The American Dream, the life. It has been a working ideal for a whole generation of people across the world that have spent entire lifetimes chasing that ever-elusive dream. There have been people who have achieved it, and as with any other opportunistic paradigm, there have been people who haven’t, and there are people who are still trying. Then again, where there is prosperity or more particularly, the illusion of it, there is going to be resistance, and what better medium to express that than through the most accessible of art forms, Cinema?

The 90s films, especially, saw the deconstruction and the shattering of the fake glass façade that was the great American dream after decades of glorification. To sum it up, the idea overarching this is the refusal of the illusory, the materialistic and a recognition of the embrace of mundanity in the modern age, something that was our trade-off for said materialism. In my opinion, no two popular movies portray said themes in a better manner than David Fincher’s ‘Fight Club’, based on the eponymous novel by Chuck Palahnuik, and our talk of this evening, ‘American Psycho’, by Mary Harron, based on the eponymous novel by Bret Easton Ellis.

The very soul of both movies, sauced up with unbridled chaos is essentially the same, although the mode of conveying the same may be different. Where ‘Fight Club’ relies on hardcore commentary from an outsider, ‘American Psycho’ takes the route of a resilient, silent kind of understated satire, often wrapped up as even comic moments in an otherwise dark film, from the insider point of view of someone who is knee-deep into the business, and the chasing of that dream.

Needless to say, both of the films also deal with a repressed psyche and have climaxes that lead to the unmasking of that psyche. Now that we have set the groundwork for the very climax that we are going to discuss in detail, this is where we temporarily part ways with ‘Fight Club’ and delve headfirst into the complex thought web that is ‘American Psycho’. But first, a brief reminiscing of its head-scratcher ending. Read on.

The Ending, Explained

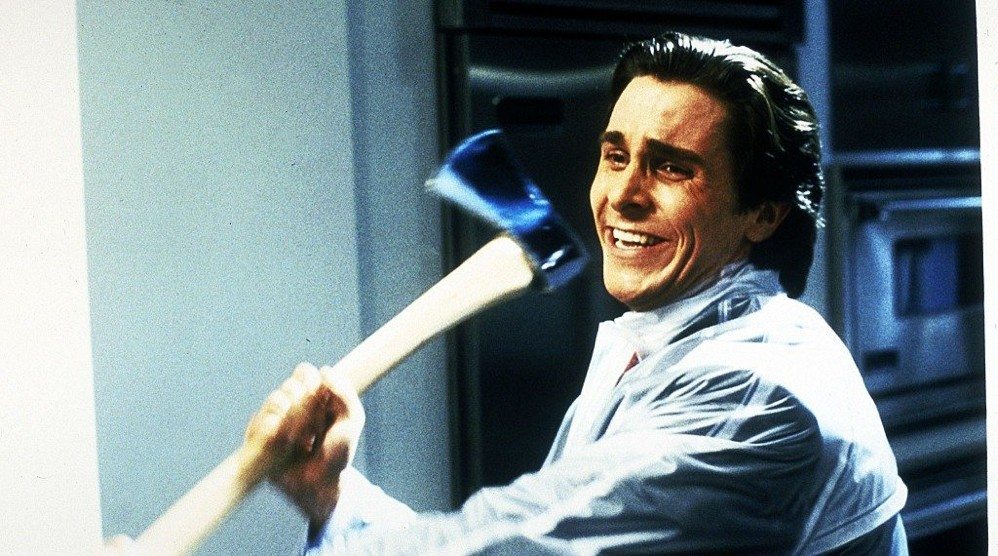

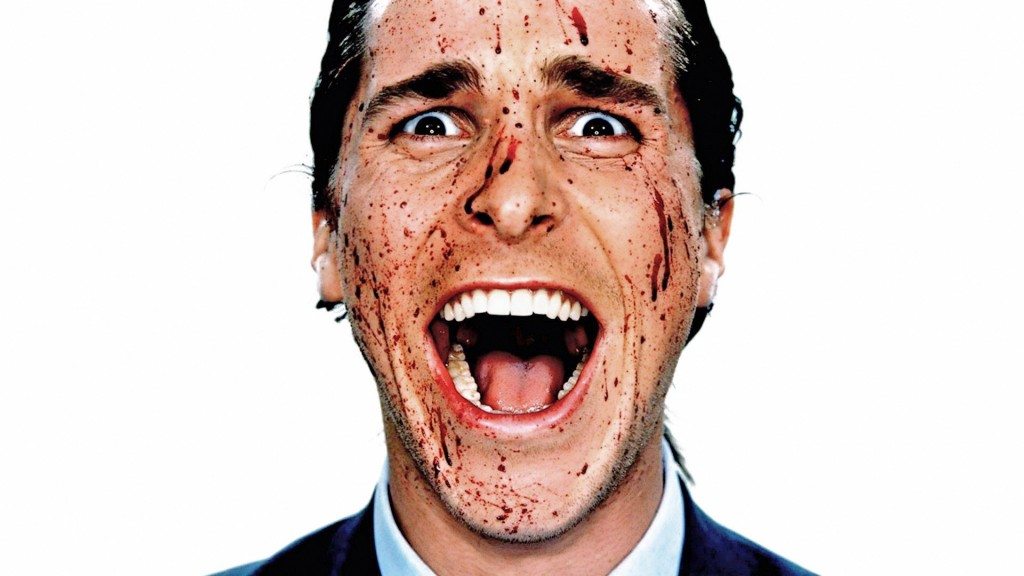

What I consider the ending of ‘American Psycho’ is the point in the film when our unlikely protagonist’s world starts falling apart, quite literally, and like in Nolan’s ‘Inception’, the highly fragile “dream” world that Patrick Bateman (played by a devilishly feisty Christian Bale) built begins collapsing. Before you might begin to draw any ideas from the comparison I just made, I will begin to quickly expand upon that.

Yes, the ending has been ever questioned and debated upon by the entire fandom of this movie and the book, to this date, and that is what I believe is the beauty of it. The internet too is rife with explanations and theories, and after a brief mum period, even the makers came out with their own intentions. However, as I stated, the dark beauty of this is what you can take from it personally, and irrespective of the numerous theories out there, here is what I took away from the film. Well, If something inspires dialogue even two decades hence, it is in all possibility worth discussing. Straight to the ending now.

The “collapse” begins almost right after Patrick Bateman dumps his fiancé Evelyn (Reese Witherspoon) and goes back to “return some videotapes”. Later that night, while withdrawing cash from an ATM, the absurdities start when the ATM mysteriously displays a message asking Bateman to feed it a stray cat. Now stay with me, since I would want you to spot the oddity or absurdity in every line hereon, something that is so far removed from reality that it doesn’t make the slightest sense. A cat mysteriously appears right in front of him, who he intends to shoot, stopped only by an onlooking woman with Bateman ending up shooting her instead. He is immediately pursued by cops in patrolling vehicles, and in a faceoff in an alley with them, he shoots and kills them too, with the shootout ending after the cars explode when Bateman fires at them.

For a second there, you see even Bateman looking at his gun in disbelief before escaping from there. In an attempt at fleeing to his office, he mistakenly enters a completely identical office building, something which I believe is a satirical, Jacques Tati’s ‘Playtime’esque jab on the repetitive architecture of modern office spaces, killing a janitor and a security guard in the haste of exiting there. He then enters another office he believes to be his, exactly identical, and frantically makes a call to his lawyer, confessing to the murders he committed in explicit detail, after he feels that a police helicopter is chasing him down, and a searchlight falls on the window of his office that he seemingly evades. It might be worth noting that the helicopter is never actually shown in the particular scene.

During the call however, yet again peculiarly, he is not able to put a pin on the number of people he killed during his rage fiascos, quickly oscillating between wild guesses ranging from 5 to 10, to even 20 and 40. The frantic events of the night come to an abrupt halt just as they conspired, as if the manhunt for somebody who shot down atleast five people in the street was miraculously called off, and we jump to the events of the next day wherein Bateman still believes that the events of last night conspired in exact absolution as shown in the film.

The next morning, Bateman seems to be going about his schedule per usual getting ready, later visiting Allen’s apartment where he had hidden the decomposing bodies that ‘Christie’ had discovered before she was presumably killed by a one in hundred chance of Bateman throwing the chainsaw down the stairwell and it hitting her. To his surprise, he is taken aback when he finds that the apartment is up for sale, and that the interiors are all remarkably white.

The bodies are gone, and contrary to his expectations of seeing the cops or the authorities down there, he finds a realtor tending to potential customers about the flat, who then confronts Bateman and tells him that a Paul Allen never lived here. He begins to spiral out of control just as he makes a very frantic and nervous phone call to his assistant, Jean, one of the handful who survived their fate at Patrick’s hand when she was earlier about to be murdered by a nail gun by him. A suspicious Jean then walks into Bateman’s office, only to open his diary and be terrified of extremely graphic, brutal, and sadistic drawings of the people, and in particular the women he had killed.

Meanwhile, back at Harry’s Bar where he’d told his lawyer Harold Carnes he’d be that afternoon, he and his colleagues are still arguing over where to get reservations for the evening. Seeing Carnes, he immediately confronts him asking about the message of his confession he left on Carnes’ voicemail. Carnes recognises the message but laughingly dismisses it as a prank, addressing him as Davis, and terms his prank’s giveaway to be “Davis” trying to frame “Bateman” for the murders since he was “such a dork” and a “boring, spineless lightweight.”

When Bateman confronts him further, impatiently so, confessing in the first person to the murder of Paul Allen, Carnes is shook but still doesn’t believe him, stating that he had dinner with Allen just a few days ago in London. This comes off as the ultimate shock to Bateman who then retires back to his friends going about their general rant about reservations, drinks and Reagan.

Bateman blankly stares into the distance while having a double scotch and delivers his now famous closing monologue in voiceover. “There are no more barriers to cross. All I have in common with the uncontrollable and the insane, the vicious and the evil, all the mayhem I have caused and my utter indifference toward it, I have now surpassed. My pain is constant and sharp and I do not hope for a better world for anyone. I fact I want my pain to be inflicted on others. I want no escape. But even after admitting this, there is no catharsis. I gain no deeper knowledge about myself, no new knowledge can be extracted from my telling. This confession has meant nothing.” Now, now. We have a whole lot of explaining to do for the events that conspired. Head on to the next section for that.

I Simply Am Not There!

Coming back to the comparisons with ‘Fight Club’, I am going to drive this discussion in the direction of the big revelation in the finale for both of the films. ‘Fight Club’ makes it pretty clear that Tyler Durden was an idea: a dissociative identity created by the narrator as a refuge, a sort of counter-play to the worldly submissive personality that he was. He was never real, and the narrator manifested Durden’s personality in the image of who he wanted to be, deep beneath.

Now carry all of that hypothesis over to the ending of ‘American Psycho’, and apply all of what I just said to Patrick Bateman’s case. Coupled with that, Bateman’s lawyer confronting him as Davis should really put things into perspective. That would be, if you are not already swayed by the argument made by an ambiguous subplot within the film, implying that nobody in the white collar world actually recognised anybody by their real name, where Bateman can be Halberstram or Hamilton or Davis, McDermott can be Baxter, and Paul Allen can be Reed Robinson.

It is a sharp comment on the homogenous nature of the very clothing these men wear, the very talk they talk and the walk they walk; even their visiting cards that were essentially designed to be the same, but ended up being pawns in a game of one-upmanship. All of them look and sound almost exactly the same, something that is wonderfully covered and conveyed in one sweeping shot during Patrick’s final confession in voiceover before the film closes. However, as far as I am concerned, there is something much deeper, much more complex at play than simply mistaken identities. Consider this piece of dialogue from the beginning of the film as we are just introduced to the character of Patrick Bateman.

“There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me. Only an entity, something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze, and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours, and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable, I simply am not there.”

Now, I can completely guarantee that replacing Patrick Bateman in the above lines with Tyler Durden would still make the lines work. In fact, they would work even if you were to use, say, Norman Bates, or even Kevin Wendall Crumb in place of Bateman. You get the idea: however, it is more than a case of even a dissociative identity. It is one of a psyche repressed by the pressures of “fitting in”, so much so that the repression, and the desires that yields become murderous.

Here, I want you to keep an open mind and consider that Patrick Bateman might actually be someone else, and the unreliable narrator, “Davis” subsumes the identity of Patrick Bateman to lead his sadistic acts to fruition, just as “Bateman” assumed “Halberstram”’s identity when killing Allen, or “Allen”’s himself while inviting the prostitutes over to his home. Peculiarly so, he even names the prostitutes according to his own liking.

It is like a sadistic puppeteer with all the strings in his hands: the dramatic equivalent of the shedding of masks our unreliable narrator had to don all through the day, pretending to be someone he was not. In that, everything that conspired in the film being narrated by “Patrick Bateman” might actually be just a figment of his imagination, a further extension of his murderous psyche. That the only murders and acts of violent sadism that conspired were on the pages of Bateman’s diary, something that an unassuming Jean has to witness, might not be such an implausible theory after all.

To sum it up, think of it as the story of a faceless guy named Davis, something that would blend in all too well with the wall street guys. There is also a Patrick Bateman, who in Harold Carnes’ eyes might be a dork, but someone who certainly appealed to Davis. He manifests a personality of Bateman: suave, stylish, and narcissistic, one that he uses as a face to unleash his murderous desires at night. More than half of what transpires (or even all of it) might just have been figments of his ripe imagination to say the least: a repressed psyche finding its way out through whatever means.

Sound too outlandish? We also have an alternate theory, one that is more widely accepted among the loyal fandom.

I’ve Got To Return Some Videotapes?

The theory I presented above is a completely personal one; most likely, you would not find one on the internet that would agree with the one above, so here is the more conventional take, one that most people seem to agree with anyway. This one would state that Bateman was Bateman, and that he did commit some of those murders, firmly ruling out Allen’s, Christie’s and the ones towards the end, all remarkably being instances that sit on the subtle fine line dividing the “only marginally possible” and the “utterly ridiculous, something which just goes on to further the hypothesis of his psychopathy.

That the diary with the graphic descriptions is real, and some of those murders that I listed above only conspired in his head further weighs in on his condition. However, no one really can predict whether his condition was actually the result of his high pressure, phoney work environment and the pressures of conformity in the elitist circle he found himself a part of, but the film doesn’t fail in making satirical comments about it, making sure the viewer goes home with so much more.

The Director’s Take

In the two decades that have since passed, literally millions of theories have flooded the internet about the ending of the film, especially the ambiguity of it all. Now, there is a marked difference in what the book intended, what the director intended, and what the film presented, that has actually left behind a huge lack of clarity, but therein lies the beauty of it. As a result, to date, there exists no singular definition or “meaning” per se of the ending, as I have said before. It has meant differently to different people, and it continues to do so.

Needless to say, what I state here is my personal take on the ending and what I took home from it, despite the director, Mary Harron clearly stating otherwise in an earlier interview. “One thing I think is a failure on my part is people keep coming out of the film thinking that it’s all a dream, and I never intended that. All I wanted was to be ambiguous in the way that the book was. I think it’s a failure of mine in the final scene because I just got the emphasis wrong. I should have left it more open ended. It makes it look like it was all in his head, and as far as I’m concerned, it’s not.”

A Confession Without A Catharsis

I consider the psychological constructs and the degree of truth in the finale of the film to be like an antique radio. To each listener (or viewer) trying to tune on to the same frequency, it will settle at a different point for when he/she hears it perfectly clearly. Coming back to the film, this much is for certain that Bateman didn’t commit all of those murders (considering that you go with the second theory ruling out him committing any), and especially not Paul Allen’s and all the people in the end.

It is also certain that Bateman was a lowkey psychopath, hiding under the guise of an everyman, succumbing to the pressures of acceptance. In fact, more than the acceptance, it is the drive to stand out from a superficial, homogenized society that drives most of the actions here, and you, sir, sit on a throne of lies if you claim that drive hasn’t gotten to you. The hide, made of Valentino suits and Olivers’ glasses, strutting about in high rising offices proves to be so inconspicuous that in the world Bateman operated, anybody could be anybody.

That in fact is the pining and towering achievement of ‘American Psycho’s finale, certainly more than the ambiguity of it. As Davis, as Patrick Bateman or as a simple nobody, a confession about the cold-blooded murder of at least forty people, true or not, actually meant nothing. It was at first laughed off as an elaborate prank, and when one among the homogenous lot is confronted with the hard-hitting truth laid bare, seemingly by the perpetrator himself, there is no action, no resultant, and no catharsis or confrontation. Even if Bateman might not have committed any murders until then in the film, all the while the desire to kill being amply clear from his graphic diary, this would be the exact moment that would have birthed a monster, the American Psycho. “This is not an exit”, as the sign on the door behind Bateman in the closing scene says.

Read More: Shutter Island, Explained

You must be logged in to post a comment.