Slow Cinema, in title at least, is an inherently unattractive proposition. A lot of contemporary film-making in Hollywood is obsessed with constant involvement of the audience even to go so far as forcing in inept exposition and contrived plot-points to keep the pace intense. As a result, the movies below may be difficult to stomach at first for big fans of Western blockbuster fare but they are not inaccessible: Slow cinema is also a uniquely special form of expression that allows its audience to breathe and soak in the world its directors are creating, often making for far more vivid, contemplative experiences than shorter movies could manage.

I’ve decided to exercise a one film per-director rule for this list, given the fact that many film-makers who specify in slow cinema are able to practice and refine their skill in order to create a dominant body of work that would overwhelm the less specifically committed filmographies of other directors. Also, it’s a nice way to be introduced to several artists who take this lesser trodden path and gives new viewers options on where to start. That being said, here is the list of top slow cinema movies ever.

10. Close-Up (1990)

Iranian legend Abbas Kiarostami left an undeniable gap in the medium when he passed on last year- though his body of work will survive ad-infinitum. Classics like Through the Olive Trees, Taste of Cherry and the more recent Certified Copy are all firm examples of his slow-cinematic craftsmanship but this 1990 doccu-drama that assembles the same people who were involved in a fascinating true story of art and interpretation and re-enacts their court case with a beautiful use of time to capture otherwise mundane moments and in focusing on them impart an importance that forces you to pay attention and, just maybe, foster the same blissful basking in our world that Kiarostami’s characters strive to achieve. Capped off by a wonderful ending and driven by incisive discussions on the nature of art and how it relates to the cinema and both those people who pay to sit in front of the screens for hours at a time and the ones behind the camera creating for them — Close-Up is essential cinema and a steady introduction to the longer, more challenging works later down this list.

Read More: Best Twist Ending Movies of All Time

9. L’Eclisse (1962)

Famed Italian auteur Michelangelo Antonioni makes extremely difficult films. What I mean by this, far removed from the extensive run-times and long takes of other works on this list, is that he purposefully chooses to focus on ennui: Alienation and loneliness and longing that takes hold of the human psyche and forces an invisible wall between them and everyone else. Naturally, such a mental process is difficult to film and is perhaps far better suited to the internal monologue of a book- but that is why L’Eclisse (and Antonioni’s greatest, if not slowest success in the fantastic Red Desert) is so worthy of praise. It tracks through the ruins of a relationship through to another one whilst never quite catching the slopes of any plot-point, refusing to slide down and commit to a singular strand of narrative. Instead, we get a structural reflection of the way lead Monica Vitti is feeling throughout- an ingenious narrative design that engages with its brief dives into story and fascinates with careful observation of her decaying mental health. The closing moments of L’Eclisse are what really carve out its place here, however, with a perfectly ‘slow cinema’ culmination of everything the movie has covered in a way that fully realises the potential of a movie over the aforementioned novel by visualizing ennui. Somehow, someway, Antonioni did it — and despite his faults I’ll always admire him for being able to make nothingness tangible to the human eye.

Read More: Best Movies With Strong Female Leads

8. A Brighter Summer Day (2011)

Edward Yang’s equally acclaimed Yi Yi left me a little sore with its endless strands and lack of central motivation but the balance Yang struck 9 years earlier with this 237 minute A Brighter Summer Day signifies a man at the peak of his powers with full understanding of the possibilities such a story can achieve. Slow Cinema has given birth to movies that are a little too sparse, notable examples being Tsai Ming-Liang’s Stray Dogs and Goodbye, Dragon Inn that sit and watch people do very little for extended periods of time- but here Yang furnishes his drama with a weight of importance that drives me to listen and be more attentive during every moment of movement in the story. As a result, what we get is a stunningly rich saga of romance that packs the density and emotion to warrant its exorbitant length; something Lav Diaz and his Norte, the End of History would do well to learn from.

Read More: Best James Bond Movies of All Time

7. Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010)

A great man with an impossible name, Apichatpong Weerasethakul has directed some of the finest films of the past decade in Blissfully Yours and Tropical Malady– both wonderful explorations into his growing sense of style as well as uniquely warm, charming movies that bring across Thai culture in a beautifully personal way. Through watching people and the way they live, as well as how their environment challenges them, Weerasethakul defines the picture of his country as the people in it and the result absorbs like few others can manage. Uncle Boonmee is an original spin on ghost stories that sees spirits return to guide their families, making for some hilarious moments of interaction between normal people and pitch-black demonic ape men with good in their hearts. It’s gorgeous to behold even amidst some of the other flicks on this list and quite possibility the worthiest winner of Cannes’ coveted Palme d’Or this decade. Surely a future classic.

Read More: Best Movie Sequels of All Time

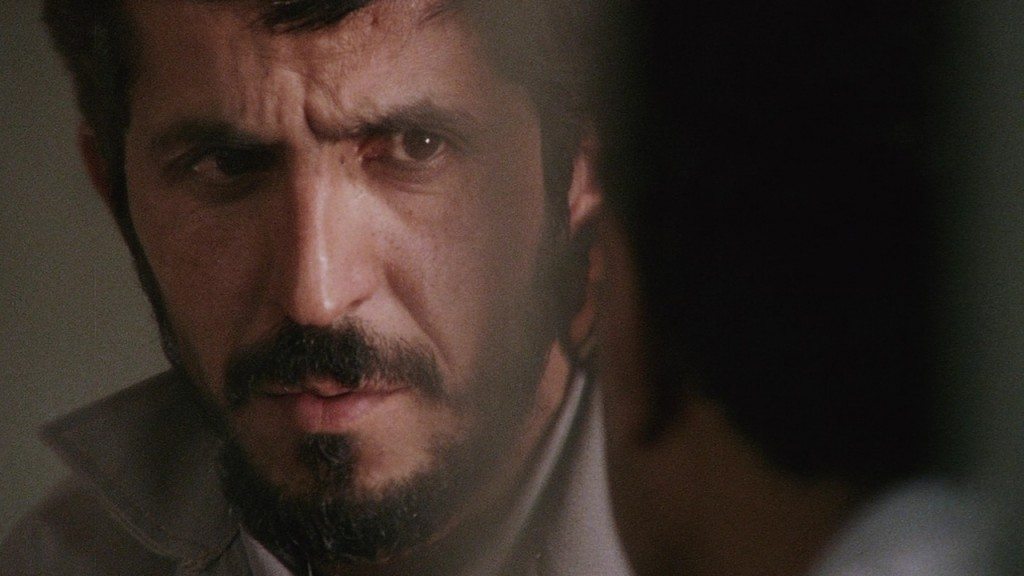

6. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011)

Acclaimed Turkish director Nuri Blige Ceylan is the most recent name to grace this list, his 2014 Palme d’Or winner Winter Sleep also serving as a full embodiment of the term ‘slow cinema’ that I recommend you check out with this one. Nonetheless, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia remains his strongest work in this decade and indeed one of the finest films of the 2010s, with expert direction that sees the tiniest moments that might have been ignored by other directors imparted with a fascinating degree of focus and time. It’s comparatively short in the context of the following movies at just 150 minutes and yet very little happens in this time, the action concealed in brief moments that catch you off guard in their explosive evocation. Ceylan’s piece succeeds best, however, in the immense sense of dread that infects every second of its forward motion. It feels as if something truly nightmarish is lurking in the murky Anatolian foothills the movie inhabits and that, along with an understated but presently authoritative directorial method, is what give the film its gravitational pull.

Read More: Best Superhero Movies of All Time

5. A City of Sadness (1989)

Taiwanese legend Hou Hsiao-Hsien has made an impressive group of absolutely crucial movies, from The Puppetmaster, a Time to Live and a Time to Die, Flowers of Shanghai and the recent The Assassin of 2015- Though none exceed the masterly patience and quiet, skilled practice of 1989’s A City of Sadness. Tracking through the “White Terror” of late 1940s Taiwan, it’s comparable to Ozu on a grand scale with patient family drama evolving into hugely moving moments. The difference comes from Hou’s mind-set and his ability to see the necessity in violence and action to tell a story such as this, his other movies also making clearer use of plot-points to drive the degradation and evolution of his complex, world-weary characters. A City of Sadness is a movie so large that to sum it up here would be both impossible and utterly futile. To live it yourself is recommended instead.

Read More: Best Action Movies of All Time

4. Stalker (1979)

Andrei Tarkovsky’s poetic, meditative, vivid masterwork Stalker is in my opinion the greater film than the next two movies on this list- however Tarkovsky’s place as a slow-cinema master is something I debate and these next two works play with the concept to a far more involved degree than any movie the Russian legend attempted. Stalker does make extensive use of long takes (163 shots in its near 3 hour run-time) and patient pacing however the focus is so keenly invested in the moment that boredom and tedium do not become tools Tarkovsky strives to use, merely regrettable elements of the movie for those people that don’t like it. It’s a shame that not everyone can enjoy Stalker but it does function as a perfect primer for Tarkovsky’s filmography as well as a key piece of 1970’s cinema that manages to create one of the most richly absorbing atmospheric worlds ever set to the silver screen. Simply divine.

Read More: Biggest Box-Office Hits of All Time

3. Jeanne Dielman 23 Quay Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975)

One of the great experimental film-makers, Chantal Akerman let loose in the 1970s with a series of superb films, notably for me 1972’s Hotel Monterey that makes exceptional use of silence and image to create a wordless world of implied terror. Chief among all her cinematic achievements, however, is 1975’s Jeanne Dielman 23 Quay Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles: A movie that explores the daily routine of a single mother over the course of 72 hours. It runs at 225 minutes and in that time provides very little in terms of explicit progression, outside of the various concrete appliances of this very precious time Delphine Seyrig’s Jeanne forces herself through. Instead, this is more a movie you read: Examine in the fine details and absorb the gradual, overwhelming feeling of pressure Akerman so masterfully weaves. The woman was just 25 when she directed this, and sufficed to say it ranks as perhaps the greatest achievement of such a young artist in the history of the medium. Jeanne Dielman is a piece of work I dare not spoil outside of the assurance that it will perplex you, infuriate you, frighten you and put you in a singular perspective like nothing else. Vital.

Read More: Best Movie Villains of All Time

2. Sátántangó (1994)

By all accounts, Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó is indeed the slow cinema movie. It runs at 7 and a half hours, of which just 151 shots transpire with many heading past the 10 to 15 minute mark. Understandably, such statistics put many people off but I think it is important to take them into context. Some people refuse to watch films in monochrome or that run with an essential line of subtitles but are those not just artificialities? Do they matter? Granted, Tarr’s work is famously one of the longest feature films ever made but it is what he achieves in that time which eclipses the investment you make with it. His indelible craft in creating a living, breathing world is the kind of thing comparable to marathon novels like Don Quixote- except here it is realized beautifully on a screen. To stick Sátántangó in is to become part of a place for 450 minutes. To live there, be endeared by its bitter spark of hope and petrified by the lengths people will go to in order to survive. It is the grand apex of cosmic cinema: Filled with gripping moments of existential horror as well as very real scenes of chaos exploding amidst the numbing calm of its more gradual sequences. The resultant work is doubtlessly a difficult one — but again an important stepping stone in the journey of any fan of cinema. Make the commitment.

Read More: Best Time Travel Movies of All Time

1. The Travelling Players (1975)

Another piece that emerged early into the director’s career, Theo Angelopoulos was 40 years old when The Travelling Players was released and poured every ounce of his world-weary experience into the project. The result is cinematic perfection. Bigger, Bolder and Better than even the legion of masterful works that have thus far filled this list — it is far from an exercise in endurance and instead a movie that beckons you into the interior. Angelopoulos makes accommodations for his audience: He slows down after scenes of great importance and reels up to create palpable feeling for things to come. The movie does not directly tell us what is going on in each scene, nor make it clear as to the passage of time and yet each moment is entirely compelling — sewing literally hundreds of microcosmic stories that track human lives with the kind of intimacy, understanding and power nothing I’ve ever seen has matched. There is little more to say other than see it, for this is one of the Great Artistic Achievements of the 20th Century.

Read More: Most Overrated Movies of All Time

You must be logged in to post a comment.