Well, you might not find them as entertaining as thrillers action movies, or comedies; you might not even be inclined to watch them during lazy weekends while voraciously searching for cinematic kicks. Notwithstanding, philosophical movies do exist, and there are valid reasons to believe that they exist for the good. Just in case you have a deep penchant for comprehending the governing dynamics of human existence or if you want to take some time out to dig into your own life, or if spirituality interests you more than temporality, philosophical movies might just be the right thing for you. Strictly speaking, there is no singular definition of what a philosophical movie is.

However, most philosophical movies involve the quest for a suitable meaning of life and adopt definite stands on existentialism. Some of them harp on the unpleasant realities of life while some others make subtle attempts at deciphering the interrelationship between the natural world and the supernatural world. Whatever might be the ingrained theme, a movie with philosophical elements compels you to think and contemplate on a multitude of issues concerning both the material entity and the ethereal entity.

While mainstream commercial cinema seldom made forays into the metaphysical world, there have been renowned art filmmakers from all across the globe who have constantly dabbled in the genre. So, we tried our hands at collating the ten best philosophical movies of all time, extremely strenuous and difficult as it might have been. It is important to appreciate that all the movies mentioned here, all of whose ingrained theme is philosophical, might be classified under other larger genres as well including but not limited to drama, science fiction and comedy. Without any further ado, let us take a look at the list of top philosophical movies ever. You might be able to watch some of these best philosophical movies on Netflix, Hulu or Amazon Prime. Which of these movies with philosophical themes do you like the most? The list includes deep philosophical movies, philosophical comedy movies and sci-fi philosophical movies.

20. The Rat-trap (1982)

From one of the finest auteurs Indian cinema has to offer comes ‘The Rat-trap’, a film that is more or less a character study on the outside (like most of Adoor Gopalakrishnan‘s cinema), though upon further inspection, it seems to me at least, to be a satire on the construction of the modern society. Telling the tale of a middle-aged man who lives with his two younger sisters, the film describes him as someone who is frightened of his surroundings and who’d rather depend on his sisters than do the work himself.

With an investigation of what he’s afraid of and what comes off of it, ‘The Rat-trap’ attempts to mirror a captured rodent to a man living by the system prescribed by the society around him. What does shutting oneself within one’s house do for the world around them? Should we act for the benefit of this ‘outside world’? What is the point of it all? I also feel there’s a cautionary side to the story presented here about how society demands you to follow its ways, failing to do which would make you as insignificant as a rat in a trap. The troubling question then is, what if you’re the one who is right?

19. The Adversary (1970)

The pivotal concerns of Indian neorealism in cinema are usually handled in succession: first, there is the background of poverty, which gives way to the eruption of jealousy and fear, ultimately resulting in the incentive to perform a radical action, mostly in the form of a revolt. ‘The Adversary,’ possibly the best entry in Satyajit Ray‘s ‘Calcutta Trilogy,’ handles its plot likewise but accentuates its themes and morals with a character who is brilliantly analyzed. The entire film is based on his world-view; his perception of people and events is what spurts the subtle emotional core.

The film flows beautifully and tells its story with a touch of intimacy, utilizing dream sequences and external visual elements to get deep into and understand the thought process of our leading man. I’ve always enjoyed Ray’s handling of the lower middle class, but it is here that I feel he reaches a point that can be considered his philosophical best, with an ending that is as personal as it is effective, closing the chapter it opened halfway with somber poetry, captured with the career-best visual eye of cinematographer Subrata Mitra.

18. The Spirit of the Beehive (1973)

If you look for information on this film online, chances are you’ll stumble upon the Franco dictatorship period, something that this Spanish film is said to be opposing, albeit subtly. While some of this is definitely interesting, and I really can’t deny any of the connections made, I find this film to have a deeper layer to itself, not merely being held within the shackles of politics.

The “spirit” in the title refers to the drive that moves bees to search for and store honey as ordered by the queen bee, which this picture paints over with the human emotion of desire, touching on the personal, secretive ones within each of the family members forming the protagonists of this film, clearly signifying the change in interests they have brought on by several factors like age, occupation, romantic affiliations, etc. Seen through the eyes of a little girl named Ana, ‘The Spirit of the Beehive’ shows the change a hint of fear brings into her life following a viewing of ‘Frankenstein’ (1931) on the big screen, drastically affecting her impressionable “desires”, and moving the tale into a softly surreal, symbolic direction.

17. The Beautiful Troublemaker (1991)

How many times have you looked in the mirror and, seeing your reflection glaring back at you, thought it had a deeper meaning? The work of nature given an interpretation is the work of an artist. A painting is what the painter sees. And if he is good, his work is true, it is pure. It may not please anyone else, but it satisfies him. And that’s all that matters. ‘La Bella Noiseuse’ tells the story of an old artist who, after a 10-year hiatus, decides to paint the masterpiece he let go of once again, with the assistance of an unwilling model. The strains and bitterness of collaboration between a painter and his model are wonderfully investigated. The beauty of a professional partnership is how the relationship gets smoother over time. This is the case in this film.

The model begins to understand her artist, she sees what he sees in her, as she stands nude in various strenuous poses. He sees her soul, her bones, rather than the outside. As he extracts what he desires from her—with some brilliant acting, I must say—there is no longer any sexual tension between the two. There never was, in fact. Empathy is in the air as the two slowly dive into each other’s lives. There are little touches of magic throughout the picture, but what grips my mind now are those final few minutes of this grand experience, which ties it up and makes the film even more meaningful.

16. Ikiru (1952)

I had attended a funeral immediately after seeing this film recently, one that was quite popular because the deceased was a local politician, and one that grew awfully uncomfortable because of the poor maintenance of the house in which he was residing. I remember I had counted up to 13 cats that this 73-year-old unmarried man shared his abode with – them and his unmarried sister, who is now all alone. For a brief period at his place, all I could think of was this film, especially when people began to discuss the filthiness of his house rather than all the things he had done for the community.

Life is all about what you think it is, and the meaning that your experiences and emotions give it, and ‘Ikiru’ bases its themes on this very statement. The film is about a man on the quest for life within his life, which was for a long period, spent in a dreary, dull fashion. It asks the age-old question about what it means to truly live, and save for a couple moments of overdramatic storytelling, this film manages to tell a humble, painful little tale about a man who knows he hasn’t much time left, and it’s as beautiful as it is effective. That song at the end is very disturbing to hear.

15. Ship of Theseus (2012)

It takes a special sort of talent to make an audience feel for a character they never see. Or maybe they do, in parts, but never as a whole. ‘Ship of Theseus’ is a film that experiments upon the philosophy of its title, utilizing three characters in three different scenarios to tell a deep, interwoven tale about artistic expression, personal beliefs, and morality. The film goes about complex paths to tell its simple stories, the first of which follows a blind woman who happens to be a respected photographer, while the second has to do with a monk who has a severe condition of liver cirrhosis, and the third is about a stockbroker in the aftermath of an operation whereby he receives a kidney that may have been stolen.

The Ship of Theseus philosophy is studied intricately as all three protagonists sense a certain loss in their respective environments as a result of the transplant, in a way that they’re still the same person, in form, but different in ideology.’ ‘Ship of Theseus’ should be seen more as the presentation of an idea (or a plethora of ideas) than a film following the conventional elements of cinema, and in that, it has been executed quite well.

14. Dekalog (1989)

Krzysztof Kieslowski’s magnum opus (and that’s really saying something), in my opinion, is ‘The Decalogue’ (or ‘Dekalog’), which was released in 1989 in the form of a mini-series consisting of ten episodes, each of which attempts to delve into the philosophical truth in The Ten Commandments, dissecting one per episode. A couple of favorites of mine are Dekalog 7, which concerns itself with the Commandment “Thou shalt not steal” using familial connections to give a new interpretation to the word steal here; Dekalog 3 which uses “Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy” to talk about a strange Christmas story wherein a man leaves his family to ride around with his ex-girlfriend, on the eve of the 25th; Dekalog 6 which uses “Thou shalt not commit adultery” to communicate a story involving a young man’s affection for a women many years older than him; etc.

Kieslowski’s honesty to the craft, his exceptional understanding of human nature, and his beautiful writing skills, etc. make ‘Dekalog’ the effective masterpiece it is, growing into a work of art that sticks with you, that makes you think about life, religion, modernization, love, and the meaning to it all.

13. A Ghost Story (2017)

Films surrounding the topics of death and morality have always gotten to me, because when done well, they’re able to frighten, since they are able to stimulate thought. ‘A Ghost Story’ deals with the “life” of a man after his passing, where he begins to observe a warped sense of time and space, moving through which gives him (or so we assume, since we do not see his face nor do we hear him speak) a more thorough understanding of existence, not just of mankind but of the very world itself.

This is perhaps the only film I’ve seen that explores the beauty of the end, and the best part is that it isn’t just restrained to that. ‘A Ghost Story’ touches beautifully upon the intimate topics of loneliness, boredom, and ennui. The score is as mesmerizing as the cinematography, and the presentation is emotionally charged to an almost colossal extent that it left me grieving because, with the ending that gives you little to hold on to, the film interprets a lifespan as ultimately amounting to nothing, which is a sad thought.

12. Mirror (1975)

Andrei Tarkovsky‘s highly personal masterpiece is one that transcends the film genre. The emotions delivered by the film are wholly based on the viewer’s perception of it, which is part of the distinctive artistic quality of the great film. Personally, I see it as an account of a man’s life – a man who could very well be Tarkovsky’s attempt at a caricature of himself – his memories and his present melding with each other to create this elevated sense of poetic fusion, which isn’t to be completely made sense of, since the film puts forth the motion that the brief little moments that occur in human life are ultimately only as good as the memories that are created out of them, and continues to show how these memories affect the individual remembering them in the phase of existence that they are living through at a given point.

Though this isn’t a very happy idea to communicate, Tarkovsky’s film also sets to argue that moments becoming memories doesn’t necessarily have to be looked at as a bad thing, because rather than the experience of a single moment as it happened, the thinker is left with a bunch of those recollections, acting as a summary to his life, however faint they may be. A brilliant look at childhood and loss, ‘Mirror’ is one Tarkovsky feature that I do not attempt to make further sense of.

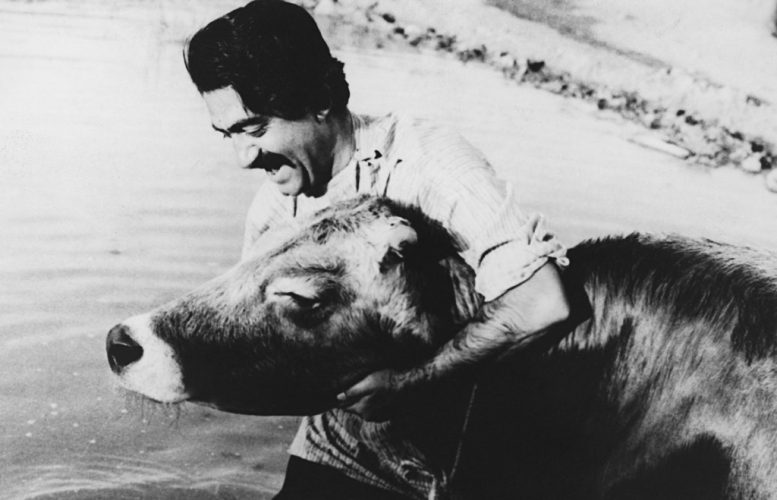

11. The Cow (1969)

Having experienced it myself, I know that having to lose a very close friend is one of the hardest things one goes through in life. Informing someone that their close friend has passed is, perhaps, just as hard, and this is the basic plot of ‘The Cow,’ one of my favorite Iranian films of all time. A cow, belonging to a middle-aged villager, dies while he is out of his village. The other residents in the locality try their best not to disclose this fact to him when he returns, knowing the bond he’d shared with the mute domestic animal.

‘The Cow’ is about more than what its basic themes communicate, though. The characters who form the villagers of the film present a lifestyle controlled by an ideology bogged down by the beliefs and customs of their times. After the cow is dead, for example, people are afraid to dispose of the body because of the beliefs they hold close to their hearts. Traditional Iranian music backgrounds this stunning character-driven film that ends with a Bergman-esque existential thought relating to the identity of a person and the elements that help define it.

10. 8½ (1963)

Considered to be a major avant-garde feat, Federico Fellini’s Italian classic ‘8½’ is a trip down the fantasies and imagination of a confused filmmaker. Roughly autobiographical in nature, the movie is a comedic take on the tribulations that befall the protagonist while trying to make a science fiction movie. It portrays recurrent motifs and deals with deep philosophical dilemmas. The film could also be considered to be a metaphor for the quintessential artistic struggle in the face of an overtly dry and arid modernization process. The film bagged a couple of Academy Awards in 1964 – one for the Best Foreign Language Film and the other for the Best Costume Design (black-and-white).

Read More: Best Movie Lines of All Time

9. Solaris (1972)

One of the most unique achievements of global cinema, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Russian masterpiece ‘Solaris’ is a calm and contemplative movie that strives to comprehend the significance of human subsistence. Principally harping on the concept of identity and self-discovery, the movie chronicles the story of a psychologist who goes on a trip to the space in order to find out what happened to the crew of a spaceship, who seem to have gone crazy. A rather complex narrative, ‘Solaris’ received the coveted Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival in 1972.

Read More: Best Character Driven Movies of All Time

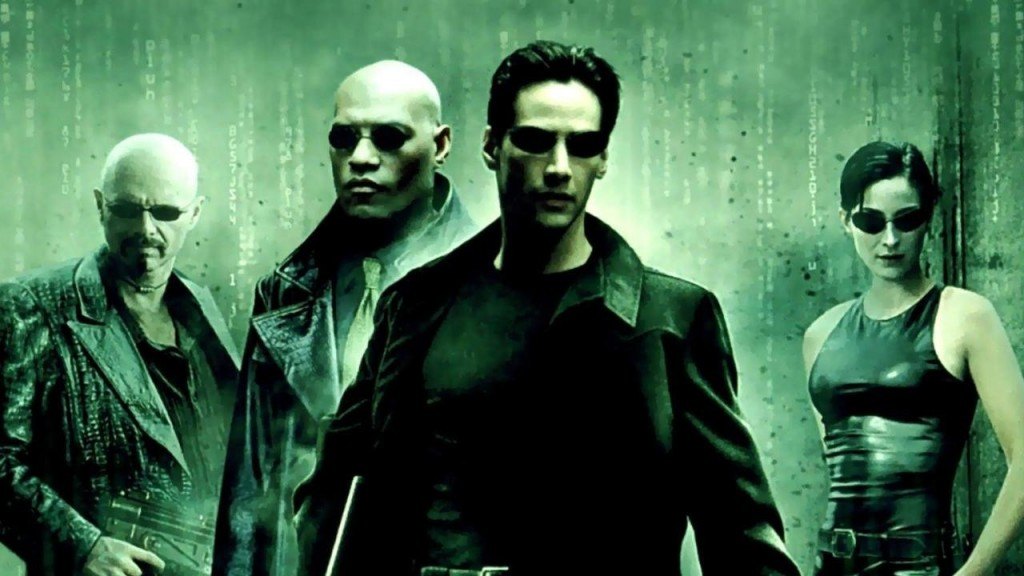

8. The Matrix (1999)

Way more than just a movie, ‘The Matrix’ has been nothing short of a phenomenon. It changed the way people looked at the world around them and even turned them cynical. Directed by the Wachowskis, the American-Australian movie could very well be described as a living nightmare. A film that virtually introduced the rather terrifying concept of simulated reality, it asked a number of vital philosophical questions about humanity and its actual purpose. A person who has watched the movie will never be the same again. The movie clinched four Academy Awards in 2000 in the categories of Best Film Editing, Best Sound, Best Sound Effects Editing and Best Visual Effects.

Read More: Best Zombie Movies of All Time

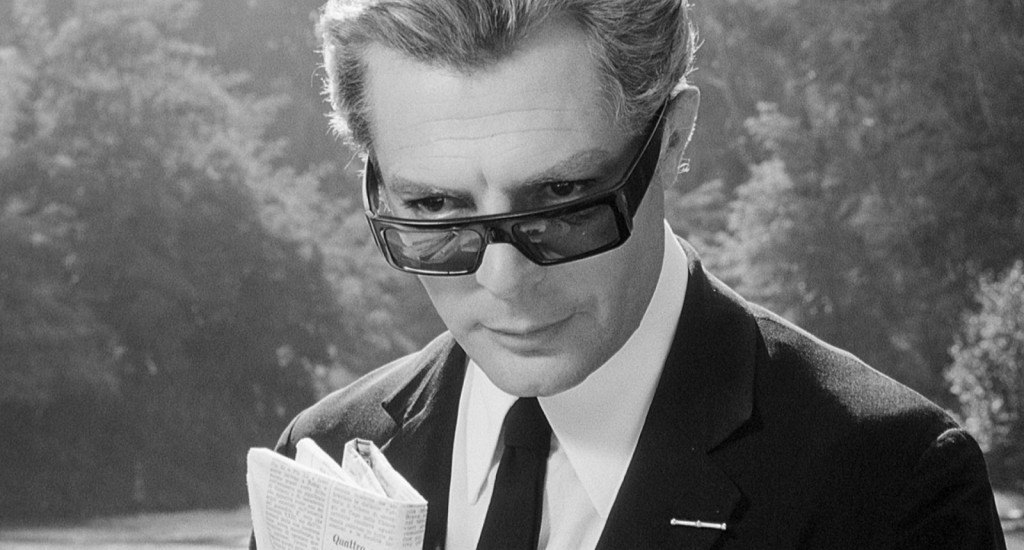

7. Alphaville (1965)

Considered to be a pioneering piece of work from the stables of Jean-Luc Godard, one of the pillars of the revered French New Wave, ‘Alphaville’ is a haunting tale of a secret agent who goes to a distant city in space in pursuit of another secret agent. The film mixes both noir and science fiction elements. A movie that essentially captures the eternal battle between humanity and technological mechanization, ‘Alphaville’ has been consistently ranked as one of the best movies in the history of cinema. The film was awarded the prestigious Golden Bear award at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1965.

Read More: Best Movies Based on Books

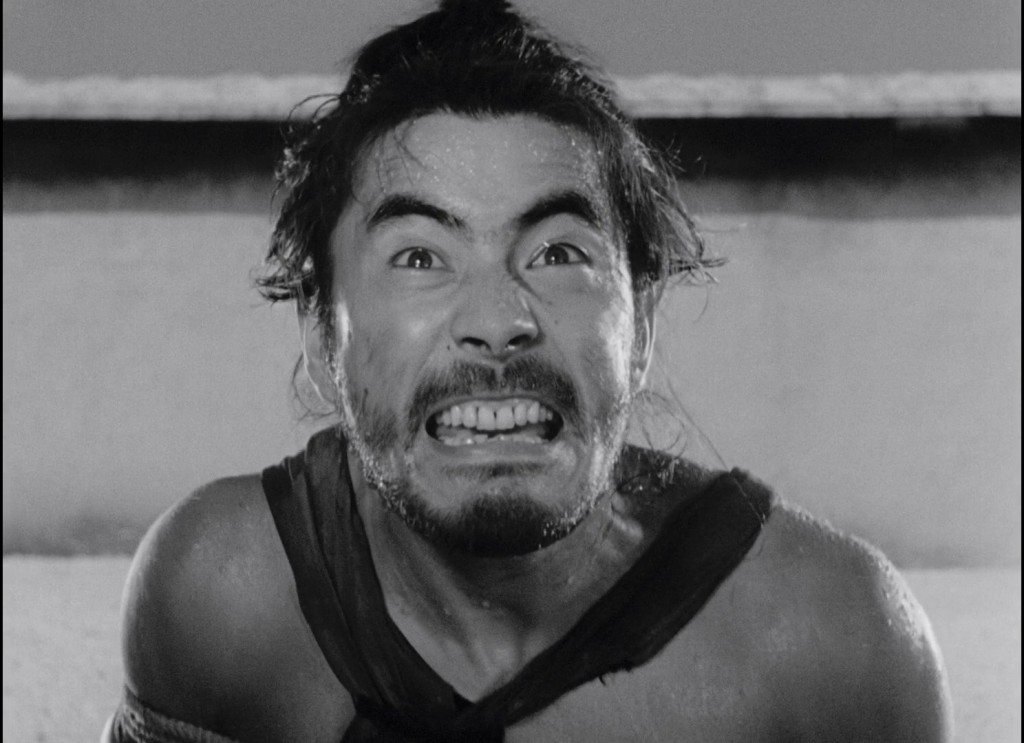

6. Rashômon (1950)

A cinematic milestone in all its dimensions, Akira Kurosawa’s jidaigeki Japanese classic ‘Rashomon’ is a voyage into the dark corridors of the human mind. It harps on the multiplicity of perspectives and presents multiple and contrasting explanations for the same criminal episode involving the rape of a woman and the murder of her husband. The movie, now deemed to be amongst the best of all time, firmly established Kurosawa on the global circuit. Numerous scholars have labelled the film as an allegorical representation of the subjectivity of truth and the futility of adopting an absolutist view of life. The film managed to claim numerous prestigious awards, including the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951 and an Honorary Academy Award in 1952.

Read More: Best Anthology Movies

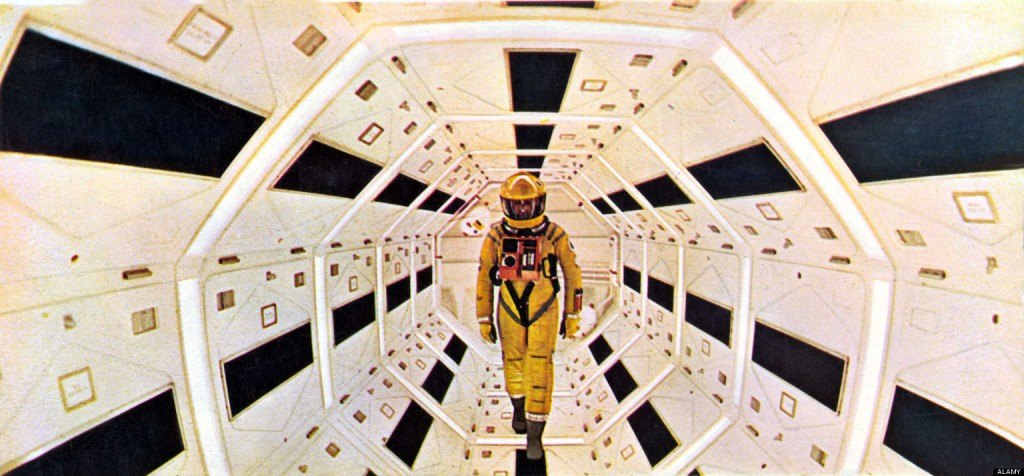

5. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Undoubtedly the most authoritarian piece of work directed by the maverick filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ could aptly be described as a crazy rendezvous with mayhem and uncertainty. With themes ranging from existentialism to evolution, the British movie has acquired a cult status over the years. Inspired by a short story named ‘The Sentinel’ written by Arthur C. Clarke, who co-scripted the screenplay along with Kubrick; the movie chronicles the journey of a crew of scientists to Jupiter along with the sentient computer HAL 9000. The movie went on to become one of the biggest influences on future science fiction projects and is considered to be a philosopher’s delight. The movie landed Kubrick with the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects.

Read More: Best Narrative Movies of All Time

4. The Tree of Life (2011)

Rightly cited as one of the ten greatest movies of all time by renowned film critic Roger Ebert, Terrence Malick’s American venture ‘The Tree of Life’ tries to comprehend the meaning and purpose of life in way that is both unique and effective. Punctuated by scenes of vivid childhood memories and the origin of life on earth, the movie has the potential to change the way a person perceives his/her life. It straight away divided the critics into two distinct segments. One group lauded the movie for its thematic richness and the other despised it. It bagged the coveted Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011 and has been listed by BBC as one of the 100 greatest American films ever made.

Read More: Best Comic Book Movies of All Time

3. Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003)

Billed as the best piece of work from the stables of South Korean auteur Kim Ki-duk, ‘Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring’ is a story that narrates the life of a Buddhist monk as he passes through the different stages of life. The film can be considered to be a metaphor for the perpetual continuity and cyclical nature of human life. Along the way, it also explores the themes of love, sacrifice, devotion, seclusion and fidelity. Known for featuring very few dialogues, the movie is deeply contemplative in nature and takes the audience along on a serene trip.

Read More: Best Road Trip Movies of All Time

2. The Seventh Seal (1957)

Having been ranked as the eighth-greatest film of world cinema by the revered Empire magazine in 2010, Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman’s ‘The Seventh Seal’ could be described as the metaphorical meeting with death. A dark fantasy film that portrays a game of chess between a medieval knight and the human incarnation of death during the Black Death in Europe, it tries to uncover the answers to a lot of existential and philosophical questions pertaining to life, death and the presence of God. The film, which has become a cult classic over the past six decades, strongly established Bergman as one of the pillars of world cinema.

Read More: Best R-Rated Movies of All Time

1. Stalker (1979)

Somewhat inspired by the novel ‘Roadside Picnic’, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Russian film ‘Stalker’ tells the story of a person who guides two other persons to a place known as the Zone, rumored to possess the ability to fulfill the ‘innermost’ desire of any person. The movie is a strong foray into the conscious and subconscious compartments of the human psyche. The film is also symbolic of the universal human quest for hope, peace and order. A metaphorical voyage into the subtle intricacies of the human mind, the film was ranked 29 on the British Film Institute’s 50 Greatest Films of All Time poll. Subsequent reviews by critics worldwide have consistently ranked ‘Stalker’ as one of the finest creations of global cinema.

Read More: Best Black Comedy Movies

You must be logged in to post a comment.