Packing several of the most significant works of art the medium has ever been blessed with, ‘73 stands perhaps above any other year in the 1970s for its rich reaping of cinematic fruit. Honourable mentions go to Badlands, Serpico, World on a Wire, Touki Bouki, F for Fake, The Day of the Jackal, Robin Hood, Save the Tiger and Lone Wolf and Cub. Since Battles Without Honor or Humanity is an ongoing series spanning 3 years, I did not consider it for the list- no matter how exceptional I find it as a whole. With that said, here’s the list of top movies of 1973.

10. The Wicker Man

Robin Hardy’s so sadly overlooked classic of British Horror Cinema has been woefully upstaged by the disastrous 2006 re-make by way of unbelievably bad writing, direction and a bizarre turn from Nicholas Cage- and deserves a prompt and widespread rediscovery. The original Wicker Man’s ominously discordant blend of charming folk aesthetics and eerie Pagan undertones distinguish it as a singularly nuanced piece of film-making, its relentless Medieval score running a lace of discomfort that tightens about the audience throughout until finally tearing in for the kill during the final, petrifying movement in which the flick’s magnetic stranglehold on atmosphere is released in an awe-inspiring wave. Hardy’s meticulous care over the placement of sight and sound never once overwhelms his uniquely unfilled artifice, managing to leave us with a peculiar, absorptive and ravishingly idiosyncratic fantasy fable.

Read More: Best Movies of 2010

9. Don’t Look Now

Nicholas Roeg has never really struck a chord with me, but his devoted study of affliction in Don’t Look Now packs just enough punch to justify the man’s place as an important artist. Performance, Walkabout and The Man Who Fell to Earth all have a hand in forming this gem, cobbled into a mosaic of ideas and images that suffuse his visual language- as well as nabbing elements from all over Horror fiction and cramming them together for a predictably malformed but nonetheless striking fable.

Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie’s infamous love scene expresses the subjugated suffering that occasionally ripples out from underneath the grief-stricken husk of Don’t Look Now, which culminates in a dazzling climax that tears away any and all hope the audience had. Not to say Roeg’s vision is nihilistic, for that is not in his nature: Instead living from moment to moment until eventually landing on a conclusion of all-consuming devastation- rather than framing the story as some pre-destined slide down into doom. This structure makes for a far more compelling and openly optimistic portrait of dealing with loss, an admirable flame of preservance underlying each tick of Sutherland and Christie’s performances. It is their combined convalesce that saves Don’t Look Now from the fate of Roeg’s less substantial work- and the director’s keen attempts to fully consummate the most important scenes that gives it an occasional burst of scorching cinematic power.

Read More: Best Movies of 2004

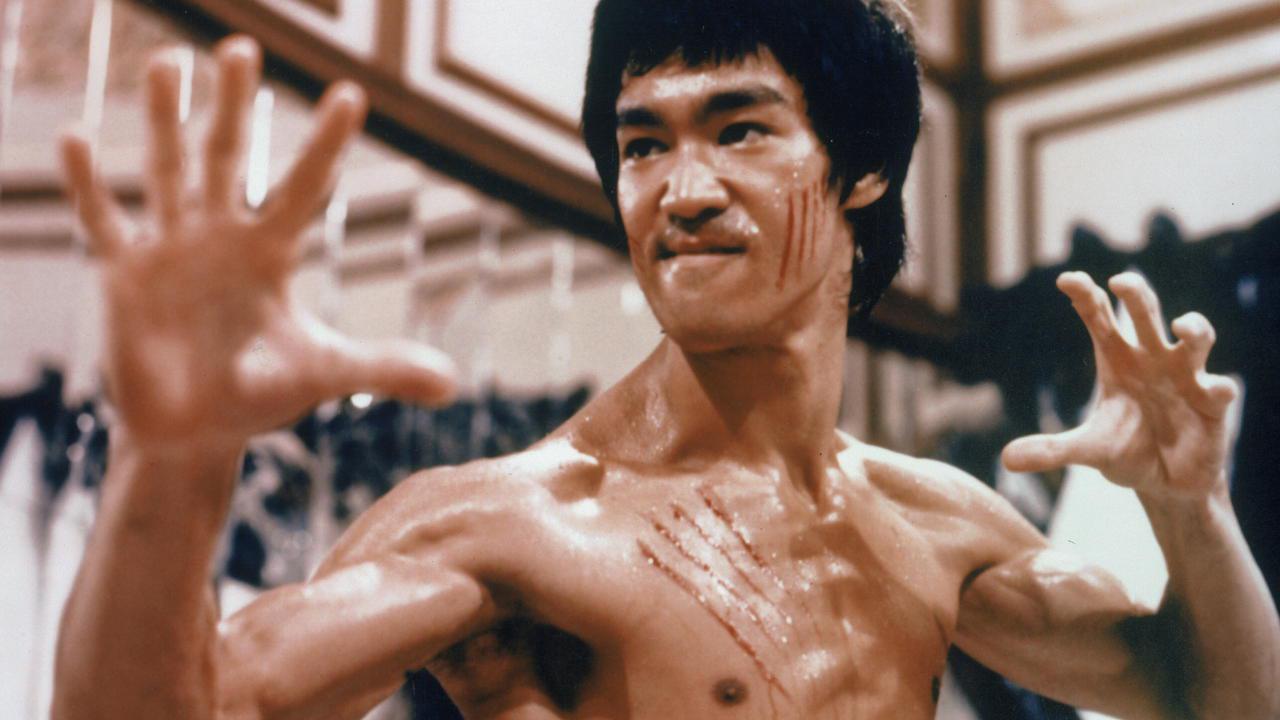

8. Enter the Dragon

Viscerality is key here. Viscerality against all odds. Bruce Lee’s landmark martial arts phenomenon helped pave the way for Kung-Fu cinema in the West and more importantly transcends traditional desire for air-tight plotting and character, shifting the focus onto a performance of the body, rather than the heart within. Lee’s lethality packs every strike with a kinetic shock sure to send the blood rushing through your veins, choreographing scenes he doesn’t participate in just as well as those he trashes together himself- demonstrating a devotion to the quality of picture throughout its runtime.

Enter the Dragon isn’t just peerless entertainment, but an exercise in elevating the medium of cinema in the same way Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia so effectively conveyed the dazzling sportsmanship of its time. Lee’s sharp, brutal fighting style is a testament to his command over the human body and a refreshingly Spartan approach to fight choreography- where under others it has so often spiraled into over-considered tedium as actors lash about at each-other without end. Frank, uncompromising and far-and-away the best of its class.

Read More: Best Movies of 2009

7. Scenes from a Marriage

Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage pulses with a personal touch many of his films manage to evade, escaping their artist in the unbelievable variety of their characters and the precise control with which their tragedies unfold. Unique amidst his filmography then, considering the film is written about his own struggles as a man under the ring, Scenes from a Marriage’s length also dwarves the sub-90 minute run-times of his previous works for a far more expansive affair. Unlike his 312 minute Fanny & Alexander, this film does not quite swim along as sublimely- lagging in places under the strain of its two-character story. Bergman mines the depths of these people’s souls with a grace fitting of his earlier, more accomplished works however- giving us a taste of his own humanity after so skillfully examining the flaws of others for so long. For that and so much more, it is a must-see amidst his already distinguished filmography.

Read More: Best Movies of 2006

6. The Mother & The Whore

Jean Eustache’s monstrous vehicle for the disgorging of his own mind, The Mother & The Whore is a 219 minute marathon of casual conversation, tracking a love triangle between Alexandre, Marie and Veronika through a sickly sheen of monochrome and countless thousands of words shot out at nationalism, individualism, love, lust, sex, sorrow and everything in-between. Eustache’s decadent indulgence and obsession with carnal contact is stereotypically French, and whilst many of the threads The Mother & The Whore take us down are repetitious dry wells of intellectual thought- so too is the vast scope of Eustache’s thought completely compelling throughout. This is a man pouring his mind out onto the screen and whilst it’s rakish, clinically unfeeling amorality is absolutely repugnant that’s part of its charm.

Morbid fascination with the scummy depths to which his characters will sink infect the viewer with a comparably heinous voyeurism as they suckle on the plague-ridden corpse this man has set out on the table. Any artist bearing their soul has to come with any number of alterations: Trimming the fat and shaving off the warts to form a more presentable picture. Eustache’s honesty in disemboweling his own depravity is what makes The Mother & The Whore such a profound piece of work- one any fan of challenging cinema should leap at the criminally microscopic chance to get their hands on a decent copy.

Read More: Best Movies of 1997

5. The Friends of Eddie Coyle

Towering above the rest of his work, director Peter Yates (Bullitt) delivers a remarkably mature and sophisticated take on quotidian criminality running through the streets and suburbs of metropolitan America. The Friends of Eddie Coyle stocks a lens that is both grimy and worn but never once lost in melodrama or over-accentuation: Perfectly comfortable with the delicacy such a subject matter has to be dealt with to strike the right balance.

Treating illegal activity as a day-job without a single spec of shine, Yates paints his world in a hue without a hint of ethical consideration and yet not at all amoral- entirely pragmatic in the character’s pursuit of just getting by. If someone has to get robbed, or kicked about or even wacked, that’s the way things go. No questions asked. It’s this measure of understanding and the richness with which Yates realizes his muddy milieu that elevates The Friends of Eddie Coyle far beyond a run-of-the-mill crime caper into an elegiac look at the days beyond Rome: a washed-out world weary from the troubles of the ’70s and yet still utterly rooted in the conviction that continuation is the only option. It is this blind forward progress which leaves Yates’ picture as enigmatic and fascinating today as it was way back in 1973- and the reason it is so often considered a holy grail amidst the ‘lost’ classics of the 1970s.

Read More: Best Movies of 1995

4. The Holy Mountain

Whereas Alejandro Jodorowsky’s intensely dynamic cinema has oven left me wanting more, perching on the depressing precipice of greatness and so sadly tumbling off into rambling tedium, there are few films this decade- or perhaps ever- than can conjure the same magmatic surge of visual compulsion as The Holy Mountain.

In every scene, Jodorowsky’s magical myriad of creative depths are plundered for their riches and splayed up upon the screen with a vivacity to transfix even the most sober of cinema-goers. His images come alive in their admirable ignorance towards reality in favor of sewing their own fantastical dreamland, subverting our expectations of art-galleries, factories and fascistic states to set a whole new spin on everything we know. An intoxicating experience that musters a satisfying climax that is so rare in this brand of film-making, The Holy Mountain is quite simply seminal. See it.

Read More: Best Movies of 1991

3. Spirit of the Beehive

Víctor Erice’s luminous Spirit of the Beehive is one of the most bewildering films ever made. His equally magical 1983 follow-up El Sur serves up just as special a piece of cinema, however very little the medium has ever been blessed with can match the worldly ataraxy of the man’s enchanting debut. Erice’s restrained style holds a perfect six degrees of separation between camera and subject, inviting us into an entirely believable cinematic language which observes exactly the same way we do: Just as speechless and dumbfounded by the film’s most infinite moments as any member of the audience might be. It leads us back down the path of youth and then into something more, something even children can’t quite grasp in their endless inquisivity.

Víctor Erice seems to take on the entire world at once in Spirit of the Beehive– creeping to the very edge of all its magic and mystery in one breath-taking step that entrances, overwhelms and ultimately leaves us without any answers. Maybe there aren’t any out there? Regardless, I’d happy take a trip into this man’s vision of post-Franco Spain day after day in the hopes of watching these people torn between two worlds finally find their own.

Read More: Best Movies of 1992

2. The Exorcist

I speak no hyperbole when I say William Friedkin’s The Exorcist is perfectly directed. Nothing is out of place. What’s more, it achieves a profundity of power that has rightly elevated it amidst the ranks of the Greatest Horror films ever made. I think it’s even more than that. Friedkin’s film is a superlative piece of drama that just happens to be about demonic possession: It’s terrifying because of the weight its characters and their situation holds- developed impeccably through William Peter Blatty’s exceptional story that so expressively struggles between rationalism and faith. Its characters are constantly scared- unsure of their place in the universe and teetering on the edge of losing themselves; but also filled with compassion and a burning desire for companionship, perhaps in some attempt to help fix themselves.

This pervading world of self-doubt is perfectly adapted from Blatty’s book, rooted in Friedkin’s rigorous cinematic method: Each scene progressing with the director’s characteristic confidence and stark impact that so fastidiously fastens itself to the later scenes, every moment imbued with an incandescent supernatural anger as Merrin and Karras fight as if they’re fighting for the fate of the entire world. Now and forever, a cinematic legend.

Read More: Best Movies of 1985

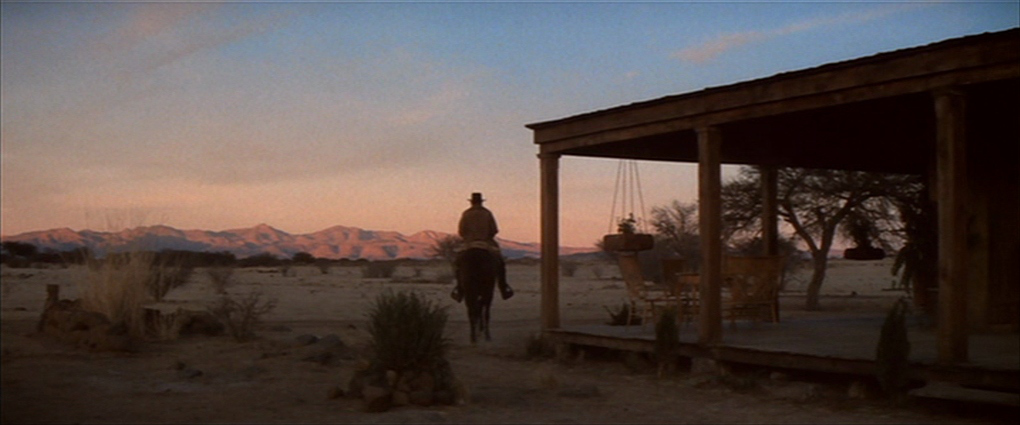

1. Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid

The story of Sam Peckinpah mirrors the bitter anguish that permeates his body of work: A reflection of the rage and frustration he dealt with both in his personal life and in facing with Hollywood executives who throttled his vision and left him struggling for artistic power in the twilight of his career. As a point of study, Peckinpah’s violent, explosive and substance-scarred personality in attacking creative repression is far more fascinating to me than that of Orson Welles, who got on with film-making at whatever capacity he could scrape together with the same smug smiling hubris as always. I bring this up only because it offers an intriguing comparison between the apparently perfect Hollywood film, Citizen Kane, and elegiac melancholy of inevitable doom that makes Pat Garret & Billy the Kid one of the most profound films ever made about the American mythos. Peckinpah does not any moment express a desire to impress: Even his famously impassioned gun-battles are salted with a nest of sharp shingles that blunt any triumph or catharsis one might have drawn from his earlier work.

The director’s time under the baking sun of controversy after The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs developed a bitter spark that softened into something special with Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid– a film which embraces the inevitability of death and ignores the legend of its emblematic heroes in favor of a far more mature, realistic and ultimately moving observation of our mortality. It had confidence in the vulnerability of hanging onto the brink of the long black silence, desperate to share another couple of seconds with a cast of characters who could die as quickly as they entered the story- and it is this dangerous concoction of resolute sentimentality and grim rationalism that make it such an endearing piece of work.

Hal Hartley’s Surviving Desire preaches that “the trouble with us American is that we always want a tragedy with a happy ending” and that infinitely apt line highlights the chief success of Pat Garrett: Its refusal to conform. It never commits to an extremity of emotion, coasting the line between the joyful ambiance of just being alive and the crushing silence of coming face to face with death. It eludes the classical Hollywood formula without a beat and in doing so creates as important a film as has ever been made in America- because it confronts the truth of terminality under the guise of legend. Something to learn from. Aspire to. Be a part of its world every chance you get- because flicks with this kind of comprehension not only of their own completeness, but of their place in the cinema of their nation, are seldom seen.

Read More: Best Movies of 1998

You must be logged in to post a comment.