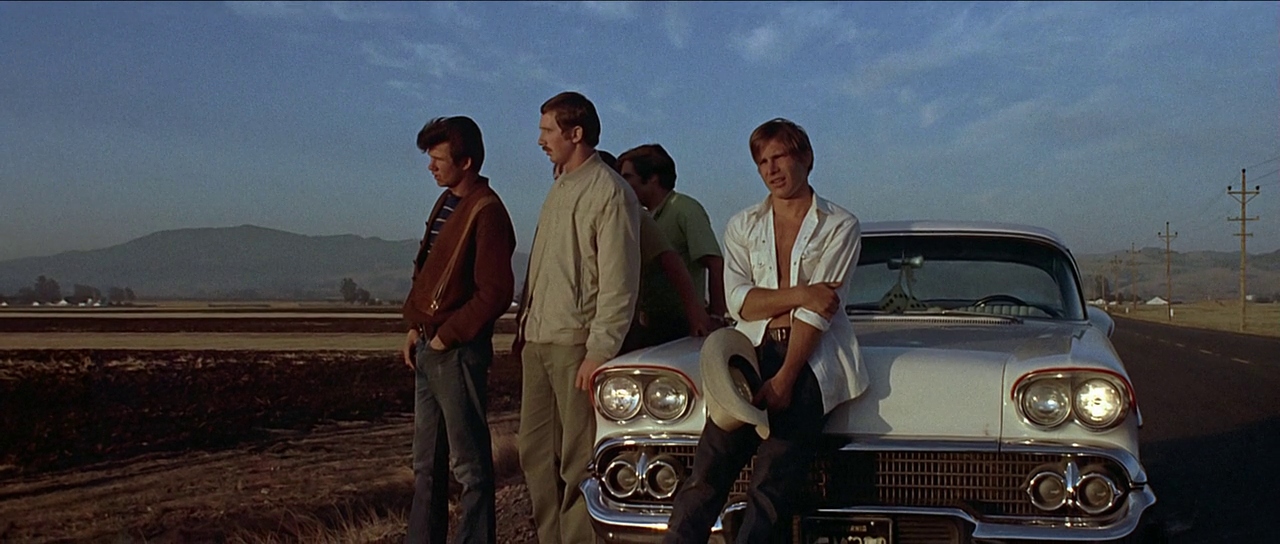

‘American Graffiti’ follows the story of four young men – Steve Bolander, Curt Henderson, Terry “Toad” Fields, and John Milner – that takes place over the course of one night on the streets of Modesto, a small town in the Northern part of California. Steve and Curt have just graduated and are all set to leave for college the next day, so the four friends go out for a night of partying together. But due to one thing or the other, they end up getting somewhat separated for the night, with each of them confronting an aspect of their life that they find daunting.

Directed by George Lucas, the 1972 comedy drama film stars Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, Paul Le Mat, Terry Fields, Candy Clark, Cindy Williams, and Harrison Ford. Set in 1962, ‘American Graffiti’ is a trip down memory lane for anybody who watches it. Everything in the film, from the cars to the way things are done or the way people behave, screams America in the 1960s and would be easily recognizable by somebody who was a teenager at the time. But why is there such a focus on realism in the film? Are there any real-life connections here? If you find yourself asking these questions, then don’t worry, for you are not alone. And we have the answers for you!

George Lucas’ Influence on the Characters

No, ‘American Graffiti’ is not a true story. The film is an original production and was written by George Lucas, Gloria Katz, and Willard Huyck. It is, however, semi-biographical in nature in the sense that the four main characters were inspired by Lucas himself in various stages of his life. In fact, the town of Modesto, where the story is based in, is George Lucas’ hometown. A coming-of-age story, ‘American Graffiti’ was created with the intent to preserve that part of American history in terms of pop culture and music that was popular with George Lucas’s age group at the time.

“I guess the anthropologist side of me never went away and I was very interested in the fact that in the 70s, when I was working in the film industry obviously, we’ve been through the 60s, and the whole innocence of the 50s, the mating rituals of the 50s – a uniquely American mating ritual of meeting the opposite sex in cars was very fascinating to me,” said George Lucas in an interview with the American Film Institute.

The director revealed that during the production of his film ‘THX 1138,’ Francis Ford Coppola (‘The Godfather’) approached him and asked him to make a film that would be “accessible to people.” “I really liked this kind of lost ritual that had gone on in the United States between 1940 and, you know, basically the beginning of the 60s. And I saw the beginning of the 60s as a real transition in the culture, the way – because of the Vietnam War and all the things we were going through – and I wanted to make a movie about it,” Lucas continued.

But while Lucas had the script, no studio was willing to back it up for over two years. The director attributed to the fact that they either couldn’t understand how the story would be told, or did not want to put in as much music as Lucas wanted in the film, amongst other issues. Finally, Universal Pictures agreed to fund the project, but only after Francis Ford Coppola said that he would join the film as a producer.

‘American Graffiti’ is one of the earliest films in history to have wall-to-wall music. It was also one of the factors for studios not wanting to fund the project, partly because it was just not how films were produced at the time and partly because the cost of licensing the music would add up to quite a hefty sum. This tied up quite intrinsically with the cruising culture that George Lucas wanted to depict in the film. ‘American Age’ features 42 different songs, each selected personally by Lucas himself for specific scenes in the film.

In a Making Of video, the famous director spoke about how growing up he used to work as a mechanic in a foreign car service, and said that, “…The cars were very central to me in the movie and the relationship that the people had with the cars, and it sort of got into an area that I was very interested in – still am – and in terms of man’s relationship to the machine and also the intimate nature of people’s familiarity with disc jockeys…”

The radio has always been a big part of the cultural identity of people everywhere, and not just in the United States. It came long before the invention of the television and was effectively part of every household. But more importantly, radio and the disembodied voice of the radio jockeys turned into something of a constant companion for those out on the road, a feeling that Lucas captures in ‘American Graffiti’ through Wolfman Jack. Wolfman Jack was a real-life disc jockey from the 60s to the early 90s whose gravelly voice many of our readers would remember.

The film featured the famous disc jockey as himself, as well. “George knew about Wolfman Jack but I had some relationship with him,” said Coppola in the Making Of video. “I think Wolfman Jack had called me up once or introduced himself, or had tried to reach me for something else, and so I proposed that we get the real guy and George was thrilled that we could have him!”

With a film that is so steeped in American pop culture in the 60s, ‘American Graffiti’ needed a cast that would add to the nostalgia and the overall story. The casting itself was a long and tedious process. Thousands of people were auditioned for the ensemble cast, whittled down and then divided into different groups, screen tests were taken, and every group went through readings upon readings of the screenplay until the main cast was finalized, Lucas disclosed. It was also the first time that videotape had been used during the casting process.

Though not a true story, ‘American Graffiti’ is certainly an accurate window into what America looked like in the early 60s, especially from the perspective of a teenager. The film is a celebration of everything that made the 60s great for so many people, from hot rods to rock and roll. But more than that, it is a vibrant story about everyday people that tells the viewers that you can never know how life would turn out.

Read More: Why American Graffiti is a Masterpiece of Cinema?

You must be logged in to post a comment.