Stop-motion animation in a world of glossy 3-D CGI graphics is nothing short of a statement—about a cinematic journey that prefers a slow, long route and the hand-orchestrated path of puppets, of clay, wood, cloth, over that of the computer. From the Brothers Quay to the Czech school, Tim Burton and Henry Selick, we all have our favourites. Here, is the list of top stop motion animation movies, some classic adaptations and others obscure indies, that make the mind boggle at the possibilities of this technique. You can watch some of these best stop motion animated movies on Netflix, Hulu, or Amazon Prime.

1. Alice (1988; Czech)

Any such list is remiss if it doesn’t begin with this cult favourite. Lewis Carroll’s Alice books are universally regarded as classic children’s stories for grown-ups and have been abridged and edited as children’s literature, spawning animated adaptations (Disney) and quirky transcreations with adult themes (Tim Burton, James Bobin). But Svankmajer’s surrealistic use of stop-motion live action and animation sequences has made a dark fantasy of Carroll’s story that has mostly been interpreted as fairy tale, much to the disappointment of the director, who reads it more as an ‘amoral dream’. Here we have no smooth, animated sequences, but jerky, sped up ones, though the overall effect does have a peculiar fluidity. The effect of watching Alice’s repeated growth and shrinkage is not humorous, but claustrophobic and intimidating by turns. Animals are not cute or willing, but the biting, attacking, threatening kind.

The creatures that populate this Wonderland are irritatingly incomplete, un-whole and crude: a taxidermied White Rabbit made of leaking sawdust, the Mad Hatter is a marionette sipping tea that seeps out of his hollow insides, the March Hare’s button eyes keep popping out and who needs to be wound up, and the unidimensional Card characters. Add drawers that refuse to open by knobs, savouries that spout pins, skeletal animals, sock-puppet caterpillars and a girl being shrunken to a doll and blown up into an effigy, and you have the stuff of real dreams, rather, nightmares, one where ordinary everyday objects come to life. Most effectively, the film uses very little dialogue and what little it does is repetitive and composed of simple lines, with Alice reading out bits of the story. No lush gardens and lakesides, this is the setting of wastelands, dilapidated houses and creepy alleyways. But then, what other dreams does one expect from a blond, blue-eyed girl who whiles away her time by throwing stones into teacups? This is what animation can also be like—unsettling and uncanny. Indeed, commentators have read strong Gothic undercurrents and tropes in the film. Pay attention to her last line in this haunting film. And shudder at its implications!

Read More: Best High School Romance Movies of All Time

2. Mary and Max (2009; Australian)

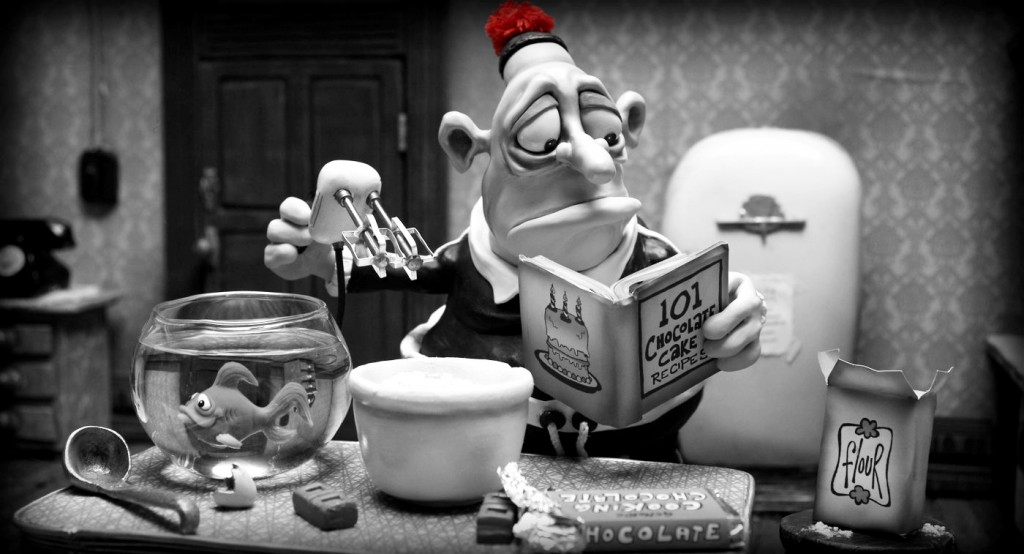

One of my absolute all-time favourites, featuring the very satisfyingly tactile claymation (clay figure animation) technique that is both time-consuming and expensive, is this indie wonder. A story of breathtakingly refreshing friendships among oddballs, the film revolves around mental health—from childhood bullying and low self-esteem, to more adult and debilitating conditions like depression, Asperger’s syndrome, agoraphobia. Mary Daisy Dinkle, a bullied, friendless eight-year-old Australian girl growing up with less-than-ideal parents, becomes pen pals with lonely, obese forty-four-year-old “Aspie” Max Jerry Horowitz in America and what ensues is a decade of exchanging letters, chocolates and bonding over Nobblets, as each finds sustenance in the other’s company and their fortunes change in a world that “confuzzles” them. But this is not an easy friendship, as it requires considerable adjustments, and generates anxieties, disappointment, guilt and forgiveness.

Clumsy and endearing, never was the chunky claymation technique put to better use than this veritable ode to the quirks and imperfections of our flawed humanity, helping us embrace our ‘disabilities’ by forming meaningful relationships along our emotional journeys. The breathtaking details captured by an astonishing array of sets, wobbly puppets and props, conjure a charming world animated with endearingly real people, animals and problems, all presented with liberal doses of humour. An unflinching insight into invisible friends, kleptomania, alcohol addiction, panic attacks, difficult sexualities, broken hearts and suicidal tendencies, it is also a sunny film of laughter, hope and self-love. What better message of hope than when one hears Max say, “You can’t choose your warts, but you can choose your friends”. Elliot has earlier ventured into mental health ‘clayography’ (claymation biography) through his shorts, the Oscar-winning Harvie Krumpet and the shorter trilogy of Uncle, Cousin and Brother.

Read More: Best Vietnam War Movies of All Time

3. The Wanted 18 (2014; Palestinian-Canadian)

This unusual documentary ‘mooovie’ which features interviews, archival footage, cartoon drawings, re-enactments and claymation is about Palestine, Israel and the first Intifada, in a self-confessed cross between Animal Farm and Waltz with Bashir. In 1987, the Palestinian town of Beit Sahour, in support of the uprising against Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza strip, launches a non-violent, civil disobedient resistance to Israel, through the formation of various neighbourhood committees that propose and implement strategies for Palestinian economic self-sufficiency, in aid of its eventual political independence. One such policy is that of buying eighteen cows, hitherto exotic to the area, from a sympathetic kibbutznik, in order to produce milk and begin a small dairy farm. The cows bring a wave of exultant hope and dreams of liberation to the tightly-knit Palestinian community, which finds ingenious ways to revolt and defy the Israeli powers that want to keep them subjugated and dependent, here through the import of milk.

The Israeli military governor, earlier dismissive of the small matter of a handful of cows, quickly grows paranoid about “Intifada milk” and declares that the presence of the cows is “dangerous for the security of the state of Israel”. What follows is an equally hilarious and heartbreaking journey of the ‘wanted’ cows being hidden, transferred, searched for by helicopters and sought out in caves, as the fate of a whole community hangs in the balance even as state leaders meet and agreements are signed. Watch out for the four main cow protagonists who have names of their own and distinct personalities and political opinions. We see a part of the narrative through their wide-eyed bovine wonder at the long and tiresome journeys they undertake, their adventures and misadventures (“We’re dead meat!”) and the dreams and nightmares they inspire.

The animated narrative of the cows allows for the infusing of otherwise painful recollections of memory with generous dollops of humour and by the foregrounding of the cows, sombre, tragic political matters are put in different perspectives—absurd, resilient, creative and above all, very humane. A commentary on non-violent resistance by pacifist ‘lactivists’ is here brought to international light in the absence of coverage by mainstream media by Cowan and Shomali, the latter’s family history being tied to this important historical footnote. Shomali, an artist, animator and filmmaker, who grew up in a Syrian refugee camp with the idea of Palestine as more of a heavenly mindscape than a physical location, says “I believe that a nation that can’t make fun of its own wounds will never be able to heal them.”

Read More: Best Tornado Movies of All Time

4. Rocks in My Pockets (2014; Latvian & American)

Like Mary and Max, this film too delves headlong into a mental health issue—five ‘promising’ women of the director’s family, her grandmother, her three cousins and herself, battle with/ succumb to, chronic depression. This “funny film about depression” begins with a poignant description of Baumane’s grandmother Anna’s botched attempt at suicide decades ago and switches to the director-cum-narrator’s matter-of-fact and outrageously funny advice to the now dead Anna about carrying out a successful suicide. Rocks here serve as tropes and metaphors, invoking the myth of Sisyphus pushing a boulder up a mountain, only to have it rolling back down, as well as rocks that weigh one down into depression and death, literally or figuratively.

Along the way, we are treated to a compressed history of twentieth century Latvia and invited to witness the narratives of five artistically- and intellectually-oriented women, four of whom succumb to their “soothing” dark fantasies of release, unable to cope with their dashed dreams and disappointed hopes. Gene pools and family secrets connect these women together, as they struggle to adjust to motherhood and family life, in their own contexts and times. Anna’s death, a well-guarded and ignored non-mystery, is an obsession that Baumane refuses to let go of, as understanding her grandmother’s story seems to hold the key to her own survival. Each woman is different, with her own demons and angels, and yet each is prey to her biological proclivities and cultural conditioning that threaten to smother her. These women who wanted to be free and independent adults, end up making sacrifices to please the people they love at the expense of their dreams, which to Signe is the real shortcoming they share. But they also share the bond of understanding, as they seem to reach out to each other, beyond death, helping and inspiring each other. One is reminded of the tragic ends of artists like Sylvia Plath and Virginia Woolf, and one marvels at the honesty and integrity that has gone into the making of this film, and the wonderful use of animation in its service (especially the use of visual metaphors).

For instance, the sequence in which Baumane speaks of a bout of depression and suicidal thoughts visualises her as an empty balloon with razor-sharp edges that slash at her insides and Anna is shown flapping around like a slippery fish in her husband’s embrace; characters are shown growing and shrinking in size reflecting their inner turmoil. Ultimately, the film shows how “the road to sanity is a wild drive”, as Baumane walks the fine line between sanity and insanity, working on her life, her work-in-progress, like the artist that she truly is. The animation includes hand-drawn squiggly outlines, papier-mâché masks, stop motion and features foxes, bear-like and alluring alter egos of depression, bunnies (Donnie Darko!) and frogs standing in for human personalities, children transforming into gene strands and a very engaging, animated narration by Baumane herself. Bittersweet and cynically amusing, this one-woman effort that is boldly feminist is a testament to the sophisticated storytelling and powerful communication that animation makes possible.

Read More: Best Horse Racing Movies of All Time

5. My Life as a Zucchini (2016; Swiss)

Animated films for adults are hearteningly becoming the norm, but there are also a few compelling efforts against dumbing down animation for children. Ma Vie de Courgette (dubbed into English as My Life as a Zucchini) is one such film featuring children, which bravely tackles issues that children are usually shielded from. The protagonist is a nine-year-old boy called ‘Zucchini’ by his alcoholic mother who ‘goes away’ in an incident he feels responsible for. He is sent to live in an orphanage where he confronts dark feelings of loneliness, abandonment, being bullied, as well as uplifting ones of friendship and love. His interactions with the other children introduce him to traumatic experiences like sexual abuse, deportation, drug addiction and murder, even as he finds a sense of belonging with this odd, motley group.

The story is ultimately about children struggling to make sense of a grown-up world where “there is no one left to love them” and is heartbreaking and wryly amusing by turns. A rare moment of hilarity ensues when the children try to make sense of adult sexuality. But these children also become resilient and draw strength in their solidarities against manipulative adults and form beautiful bonds with caring, sympathetic ones. Their redemption lies in the finding of unconventional families and the recognition of existence of unconditional love, even if in someone else’s life. With the use of clay puppets, the film capitalises on “the poetic possibilities of animation” and portrays an astonishing range of detail by way of the facial expressions of the characters, especially their huge, limpid eyes, set in heads blown up many times in proportion to the rest of the body and with the help of a range of colours, with varying connotations.

Subtleties like the play of light on the wall, or the very tactility of the shrunken little clay bodies paint a ‘real’ picture and pulls at the heartstrings. This Oscar-winning film is another triumphant feather in the cap of Céline Sciamma, who adapted Gilles Paris’s novel into the screenplay for the film and who has earlier directed marvellous coming-of-age films like Girlhood and Tomboy. Children, whether as characters or as audience, are imagined as the sensitive and intelligent people that they are and a poignant story unfolds in the absence of sentimentality and self-censorship.

Read More: Best Golf Movies of All Time

6. Pied Piper (1986; Czech)

Barta is the second Czech on the list, and this obscure work, “one of Czechoslovakia’s most ambitious animation projects of the 1980s”, a cross between horror and fantasy, too is haunting to say the least. The story is a spooky adaptation of the well-known folk tale of the Pied Piper of Hamelin. Here, however, there is no distinction between the town dwellers and the rats, and children are not made the scapegoats. Technique-wise, Barta makes brilliant use of the wood-carved backgrounds and the carved wooden puppets to evoke both, a medieval gothic setting, as well as to emphasise the decadent coarseness of the Hameliners. Whoever knew wood could be this fluid! Obsessed with minting money, haggling and cheating over it, hoarding it, and using it to buy or coerce sex from women, the men are violent, gluttonous and greedy. The rats, (live ones!) who filch food as much as money and jewels and scurry back into their tunnels, are extensions of the humans, and the humans inversely, the extension of the rats.

In contrast to My Life As a Zuchhini, here the human faces, though distinctive, are foreshortened, so that attire and external accoutrements are emphasised, at the expense of the more empathetic facial features. But in the midst of all this make-believe, some elements are disturbingly real, like the blood sequences, and the wine and meat on the table and at the butcher’s. This makes the violence and the gluttony all the more palpable. The humans with few notable exceptions of the ‘good ones’, speak in inarticulate and guttural grunts, drools and high-pitched gibberish, that only heightens the sense of the ludicrous, and contemptible. The greys and browns of the decaying landscape momentarily get infused with colour once the Piper gets rid of the rats, but soon reverts to status quo as the citizens return to their debauched, morally bankrupt ways. But here, the Piper has more than one reason for seeking revenge. The twist in the ending of the tale is the darkly funny poetic justice we never imagined we could relish in the mainstream version of the story.

The overall impression is a mix of Cubism and early twentieth century expressionist horror films, a triumph in the grotesque and visual excess. Bonus: some sinister flute melody accompanying the Guy Fawkes-like Piper and later, the electronic guitar marking the wrath of the Piper. A veritable collector’s item.

Read More: Best Medieval Movies of All Time

7. Blood Tea and Red String (2006; American)

Possibly the strangest film that I have ever watched, this obscure gem shot on 16 mm is reminiscent of Švankmajer and took more than a decade in the making (Cegavske mentions other influences here). It has been described as “a David Lynchean fever dream on Beatrix Potter terrain”, “patiently surrealist” and “a scruffy rebuttal to the digital suavity and celebrity shenanigans of the Pixar era”. Using words like ‘bizarre’ and ‘macabre’ would be insufficient for this film that unfolds like a poem and has to be experienced rather than understood. It’s excruciatingly slow pace, gothic motifs and inexplicable narrative progression smacks of arthouse sensibilities but lest that sound off-putting, let me rush to add the magic terms, ‘fairy tale’, ‘adult’ and ‘amoral’.

This is ‘Alice’s Rosencratz’, where an Alice-like story is narrated from the point of view of the woodland creatures who literally string her along. Some pointers for those struggling with the narrative framework of the film, can be gleaned from here. It mimics both, the uncanny of a dream and its absorbing array of details that somehow hold together this story through striking sequences like that of aristocratic white mice in Elizabethan attire sipping blood tea, at a card game with blank cards, fondling a lifeless doll they have previously stuffed with an egg. To add to the atmosphere, let me mention plant traps, hallucinogenic berries and spiders spinning red-string webs, hybrid crow-rat creatures, and dolls giving birth. Just when the violent imagery threatens to overwhelm, we see wise frogs and tortoise rides and begin questioning the intentions of the inscrutable, ambiguous characters, and questioning our interpretations. The animation is astounding, both as a nostalgic tribute to older forms of handmade, ‘antique’ stop-motion, as well as the sheer original and imaginative scope of this one-woman effort.

My personal favourites were the use of plastic in the water and fire images, which so effectively capture the tremendously evocative potential of this film. The skilful camerawork and the sparsely haunting music makes up for the lack of dialogues. Symbolism, allegory and social commentary aside ( I am still wrapping my head around those), this take on a children’s pop-up book, is a pure visual-aural feast. One almost feels like a thick-headed intruder in faerie land. Cegavske’s next, the second in this planned trilogy, is expected to be ready by 2022!

Honourable mentions: Not on the list because they are more mainstream favourites that one may have already come across, but impressive nonetheless, are Wes Andersen’s idiosyncratic adaptation of Roald Dahl’s book, Fantastic Mr Fox (2009) and Henry Selick’s terrifying adaptation of Neil Gaiman’s novel, Coraline (2009). Little-known but worthy mentionables are Jirí Trnka’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1959), Jan Balej’s One Night in City (2007) and Saranne Bensusan’s The Hunting of the Snark (2015). While ticking off films from this list, also seek out Mathilda Corkscrew and The Isle of Dogs releasing next year. Happy viewing this holiday season!

Read More: Best Cooking Movies of All Time

You must be logged in to post a comment.