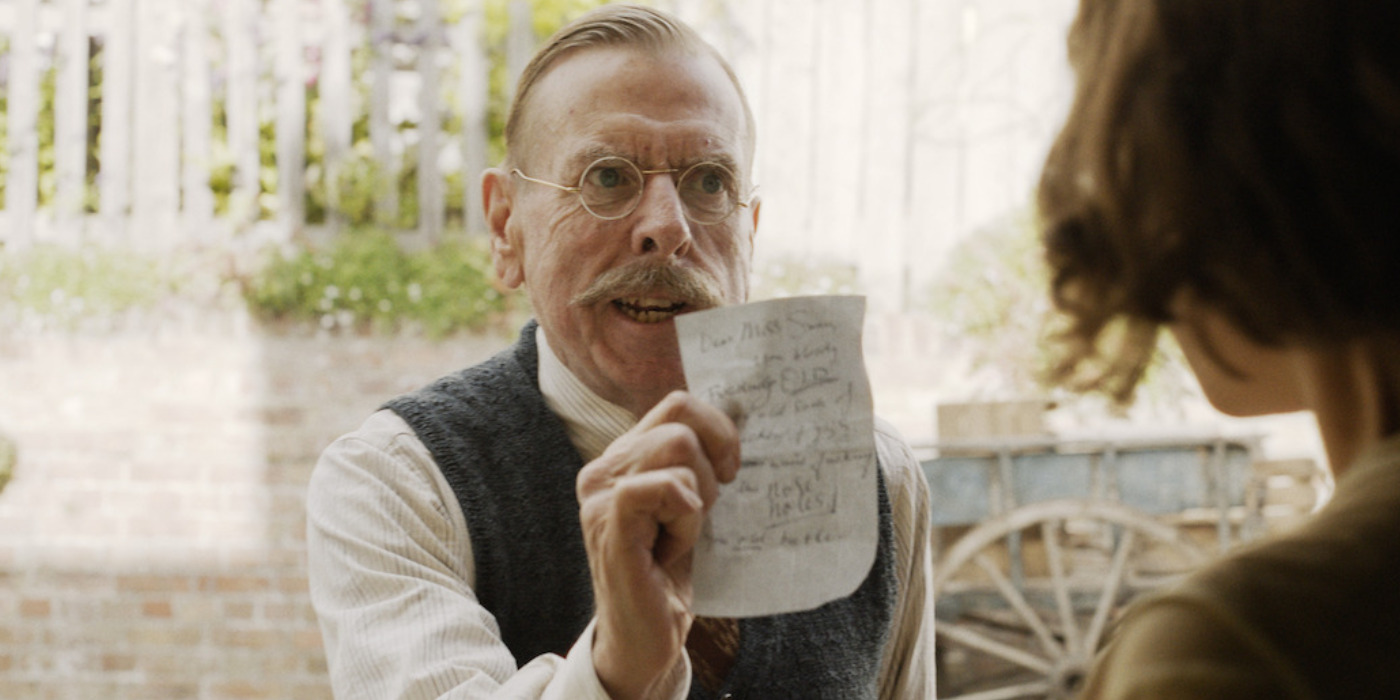

In many ways, Edith Swan’s character forms the story’s epicenter, with the complex motives behind her actions holding the narrative together. One of the defining traits about the woman—that even she herself holds close in her sense of self—is her identity as a good Christian woman. Even when her father, Edward, reports the letters to the local police, she remains unwilling to make broad assumptions about others’ characters, reciting Bible verses to establish her own virtues. Consequently, from the get-go, Edith’s ability to rise above the circumstances sheds a positive light on her person. The same cements her as a stark contrast to the person penning vulgar letters to her.

However, a shift occurs after Edward righteously accuses their neighbor, Rose Gooding, of sending his daughter the hate mail. The scandal breaks out to a higher magnitude, inviting town-wide attention, if not from the entire country. Newspapers begin publishing articles about the incident, painting Edith as a martyr for her ability to remain level-headed and gracious in the face of Rose’s gasp-worthy written abuse. As such, Edith finds herself receiving an onslaught of positive recognition where people sympathize with her as a victim, showering her with proverbial pats on the back.

Therefore, once the narrative revelation arrives that Edith has been penning the abuses to herself, it contextualizes her hopeless need for such public praise. Her entire life, she has been the model, upstanding woman that society and her father have told her to be. Thus, she’s quiet, obedient, and disciplined as can be. Even so, despite meeting the standard, happiness, and satisfaction have somehow evaded her. Conversely, Rose is entirely untamed and free to be whoever she wants to be, even if it might invite society’s scorn and ire.

Witnessing the contrast between her situation and Rose’s fills Edith with frustration since she’s unable to see why the former is so much more fulfilled in her life, even after going against every convention. Consequently, Edith’s foray into penning the abusive letters addressed to herself stems from her need to have others affirm her morality and righteousness. In becoming a victim of the letters, Edith finds a surety that her restraint and conformity will be awarded. Although she doesn’t set out to incriminate Rose for these letters, the blind faith others have in her word against the other woman further pronounces the same, compelling her to continue writing the letters.

Edith’s Act of Rebellion Against Her Jailer, Edward Swan

While Edith’s actions are undeniably fuelled by her need to be heroized by society as a virtuous woman, her familial relationships may have also played a vital part in her narrative. Edith is a fully-grown adult woman who still lives with her parents, living by her father, Edward’s rules and whims. Since her engagement fell through, she has been trapped inside her maiden house, forced to comply with chores and punishments in a state of perpetual infantilism. Although she never complains about the same, her vexation against her father remains evident. As such, once the narrative witnesses the woman authoring another crude letter to herself in the wake of her father’s chastising—a link forms between the two ideas.

Part of Edith’s motivations in writing those letters emerge from her indignation with Edward, who constantly keeps her imprisoned under his control. His need to keep his daughter chained to him becomes evident with the revelation that Edward drove Edith’s former betrothed, Sidney, away to steal the woman’s opportunity to escape his household.

Edward establishes himself as an upholder of expectations for women to comply with his version of propriety from the start. Therefore, it is no surprise that he wishes to keep a lifelong subordinate under his authority. Within the same power structure, his daughter finds the anonymous foul-mouthed letters as a fit outlet for her anger that comes with the added benefit of agonizing her father. For the same reason, when he attempts to assure Edith that he will find a way to bring her back from prison, the woman blows up at him in a storm of vocal profanities—finally placing her fury towards the source of her grievances.

The Reality of Edith Swan and Her Poison-Pen Letters

‘Wicked Little Letters’ dramatizes the real-life stories of Edith Swan and Rose Gooding, who were entangled in a near-identical scandal in the 1920s. In translating the tale to the modern cinematic medium, the film adopts certain creative liberty that allows the narrative to mold the tale to complementary themes of social messaging. Consequently, the changes made to reality allow for Edith Swan’s on-screen character to embody concepts that lead to a well-rounded and nuanced story about the ugly outcome of women’s societal oppression. However, in reality, Swan’s actions were a lot less easy to stomach, and her motivations a lot harder to understand.

Unlike her cinematic counterpart, Swan was much more intentional in framing the real-life Rose Gooding for the vulgar letters. In fact, she even signed some of the letters off with “R,” “R.G.,” or even “Mrs. Gooding’s compliments.” Moreover, the gravity of these letters expanded even further than simple insults—with some letters calling for people’s unemployment and fabricating stories of Swan’s pre-marital pregnancy. Thus, in reality, Swan’s motivations behind writing the letters came with the evident intention of falsely incriminating Gooding rather than any cravings for martyrdom.

As per historical records, Swan sported a feud with Gooding over neighborly issues. However, the real spark behind the former’s hate-mail plan arrived in the Spring of 1920, when she overheard an argument at Gooding’s house decorated with profanities and obscene language. Reportedly, the argument was born out of Gooding suspecting her husband, Bill, of having an affair with her sister, Ruth, who also lived with the couple. Consequently, Swan called the authorities on her neighbor. Her complaint consisted of an unfounded report that Rose Gooding had beaten Ruth’s newborn baby.

In the aftermath of the same, Swan penned her first letter. As such, in reality, the woman’s actions were more driven by her contempt toward Gooding than any introspective conflict. In fact, many of the instances that bestow nuance upon the film’s iteration of Edith weren’t true for the real Swan. In real life, Edith Swan wasn’t the only one of her siblings to live with her parents and was actually responsible for the end of her own engagement as a result of her letters. Thus, the film’s adoption of Edward Swan as its subliminal antagonist emerges without basis in reality. In fact, during the time of Swan’s actual conviction and in the years that followed, many have speculated about her mental stability, citing mental illness as a possible reason behind her actions. The fact that she was enrolled in Worthington’s East Preston Institution by 1939 further supports this theory.

Read More: Best True Story Movies on Amazon Prime

You must be logged in to post a comment.