There is a running joke in Hollywood that unless an actor portrays God or his theological counterpart, he can’t be considered a legendary thespian. Perhaps the same thing can be said about filmmakers and their desire to make movies about Tinseltown. From ‘Tropic Thunder’ (2008) to ‘La La Land’ (2016) to ‘Once Upon A Time…In Hollywood’ (2019) – there have been quite a few projects in recent years that have explored various facets of the show business.

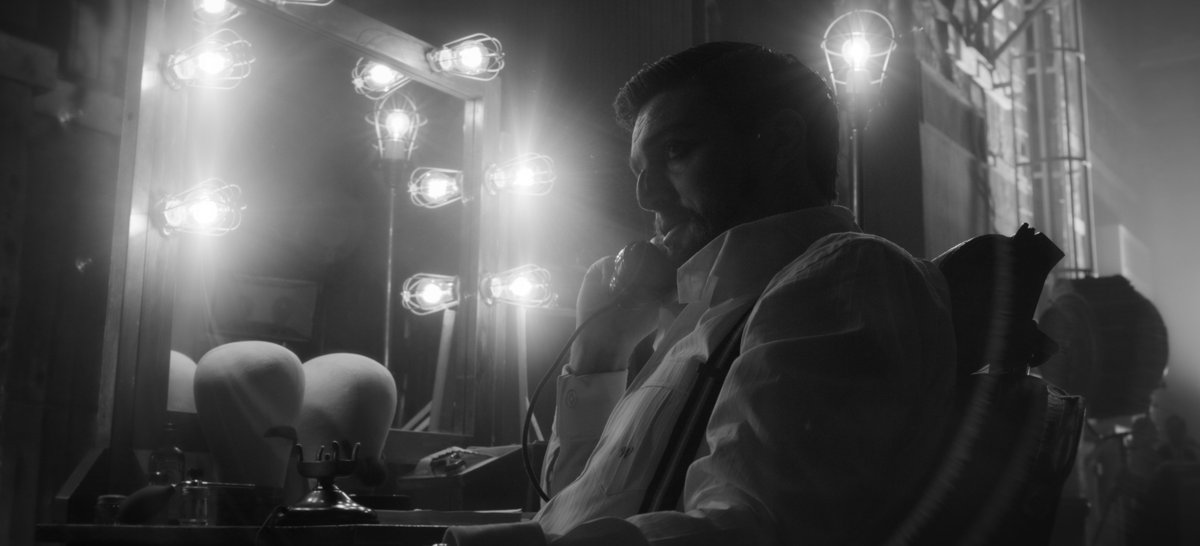

What sets ‘Mank,’ David Fincher’s black-and-white retelling of how the script for ‘Citizen Kane’ (1941) was written, apart is how intimidating the task must have been. This is Fincher’s second biopic after ‘The Social Network’ (2010). Although he doesn’t have Sorkin’s blazing dialogues set the stage for him in this film, he has his late father’s quiet tenacity and an odd camaraderie that Fincher Sr. must have felt with the criminally under-appreciated screenwriter whom the movie follows. SPOILERS ALERT.

Mank Plot Synopsis

While recuperating in a hospital after a car accident in 1940, Herman J. Mankiewicz (Mank for short) (Gary Oldman) is visited by 24-year-old Orson Welles (Tom Burke) with an offer to write a script for him on his experience with William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance), the biggest media mogul of the time. Called the “Golden Boy of Radio” by some of his detractors, Welles has secured an unprecedented contract with RKO Radio Pictures for his debut feature that allows him absolute freedom on the project without any studio oversight.

He can hire any scriptwriter he wants and picks Mank for likely two major reasons: he was once part of Hearst’s inner circle, and his reputation as a ghostwriter. Over the years, Mank has worked on a number of scripts, including ‘The Wizard of Oz’ (1939), originally penned by other writers. However, he didn’t receive any credit for many of them. The initial deal between him and Welles is similar in principle. He will write the script, and Welles will get the credit for it. He knows that there will be a backlash, which probably plays a significant role in him accepting the deal.

Welles moves a still-injured Mank to a quiet Victorville ranch so he can write without any possible distraction, which includes his family, his writer friends, gambling, and alcohol. Mank has a typist, Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), and a nurse/housekeeper, Fräulein Frieda (Monika Gossmann), to keep him company at the ranch. Welles also sent John Houseman (Sam Troughton), a theater personality and long-time collaborator of his, to babysit Mank and ensure that he stays away from alcohol. Houseman also serves as the script editor.

The film oscillates between the time Mank wrote the script and the time when he interacted with the people who inspired the characters in the script between 1930 and 1937. It demonstrates in vivid detail what prompted him to write such a script. Rita immediately recognizes that Charles Foster Kane has been modeled after Hearst and Mr. Bernstein after Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard), one of the co-founders of MGM. However, Mank disagrees that he based Susan Alexander Kane on Hearst’s mistress Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), and goes on to maintain that to be true till the end.

Mank Ending

There are 11 flashback sequences in the film, working in tandem with the main plotline to give the story a sense of completion. In 1930, Mank is still working for Paramount when Charles Lederer (Joseph Cross) walks into his office. Later, he invites him to accompany him as he goes to see his aunt. His aunt turns out to be Davies, through whom Mank meets Hearst. Mank’s quick wit and self-deprecating humor quickly win over Hearst, and he becomes part of their inner circle. Hearst is one of the most powerful and influential men in the world.

So, the gatherings he and Davies host, attract some of the biggest stars of Hollywood, from Charlie Chaplin to Greta Garbo to Clark Gable. As some of these flashback scenes are set at the height of the Great Depression, it has become a hot topic of conversation in these parties, along with the rise of Hitler in Germany. For Mayer and some of the others, there is a correlation between European communism and the Socialist platform on which Upton Sinclair (Bill Nye), an author and Democratic candidate, is contesting in the 1934 California Gubernatorial Election.

Based on an offhanded suggestion from Mank, in which he tells Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley), a top executive at MGM, that if the studio can convince people that “King Kong is 10-story tall and Mary Pickford is a virgin at 40”, they can make them believe anything. So, the studio launches a highly effective video propaganda campaign against Sinclair and his policies. It ultimately led to his defeat and the election of Frank Merriam as the Governor of California, an outcome that the studio heads at MGM desired.

Mank learns that Hearst financed the propaganda drive. His friend Shelly Metcalf (Jamie McShane), whose personal views are similar to that of Sinclair, was lured into making the project with the prospect of directing it. His subsequent suicide plays a vital role in Mank’s later outburst. He is painfully aware of his role in Sinclair’s defeat, but unlike Metcalf, he finds solace in his two biggest vices – gambling and drinking.

The Four Visits

Despite what Welles believes, sobriety doesn’t help Mank’s writing process. If anything, he falls behind schedule. It is when he starts drinking again he writes as if he is possessed and finishes the script within the deadline. Houseman is quite happy with the script, and so is Welles. They know the storm that is bound to come and brace themselves for it. Mank invites Lederer to come to the ranch and read the script.

Almost understandably, Lederer is upset, especially about what he believes to be a horrible portrayal of his aunt. Despite Mank’s insistence that Susan is not modeled after Davies, he just doesn’t believe him. When Lederer leaves, he takes the manuscript with him. It is heavily implied that the manuscript will circulate among all the interested parties in the next few days. When Mank’s brother Joe (Tom Pelphrey) visits him, Hearst and Mayer have already begun efforts to suppress the film. Although Joe criticizes his brother for the script, he admits that he thinks that it is his best work.

For Mank, who has begun to consider himself as washed-up, this is a validation of him as a writer. By the time Davies visits, he has realized that he has to see it through. They part ways with a promise that they will not hold each other responsible for whatever the movie’s fate ultimately is. The fourth and last visitor is Mank’s long-suffering wife, Sara (Tuppence Middleton). Throughout the film, he asks her multiple times why she is still with him.

Considering how self-destructive he is, it’s a valid question. In the last act, she finally answers: she wants to see how it eventually ends. Being married to Mank had been many things, but it has never been boring. She knows that it doesn’t matter what she thinks about the manuscript, as he will do what he thinks is best. However, she does make one demand. She refuses to be called “Poor Sara” any longer, a nickname that she received because of her husband’s eccentric behavior. By forcefully disassociating from it, she reclaims agency in her own identity.

Don Quixote and Organ Grinder’s Monkey

The film’s climax takes place in a flashback. On a night in 1937, Mank attends a dinner party at Hearst’s home in Sam Simeon, utterly drunk. Still burdened by Metcalf’s death, Mank launches into a passionate and biting monologue in which he compares Hearst to Don Quixote, Mayer to Sancho, and Davies to Dulcinea. As Quixote tilted at the windmills, the imaginary targets, Hearst built up a grand media empire through muckraking journalism. But that was clearly not enough for him.

Seeking public adulation, Mank joined politics, but not before embracing left-wing ideals because he concluded that the only way a wealthy man can get poor people’s votes is by accepting socialist ideals. By the time his career as a politician fizzled out, the Sancho of the story had set up another kingdom in the entertainment industry. This is when Davies’ Dulcinea entered the tale. Considering the similarities between ‘Citizen Kane’ and this modern makeshift rendition of ‘Don Quixote’ by Mank, it’s safe to assume that the latter ultimately becomes the rough first draft of the former.

When Mank accuses Hearst of ruining Sinclair’s chances during the election because he reminded him of who he used to be, Mayer lashes out and reveals to Mank that Hearst pays his salary through MGM, and not because of what he writes, but what he says. At that moment, Mank finally comes to understand the role he has served in these gatherings all these years: that of a court jester. As Hearst leads Mank out of his home, he tells him about the parable of Organ Grinder’s Monkey, reminding him of his place.

According to Hearst, Mank might think that he has control over his own actions, but he has been performing to Hearst’s whims for a long time. His self-importance is tragically based on an erroneous conclusion. The world in which Mank resides is ruled by Hearst. The very notion that a delusional monkey can rebel against the man that holds its chain is laughable. Three years after this incident, Mank agrees to Welles’ proposal.

The Oscars

When Welles arrives to inform Mank that he is not required for the rewriting part, he has already come to acknowledge that this manuscript is his magnum opus and demands credit for it. He reminds Welles that although the Hollywood insiders think he is a nuisance, they downright hate Welles. As an outsider, he needs as much help as possible because this will be an uphill battle. While Welles recognizes the truth in that statement, he still throws the liqueur cabinet against the fireplace.

This ends up inspiring Mank to write the scene where Susan leaves Kane. As his wife has done with him, Mank has decided to stay on the course and see where it ultimately leads. Despite all the hurdles that Hearst and Mayer put before it, ‘Citizen Kane’ is released in 1941, with Mank and Welles sharing the writing credits. The movie gets nominated for nine Academy Awards and wins in the Best Writing category. Neither of them is present at the ceremony.

After Mank’s name is announced, applause drowns the presenter, who says Welles’ name. As he makes clear in an interview, Welles believes that there was a Hollywood bias at play with how ‘Citizen Kane’ only won in the category in which an insider was nominated. During his acceptance speech, Mank asserts himself as the sole writer of the script.

The antagonistic relationship that has evidently developed between them will last for the remainder of Mank’s life; he passes away in 1953. He never collaborates with Welles again, nor does he churn out another original screenplay. Despite the success, Mank remains as self-destructive as ever. By his own admission, he builds up a metaphorical cage around himself after winning the Oscar and keeps himself inside it until his death.

Read More: Is Mank a True Story?

You must be logged in to post a comment.